An Analysis of the Generic Pharmaceutical Industries in Brazil and

advertisement

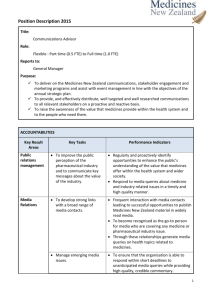

An Analysis of the Generic Pharmaceutical Industries in Brazil and China in the Context of TRIPS and HIV/AIDS By Sasha Kontic Introduction Recently, a paradigm shift has occurred in international public health with respect to the treatment of HIV/AIDS infected people living in developing countries. Previously, many policy makers and academics had assumed that people living with HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, would never be able to access liveextending pharmaceuticals because treatment was neither cost-effective nor feasible. Prevention of new infections was the only option. Unfortunately, prevention efforts have had limited effect. This old thinking is being replaced by a new recognition of the need to provide people living with HIV/AIDS with anti-retroviral medicines (ARV medicines). This new objective is exemplified by the World Health Organization’s “3 by 5” initiative to supply three million people living with HIV/AIDS in developing and middle income countries with ARV medications by the end of 2005.1 Several factors have led to this change is thinking, such as: widespread political awareness of the rapid increase in the rate of new infections worldwide, especially in Africa, Asia, and Eastern Europe, the availability of substantial amounts of humanitarian funding from governments, organizations and private charities to obtain AIDS medicines and look for AIDS vaccines, the advent of lower priced generic antiretrovirals due to competition among manufacturers in countries such as India, and the disappointing results of over two decades of AIDS prevention education in these most affected regions.2 Furthermore, widespread consensus now exists that antiretroviral medicines should be available to everyone who needs them as a matter of human rights. Treatment is urgently needed for those individuals infected with the HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa, where 25 million people were estimated to have been infected by the end of 2003. 3 HIV/AIDS is now classified as a pandemic in sub-Saharan Africa, and yet less than ten percent of people who need treatment have access to it.4 A significant barrier to access to treatment is the exorbitant price of antiretroviral medicines (ARV). All ARV medicines are currently under patent protection in developed countries, and only beginning in 2006 will the twenty years of patent protection expire for the three medicines that were developed first.5 However, less expensive generic versions of some 1 World Health Organization, The 3 by 5 Initiative Homepage, Online: http://www.who.int/3by5/en/ Markus Nolff, “Paragraph 6 of the Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health and the Decision of the WTO Regarding its Implementation: An “Expeditious Solution?” (2004) 86 J. Pat. & Trademark Off. Soc’y 291 at 305 3 UNAIDS, “2004 Report on the global AIDS epidemic: 4 th global report” at 30. Online: http://www.unaids.org/bangkok2004/GAR2004_pdf/UNAIDSGlobalReport2004_en.pdf 2004 Update available online at: http://www.unaids.org/wad2004/report.html (reports median number of those infected increased to 25.4 million) 4 WHO, “Progress Report for 3x5: Executive Summary” at 7. Online: http://www.who.int/3by5/en/execsummary.pdf 5 The three drugs are Didanosine (ddI), Zalcitabine (D4T) and Zidovudine (AZT). Please see: P. Boulet, J. Perriens, F. Renaud-Théry / Joint UNAIDS/WHO publication, “Patent Situation of HIV/AIDS-related 2 of the patented ARV medicines are being produced legally, as a result of differences in the domestic intellectual property schemes that existed in some countries prior to 1995.6 Brazil, China and India are developing countries with extensive domestic pharmaceutical manufacturing capacity that are eligible to produce a select variety of ARV medicines in generic form. In particular, the generic industry in India has had a major impact on reducing the cost of ARV medicines; however, India’s ability to supply generic medicines will be impeded because the Indian government has harmonized its patent legislation with international standards imposed by the World Trade Organization to take effect in March 2005. Although Indian companies will continue to be able to produce several of the ARV medicines that they manufactured before the legislative changes, and will remain a major exporter of generic drugs, other sources of inexpensive generics are required. In this paper, I will provide an overview of the pharmaceutical industry in two candidate developing countries - Brazil and China – and I will offer insight into how these countries can assist with the supply of affordable medicines to people living with HIV/AIDS in developing countries. These two countries were selected because of their population sizes, levels of economic development, domestic HIV/AIDS problems, and existing generic pharmaceutical industries. All three factors affect the price of pharmaceuticals, as the large demand for the ARV medicines and the lower production costs in developing economies allow generic manufacturers to sell at low prices and still make a profit. Yet despite Brazil and China’s promise to become important exporters of ARV medicines, neither country has realized its potential as India has. In order to understand the situation in both countries, sections II and III of this paper will provide case studies of the generic pharmaceutical industries in each country in the context of international intellectual property rules and domestic policies for managing HIV/AIDS. The case studies will focus on three major areas: 1) the capacity and development of the pharmaceutical industry in each respective country, identifying the number of generic manufacturers, the quality of drugs produced and the level of supply available to the domestic market; 2) the patent status of ARV medicines in each country, including the history of amendments to Brazilian and Chinese patent laws; and 3) the ability of each country to export patented ARV medicines under compulsory licenses. This topic is of particular importance because as treatment continues for drugs in 80 countries (2000). Online: http://www.who.int/medicines/library/par/hivrelateddocs/patenTShivdrugs.pdf; Also see Pascale Boulet, Christopher Garrison and Ellen ‘t Hoen, “Drug Patents Under the Spotlight – sharing practical knowledge about pharmaceutical patents” Medecins Sans Frontieres, May 2003. See Annex A – Patent Table. Online: http://www.aerzte-ohne-grenzen.de/_media/1256__msf 6 In 1995 the World Trade Organization (the WTO) was established, and all members of the WTO were required to harmonize their domestic patent laws. However, as will be explained in Section I, not all WTO members amended their patent legislation at the same time, resulting in the situation where some drugs patented in developed countries were not eligible for patent protection in certain developing countries. HIV/AIDS patients, the primary first-line medicines that are easiest to produce generically lose their efficacy.7 Many of the second and third line medicines were discovered later than the first-line treatments and will remain under patent protection for several years in developed as well as developing countries. As will be discussed next in Section I, a generic manufacturer may be granted the right to copy a patented drug through a compulsory license. Although generic companies in both developed and developing countries can be granted the ability to copy second-line drugs through compulsory licensing, it is more economical to produce them in developing countries where a domestic demand for the drugs already exists. Section I – TRIPS and a Changing of the Guard in the Generic Industry Despite political will, financial aid and lower drug prices, there are still many obstacles to accomplishing the “3 by 5” initiative in sub-Saharan Africa. One of the greatest challenges in providing access to AIDS medicines arises from international intellectual property rights and obligations imposed on the member countries of the World Trade Organization (the WTO).8 Upon becoming WTO members, all countries are obliged to amend their patent legislation to comply with the Agreement on TradeRelated Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (the TRIPS Agreement), and introduce patent legislation, if no such legislation existed beforehand. The rationale behind the TRIPS Agreement is to standardize domestic intellectual property regimes in order to establish minimum standards in the area of intellectual property. Article 27(1) of the TRIPS Agreement mandates that all member states make patent protection “available for any inventions, whether products or processes, in all fields of technology, provided that they are new, involve an inventive step and are capable of industrial application.” An important consequence of Article 27(1) is that all WTO members must ensure that their pharmaceutical products are recognized as patentable inventions.9 This provision is problematic for developing countries, because (aside from the generic industry in India), the pharmaceutical industry is dominated by a small number of countries and companies that market patented drugs at monopolistic prices, unaffordable to most people in low-income countries.10 Please see the following reference for more information about ARV Treatment. WHO, “Scaling up Antiretroviral Therapy in Resource-Limited Settings: Treatment Guidelines for A Public Health Approach” (2003 Revision). Online: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/en/arvrevision2003en.pdf 8 The WTO was established in 1995 and is the successor of the multilateral trade system under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). In order to promote and regulate the liberalization of international trade, all signatories to the WTO must observe the multilateral agreements comprising the WTO Convention. 9 The TRIPS Agreement also standardized the length of protection for pharmaceuticals to be twenty years 10 WHO, “The World Medicines Situation” (2004) Ch.1 at 3. Online: http://www.who.int/medicines/organization/par/World_Medicines_Situation.pdf 7 Prior to the enactment of the TRIPS Agreement, most developing countries did not provide patent protection for pharmaceuticals. Excluding pharmaceuticals from patent protection allowed developing countries with pharmaceutical industries to manufacture generic versions of high cost drugs (patented in developed countries) at a lower and more affordable cost. Developing countries without pharmaceutical industries also benefited because they could legally import the lower-cost generic drugs at competitive prices.11 Developing countries with generic pharmaceutical capacity that did not recognize pharmaceutical and product patents12 prior to the TRIPS Agreement include Brazil, China and India. Of the three, India has developed the most successful generic drug industry, and extensive domestic competition within India has been a major cause of the lowering in price of many pharmaceuticals including ARV medicines. Although India only exports 20% of its generic products, the quantity is significant as India provides roughly 67% of the pharmaceuticals purchased by developing countries.13 However, Indian patent legislation finally became TRIPS compliant on January 1, 2005, and the impact that this will have on the production of affordable medicines is unknown. It is important to note why India only just amended its patent legislation in 2005, and was able to continue to promote generic production of patented drugs after becoming a signatory of the WTO Convention. After the TRIPS Agreement came into force on January 1, 1995, countries were granted different time frames for compliance based on economic and financial reasons. Article 65 dictated that all developed members had one year (1996, if membership began in 1995) to amend their patent legislation whereas developing members had five years (until 2000) to become TRIPS compliant. However, special provision was made under Article 66.1 of the TRIPS Agreement for countries like Brazil and India, which did not recognize product patents, to have ten years (until 2005) to implement a TRIPS compliant patent system.14 Both Brazil and China implemented a patent system recognizing product patents earlier than India,15 which led to a situation whereby India was only one of a few countries that could legally produce generic versions of drugs patented after 1995. However, India eventually was going to have to standardize its patent legislation, and in anticipation of the new system a special mailbox system was implemented to accept applications for products patented during the interim years between 1995 and 2005. India opened the mailbox on January 1, 2005 and its patent office must now review 8,926 patent applications16 that want durational patents for medicines and medical devices. Fortunately, in the case of HIV/AIDS medications, all of the first-line treatment drugs were patented prior to 1995 and therefore the TRIPS Hoi Yan Pang, “Implementation of Compulsory Licensing Provisions Under TRIPS in China” (LLM, University of Toronto, 2003) [unpublished]. 12 The advantage of a process patent system is that any small change in the steps used to create a drug allows a generic producer to sidestep the patent. The goal is for several manufacturers to produce the same drug by using different methods, thereby stimulating competition and lowering drug prices. 13 Supra note 11 at Ch. 3, p. 24 14 The period under Article 66.1 was extended until 2016 for least developed countries at the Doha Conference in November 2001. 15 I will explain the implications of early compliance with TRIPS in the case-studies of each country 16 HIV Treatment Bulletin, Volume 6 Number 4 April 2005. Online: http://www.i-base.info/htb/v6/htb64/Patent.html 11 Agreement will not impact the generic production of these drugs in India.17 However, as demand for AIDS drugs patented after 1995 increases, natural price controls arising from generic competition in India will no longer exist. Although Indian, Brazilian and Chinese generic companies are prohibited from unrestricted production of patented medicines, access to less expensive generic versions of patented ARV medicines can technically be accomplished. The TRIPS Agreement does not allow generic competition during the life of a patent, but is amenable to countries waiving pharmaceutical patent exclusivity rights for public health emergencies. In special circumstances, a country may issue compulsory licences in accordance with the procedure outlined in Article 31 of the TRIPS Agreement.18 Article 8 states that countries may “adopt measures necessary to protect public health and nutrition and to promote the public interest in sectors of vital importance to their socio-economic and technological development, provided that such measures are consistent with the provision of this Agreement.” At the Fourth WTO Ministerial Conference in Doha, Qatar, November 9-14, 2001, the Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health (the Doha Declaration) was enacted, which clarified the meaning of article 8, stating that the TRIPS Agreement should not prevent a WTO member from taking measures to protect public health (paragraph 4) and that member countries may decide what constitutes a public health emergency (paragraph 5(c)).19 However, the provisions of Doha Declaration were not useful for developing countries without pharmaceutical production capacity, because Article 31(f) of the TRIPS Agreement authorizes a compulsory license predominantly for supply of the domestic market of a manufacturing country. Therefore, the TRIPS Agreement was further amended by a decision made by the WTO on August 30, 2003 (August 30th Agreement)20. Paragraph 2 of the August 30th Agreement enabled countries with development capability to waive their obligations to manufacture only for domestic purposes under Article 31(f) and export generic pharmaceuticals produced under compulsory license. However, the requirements for issuing a compulsory license to export medications are quite difficult for importing countries to meet.21 For example, an importing country must assess its generic industry's capacity to produce the medicine 17 Supra note 6 (patent charts). However, generic production of second-line drugs such as Ritonavir (1992), Lopinavir+Ritonavir (1995) and Nelfinavir (1993) may be granted patent protection if the mailbox system accepts applications for drugs that have pre-1995 filing dates but were not marketed prior to 1995. Indian generic companies that were producing these drugs under the former patent regime may be able to continue doing so, subject to undetermined (and probably expensive) licensing fees. 18 A compulsory license is a mechanism through which the national government of a Member state can grant a third party permission to manufacture for domestic purpose a drug which is currently under patent protection. 19 WTO Ministerial Conference. Fourth Session. Doha, 9-14 November 2001. WT/MIN(01)/DEC/2, November 20, 2001. 20 The Decision of the WTO is titled Implementation of paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, and is set out in WTO document WT/L/540. Paragraph 6 of the Doha Declaration recommended that provisions be made to allow export of patented pharmaceuticals via compulsory licensing to countries without pharmaceutical manufacturing capability. 21 John S. James, “WTO Accepts Rules Limiting Medicine Exports to Poor Countries” AIDS Treatment News, September 12, 2003. Online: www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0HSW/is_394/ai_108394861 locally, and if capacity is insufficient, it must then notify the WTO of its decision to import and explain and justify its decision. Next, the importing country must notify a potential exporter, and that exporter must in turn seek a voluntary license from the patentee. Failing that, the exporter then seeks a compulsory license from its own government on a single-country basis. In addition to demanding technical requirements, compulsory licenses pose a particularly vexing problem by making it difficult to establish a continuous market for a generic drug. This is because any given drug can only be produced in quantities specified by short-term orders. Thus, in most case, it is not economically viable for a generic manufacturer to incur the time and expense needed to produce a drug that may be supplied infrequently or to only one purchaser.22 However, compulsory licensing can work, especially where exporting countries are also producing the drug for domestic demand under an existing license. This may eventually become the situation in countries such as Brazil, China and India, where the prevalence of HIV/AIDS is high and the majority of the population cannot afford the cost of patented medicines. Demand will be ongoing and probably predictable in this situation because the Government can designate a small number of state-run manufactures to produce the drugs for a variety of domestic sources. Yet because Brazil, China nor India wants to infringe the TRIPS Agreement, compulsory licenses will predominantly be for domestic use, if they are granted at all. Nonetheless, domestic use of compulsory licenses may hopefully be the impetus to eventually use the flexible provisions in the TRIPS Agreement to enable export of affordable versions of second and third-line ARV medicines to developing countries. Although the problem of producing affordable generic versions of second-line, third-line and future-line ARV medicines is certainly immediate, there is still an on-going and urgent need to supply basic first-line treatments to people suffering from HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. India will continue to play a major role in the provision of these drugs, but as the next two sections will show, Brazil and China have the potential to become major exporters and suppliers of these drugs as well. Both countries will perhaps also have an opportunity to change the old guard as the Indian pharmaceutical industry enters a new era of growth under its recently established TRIPS compliant intellectual property system. India followed the lead of many developed countries, such as Japan, Italy and Switzerland, who only began granting patents in the pharmaceutical industry after developing a national drug manufacturing industry.23 Generic production of medicines will still play an important role in the Indian drug sector, but there will certainly be greater investment in research and development companies and biotechnology start-ups.24 Consequently, Brazil and China may be better poised to produce generic versions of those second-line, third-line and future-line ARV medicines. Heather Watts, “Bill C-9: The Complaints of the Generic Drug Manufacturers and the Perspective of Developing Countries”. Online: http://www.dww.com/articles/bill_c-9.htm 23 Supra note 11 24 Nandini K Kumar et al., “Indian Biotechnology – Rapidly Evolving and Industry Led” (2004) 22 Nature Biotechnology Supplement DC31 22 Section II – Brazil Domestic production of generic ARV medicines in Brazil is closely tied to the country’s 1996 public health initiative (Law 9.113/96)25 to provide free medications to all HIV/AIDS infected persons in need. In 1992, Brazil had the highest rate of HIV/AIDS infection in the world, and the World Bank estimated that 1.2 million people in Brazil would be infected with HIV/AIDS by 2000.26 Eight years later, however, the number of cases remained stable at 600,000, due to strong prevention and treatment campaigns.27 Brazil is the first developing country to prove that it is possible to provide essential medicines to those in need, and that it is actually cost effective to do so in terms of overall savings to the health care budget. To achieve success, Brazil has been able to meet two essential conditions: 1) increase local production of generic medicines and 2) negotiate for lower prices of imported drugs.28 In addition to procurement of medicines, other factors were in place to facilitate access to drugs in Brazil, such as a consensus on the use of ARV therapy, and the development of a logistical system for the purchase, storage, distribution and availability of medicines.29 However, Brazil’s success story has been turbulent, and this section will follow the development of the domestic drug industry in Brazil to provide an example of the struggles a developing country may encounter in trying to domestically produce generic versions of patented drugs in accordance with the TRIPS Agreement. This section will also analyze the potential role for Brazil to become a major exporter of ARV medicines. An established pharmaceutical industry has existed in Brazil for many years, and today this sector includes research-based pharmaceutical companies, generic drug manufacturers, and biotechnology companies. Currently, there are approximately 370 pharmaceutical companies in Brazil, of which 296 are domestic and 74 are foreign owned.30 Until the end of the 1980’s, most pharmaceuticals sold in Brazil were locally produced.31 However, import laws were liberalized in the early 1990’s, allowing 25 Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)/WHO/Ministry of Foreign Affairs France, “Improving Access to Care in Developing Countries: Lessons from Practice, Research, Resources and Partnerships” (2002) at 82. Online: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/prev_care/en/ImprovingaccessE.pdf 26 Martin Foreman, “Patents, Pills and Public Health – Can TRIPS Deliver?” (2002) Panos Report No. 46 at 35. Online: http://www.panos.org.uk/PDF/reports/TRIPS_low_res.pdf 27 Ibid 28 Ibid 29 Supra note 26 at 80; Brazilian National Drug Policy (1998) “established a basis for activities and priorities, including the adoption of a national essential medicines list, health-related regulation of medicines, re-orientation of pharmaceutical services, promotion of rational drug use, scientific and technological development, and promotion and production of pharmaceuticals”. Cited in the WHO Commission on Intellectual Property Rights, Innovation and Public Health (CIPIH), Background Document for 3rd Commission Meeting Brazil, Jan 31 – Feb 04, 2005 (Commission Report). Online: http://www.who.int/intellectualproperty/events/en/BackgroundPaper.pdf 30 Industry Canada Report: Brazil, Country Commercial Guide FY 2003: Leading Sectors. Online: http://strategis.ic.gc.ca/epic/internet/inimr-ri.nsf/en/gr110629e.html. Note that the UK Commission Report (see FN30) indicates that there are 450 authorized drug manufacturers in Brazil, but the source is written in Spanish and therefore I cannot confirm this number (OMS. Cuestionario sobre estructuras y procesos de la situatión farmacéutica nacional: Brasil. Fecha: 09/06/2003.) 31 Supra note 27 at 36 subsidiaries of multi-national corporations to increase foreign imports into the Brazilian market. Brazil is the 11th largest pharmaceutical market in the world as per drug sale figures, and accordingly has been targeted by research based multi-national drug companies as a strategic market.32 In response to the increase in drug importation, the Brazilian share of the market substantially decreased, and by the year 2000 drugs from multinational companies accounted for 80% of sales.33 The pharmaceutical market in Brazil in general is highly fragmented and no single company has greater than five percent of the market.34 Companies also tend to specialize within the therapeutic market, which decreases the overall level of competition.35 Due in part to the need to ensure access to essential medications, Brazil initiated a policy to stimulate domestic pharmaceutical production through the manufacture of generic medicines. The Government of Brazil enacted Law 9.787/9936 in 1999 (the Generic Law) to establish guidelines for the introduction of quality generic drugs into the Brazilian market, as well as to increase competition for non-brand name drugs. For example, Article 3, Paragraph 2 of Law 9,787/99 states that if a generic and patented drug cost the same amount, the Unified Health System (SUS) shall give purchasing preference to the locally produced generic drug. The strategy has arguably worked, as there are now 56 Brazilian companies manufacturing generic drugs, 27 of which are nationally owned.37 Domestic generic companies generate 80% of the generic drugs marketed in Brazil, and the generic industry aims to reach 30% of the overall drug market share by 2007.38 Brazil’s generic production policy has also proved attractive to foreign investors, who have been incorporating generic plants in Brazil since 1999.39 Pro-Genéricos, Brazil’s generic pharmaceutical manufacturers’ association, has data that apparently supports the position that the pro-generic policy has strengthened the local pharmaceutical industry in Brazil.40 The association calculates that the generic industry has invested roughly R$1 billion into the construction and modernization of pharmaceutical companies in Brazil. Before the Generic Law was introduced in 1999, Brazilian companies had already been producing generic drugs including a small number of ARV medicines. These ARV medicines were produced legally and in accordance with the TRIPS Agreement, because they are first-line antiretroviral generics that were patented internationally prior to 1997. Between the years 1945 to 1997, Brazil did not provide patent protection for 32 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 12 Supra note 27 at 36; Multinational companies are currently responsible for supplying 70% of the internal market, not including direct sales to the Government (see FN 25 (UK Commission Report) at 12, which cites FebraFarma, the Brazilian Federation of the Pharmaceutical Industry, at the following web-site in Portuguese: http://www.febrafarma.org.br/areas/febrafarma/quem_somos.asp) 34 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 5 35 Ibid 36 Law 9,9787 English translation online: http://www.anvisa.gov.br/hotsite/genericos/legis/leis/9787_e.htm found on the Ministry of Health web-page providing information about ANVISA and generic drugs 37 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 13 38 Ibid 39 Supra note 27, at 36 40 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 13. I am unable to find this information in English. 33 pharmaceutical products or patents obtained by chemical means.41 However, Brazil became a member of the WTO in 1995 and was obligated to amend its patent legislation in accordance with the TRIPS Agreement. The Brazil Industrial Property Law (Law Nº 9.279, of May 14, 1996)42 was revised in accordance with the TRIPS Agreement in 1996 and came into force in May of 1997.43 Although all of the older ARV medicines were patented prior to 1997, newer drugs such as Lamivudine (3TC), Nelfinavir, Efavirenz, Lopinavir+Ritonavir (Zaleestra), and Ritonavir, received patent protection in Brazil because of special pipeline protection.44 Article 230 of the Industrial Property Law authorizes protection for products that were patented protection prior to 1997 if they meet two criteria: they received patent protection in another country and also had not been marketed previously in Brazil. Fortunately, several other ARV medicines were either not eligible or did not file for pipeline protection. They are: Delaviridine, Didanosine, Nevirapine, Stavudine (dt4), Zalcitabine, Indinavir, Lamivudine (3TC) and Zidovudine (AZT).45 AZT was the first drug developed to treat AIDS and was the first ARV legally produced in generic form in Brazil. The drug was manufactured in 1993 by a private firm, and then the public sector firm LAFEPE (Laboratorio do Estado de Pernambuco) also began producing it one year later in 1994.46 By 1999, almost one-half of the ARV medicines purchased by the SUS were from domestic firms, the majority of them being public companies.47 However, there were no drug regulatory standards that applied to copied medicines until the Generic Law was introduced in 1999. Prior to the new law, all non-brand name products were labelled as “similar medicines”. “Similar medicines” simply had to be comparable to brand-name (“reference”) drugs, but did not have to meet requirements of inter-changeability or bio-equivalence.48 The Generic Law imposed technical standards and norms by defining concepts of bioavailability and bioequivalence, and also defining standards for generic, innovative, reference and similar drugs.49 A generic drug, as defined by the Generic Law, must have the same presentation and dosage as the patented drug (must be interchangeable) and it must be approved by ANVISA in relation to its effectiveness, safety and quality. ANVISA is the Federal Sanitary Surveillance Agency, and was created in 1999 in conjunction with the Generic Law to monitor drug regulation.50 It is similar in organization to the FDA or Health Canada and has an overall mandate to protect public health. In relation to pharmaceuticals, ANVISA oversees many aspects of regulation including: registration of both locally-produced and imported drugs, authorizing medical products on the market, 41 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 4. It is interesting to note that Brazil was one of the original 14 countries to sign the Paris Convention of 1883, and has recognized intellectual property protection since its international inception. 42 Online English Translation: http://www.sice.oas.org/int_prop/nat_leg/Brazil/ENG/L9279eI.asp 43 Brazil had the opportunity to delay TRIPS compliance like India until 2005 – see page 7. 44 Supra note 6 (MSF Annex A) 45 Supra note 6 (MSF Annex A) 46 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 9 47 Ibid 48 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 13 49 Supra note 26, at 80 50 Please see www.anvisa.org. All the information that I mention about ANVISA can be found at this link. licensing manufacturers, and providing technical support to the National Institute of Industrial Property in making patent assessments of pharmaceuticals. Generic drug approval by ANVISA did not begin until the year 2000; one year after the Federal agency was created. Drug regulation and quality were certainly areas of weakness in Brazil before ANVISA increased regulatory capacity. For example, between 1997 and 1998, the Ministry of Health received 172 reports of counterfeit drugs.51 After ANVISA was created however, there were only seven confirmed cases of counterfeit drugs between the years 1999 to 2003.52 With respect to quality, a WHO test conducted in 2001 on sampled tracer medications indicated that failure rates of 18% occurred in both public and private laboratories in Brazil.53 In 2003 there were 72 drugs that were apprehended and destroyed and 39 that were withdrawn.54 In terms of approving generic drugs, by December 2004 ANVISA granted 1377 approvals for 284 active ingredients in 5,960 dosage forms.55 Technically there is a 90-day review period for drug application registration, but processing can often take 8 to 12 months. An exception is made for ARV medicines, however, which normally take less than one month to register.56 Overall quality control measures include compliance with Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP)57, certified inspection by ANVISA, and further monitoring of first batches as well as double-checking by university laboratories accredited by the Ministry of Health. 58 Brazil, along with Bolivia, Argentina, Peru, Uruguay and Paraguay, is also a member of MERCUSOR (The Mercado Comun del Sur), which is the South American Common Market. MERCUSOR developed its own non-binding regulations for pharmaceutical production based on WHO recommendations such as the GMP.59 In addition to enacting the Generic Law to improve quality and production of generic medicines, the Brazilian Ministry of Health also initiated a strategy to invest in local manufacturers to increase local production and local sales to the Government.60 The policy worked. For example, before 1999 Brazilian producers accounted for only 18% of antiretroviral medicines purchased by the Government.61 But two years later, the Federal manufacturer Far-Manguinhos alone supplied 30% of medicines used to treat 51 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 11(FN24), which cites the following national counterfeit prevention web-site at: http://www.opas.org.br/medicamentos/docs/HSE_FAL.pdf 52 Ibid 53 Supra note 11, table 9.7 54 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 11 – same Brazilian source as FN52 55 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 11 – citing the following Brazilian source: http://www.anvisa.gov.br/hotsite/genericos/estatistica/geral.pdf 56 Supra note 30 (UK Commission) at 11 57 GMP is an international “system for ensuring that products are consistently produced and controlled according to quality standards. It is designed to minimize the risks involved in pharmaceutical production that cannot be eliminated through testing the final product”. Many international health organizations, such as UNICEF, insist on GMP inspections. Supra note 11. 58 Supra note 51 59 OLIVEIRA, Maria Auxiliadora, BERMUDEZ, Jorge Antonio Zepeda, CHAVES, Gabriela Costa et al., “Has the implementation of the TRIPS Agreement in Latin America and the Caribbean produced intellectual property legislation that favours public health?” WHO (2004) Online: http://www.scielosp.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0042-96862004001100005&lng=en&nrm=iso 60 Supra note 27, at 36 61 Supra note 27, at 26 HIV/AIDS.62 By 2001, domestic firms were supplying 63% of ARV medicines used for treatment, and were producing seven ARV medicines in total.63 In 2003, seventeen national manufacturers were producing generic ARV medicines in Brazil, including the one Federal producer Far-Manguinhos mentioned above, and sixteen state-owned companies64. The number of national companies is now apparently 27 out a total of 56 generic companies in Brazil.65 In 2003, public laboratories produced 5,110,904,498 units of medicines, which were mainly sold to the SUS. Note that 57% of public laboratories designate the Ministry of Health as their main client, 29% designate the State Health Secretariats as primary clients and 14% indicate the Township Health Secretariat as the major client.66 Yet despite a strong domestic generic manufacturing industry, Brazil still relies heavily on foreign imports. Brazil’s pharmaceutical sales totalled US$6.14 billion in 2004, but Brazil also imported US$1.6 billion in pharmaceutical products.67 Of particular importance is the fact that Brazil is unable to legally produce all of the first-line ARV medicines, and currently imports seven of the fifteen ARV treatments distributed by the Ministry of Health.68 Although the SUS has a large budget for purchasing ARV medicines ($573 million annual budget in 200369), it used nearly 80% of the budget by the end of 2004 to purchase patented medicines.70 Brazil has threatened on several occasions to invoke compulsory licences to produce domestically certain ARV medicines, but has always managed to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies and obtain lower prices.71 Yet, the costs are now too great because of the increased need to use alternative and second-line ARV treatments that are under patent protection in Brazil. Pedro Chequer, Head of Brazil’s AIDS programme, has stated that Brazil’s universal treatment program will not be sustainable unless Brazil is able to produce most of the drugs locally.72 62 Supra note 26, at 83; Far-Manguinhos is also responsible for generic research and development in Brazil, including determining the manufacturing process of final products and reverse-engineering drug compositions. 63 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 9 64 James Love, “Brazil Considers Compulsory Licenses, Defends Doha P6 Deal” IPS news article, September 6, 2003. Online: http://lists.essential.org/pipermail/ip-health/2003-September/005237.html 65 See footnote 38 66 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 11 67 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 5, citing FEBRAFARMA figures in Portuguese online at: http://www.febrafarma.org.br/areas/economia/economia.asp?area=tc 68 BBC News, “Brazil to Break AIDS Drug Patents” Dec 1, 2004 Online: http://news.bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr//2/hi/health/4059147.stm; see note 40 for a list of drugs that Brazil can produce. 69 Supra note 25 (UK Commission Report) at 9 70 Mario Osava, “New Offensive Against Drug Patents” IPS News article, Nov 30, 2004. Online: http://www.ipsnews.net/africa/interna.asp?idnews=26494 71 In 2001, Brazil could no longer afford to continue paying for the antiretroviral medications efavirenz and nelfinavir and managed to lower the price by threatening both Merck & Co. and Hoffman-La Roche that if prices were not reduced the Government would grant a compulsory license to Far-Manguinhos, the Government’s Federal Institute of Pharmaceutical Technology. The Institute had already imported the raw materials from India to conduct testing and research to produce the drugs. See note 75. 72 Supra note 69 Consequently, in November of 2004 the Brazilian Ministry of Health announced that it was implementing plans to manufacture generic versions of between three to five ARV medicines, without the consent of the patent owners if voluntary licensing deals could not be arranged.73 This is a major step for Brazil because despite its ability to manufacture locally, Brazil has faced an incredible amount of pressure to purchase patented drugs directly from international drug manufacturers - from the companies themselves and from the United States74 (the pressure may explain why Brazil amended its patent legislation in 1996 to become TRIPS compliant earlier than was necessary). Yet Brazil managed to pressure the multi-national pharmaceutical companies through negotiations to compromise and reduce drug costs. Brazil’s advantage is found in Article 68 of the Industrial Property Law, a controversial provision introduced along with other TRIPS amendments, which allows for compulsory licensing in the case of abusive use of patent rights. Article 68(1) enables the Government to invoke a “local working requirement”, and demand that a product be manufactured in Brazil. The United States filed a complaint with the WTO in 200175 alleging that the “working requirement” violated the rules set out in the TRIPS Agreement.76 The matter was settled when the United States withdrew the complaint after Brazil agreed to not use the requirement unless it had already negotiated with pharmaceutical companies for price decreases. The “working requirement” provision is important because it enables Brazil to either issue a compulsory license to a local manufacturer to produce the drug or allow parallel importation from the cheapest international source without the patents holder’s consent.77 Brazil is electing to domestically manufacture the patented drugs that the Ministry of Health now considers too expensive to purchase, but Brazil will first try and negotiate voluntary licences in respect of the earlier WTO dispute. Brazil therefore has asked for voluntary licenses from Merck (Efavirenz), Abbot Laboratories (Lopinavir and Ritonavir), and Gilead (Tenofovir) to allow local manufacture of their ARV medicines.78 These companies have until April 4th, 2005 to devise a suitable arrangement; otherwise the Brazilian Ministry of Health has stated that it will permit compulsory licenses for domestic manufacture of the medications.79 In addition to these drugs, Brazil has already received permission from Merck to produce the drug Efavirenz, which is under patent until 2012.80 Brazil capped the price of Efavirenz at $1.75US, a price that is not profitable for Merck, but still too expensive for Brazil to procure. 73 Supra notes 69 and 71 Oxfam, “Brazil Fights for Affordable Drugs Against AIDS” (2001) 9(5) Pan Am J Public Health 331. 75 Richard Elliot, “US Files WTO Complaints against Brazil Over Requirement for “Local Working” of Patents” (2000) 5(4) Canadian HIV/AIDS Policy and Law Review. Online: http://www.aidslaw.ca/Maincontent/otherdocs/Newsletter/vol5no42000/patentsandprices4.htm 76 It can be argued that the “working requirement” rule is a safeguard only to be used in the case of “abuse of rights or economic power”, and therefore does technically comply with the TRIPS Agreement – Ibid. 77 Supra note 75 78 Reuters, “Brazil Requests Voluntary Licensing for AIDS Drugs to Treat More Patients, Reduce Costs of Importing Patented Drugs, March 17, 2005. Online: http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/medicalnews.php?newsid=21378# 79 Ibid 80 Mike Palmedo, “Merck to give Brazil voluntary license for Efavirenz” Bloomberg, Decemeber 3, 2004. Online: http://lists.essential.org/pipermail/ip-health/2004-December/007216.html 74 As of the date of this paper (April 28, 2005), Brazil has still not issued compulsory licenses for any of the drugs mentioned in the preceding paragraph. Overall, Brazil is not yet self-sufficient in supplying sufficient ARV medicines to meet local demand.81 As outlined above, Brazil has a large domestic pharmaceutical industry, but patents on several drugs prevent its generic manufacturers from producing the entire first-line regimen otherwise known as a fixed-dose combination. A first-line regimen was designed for use in resource-limited settings, such as Sub-Saharan Africa, by the WHO. The WHO recommends that in resource-limited settings, a single first-line regimen should be identified for the treatment of the majority of new patients. This regimen would consist of 2 nucleoside analogs and either a non-nucleoside or Abacavir, or a protease inhibitor. Zidovudine plus Lamivudine AZT/3TC is the initial recommendation for a dual nucleoside analog with d4T/3TC, AZT/ddI and ddI/3TC as possible alternatives. Efavirenz and nevirapine are recommended non-nucleosides, while recommended protease inhibitors include ritonavir-boosted PIs (indinavir, lopinavir, saquinavir) or nelfinavir. A second line regimen should be chosen to substitute first line regimens when needed (for toxicity or treatment failure).82 Brazilian manufacturers are able to produce the first component of the fixed-dose combination, which is the AZT/3TC drug. GlaxoSmithKline also produces the AZT/3TC drug, which carries the trade name Combivir. Combivir is not under patent protection in Brazil, but the tablet formulation is apparently still under examination with the Brazilian Patent Office.83 However, except for Indinavir, all of the other drugs that formulate the second component of the first-line regimen are under patent protection. To provide complete first-line therapy, therefore, Brazil currently has to import several drugs. This also means that Brazil is unable to export complete first-line therapies. Should Brazil issue compulsory licenses for the ARV medicines listed above, it is most likely that the drugs will only be manufactured for domestic supply. It is a major step for Brazil to issue the compulsory licenses, and it is unlikely that Brazil will want to antagonize the United States or major pharmaceutical companies any more than necessary. Neither does Brazil have a provision in the Industrial Property Act to allow export of medicines through compulsory licensing. Although the licenses will help Brazil maintain its public health initiative to provide free ARV medicines to everyone in need, it also means that Brazil will not be able to export many drugs to other areas that need them such as sub-Saharan Africa. Yet Brazil may be a greater exporter in the future because Brazil is in a position to immediately export ARV medicines once they lose patent protection. In 2001 Brazil amended the Industrial Patent Law to incorporate an early working exception (or “Bolar” Provision).84 This exception allows generic companies to complete all of the procedures and tests necessary to register a bio- 81 Supra note 30 (Commission Report) at 9 See: www.who.int/hiv/topics/arv/en Note: in developed countries, such as Canada, the standard of care first line regimen would consist of 2 nucleoside analogues in a bid fixed-dose combination (e.g. Combivir – AZT+ 3TC) plus two protease inhibitors in a bid fixed dose combination (e.g. Zaleestra – ritonavir+lopinavir) at a cost of over $1300 CAD per person for 28 days of treatment. 83 Supra note 6 (MSF Annex A) 84 Supra note 60, at 818 82 equivalent generic drug before the original patent expires. 85 Brazil is sure to take advantage of this provision for domestic needs, and an increase in production is (technically) all that will be necessary to also export these medicines when patents expire.86 There has also been interest expressed by Brazilian generic manufacturers, such as the private firm Cristalia, to export ARV medicines to sub-Saharan Africa. These generic companies insist that they can start additional production lines quickly to produce drugs for export.87 But in order to export the drugs, they must ultimately be priced at a cost low enough to reach those in sub-Saharan Africa. As a final note, it is important to mention that Brazil is already making an international impact in HIV/AIDS treatment through a policy to provide free drugs to other developing countries, as well as provide transfer technology to enable these countries to begin local manufacture of drugs. Brazil has unique experience in the matter of controlling an HIV/AIDS epidemic in a developing country, and has offered to supply other developing countries with advice, technology and drugs for export to help deal with HIV/AIDS.88 In December of 2002, the Brazilian Ministry of Health signed a three-year Memoranda of Understanding with ten countries who received ARV medicines from Brazil worth an estimated US$ 1 million.89 These selected countries were also assisted in developing pilot projects to treat people living with HIV/AIDS. The countries include Guyana, Namibia, Mozambique, Kenya, Burkina Faso and Burundi. Each pilot project offers treatment and care to one hundred HIV positive individuals. On the whole, a thousand patients in each of these countries received Brazilian AIDS drugs through the "International Cooperation Program for HIV and AIDS Prevention and Control Activities for Other Developing Countries", launched during July 2001 by the Ministry of Health at the International AIDS Conference, held in Barcelona, Spain.90 Brazil continues to expand the program to other countries in Africa as well as South America, which now also includes training of medical personnel.91 Section III – China Generic manufacture of ARV medicines has evolved at a slower pace in China than in Brazil. Brazil was faced with an HIV/AIDS epidemic almost a decade earlier than China, and was one of the pioneers in the generic production of ARV medicines. Brazil recognized the serious situation posed by HIV/AIDS and initiated strong prevention as well as affordable treatment campaigns, whereas China, in contrast, has been slow to acknowledge the recent emerging public health threat of the HIV/AIDS disease within its borders. With respect to legal ability to generically manufacture ARV 85 Ibid Patented drugs that will soon lose protection include Saquinavir (Dec 2010) and Abacivir (2009). 87 CBS News.com, “Brazil’s Drug Copying Industry”, Sept. 25, 2003. Online: http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2003/09/25/health/printable575168.shtml 88 Brasilia, Ministry of Health, Press Release issued December 19, 2002. Online: http://www.cptech.org/ip/health/c/brazil/brazil12192002.html 89 Ibid 90 Ibid 91 “Brazil Exporting HIV Treatment to Six Countries”, ACAN-EFE (translated from Spanish to English by World News Connection) August 26, 2004. Dialog® File Number 985 Accession Number 194500771 86 medicines, China faces basically the same limitations as Brazil. For example, although many of the first-line ARV medicines received international filing dates several years before China’s patent laws were amended, China allowed “administrative protection” for several of the common ARV medicines. Yet despite the legal and manufacturing ability to produce many other first-line ARV medicines, until recently Chinese generic companies differed from their Brazilian counterparts and produced either no ARV medicines or low quality illegal versions.92 It has only been in the last three years that Chinese generic firms have been manufacturing state licensed first-line ARV medications – probably in recognition of the growing HIV/AIDS problem in China itself, and an expanding international market for the drugs. This section will analyze the connection between the rise of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in China and changes to the pharmaceutical industry in China, to show how the country has somewhat overnight become a world supplier of anti-AIDS drugs materials and a growing exporter of inexpensive HIV/AIDS medicines. The generic medicine production capacity of China is substantial. The pharmaceutical industry in China has grown by an average of 17.5% per year since 197993, when China first adopted economic reform and open-door policies.94 In 2000, production of raw pharmaceutical materials reached 240,000 tons, the second highest amount globally after the United States.95 Within China there are thousands of small manufacturers that produce traditional medicines and low quality generics, but only a few large pharmaceutical companies.96 It is estimated that there are over 7,500 manufacturers in China,97 and that 97% of the drugs they produce are generics.98 According to the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, China is designated as having “innovative capability” for medicine production.99 This classification means that China has discovered and marketed at least one new pharmaceutical between 1961 and 1991. Brazil, in contrast, is classified as having “reproducer capability”, making both active ingredients and finished products. Although China has produced only two successful new drug formulations, the future of China seems likely to proceed in the area of research and development as international pharmaceutical companies and foreign investment replace former publicly owned companies.100 In order to place the Chinese pharmaceutical situation in context, it is necessary to describe recent amendments to Chinese patent legislation. China became a member of the WTO in 2001, but voluntarily amended its patent legislation to become TRIPS compliant several years earlier in anticipation of joining the WTO. The earliest patent law in China was enacted in 1984 (1984 Law), and based on the level of development at 92 Supra note 27, at 22 Ibid 94 Supra note 12 95 Supra note 27, at 22 96 Supra note 11, at 110 97 Supra note 11, at 2 98 Supra note 27, at 23 99 Robert Balance, Janos Pogany and Helmut Forstner for UNIDO, The Worlds’s Pharmaceutical Industries (England: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 1992) at 8, table 1.1 100 Supra note 27, at 23; supra note 12, at 14 93 the time, did not recognize patent protection in major areas of national interest such as pharmaceuticals.101 There were several other provisions in the 1984 Law that hindered China’s economic and trade reform, and consequently China amended the 1984 Law in 1992 (1992 Law).102 The 1992 Law, enacted on January 1, 1993, complied with the proposed TRIPS Agreement (which itself was not finalized under 1994) and incorporated all of the necessary provisions of the finalized TRIPS Agreement. Consequently, Article 25 of the 1992 Law was amended to include pharmaceutical patents; and importantly, compulsory licensing provisions were amended under Article 52 to include the ability to issue a compulsory license for domestic manufacture “where a national emergency or an extraordinary state of affairs occurs, or where the public interest so requires”.103 However, regulations specifying how to implement compulsory licenses were either absent or ambiguous. As China proceeded through the 1990’s, the seeds for rapid dissemination of the HIV/AIDS virus were planted. Many injection drug users living in provinces that border countries with high HIV/AIDS infection rates, such as Yunnan, acquired the disease throughout the decade.104 Injection drug use is now the most prevalent cause of the spread of the disease in China, accounting for two-thirds of victims.105 China also had a terrible tainted blood problem that arose from an unsafe blood collection system during the 1990’s. Commercial blood banks would pool blood from paid donors, separate out the plasma, and then return some of the blood to the donors to facilitate more frequent blood donation.106 Yet donated blood was not screened for HIV/AIDS, and incidents of contamination were overlooked, leading to the infection of 250,000 blood donors who participated in the re-injection system.107 It was not until the late 1990’s that AIDS symptoms began to appear noticeably in the Chinese population, unlike in Brazil where the disease has been a threat for over a decade. However, there were no quality generic ARV medicines being produced domestically during the 1990’s even though China could legally manufacture several of the drugs. The spectre of this public health crisis though may have been the impetus for China to finally being producing generic first-line medications a few years later. A large number of HIV/AIDS medicines have not been patented in China because the original patent applications were filed prior to 1993. Although China did not recognize product patents until January 1st of 1993, the Government permitted “administrative protection” for pharmaceuticals that had obtained a foreign patent between January 1, 1986 and January 1, 1993.108 The Regulations on Administrative Protection for Pharmaceuticals (the 1992 Regulations) came into force with the 1992 101 Supra note 12, at 15 Supra note 12, at 16 103 Supra note 12, at 16-17 104 John Cohen, “Poised For Take-off?” (2004) 304 Science 1430, at 1433 105 Ibid, at 1431 106 Ibid 107 Ibid; also see Patrick E. Tyler, “China Concedes Blood Product Contained AIDS Virus”, New York Times (10/25/1996) – Online: http://www.aidsinfobbs.org/library/cdcsums/1996/0963 108 Gao Xia-Yun, “An Introduction to Administrative Protection For Pharmaceuticals”, (1998) 9 Duke J. of Comp. & Int'l L. 259 102 Law, and set out the requirements for administrative protection which are as follows: the pharmaceutical product must have been granted a product patent in the U.S. during the period January 1, 1986 to January 1, 1993; it must have been approved for marketing in the U.S. by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA); it must not have been sold in the territory of China prior to an application for protection; and the patentee must have signed a contract for manufacturing or distribution with a Chinese enterprise.109 Prior to the 1992 Regulations coming into force, China signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the United States, agreeing to provide administrative protection.110 Subsequent to the enactment of the 1992 Law, China signed further bilateral agreements on administrative protection in succession with Switzerland, the European Union, Japan, and Norway.111 The Office of Administrative Protection for Pharmaceuticals reviewed all of the applications, and those accepted were granted seven and one half years of protection. I have not been able to determine with confidence which of the ARV medicines were granted administrative protection, but the patent duration for both Saquinavir and Lamivudine (3TC) indicates that these drugs probably received additional protection rights.112 These two drugs both have a priority filing date of 1989, and have been granted patent protection by the USPTO and EPO until 2010. Patent protection for both these drugs expires in 2005 (December 12th and February 8th respectively)113 in China, which is five years earlier than international standards. According to the expiry date, administrative protection would have been granted in 1997, which may mean that it took more than three years to process the applications. ARV medicines that have probably never been patented in China include Delaviridine (priority date 1989), Nevirapine (priority date 1989), Stavudine (dt4 – priority date 1986), Indinavir and Ritonavir (priority date 1992).114 The drugs Didanosine (ddI), Zalcitabine and Zidovudine (AZT) have never been eligible for patenting in China because their priority date is 1985. Although China has the legal ability to produce generic versions of several ARV medicines, the Chinese Government has been slow to sanction generic production. Beginning in 2001, however, key changes occurred to make China an important producer in the supply of low-cost ARV medications. In 2001, two Chinese manufacturers applied for “compulsory licenses” to produce four ARV medicines.115 A small private company known as Shanghai Desano Biopharmaceutical Co., applied to the State Drug Administration to make ddI, d4T and Nevirapine. The state-owned Northeast General Pharmaceutical Factory (NEGPF) also applied during 2001 to produce AZT. Both 109 Ibid Ibid 111 Ibid at 262 112 Supra note 6 (MSF Annex A) 113 Ibid. Please note that 3TC has 3 separate patents depending on the formulation, and that the patent on just the original formulation just expired in China in February 2005. 114 Ibid. 115 Leslie Chang, “China Companies May Use Patent Law to Produce Cheap Drugs for AIDS”, Wall St. J., Nov. 15, 200. Online: http://www.aegis.com/news/wsj/2001/WJ011103.html. Note that the terminology “compulsory licensing” is confusing, because the four drugs were not under patent protection at the time of request. The terminology could mean instead that the Chinese Government recognized the manufacture of these drugs as legal and in accordance with GMP. 110 companies were already producing raw materials for AIDS drugs and were exporting them to Brazil and India.116 The HIV/AIDS infection rate was beginning to rise at this time, and the Chinese Government probably began to realize the importance of domestic production to lower the price of necessary medicines.117 In August 2002, the Chinese Government allowed NEGPF to manufacture d4T and AZT for domestic production, and in September of the following year the Government also granted approval to Shanghai Desano to produce ddI, d4T and Nevirapine for domestic use as well as APIs for export.118 Shanghai Desano plans to produce enough drugs to supply 500,000 people in China each year with combination therapy, at treatment costs between US$435 - $560 per year.119 Xiamen Mchem Pharma Group was granted the right to produce AZT in 2002, for both the domestic Chinese market and for export to thirteen countries in Africa.120 The thirteen African countries are not named, but information indicates that Xiamen had to wait for compulsory licenses to be issued by the countries to allow import. The countries are probably members of ARIPO, because AZT is currently under patent with ARIPO.121 The fourth pharmaceutical company to receive approval from the Chinese Government for ARV manufacture both domestically and for export is Zhejiang Huahai Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd. It is the first Chinese generic company to produce ddI in tablet form, and intends to produce 500,000 tons of the tablets eventually.122 Although China has the capacity to produce and export several generic versions of first-line ARV medicines, the focus of generic production may remain domestic for the next few years as China deals with a growing HIV/AIDS crisis further hampered by specific drug patents. Recognizing the public health issue, the Chinese government announced a new initiative in 2003 to provide free ARV medicines to the many people in China who cannot afford to purchase them otherwise.123 Yet a major treatment problem exists in China because although many of the first-line ARV medicines such as AZT and nevirapine are not patent protected, the fixed dose combinations Combivir (AZT and 3TC) and Trizivir (AZT, 3TC and Abacivir), as well as the ingredient 3TC have been patented in China.124 Consequently, Chinese manufacturers have only been able to provide unfavourable combinations of ddI, d4T, AZT and nevirapine.125 The four drugs often cause toxic reactions when combined to make double nucleoside analogs, and also are susceptible to high levels of resistance by the virus.126 Glaxo Smith Kline (GSK) 116 Ibid People’s Daily On-line English version, “China-made anti-AIDS medicine benefiting developed countries”(May 23, 2004). Online: http://english.people.com.cn/200405/23/eng20040523_144142.html 118 TREAT Asia , “TREAT Asia Special Report: Expanded Availability of HIV/AIDS Drugs in Asia Creates Urgent Need for Trained Doctors” (July 2004) Appendix 1. Online: http://web.amfar.org/treatment/news/TADoc7.pdf 119 Ibid 120 Ibid 121 The patent for AZT will expire internationally in 2006 122 Supra note 119 123 Supra note 105, at 1430 124 Supra note 6 (MSF Annex A) 125 Supra note 105, at 1433 126 Ibid 117 owns the patents for Combivir and Trizivir, as well as 3TC, which is an active ingredient in both combination drugs. The patent for 3TC (Lamivudine) just expired on February 8th, 2005, so Chinese manufactures should be able to make alternative double nucleoside analogs such as d4T/3TC, AZT/ddI and ddI/3TC.127 GSK had been unwilling to voluntarily license 3TC to Chinese manufacturers, because the drug can also be used in lower doses to treat hepatitis B and therefore would dilute the market for the drug.128 Now that 3TC is off patent, it remains to be seen whether GSK will allow voluntary licensing of Combivir in China. The patent for Combivir is expected to expire in 2007.129 Interestingly, China may now find that itself in the same position as Brazil with respect to issuing compulsory licenses for domestic manufacture. There are alternatives to Combivir, but it is still the best double nucleoside analog and is very important to providing appropriate treatment for HIV/AIDS infected persons. Fortunately, the compulsory licensing provisions for domestic manufacture of pharmaceuticals have been amended recently to improve ease of use. China did have the option of granting compulsory licenses under the 1992 Law, but in addition to weak provisions, the Government refused to grant such licenses in order to prove China’s determination to protect the rights of patent holders.130 However, in 2001 and 2003, China further amended its compulsory licensing provision to make it adhere to the requirements listed under Article 31 of the TRIPS Agreement. The June 2003 amendment, which is an Order of the Commissioner of State Intellectual Property Office No. 31, entitled “Compulsory Licensing Method”, seems to facilitate the use of compulsory licenses in a positive manner.131 It aims to provide clearer guidance for the following situations: application for a compulsory license by the manufacturing entity; method by which a patentee can respond to the license request; examination rules to be used by the State Intellectual Property Office; and licensing fee adjudication. If China begins to produce Combivir domestically via compulsory licensing, the door may be opened for the export of the drug as well. Even more so than Brazil, China has the production capability to provide patented drugs for export if it amends its compulsory licensing legislation, allowing exports in accordance with the August 30th Agreement. However, it seems unlikely that either country will want to be the first to issue such licences and both would face strong pressure not to do so. In addition, it appears that China is choosing to focus its role in supply of affordable ARV medicines towards the production and export of active pharmaceutical ingredients (API’s) rather than the finished generic drugs. China and India are the worlds leading suppliers of API’s132, which are almost more important that the actual ARV medicines. The biggest challenge in manufacturing ARV medicines is not producing the final formulations, but rather is producing the APIs for the final formulations.133 APIs are very expensive as well as difficult to produce, and require substantial inventories of raw ingredients and 127 Please see pages 21-22 for a brief summary of first-line treatment regime drug combinations. Supra note 105, at 1433 129 Supra note 6 (MSF Annex A) 130 Supra note 12, at 18 131 Supra note 12, at 21-22 132 Supra note 119, at 6 133 Ibid 128 costly laboratory equipment.134 API manufacturers are also faced with the problem of demand, because manufacture is based on predictability of demand. Both China and India produce APIs inconsistently due to shifts in demand for ARV medicines, which is usually linked to lack of sustainable funding.135 Chinese APIs are inexpensive and of high quality136; they are exported to Brazil, India, Thailand and the Republic of Korea.137 There are two other main reasons why China may prefer to produce APIs rather than ARV medicines. One reason for concentrating on the manufacture of the raw materials is avoidance of patent infringement and TRIPS issues. The United States has China on its 301 list as a country that practices trade violations, and China will probably remain on the list if it attempts to issue compulsory licences for export of patented products. Another reason relates to the fact that many generic producers in China produce illegal copies of drugs, and do not meet quality production standards. Currently only 87 companies have been awarded GMP certification138, despite the fact that under China’s Drug Administration Law proof of GMP is necessary for registration139. China has implemented quality control mechanisms, requiring that samples from four stages of drug development are tested at a national laboratory. The samples are taken during: 1) inspection of the manufacturer; 2) public proceedings; 3) drug registration; and 4) inspection of retail outlet.140 There is not enough evidence about manufacturing practices in China, however, to determine whether the quality control mechanisms apply to all pharmaceuticals companies and whether they are enforced. However, if Chinese generic manufacturers do not curtail counterfeit and low quality production, they will be given severe financial penalty fees, which could total between $400 million to $1 billion US dollars.141 It will take substantial investment as well as increased government drug safety enforcement to ensure drug development standards are met, and it is not likely that China will be able to achieve either requirement soon. Quality of drugs therefore remains a serious impediment to generic production. For example, even the four companies mentioned earlier that have state-licenses to manufacture ARV medicines do not meet the WHO’s benchmark quality standards.142 In addition to TRIPS and drug efficacy compliance issues, a more broad threat to the generic industry is the influx of foreign investment into once publicly owned production facilities. Foreign investment may change the focus of the pharmaceutical companies from generic production to research and development of new drugs. Furthermore, membership in the WTO has removed distribution restrictions and opened 134 Ibid Supra note 119, at 6 136 Supra note 118 137 Supra note 118. In fact, Xiamen Mchem Pharma Group signed a five-year contract with the Brazilian government in September 2003 to become only the third appointed supplier of APIs to Brazil. 138 Supra note 27, at 23 139 Supra note 11 140 Ibid 141 Supra note 27, at 23 142 Procurement, Quality and Sourcing Project: Access to HIV/AIDS drugs and diagnostics of acceptable quality. Suppliers whose HIV-related Products have been found acceptable, in principle, for procurement by UN agencies. Version: 23rd Edition: 4th (Updated: April 2005). Online: http://mednet3.who.int/prequal/hiv/hiv_suppliers.pdf 135 up the market for foreign multi-national drug companies to import pharmaceuticals into the Chinese market.143 During 2005, customs duties on pharmaceuticals will be reduced from 10 to 4.2 percent, which will reduce the competitive edge of domestically produced generic drugs.144 Severe competition in recent years has already caused production companies to reduce profits to a minimum.145 It is also important to note that China is the only developing country that exports most of its pharmaceuticals to industrialized countries.146 Consequently, without a steady source of demand for ARV medicines from African countries, Chinese manufacturers will not find the market lucrative. Only domestic need for ARV medicines may initiate more Chinese production of these drugs. Therefore, in the face of privatization and a market-based economy, China will have to make it a policy to prioritize production of ARV medications. Conclusion This paper has analyzed whether Brazil and China have the production capacity, as well as legal ability under the TRIPS Agreement, to supply necessary inexpensive ARV medicines to countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Although neither country has the export ability of India, each country has the potential to contribute significantly to the world supply of affordable medicines. As several HIV/AIDS drugs lose their patent protection during the next few years, Brazil will be able to manufacture these drugs immediately due to early working provisions found in the Brazilian Industrial Property Law. China already plays a very important role in the production of medicines by supplying high quality yet inexpensive active pharmaceutical ingredients to India and Brazil for the manufacture of ARV medicines. China also has a very large generic industry, but issues of quality and illegal manufacture plague it. However, as the HIV/AIDS infection rate steadily rises in China, there will probably be more incentive to increase local production of quality ARV medicines to contain the disease before disease reaches epidemic proportions. While both countries have the ability to produce several first-line ARV medicines, they too are caught by the problem of how to produce patented second and third-line treatments. Although neither country is keen to break existing patents, the HIV/AIDS treatment situation demands that both countries will have to eventually issue compulsory licenses for domestic production. This would be a major step in the fight to provide affordable HIV/AIDS treatments, as it may in the future open the door for export of these medicines via compulsory licensing. 143 Supra note 27, at 23 Ibid 145 Ibid 146 Supra note 11, at p24 (chapter 3) 144