BRITAIN: COUNTRY AND CULTURE 1: AN OVERVIEW

advertisement

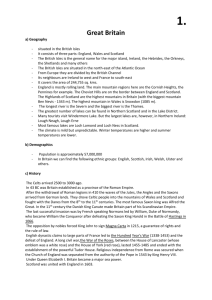

BRITAIN: COUNTRY AND CULTURE 1: AN OVERVIEW Dear Students, The purpose of this course is to encourage you to gain an insight into the essential institutional, political, social and cultural developments that have made up the ingredients of today’s Britain. The course adopts a historical approach, taking in developments since the Celtic period until the Act of Union with Scotland in 1707. Topics include Roman Britain, the Viking and Danish invasions, the Norman invasion, Anglo-French relations, the troubles with Ireland and Scotland, and religious problems. The course takes the form of lectures, which are but the tip of the iceberg, simply providing you with the impetus to research and study further. You are encouraged to share the results of your study with the class, helping not only your fellow students, but the lecturer. We are, after all, in the same boat, even if I am at the helm. Evaluation will be by unseen short written essays. I shall provide some examples of questions at the end of this hopefully helpful guide. We kick off with the beginning of the arrival of the Celtic tribes in Britain around 500 BC. One of the main tribes was called the Brythons, hence the Roman name ‘Britannia’. Another important tribe was known as the Goidels, or Gaels. Hence, incidentally, the name ‘Gaul’. The Gaels were pushed northwards and westwards. Interestingly, the Roman Tacitus wrote that the languages of Gaul and Britain were similar. At any rate, the not very well organised and quarrelsome tribes were no match for the Romans who ,having taken a look in 55 BC, invaded properly in 43 AD, under the emperor Claudius. Unlike Gaul, where the Romans established themselves definitively, Britain was seen as more of an important military outpost. The Romans nevertheless built many roads, developed London (Lundinium), founded cities (‘chester’ derives from ‘castrum’), introduced viticulture, the alphabet (at least to the elite), and later on Christianity. Unable, or disinclined, to conquer the whole of Scotland, ‘Hadrian’s Wall’ was constructed to keep out the marauding tribes from Caledonia (Scotland), and yet further north, the ‘Antonine’ Wall was constructed. It 1 proved difficult to hold. One Roman legion, the Ninth, went north to campaign against the Pictish tribes, but never returned. By 410 AD, the last Roman soldiers had left, to defend Rome against marauding barbarian tribes, and in 449, a massive invasion of barbaric and pagan German peoples invaded Britain, the three main tribes being the Angles, Saxons and Jutes. For two hundred years the situation was chaotic, with the Celts being killed and pushed westwards. Some escaped to western Gaul, hence the name ‘Bretagne’. The AngloFrench story of King Arthur, a Romanised Christian Celt, goes back to this period. By the early six hundreds, things were beginning to settle down again, and various Christian Celtic priests were returning from Ireland to again Christianise Britain. Southern Britain was divided into various kingdoms. But now, towards the end of the Eighth Century, began another wave of invasions, those of the Vikings, both from northern Scandinavia and Denmark. First they pillaged and killed, but then began to settle. Under King Alfred, who ruled Wessex and enjoyed much influence in the South, hard fighting took place between his armies and those of the Danes, ending with an agreement to divide the future England into the South, under Alfred and his successors, and what was known as the ‘Danelaw’ to the north. Further north, in Ireland and Scotland, the northern Vikings held sway. By the time of Ethelred, the area we know as England was beginning to come together, Edgar having conquered the Danelaw. However, tensions continued with the Danes who, under Sweyn, King of Denmark, invaded England in 1003, Ethelred fleeing to Normandy in 1013, but returning as king on the former’s death in 1014. In 1016, King Knut (Canute) of Denmark cut the Gordian knot, and conquered England (some people were now beginning to refer to the south of Britain as ‘Englalond’, the land of the Angles). He and his sons ruled until 1042. Since there was no direct successor, Edward the Confessor, connected to the Wessex blood of Ethelred, took over as king. He is said to have liked the Norman-French scene, spending a fair amount of time in Normandy, and promised the throne to his cousin William the Bastard, Duke of Normandy. The Pope supported this. When Harold Godwinson tried to take the throne of England, following his victory at the Battle of Stamford Bridge over his own brother Tostig and the king of Norway, Harald Hardrada, he then had to march south rapidly, to contend with William’s army at the Battle of Hastings. His army was defeated, and he was 2 killed by an arrow in the eye, as we see from the ‘Bayeux Tapestry’. The year 1066 is a veritable landmark in British history. William quickly subdued the country, and the Normans - who, let us remember were descended from Danish Vikings who had settled in northwestern France, becoming ‘more French then the French’ – now transformed England, building castles, cathedrals, and writing the ‘Domesday Book’, which recorded every piece of property in the country. Greece has still to have one! French aristocratic systems were introduced, and French became the official language of England. Perhaps the biggest impact was linguistic, with thousands of French words being imported into English. The Normans strengthened and organised England at the same time as France was itself strengthening, and introduced an inextricable link between the two young countries that was to plague them for centuries to come. The first most obvious link was that William the Bastard was not only king of England, but Duke of Normandy, in the capacity of which he was subservient to the French king. During the reign of King John (famous for the Magna Carta), Normandy was lost to King Philip of France. Dynastic disputes increased the tensions. We need to bear in mind here (to simplify a complicated story) that the powerful kings of the day ruled over vast domains in both countries at various times. If you married a king’s daughter, then that gave you a claim to land. At any rate, most of the tensions were dynastic, with various claims and counter-claims. Matters came to a head when Edward III claimed the throne of France, and in 1337, his armies invaded France. There was a series of wars, lasting until 1453, later known as the Hundred Years’ War. For much of the war, the soldiers from England (and Wales, by now under the yoke of England), did well, winning battles such as those of Crécy (1346), Poitiers (1356) and Agincourt (1415), but then the tide turned (remember the story of Joan of Arc?), and by 1453, only Calais remained under the English crown, to be lost during the reign of Queen Mary a hundred years later. Significantly, during the wars, in 1400, English replaced French as the official language of England. It can be said that these wars defined to a considerable extent the very characters of France and England. They did not lead to peace: quite the contrary, since wars between the two countries were to continue on and off until 1815. By the end of the Hundred Years’ War, England was approaching the end of the rule of the French-connected Plantaganet dynasty, which passed to two 3 junior branches respectively, the Houses of Lancaster and York. The matter was finally settled with the final battle of the Wars of the Roses (York white and Lancaster Red), when King Richard III, a Yorkist, was killed at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485. The battle has been immortalised by Shakespeare, with Richard’s plea, before he was killed: ‘A horse, a horse, my kingdom for a horse!’ Henry Tudor, a Lancastrian, then became Henry VII of England. By marrying the daughter of the deceased Yorkist king, Edward IV, he united the two houses. Under the Tudor dynasty, England grew stronger. Henry VIII reigned from 1509 (the same year as my old school, St. Pauls, was founded) to 1547. During his reign, he managed to wage several wars with France and Scotland, and conquered Ireland, or at least managed to bring a large part of the latter under English control. Although he is well known for having married six times (and had two wives executed), he goes down in history as having broken with Rome, apparently furious at not being granted an annulment of marriage by the Pope. He declared himself head of the church in England and destroyed the monasteries, many monks being treacherously killed, thereby also diluting what was once good English cuisine. Despite his undoubted cruelty, he built up the navy, and can certainly be depicted as the monarch who made England far less dependent of the continent of Europe than hitherto. He also established Grammar Schools, where Greek and Latin were taught, thus contributing to intellectual life. As we have seen, religion plays a large part in the political evolution of England under Henry VIII. Let us now depart from chronology, and look briefly at the clash between Church and State that bedevilled England – and indeed the whole of Christendom – in the Middle Ages and later. When Rome had collapsed, the only organisation capable of re-establishing a semblance of order was the Church, so it was inevitable that in would by default assume much political power. In England this manifested itself in the murder of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas a Becket, in 1170, as well as in Henry VIII’s unbecoming behaviour. In those days the Pope’s power of excommunication meant a great deal. (I am tempted to wonder whether, if the Pope had threatened Bill Clinton with excommunication, he would have gone ahead with bombing the Serbs. But of course, there was no chance of that, since the 4 Vatican was the first state to recognise Croatia.) At any rate, religion was now to play an important role in Britain. Henry’s daughter Queen Mary (Tudor) was a Roman Catholic who took England back to Roman Catholicism, which involved the burning of a few hundred recalcitrants. Owing to her marrying King Philip of Spain, England fell under Spanish and Roman Catholic influence. But when Mary’s half-sister, the Protestant Elisabeth I, came to the throne, a reversal took place, and Spain and the Papacy became enemies: with the blessing of the Pope, the Spanish Armada set sail to conquer England, but were unable to land and march on London, owing to the English Navy’s small boats burning Spanish galleons by night, Dutch Protestants, and extremely bad weather. The Spaniards were never able to land, and only about half of the fleet of some one hundred and thirty ships returned to Spain, having sailed around Scotland and Ireland, with some starving sailors having had to eat rope to survive. One might now begin to see that some of England’s atavistic fear of Europe has its origins in the Hundred Years’ War and Henry VIII’s attitude, apart from the fact that Britain is an island. To revert to our chronology, we now comment a little on Elisabeth. She had the flexibility to oversee a wonderfully gay period, when the theatre flourished. William Shakespeare is of course the most obvious example. There is however a major stain on Elisabeth’s morality: she approved the treacherous execution of her Roman Catholic cousin, Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland. Well before the execution, Mary was forced to abdicate in favour of her son James. We now move on. Since the unmarried and allegedly virgin queen Elisabeth had no known children, Mary, Queen of Scots’ son James VI of Scotland also became King James I of England. Although born a Roman Catholic, Elisabeth’s acolytes had ensured that he was forced into Protestantism. He came to the throne of England in 1603, suspected by Protestants of being ‘Catholic-friendly’. However, the ‘gunpowder plot’, when the Roman Catholic Guido (Guy) Fawkes and his group tried to blow up the Houses of Parliament, made him less tolerant of Roman Catholicism. He must have had a tough time in the recesses of his mind. 5 He was succeeded by his second son, Charles (Stuart) I, concurrently king of Scotland, who believed that the king had more power than parliament, leading to the English Civil War, fought between Charles’ ‘Cavaliers’ and Oliver Cromwell’s ‘Roundheads’ (they wore their hair short). To cut an unfortunate story short, it ended up with a parliamentary kangaroo court sentencing Charles to death. He was duly beheaded in early 1649. Cromwell’s rule proved to be very Protestant and dictatorial. According himself the title of ‘Lord Protector, he divided up the country into areas ruled by generals. In his various wars, he was particularly cruel towards the Irish. The massacres of Wexford and Drogheda were not pleasant. On his death, his son Richard lasted only two years, to be succeeded by his son Charles II in 1660, his return to England being labelled ‘the Restoration’. England again became a gay and carefree society compared to the Cromwellian period. Charles, who entertained generally good relations with France, actually converted to Roman Catholicism on his deathbed, in 1885. His son James II was a Roman Catholic. Various conspiratorial power centres in England led to them asking the Protestant King of the Dutch Republic, William III of the House of Orange-Nassau, to become king. Cleverly, and perhaps slightly oddly, he had married the daughter of the future James II. When the anti-French William landed in England in 1688 to claim the throne in what is known as the ‘Glorious Revolution’, James naturally refused to give up either the English or Scottish throne. The whole shenanigans ended with the victory in 1690 of William’s forces over James’ French-supported army at the Battle of the Boyne, in Roman Catholic Ireland, with James leaving for France. The war continued in Scotland, ending up with William assuming the Scottish throne, although many a Scot bewailed this. In 1692, the pro-English Campbell clan betrayed their proScottish guests, the Macdonalds, while they were asleep, in what became known as the ‘Glencoe Massacre’. Even to this day, a Macdonald might walk from a room, if he sees a Campbell. Today, problems continue in Northern Ireland, where a large number of Protestants were ‘exported’ during the reigns of Elisabeth and Cromwell. It is hardly surprising that in 1707, during the reign of Queen Anne, the Act of Union between England and Scotland was signed. To this day, some Scots do not accept it. This leads is to some considerations on Scotland, Wales and Ireland, as much a part of Britain as England. We have seen how long it took for England to bring Scotland into 6 her fold. Some of you may have seen the film ‘Braveheart’ which, although not always historically accurate, certainly shows the main story. The Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, when the Scots defeated the English under Edward II, is still a beautiful event for many a Scotsman. Wales succumbed to England much earlier, being taken by Edward I in 1282. In 1301, the youngest son of the English monarch became the Prince of Wales, currently Prince Charles. Ireland is a sad story. Although there was an Act of Union in 1800, activated in 1801, Ireland never completely succumbed. In the 1840’s, at a time of famine, over one million Irish died, and over a further million emigrated, mainly to the United States, out of a population of eight million. The population has never since returned to that level. In 1916, the Irish rebelled, leading to freedom for what eventually became the Republic of Ireland. In Northern Ireland, the tension continues today, with the majority Protestants in the North resisting efforts by Roman Catholic Republicans to unite with the Republic. That, very briefly, is an overview of the course. Of course, we shall also look at strictly cultural matters, such as art, music and education, but the above overview should enable you to learn such things fairly easily. Typical questions from past examination papers have been: ‘What impact did the Normans have on Britain?’ ‘Were the reigns of Queen Mary and her half-sister Elizabeth very different? If you think that they were, explain why!’ ‘Should Scotland have remained independent of England?’ ‘Comment on the role of religion in the development of Britain.’ It goes without saying, almost, that merely learning the above few pages, parrotfashion, will not be sufficient to pass the examination: they represent only a skeletal outline. I shall immediately see through any examination paper that appears to rely 7 only on this brief guide. Most marks will be awarded for evidence of originality and thinking, as well as of knowledge. Have fun! Yours faithfully, William Mallinson 25 October 2011, in the year of our Lord. 8