Cognitive science of religion

advertisement

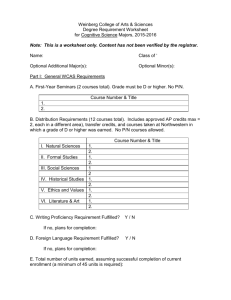

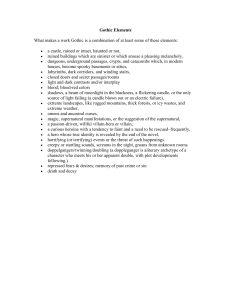

Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION COGNITIVE SCIENCE 266 Cognitive science of religion The ‘naturalness-of-religion’ and ‘memetic-evolution-of-religion’ theses: two sides of the same evolutionary coin Aaron Gehan 3/28/2012 Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION Abstract The ‘naturalness-of-religion’ and ‘memetic-evolution-of-religion’ theses seem to interact and overlap significantly; rather than two competing theories, they appear to be two sides of the same evolutionary coin. The evolved cognitive mechanisms involved in religious thought often become the selection pressures against which religious memes are tested; at the same time, different religious cultures may provide differential benefits for those who subscribe to them and become selection pressures that, in turn, favor the dissemination of the kinds of cognitive mechanisms involved in those religions in the first place. Therefore, the two theories are inextricably intertwined. As such, this paper will explore both the evolutionarily salient cognitive mechanisms that are thought to be involved in religious and supernatural thought processes as well as the co-evolved cultural nature of religion and superstition. Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION Introduction For many, the supernatural seems very natural, intuitive even; around ninety percent of the world’s population claims belief in one or more supernatural deit(y/ies). Religions have risen and fallen, taken various forms, and effectively shaped human history in undeniable ways. Religion has been a part of human culture for thousands of years, but only recently have efforts been made to discern what makes religion so culturally prevalent. For about a decade now, cognitive scientists and psychologists have been inquiring and theorizing as to what factors in the evolutionary history and development of the human species could explain the wide-spread affinity for the supernatural seen today. Their findings have led most in the field of cognitive science of religion to conclude that religion is a phenomenon that follows very naturally from the cognitive composition bestowed upon humans from our evolutionary past, especially when combined with the presence of social and environmental reinforcement of religious thoughts and actions. This belief that the human brain is cognitively primed for religious/supernatural thought is referred to as the ‘naturalness-of-religion thesis’ by Justin L. Barrett (2000). According to Barrett (2000) , “the naturalness-of-religion thesis is currently focused on three main issues: (1) how people represent concepts of supernatural agents; (2) how people acquire these concepts; and (3) how they respond to these concepts through religious action such as ritual (Barrett, 2000, p. 29).” The underlying cognitive mechanisms that result in these three phenomena are considered to be mechanisms that evolved to solve other evolutionarily-salient adaptive problems in the ancestral environment. Somewhat counter to this view is the conception of religion as a sociocultural phenomenon, the result of mimetic evolution. Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION In his book, ‘The Selfish Gene,’ Richard Dawkins (1976) coined and popularized the notion of ‘memes,’ or units of information. Memes are conceptually analogous to genes in that they can be passed from one individual to another, undergo mutation, and be selected for by various determinants; in other words, memes evolve. Religion can be viewed as a collection of evolved memes; religions have slowly changed over the years according to many of the same selection pressures that dictate the evolution of similar institutions such as government, art and sports. The ‘naturalness-of-religion’ and ‘memetic-evolution-of-religion’ theses seem to interact and overlap significantly; rather than two competing theories, they appear to be two sides of the same evolutionary coin. As such, this paper will explore both the evolutionarily salient cognitive mechanisms that are thought to be involved in religious and supernatural thought processes as well as the co-evolv(ed/ing) cultural nature of religion and superstition. Admittedly, this paper is not the first to argue that the two theories work together rather than against one another; Geertz and Markusson made a similar argument in their 2010 paper: “to reach a fuller account of religion, the cognitive (naturalness) and memetic (unnaturalness) hypotheses of religion must be merged” (p. 152). This paper adopts the same attitude. The evolved cognitive mechanisms involved in religious thought often become the selection pressures against which religious memes are tested; at the same time, different religious cultures may provide differential benefits for those who subscribe to them and become selection pressures that, in turn, favor the dissemination of the kinds of cognitive mechanisms involved in those religions in the first place. Therefore, two theories are inextricably intertwined. Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION Naturalness-of-Religion Superstition, a very possible precursor to religion, is thought to be the result of general cognitive mechanisms that operate to decrease the chance of making type II errors when making inferences about situations; that is, failing to recognize a causal relationship when there is one, which may translate to a lost opportunity or undetected threat in the immediate environment (Abbot & Sherratt, 2011). Beck and Forstmeier (2007) also link this over-attribution of causation to active pattern seeking mechanisms and further suggest that the desire to explain these assumed causes may lead to the fanciful confabulations that become the memetic instantiations of the superstitions that are passed on as belief statements. So, already a possible move from simple cognition to supernatural meme has been outlined. Another effect that is closely related to the over-attribution of causation in avoidance of type II error is the 'hyperactive agent-detection device (HADD)' (Guthrie, 1980; as cited by Barrett, 2000). The proposition of the HADD stemmed from the observation that, when operating in a state of incomplete information, people will tend to attribute intentional agency to otherwise unexplained phenomenon happening around them. This refers directly to the use of the type II error avoidance technique of over-attribution of causation in order to avoid possible predatory threats in the immediate environment; humans were, after all, a prey species for most of our evolutionary past. Assuming that the sound in the bushes is a predator rather than the wind or settling of branches will result in much more cautious behavior overall, a feature that is obviously adaptive in avoiding predation. This mechanism may, however, be over-attributed to other less-than-readily-explainable phenomenon, making for an evolved propensity to see intentional agency in many mysterious happenings in the environment. Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION The propensity to see intentional agency in phenomenon or objects whose agenticity is objectively questionable can be referred to as anthropomorphism. Anthropomorphism is a very common ingredient in many supernatural and religious beliefs. Anthropomorphism requires the ability to infer agenticity in others, an ability known as theory of mind. Theory of mind allows humans to imbue others with agenticity and approximate their specific mental states, an ability that has been undoubtedly advantageous when navigating the social realms inherent in human society. Machiavellian intelligence, or social intelligence, starts with this ability to conceptualize and recognize social interaction, and being able to practice these social interactions on non-social objects through anthropomorphism could have proven a strong advantage for those capable of it. This may have made anthropomorphism a vital tool for honing one's social intuitions, making it an evolutionarily advantageous trait primed for propagation. Another advantageous trait is general pattern recognition ability. Many animals have evolved the ability to recognize the changing of seasons because of its direct influence on the availability and location of food and other resources. Humans undoubtedly recognized the passing of seasons as well as many other regular astronomical happenings; however, the changing of seasons and astronomical events are not exactly readily-explainable phenomenon, maybe explaining why so much myth, mysticism and tradition revolve(s/d) around these events. People's need to explain these patterns may have led to the formation of elaborate stories, myths and legends in order to provide an explanation. These explanations also often introduce an element of possible control of these happenings by the people themselves through ritual or sacrifice. Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION Religion as Culturally Memetic According to Rossano (2006), “ecstatic rituals used to facilitate social bonding,” may have been one of the first forms of religion, emerging during the pre-Upper Paleolithic era (p. 346). It makes sense that rituals or religions that involve social cohesion would be popular, given our very social nature and the sheer logistics of it all; very private beliefs tend to go the grave with those who hold them, whereas socially compatible beliefs enjoy a tremendous transmission advantage and are often widely disseminated. These rituals also often involved hallucinogenic and psychotropic drugs that would both enhance the spiritual quality of the experiences and aid in group cohesion by promoting the release of brain opiates (Frecska & Kulcsar, 1989; as cited in Rossano, 2006). Another socially salient function religion plays in societies is to create a group of people with a shared vision of the world, a vision that most often sets them apart from the rest of the world as being special in some way. This creates very stark lines of ‘in-group’ and ‘out-group.’ Those within the faith view themselves as united. The religions that foster this unity and social cohesion best also tend to be the ones that specify a common enemy of all who follow the faith. With a common enemy comes greater unity and social cohesion within the group. While this tends to benefit the followers by creating a strong social support structure, it also has the effect of creating an explicit, institutionally defined discord between two large groups of people; these are the things war is made of, and may prove detrimental in the long run. Similar to creating a common enemy and with a coinciding time of emergence, during the pre-Upper Paleolithic era, is the act of moralistic aggression and the subsequent social cooperation by way of social scrutiny; that is, the punishment of perceived cheaters by a group of people who are in agreement that the social contract has been breached in some way (Rossano, Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION 2007). Rossano does not see the coincidence of moral aggression and social scrutiny with the emergence of the first forms of religion as a mere coincidence; rather he argues that, “these traits represent a ‘supernaturalizing’ of social scrutiny which helped tip the balance away from individualism and toward community” (p. 3). He goes on to assert that by instantiating a policy of supernatural-policing, our ancestors found a way to externalized an ever-vigilant, omniscient super-ego in order to encourage cooperation and group cohesion through a shared sense of morality and social code of ethics. This Rossano sees as a large part of the move away from individualistic living strategies towards a more egalitarian society, this being a hugely advantageous adaptation for the species as a whole (p. 3). Earlier in this paper it was posited that superstition tends to be a reaction to situations where there is less than optimal information, but yet another instigation of superstition may be a lack of control over a situation. Superstition is often seen when the odds are against the possibility of success, as can be seen in gambling and sports such as baseball; when going up to bat, players tend to become very superstitious and will do anything that they feel might help their odds of success; however, when going out to field the ball, the same players may be completely fine without their superstitious rituals. This could be because the odds are so stacked against them when hitting, and so much in their favor when fielding. The same instigation of superstitious behavior can be seen in the second stage of the evolution of religion (Upper-Paleolithic era) which Rossano (2006) notes as being, “marked by the emergence of shamanistic healing rituals” (p. 346). When faced with illness, our ancestors had little in the way of medicine and therefore little control over the situation compared to today’s technologies. In these types of situations, humans tend to become very superstitious and will try anything they think might help. During this stage of religious evolution, shaman or Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION medicine men offer the only possibility of control over such situations and therefore become very important parts of their societies. It is during this time that we see some transition from egalitarian to transegalitarian hunter-gatherers (p. 346). Ever since humans have lived in groups, there have been leaders and subordinates. In such cases, it could be said that certain religious concepts may become very useful for the leaders. Any ritual that promises some element of control over other-wise uncontrollable circumstances, like the weather, creates the illusion that the leaders who oversee the rituals are in charge. But, the leaders get the best of both worlds in this situation since they have the illusion of control and yet when things don't go their way, they can easily point the finger at the people of the group/tribe; they can claim that it is the lack of faith or sacrifice of the people that is angering the gods and causing them such dismay. So leaders are granted the illusion of power over things they do not control, while maintaining the option of redirecting responsibility back at the group when things don't go well. This is a very good reason for leaders to encourage ritualistic belief structures. The third stage of religious evolution (Upper-Paleolithic era), according to Rossano (2006), “the cave art, elaborate burials, and other artifacts associated with the UP represent the first evidence of ancestor worship and the emergence of theological narratives of the supernatural.” Ancestor worship/honoring is a rather ubiquitous trend amongst world religions. This may go back to the human mind’s propensity for anthropomorphism; or, perhaps it points to the possibility of social-subconscious recognition of the importance of learning from those who lived before you. The wisdom of elders has been important to societies for thousands of years, perhaps ancestor worship and communication is simply an extension of this general psychosocial pattern. Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION Theological narratives of the supernatural that are constructed to explain observed patterns, or anything that is not readily-explainable, become memes. As memes, these various explanations of the world are then subject to selection based on the cognitive predispositions of those considering them. Boyer (2003) outlined the various features that determine the transmission advantage a religious or supernatural concept (meme) will have. Boyer observes that supernatural concepts tend to be a combination of everyday concepts with features that otherwise violate the norms for that concept's 'domain' or type. Boyer uses the concept of a talking tree to demonstrate a straight-forward case of adding features that violate the original concept's archetypical domain (p. 119). Barrett (2000), while citing an earlier paper by Boyer (2000), identifies three domains of knowledge in which these violations can occur: psychology, biology, and physics; along with five ontological categories with which these violations can be made: people, animals, plants, artifacts, and natural, non-living things (p. 31). Barrett (2000) notes that, “the vast majority of supernatural concepts that become part of cultural knowledge,” can be represented as combinations of these three knowledge domains with the five ontological categories; a three by five matrix of the supernatural (p. 31). Boyer (2000) also noted that concepts that commit these violations are more memorable and therefore enjoy a memetic transmission advantage over concepts in which there is no violation of assumptions; however, if they are too counterintuitive, they may be reduced to a less counterintuitive version during on-line processing in order to reason with them as would be done with normal concepts (Barrett, 1998; Barrett & Keil, 1996; as cited in Barret, 2000). So, it appears that counterintuitive concepts that are “minimally counterintuitive” are both most memorable and most useful during on-line processing (Barrett, 2000, p. 30). Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION Barrett also notes, while citing Boyer (2000) that the most common religious concepts to come out of this matrix are intentional agents of some kind. This seems highly relevant to ancestor worship and, again, seems to refer back to the HADD covered earlier. The more successful religious concepts are the ones that satisfy our innate tendencies to see intentional agency in our surroundings; so the HADD, as an evolved cognitive mechanism, has become a selection pressure against which supernatural and religious memes are tested. One way the HADD may contribute to the memorability and transmission advantages of religious concepts that include intentional agency is by way of confirmation bias. Confirmation bias occurs when evidence for a certain proposition is skewed in favor of the proposition by over-emphasizing supporting evidence and down-playing evidence against it. In the case of supernatural agency, the HADD would serve to emphasize the possibility of agency at any given time, therefore reinforcing the apparent probability of the proposition. Another instance of confirmation bias common in religion is regarding the effectiveness of rituals or prayers. Those who truly believe that their rituals and prayers will be answered by attentive supernatural beings will often see evidence of these answers even if none is present. Sometimes the logic is loaded so that no matter what happens, it can be considered an answer; the bumper-sticker-esque saying, “God answers all prayers, just sometimes the answer is 'No',” is an example of creating a bulletproof logic that cannot be debunked. But, as pointed out by Boyer (2003), “There are many irrefutable statements that no-one believes; what makes some of them plausible to some people is what we need to explain” (p. 120). Conclusion It should be clear from this paper that, like other social institutions, religion evolved to meet the psychosocial needs of those involved and as such reflects these needs in its Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION composition. By further evaluating the structure of religion, it may be possible to gain more insight into the cognitive mechanisms that underpin the basic propensities for supernatural thought and the formation of religions as both personal belief systems and social institutions. In closing, I find it necessary to point out the divine irony (pun intended) that the modern religions that so staunchly deny evolution owe their very existence to evolutionary processes; although I suppose anyone who denies evolution is thrust into the same state of irony, but I digress. Running Head: COG SCI OF RELIGION References Abbot, K. R. and Sherratt, T. N. (2011). The evolution of superstition through optimal use of incomplete information. Animal Behavior, Vol. 82(1), 85-92. Barrett, J. L. (2000). Exploring the natural foundations of religion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Vol. 4(1), 29-34. Beck, J. and Forstmeier, W. (2007). Superstition and belief as inevitable by-products of an adaptive learning strategy. Human Nature, Vol. 18(1), 35-46. Boyer, P. (2000). Evolution of a modern mind and the origins of culture: religious concepts as a limiting case. In Evolution and the Human Mind: Modularity, Language and MetaCognition (Carruthers, P. and Chamberlain, A., eds), Cambridge University Press (in press) Boyer, P. (2003). Religious thought and behaviour as by-products of brain function. Trends in Cognitive Science, Vol. 7(3), 119-124. Dawkins, R. (1976). The Selfish Gene. New York City: Oxford University Press. Frecska, E., & Kulscar, Z. (1989). Social bonding in the modulation of the physiology of ritual dance. Ethos, 17, 70–87. Geertz, A. W. and Markusson, G. I. (2010). Religion is natural, atheism is not: On why everybody is both right and wrong. Religion, Vol. 40, 152-165. Guthrie, S. (1980). A cognitive theory of religion. Current Anthropology, Vol. 21, 181–203. Rossano, M. J. (2006). The Religious Mind and the Evolution of Religion. Review of General Psychology, Vol. 10(4), 346-364. Rossano, M. J. (2007). Supernaturalizing Social Life: Religion and the Evolution of Human Cooperation. Human Nature, Vol. 18(3),272-294.