A Specific Aims

advertisement

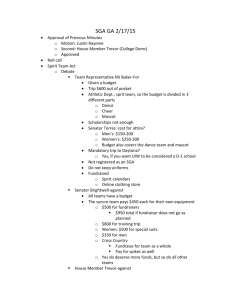

WRITING THE SPECIFIC AIMS PAGE OF YOUR NIH GRANT APPLICATION 2. Specific aims One of the most common edits I make on this section is to slash away at two paragraphs of background on the topic that authors put at the very beginning, and instead frame the topic from the point of view of the proposal as a whole, the big picture. The most important background information can still be included, but you convey to the reader that you have full command of your project if you give the background within the context the proposal. Paragraph 1 The long-term goal of our research is to…. [Then 3 or 4 sentences that give the background necessary to justify this longterm goal.] Paragraph 2 The objective of this application is… [Then a few sentences that give the background necessary to justify this objective., including one that starts, “ The rationale is ….”] Paragraph 3. The central hypothesis is….. Our specific aims are 1. To…. 2. To… 3. To… (Remember, the aims should be related but not interdependent. Also, they should be specific, as measurable as possible, and have a clear goal. Often authors will include sub-hypotheses under each of the aims.) Figure 1. A graphical representation of the aims and how they address the objective of the application (doesn’t have to be fancy; words inside of arrows will do). This should appear at the bottom or bottom-right or bottom-left. Paragraph 4. This work is innovative in that…. (or other things that set this work apart from the other applications). The investigators are particularly well-suited to do this work because…. Paragraph 5 [Impact statement] Successful completion of this project will… [Address mission of institute, health-relatedness, NIH Roadmap; make other benefit statements that would all lead back to your long-term goal] Paul Casella, MFA, Office of Faculty Affairs and Development, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine paul-casella@uiowa.edu Page 1 Restructured Research Plan (Section 5.5) (applications for 2010 funding) 1. Introduction to Application (Resubmission or Revision Applications only) —1 page 2. Specific Aims—1 page 3. Research Strategy—6 or 12 pages a. Significance b. Innovation c. Approach Preliminary Studies for New Applications Progress Report for Renewal/Revision Applications A review of the format changes effective for all applications submitted for 2010 funding: Current Research Plan Restructured Research Plan (Section 5.5) (Section 5.5) 1.Introduction to Application (Resubmission or Revision 1. Introduction to Application (Resubmission or Revision Applications only) Applications only) 2. Specific Aims 2. Specific Aims 3. Background and Significance 3. Research Strategy 4. Preliminary Studies/Progress Report a. Significance b. Innovation 5. Research Design and Methods c. Approach Preliminary Studies for New Applications Progress Report for Renewal/Revision Applications 6. to 12. 4. to 10. (renumbered) 13. Select Agent Research 11. Select Agent Research (modified) 14. to 17. 12. to 15. (renumbered) Paul Casella, MFA, Office of Faculty Affairs and Development, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine paul-casella@uiowa.edu Page 2 Specific Aims 1 page Will appear verbatim in the o Project Description o Specific Aims o Research strategy, which is organized around the aims May be referenced in o Significance o Innovation The specific aims themselves o Each should be numbered o Each should be specific o Each should have a clear goal o Each should have a hypothesis or hypotheses o Each aim should have a clear outcome Specific aims—line of reasoning Background/gap in knowledge Broad, long-term goal Objective of application Central hypothesis Specific aims Expected outcomes/impact statement How it will fill gap in knowledge Paul Casella, MFA, Office of Faculty Affairs and Development, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine paul-casella@uiowa.edu Page 3 Measuring and mitigating real-world errors in older drivers with cognitive decline (TITLE OK?*) A. Specific Aims The broad goals of this research project are to quantify real-world driving behavior in at-risk older drivers with cognitive decline and to develop preliminary interventions to produce meaningful improvements in older driver safety and mobility. Epidemiologic studies show that older drivers, as a group, are at greatly increased risk for a motor vehicle crash compared to middle-aged drivers and to younger drivers over age 25 years old, particularly because of perceptual, cognitive, and motor decline. Further, some older drivers are unaware of their impairments in attention, memory, and decision-making, leading them to unknowingly expose themselves to excess driving risk caused by their impairments. Adverse outcomes include side-impact collisions at traffic intersections or during traffic entry and merging, rear-end collisions with lead vehicles, and run-off-the-road crashes on curved roads, particularly in adverse weather, lighting, traffic, and roadway settings. We propose that solutions to this urgent safety and mobility problem can be derived through systematic, behavioral measurements of older drivers in naturalistic, real-world settings, taking advantage of technological advances that allow direct assessment of real-world driving behavior, together with algorithms and a taxonomy for classifying driver errors, in drivers at potentially increased risk for a crash due to perceptual, cognitive, and motor decline. Understanding the pattern of errors, and where and when these errors occur, can help in the development of rational licensure recommendations and specific restrictions, as well as in the development of safety interventions that provide individualized feedback on driving errors to older drivers to increase their awareness of driving risks and of behavioral strategies to mitigate those risks. Consequently, our specific aims are to 1. Quantify patterns of real-world driving exposure and safety errors in older drivers who are at increased risk for driving safety errors because of cognitive decline associated with aging, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), or early Alzheimer’s disease (AD). H1a. Older drivers with greater cognitive decline will show greater errors/mile driven. H1b. Older drivers with greater unawareness of their cognitive limitations and driving errors will show greater errors/mile and greater exposure to more difficult driving situations than drivers who are aware. 2. Utilize the real-world driving exposure and safety error outcomes data to advance individualized, evidence-based recommendations for older driver exposure that maximize mobility and minimize risk. H2. Older drivers are at particular risk for safety errors on roads less frequently traveled by the driver, and further from home, on highways and high-density-traffic roads, in low-light conditions (dusk, sunset, night), on curves, and in poor weather conditions. 3. Conduct a randomized trial that uses the individualized, evidence-based recommendations developed in Aim 2 to determine if they maximize older driver safety and quality of life. H3: Drivers randomized to receive the individualized intervention will show greater awareness of driving risks, lower exposure to high-risk situations identified in H2, and fewer errors per mile driven. The results of this naturalistic study of driver behavior and errors in the real world will provide unique, community-based data samples on performance outcomes from unprecedented exposure data on driving in older drivers with differing cognitive abilities. All drivers will be evaluated in detail by using a battery of tests designed to assess cognitive abilities that play a critical role in driving performance, including executive functions, attention, perception, and memory. Real-life driving performance will be studied in detail using modern instrumentation and telemetry packages that can provide direct, detailed, long-term information on driver behavior from a driver’s own vehicle, which each driver will drive over a continuous 6-month period, for a total of 75 driver years of data. This includes comprehensive observations of strategy, vehicle use, drive lengths, route choices, and decisions to drive during inclement weather and in high traffic—information not available from any other source. Safety-critical behaviors committed by the at-risk drivers in the real world will be diagnosed using error detection algorithms and a taxonomy for classifying driver errors. Data obtained will increase the understanding of driving safety errors in aging and cognitively impaired drivers. Results will provide unique information on at-risk driver behavior, including events leading to critical incidents or crashes, relationships between high-frequency/lowseverity and low-frequency/high-severity driver errors, and driver self-monitoring, risk acceptance, and ability to adjust to altered safety contingencies. A better understanding of how driving performance deteriorates in cognitive aging is relevant to the rational development Paul Casella, MFA, Office of Faculty Affairs and Development, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine paul-casella@uiowa.edu Page 4 of policies interventions that could be used to preserve mobility and prevent crashes involving older drivers. The techniques used in the study could be adapted to develop future tools for screening, identifying, advising, alerting, educating, and intervening in drivers with functional impairments due to a variety of medical disorders who are at greater risk for impaired driving due to cognitive dysfunction, lack of insight into their impairment, and lack of compensatory behaviors (e.g., avoidance of driving in risky situations). Fair and accurate means of detecting unsafe older drivers with cognitive impairment will help mitigate the tragedy of motor vehicle crashes caused by these impaired individuals. Positive results (fewer errors/mile) following the individualized, evidence-based recommendations in the older drivers can provide evidence that motivates follow-up clinical trials aimed at improving older driver safety. Paul Casella, MFA, Office of Faculty Affairs and Development, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine paul-casella@uiowa.edu Page 5 A SPECIFIC AIMS The goal of this research is to address specific gaps in knowledge about rural poverty and reproductive outcomes using novel epidemiologic and geographic scientific methods. An explicit outcome of this research will be policy and clinical recommendations for action to address rural reproductive health issues. To speed translation of research into policy and action, we propose an external workgroup comprised of clinical and policy experts to advance research into policy and practice. This project will support retention of the most innovative faculty and staff and provide critical financial support to our best graduate students. It will further promote all students’ education by fostering creation of new, cross-departmental graduate courses in spatial and social epidemiology. The rationale is that accumulating evidence shows that living in a low-income community is associated with adverse maternal and infant outcomes—including preeclampsia, infection, preterm delivery (PTD), small-for-gestational age (SGA) delivery, and infant death—even after careful control for known maternal risk factors. However, most studies have focused on low-income, inner-city neighborhoods. Thus, important questions remain about the effect of living in a socioeconomically deprived, rural community. In the US, both urban and rural areas contain pockets of poverty, crime, and substandard housing. In addition to these common factors, rural communities face unique challenges: more persistent and deeper poverty than in urban areas; geographic and structural barriers to services (e.g., poor roads); and exposure to agricultural and waterborne chemicals and zoonotic disease. While all of these factors may contribute to maternal and infant outcomes, current research has not comprehensively studied these factors, nor have scholars incorporated well-constructed indices to study rural socioeconomic deprivation, environmental exposures, or the ruralurban continuum. The objective of this application is to investigate whether living in a socioeconomically deprived, rural community is associated with increased risk of the specific reproductive outcomes of PTD, SGA, and preeclampsia. Our central hypothesis is that women living in socioeconomically deprived, rural communities are at an increased risk of these outcomes over and above established maternal biologic, behavioral, and psychosocial risk factors. To accomplish this objective, we propose integrating geographic and epidemiologic research methods to conceptualize the rural–urban continuum and analyze the impact of individual, community socioeconomic, and environmental data on risk of these adverse reproductive outcomes. Primary data sources include (1) two large, population-based, case-control, NIH-funded studies of reproductive outcomes in Iowa that include individual addresses and extensive health, lifestyle, and demographic data, including personal and household income, education, and occupation; (2) US Census data; (3) countylevel administrative data (e.g., drug-related arrests, health services); and (4) the Iowa Natural Resources Geographic Information System (NRGIS) data repository (e.g., locations of concentrated animal feeding operations [CAFOs]). Specific aims: Aim 1: To construct a geospatial database populated with geocoded maternal and infant health, local population density, Census, county, and environmental/land use data to support comprehensive epidemiologic study of individual, community socioeconomic, and environmental risk factors for PTD, SGA, and preeclampsia. Aim 2: To examine the geographic distribution of reproductive outcomes in relation to both individual and community risk factors as characterized by indicators of community socioeconomic deprivation, position on the rural–urban continuum, the built environment, and the spatial distribution of environmental risk factors (e.g., agricultural land use, CAFOs). Hypothesis: Local rates of PTD, SGA, and preeclampsia can be predicted using a multi-level model to identify community socioeconomic and environmental factors over and above individual risk factors associated with PTD, SGA, and preeclampsia. Approach: We propose to simultaneously analyze effects of maternal, community, socioeconomic, and environmental risk factors on PTD, SGA, and preeclampsia within the context of models that allow for spatial similarity, such as spatial autoregressive models and linear mixed models with random effects for three nested levels of geography (i.e., individuals [1] living within Census Tracts [2] located within counties [3])." Aim 3: To translate our research findings into policy changes (e.g., improved public transportation, prenatal home visits for high-risk women) that might modify the effect of those individual and community conditions found to be associated with heightened risk of adverse reproductive outcomes in the rural Midwest. A. Specific Aims (before) Epidemiological evidence suggests that women exposed to community deprivation, defined by such indicators as poor housing, poverty, and unemployment, are at increased risk for adverse perinatal outcomes, even after controlling for established maternal risk factors. Community deprivation has been linked to birth outcomes through the mechanism of maternal exposure to stress which triggers specific biological responses and can result in poor fetal growth and either indicated or spontaneous PTB. In the US, PTB is a leading cause of infant death and a major contributor to infant and childhood morbidity. Paul Casella, MFA, Office of Faculty Affairs and Development, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine paul-casella@uiowa.edu Page 6 To date, existing epidemiological research on community environment and perinatal health has focused mainly on lowincome urban communities with most studies using low birthweight (LBW) as the outcome of interest. Moreover, the majority of these studies have neither measured nor accounted for the multiple forms of psychosocial stress that may exist at the individual level (life events, work demands, domestic violence) which may alter the effect of exposure to such community-related stressors as poverty and violence. Recognizing these limitations in the literature, the Institute of Medicine recently called for new studies to investigate the relationships between community context and PTB and to consider multiple domains of psychosocial stress, including occupational stress, home and work activity, and domestic violence. This investigator proposes to study the association between living in a deprived non-urban setting and two outcomes which are considered to be more etiologically specific than LBW: preterm birth (PTB) and small-for-gestational age (SGA). This analysis of data from the Iowa Health in Pregnancy Study (NIH/NICHD1R01-HD39753) includes multiple measures of maternal stress, including pregnancy-specific distress, life events, state anxiety, and chronic perceived strain. Community deprivation will be measured using an existing neighborhood deprivation scale, modified to better reflect deprivation in a nonurban setting. Multilevel logistic regression will be used to model risk for PTB and SGA in a two-level hierarchical structure (i.e., individuals nested within communities) to simultaneously study the effects of individual- and community-level exposures on PTB and SGA. Figure 1. Conceptual Model The central hypothesis is that community deprivation in a non-urban setting intensifies the effect of existing maternal risk factors for PTB and SGA. Specific Aim #1: To assess the psychometric validity of a published community deprivation index in this study setting and, retaining elements predictive of perinatal outcomes, construct and validate a new index of community deprivation appropriate for use in non-urban settings. Hypothesis #1: The predictive value of the existing community deprivation index will be increased and the resulting index will provide greater sensitivity by better reflecting salient aspects of the non-urban residential environment. Specific Aim #2: To identify the direct and indirect effects of community deprivation on PTB and SGA and to assess the potential for effect modification between individual psychosocial risk factors and community deprivation on risk of preterm and SGA deliveries. Hypothesis #2a: Community-level deprivation is associated with an increased risk for PTB and for SGA, even after controlling for individual-level risk factors. Hypothesis #2b: Community-level deprivation modifies the relationship between individual-level risk factors and risk of PTB and SGA such that community deprivation intensifies the deleterious effect of established maternal risk factors on risk of PTB and SGA. For example, among women at risk due to young maternal age and exposure to high levels of stress, those living in deprived communities will have a higher risk of PTB than similar women living in less deprived communities. The long-term goal of this research is to elucidate and specify pathways linking communities and individual exposures such as chronic stress and domestic violence to perinatal outcomes. Paul Casella, MFA, Office of Faculty Affairs and Development, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine paul-casella@uiowa.edu Page 7 A. SPECIFIC AIMS (after) The long-term goal of this research is to elucidate and specify pathways linking residential environment to perinatal outcomes. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has called for new studies to investigate the relationships between community context and preterm birth (PTB) and also to consider the role of psychosocial stress, including occupational stress, home and work activity, and domestic violence. The IOM also called for researchers to study outcomes that are more precise than low birthweight, such as gestational age and weight for gestational age, to better assess degree of infant maturity. In the US, PTB is a leading cause of infant death and a major contributor to infant and childhood morbidity. Epidemiological evidence suggests that women exposed to community deprivation, defined by such indicators as poor housing, poverty, and unemployment, are at increased risk for adverse perinatal outcomes, even after controlling for established maternal risk factors. Community deprivation has been linked to birth outcomes through the mechanism of maternal exposure to stress which triggers specific biological responses and may result in poor fetal growth and either indicated or spontaneous PTB. The objective of this application is to investigate this issue in a non-urban setting with PTB and small-for-gestational age (SGA) as the primary outcomes of interest. To date, existing epidemiological research on community environment and perinatal health has focused mainly on low-income, urban communities, with most studies using low birthweight as the outcome. Moreover, the majority of these studies have neither measured nor accounted for the multiple forms of psychosocial stress measured at the individual level, such as life events, occupational stress, and domestic violence. This investigator proposes to study the association between living in a deprived non-urban setting and perinatal outcomes, accounting for maternal psychosocial stress. The central hypothesis is that community deprivation in a nonurban setting intensifies the effect of existing maternal psychosocial risk factors for PTB and SGA. Specific Aim 1: To identify the direct and indirect effects of community deprivation on PTB and to assess the potential for effect modification between individual psychosocial risk factors and community deprivation on risk of PTB. Hypothesis 1a: Community-level deprivation is associated with an increased risk for PTB, even after controlling for individual-level risk factors. Hypothesis 1b: Community-level deprivation modifies the relationship between individual-level risk factors and risk of PTB such that community deprivation intensifies the deleterious effect of established maternal risk factors on risk of PTB. For example, among women at risk due to high levels of psychosocial stress, those living in deprived communities will have a higher risk of PTB than similar women living in less deprived communities. Specific Aim 2: To identify the direct and indirect effects of community deprivation on SGA and to assess the potential for effect modification between individual psychosocial risk factors and community deprivation on risk of SGA. Hypothesis 2a: Community-level deprivation is associated with an increased risk for SGA, even after controlling for individual-level risk factors. Hypothesis 2b: Community-level deprivation modifies the relationship between individual-level risk factors and risk of SGA such that community deprivation intensifies the deleterious effect of established maternal risk factors on risk of SGA. For example, among women at risk due to exposure to high levels of psychosocial stress, those living in deprived communities will have a higher risk of SGA than similar women living in less deprived communities. This study will analyze data from the Iowa Health in Pregnancy Study (NIH/NICHD1R01-HD39753), which is unique in that it includes multiple measures of maternal stress, including pregnancy-specific distress, life events, state anxiety, and chronic perceived strain, along with established risk factors for PTB and SGA. Records include mothers’ address as given on the birth certificate, thus allowing geocoding and use of community-level variables to assess deprivation. Multilevel logistic regression will be used to model risk for PTB and SGA in a two-level, hierarchical structure (i.e., individuals nested within communities) to simultaneously study the effects of individual- and community-level exposures on PTB and SGA. Paul Casella, MFA, Office of Faculty Affairs and Development, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine paul-casella@uiowa.edu Page 8 A. SPECIFIC AIMS The long-term goal of this research is to translate new information about the relationships between rural poverty, community, and infant outcomes into evidence-based public health policy that recognizes the role of communities in shaping health and developmental outcomes for women, children, and families. Rationale. A growing body of scholarship shows that living in a poor community is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, including low birthweight and infant death. However, these findings are based mainly on studies of inner-city neighborhoods. Important questions remain about the effect of living in a socioeconomically deprived rural community. In the United States, many rural areas are characterized by persistent poverty, substandard housing, high rates of drug and alcohol abuse, and uneven access to health and social services. All of these factors may contribute to reproductive health and infant outcomes. The objective of this application is to investigate whether living in a socioeconomically deprived rural community is associated with increased risk of the specific outcomes of preterm delivery (PTD) and small for gestational age (SGA). Our central hypothesis is that exposure to the stressors of living in a poor rural community (e.g., lack of services, inadequate housing) predisposes women to an increased risk of PTD and SGA over and above established maternal biologic, behavioral, and psychosocial risk factors. To accomplish this objective, we propose to combine geographic and epidemiologic research methods. Primary data sources are the Census and the Iowa Health in Pregnancy Study (IHIPS), a population-based study of pregnancies in four Iowa counties. Iowa is an optimal location for this study because it has very rural, poor communities as well as prosperous farming communities and both poor and middle-income small urban and peri-urban neighborhoods (Figure 1). Specific aims follow: Figure 2. Rurality and Poverty in Black Hawk County, Iowa Aim 1: To determine spatial patterns of PTD and SGA and to test for associations between the spatial distribution of PTD and SGA and indicators of community deprivation. Hypothesis: PTD and SGA are non-randomly patterned; there is a statistically significant association between the spatial distribution of PTD and SGA and community deprivation. Approach: The K-function statistic will be used to assess the degree to which there is spatial dependence in the data and a spatial regression model will be used to determine how rurality and community poverty are associated with PTD and SGA. Aim 2: To identify the direct and indirect effects of community deprivation on PTD and SGA and to assess the potential for effect modification between individual risk factors and community deprivation on risk of PTD and SGA. Hypothesis 2a: Residence in a socioeconomically disadvantaged rural community is associated with an increased risk for PTD and SGA, even after controlling for established individual-level risk factors. Hypothesis 2b: Community-level deprivation modifies the relationship between individual-level risk factors and risk of PTD and SGA such that community deprivation enhances the deleterious effect of existing maternal risk factors on risk of PTD and SGA. Approach: Multilevel logistic regression will be used to model risk for PTD and SGA in a two-level hierarchical structure (i.e., individuals nested within communities) to simultaneously study the effects of individual- and community-level exposures on outcomes while controlling for known individual-level risk factors. This study will build upon a comprehensive population-based case-control study (IHIPS) to ascertain how place of residence – specifically, rural place of residence – impacts perinatal outcomes. The IHIPS data and target area are particularly important because they afford comparison between urban and rural areas. Findings from the proposed study will guide and support the development of new targeted research into specific rural community-of-residence influences on reproductive health. Paul Casella, MFA, Office of Faculty Affairs and Development, University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine paul-casella@uiowa.edu Page 9