The major principles for designing the organization as an

advertisement

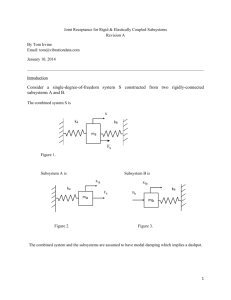

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL BEHAVIOR, 6(4), 501-521 OF ORGANIZATION THEORY AND WINTER 2003 DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATION-PROCESSING SYSTEM: SOME DESIGN PRINCIPLES FROM THE SYSTEMS PARADIGM AND CYBERNETICS Yasin Sankar* ABSTRACT. The major principles for designing the learning organization as an information processing system are derived from systems paradigm, information theory, and cybernetics. The need for these principles is demonstrated by the information pathologies in the classical and contingency design of the organization and information imperatives for designing the organization for the information age. An information processing model that extends the classical and contingency principles for organizational design is developed to provide a new organization model for effective learning. The effectiveness of the learning organization can be partially attributed to the design of the organization as an information processing system. The organization learns, adapts, and responds to innovative change through its information subsystems. INTRODUCTION In the learning organization, everyone is engaged in identifying and solving problems, enabling the organization to continuously experiment, improve, and increase its capability. The essential value of the learning organization is problem solving, in contrast to the traditional organization that was designed for efficiency. In the learning organization, employees engage in problem identification, which means understanding customers’ needs. Employees also solve problems, which mean putting things together in unique ways to meet customer needs. The organization in this way adds value by defining new needs and solving them, which is accomplished more often with ideas and information than with physical products. When physical products are ---------------* Yasin Sankar, Ph.D., is Professor, Faculty of Management, School of Business Administration, Dalhousie University. His research interests are in leadership, ethics, learning organizations, cultural diversity, reengineering of education. SANKAR Copyright © 2003 by PrAcademics Press 502 SANKAR produced, ideas and information still provide the competitive advantage because products are changing to meet new and challenging needs in the environment (Goh & Richards, 1998). Proposition 1: The organizational chart designed by both classical and contingency principles pictures an organization as being structured around the authority and power variables rather than around information processing systems, information flows, and information links so vital to effective decision-making. INFORMATION PATHOLOGIES AND ORGANIZATIONAL DESIGN The Classical Design Proposition 2: The major information pathologies of the classical organizational design are information filtration, distortion, overload and lags in feedback. The major cause of the organizational and information mismatch is the lag between organizational changes and information systems to facilitate them. Authority and power provide the rationale for organizational design in the classical perspective. In the hierarchical structure of the classical organization, the major design parameter is the formal authority at the strategic apex and a chain of command. The classical approach has always provided for routine exchange of information across the chain of command. The coordination of workflow is done by rules, regulations, procedures, and operations manual that regulate the information flow. The coordination of information flow across the organizational units is problematic. The vertical flow of information down the organizational chain of command is imperative. The centralization of authority for decision-making at the strategic apex legitimizes these communications channels. Information filtration in the classical design is a major pathology of the system. Information overload in the organizational hierarchy is a common feature of the system. Information distortion because of bureaucratic codes, symbols, operations manuals and specialized information taxonomies is another pathology of the classical design. Feedback on change initiative at lower levels of the hierarchy is quite limited and with extensive lags. Categorization as a decisionmaking technique is common because of the ritual of categorizing of problems into files, codes, and information taxonomies. The major bureau pathology of the classical design is in the information-processing field. Classical organizational structure can be visualized as a DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATIONPROCESSING SYSTEM 503 formalization of communications channels. The objective of formalization is control over organizational activities by making the patterns of information flow predictable and uniform through prescribed communications channels. Two classical principles, scalar chain and centralization, are the means by which control, predictability, and consistency are maintained (Sankar, 2001). The Contingency Design Proposition 3: The major information pathologies in organizational design are the lack of variety communications networks, and configurations databases. The organizational structure does not information processing systems of the organization. the contingency of information, of distributed conform to the In the contingency design there are some information pathologies but they are not as problematic and dysfunctional as in the classical design. The chain of command, the hierarchical structure of authority is still the predominant mode. To cope with environmental and technological change a high degree of differentiation among organizational units is necessary. To coordinate the workflow among these differentiated units, interdependence must be managed through the information flow. In managing interdependence (pooled, sequential, reciprocal and team) certain integrative mechanisms must be designed. Unlike the classical design which relied heavily on rules, regulations, and manuals as integrative mechanisms, the contingency design uses liaison roles, task teams overlays and integrating units that may cut across the chain of command (Galbraith, 1995). These integrative mechanisms are more flexible for the processing and conversion of information into decision outcomes. However, the decision centers are not necessarily aligned with the communications channels, communications networks or information centers. Power and authority are still the critical criteria that provide the rationale for organizational design rather than information processing and conversion. There are problems in the contingency design of information filtration, information overload, information distortion and lag in feedback on change initiatives. These pathologies are not as severe as in the classical design because of more flexible coordination modes for information flow in the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the organization. However, the organizational design does not enhance the flow of information or optimize the use of a variety of communications 504 SANKAR networks and channels. The processing of information and the conversion of information with a high degree of efficiency is still problematic. Information Imperatives in Organizational Design Proposition 4: The information processing capacity of an organization must match the information-processing requirements of the network of tasks. A variety of integrative mechanisms must be institutionalized within the structural configurations of the organization to enhance the information processing capacity of the organization. The organizational structure of learning organizations has been described in the literature as organic, flat, and decentralized, with a minimum of formalized procedures in the work environment. Some research has supported this finding: organizations with a strong learning capability tend to have low scores on formalization in their organization structure. These research results clearly show a negative relationship between formalization and learning capability (Goh & Richards. 1998). Other researchers have also found that learning organizations generally have fewer controls on employees and have a flat organization structure that places work teams close to the ultimate decision-makers (Miller, 1990). The implication is that the five strategic building blocks can only operate effectively when the organization has a flat, nonhierarchical structure with minimal formalized controls over employee work processes. The limitations of both the classical and contingency design of the organization as an information processing system emphasize the urgency of articulating the information imperatives in organizational design. Four criteria for communications effectiveness are speed, accuracy, variety, and richness. An organizational design must meet these criteria. Speed is essentially the rapid flow of information to decision centers along the vertical and horizontal dimensions of the organization. Accuracy is the minimization of errors in information distortion and information filtration. The information taxonomies within the system must be concise, lucid and logical to facilitate understanding of the information at various levels of the organizational hierarchy. The use of codes, symbols, and jargon must be minimized. Information filtration along the organizational hierarchy must be minimized through a change in the DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATIONPROCESSING SYSTEM 505 organizational culture, its value system, code of ethics, and reward systems. The other important design variable is information richness. Richness pertains to the information-carrying capacity of data (Daft & Lengel, 1998). Information richness is related to the medium or channel through which it is communicated. Some media are richer because they provide richer information to managers. Information richness is important because it relates to the ambiguity of management problems. Rich media provide multiple cues and feedback. Variety as a design variable is also critical for speed and accuracy. When task variety is high, problems are frequent and unpredictable. Uncertainty is greater so the amount of information needed will also be greater. Managers spend more time processing information and they need access to larger databases. When variety is low the amount of information to be processed is low. Some information imperatives are the following: (1) Decision centers must be aligned with the information subsystems. (2) A network structure of control, authority, and information vs. a hierarchical structure is mandatory. (3) A variety of communications networks must be experimented with and instituted in the design. (4) Integrated and distributed databases in a variety of configurations must be linked to the computer systems. (5) Vertical and horizontal linkage mechanisms for coordinating the information flow must be designed. (6) The organization must be designed around the information subsystems, the sensor subsystems, data processing subsystem, decision subsystem, process subsystem, control subsystem and memory subsystem rather than around authority and power. (7) Information is the power variable in organizational design since management is redefined as the processing of information and the conversion of information into decision outcomes. (8) The learning organization must be designed to provide information for strategic change. 506 SANKAR (9) Organizational design is the structuring of task and the structuring of authority to achieve organizational goals. The structuring of task and authority must be aligned through information processing and conversion mechanisms. (10) With change, complexity and uncertainty, the information processing capacity of the organization must be increased through all the information subsystems for effective strategic planning. The Systems Paradigm According to Luthans, despite divergent viewpoints, the systems approach more than any other conceptual approach, has led organizational theorists to take a unified view of the organization as a whole made up of interrelated and interdependent parts (Luthans, 1996). This view of organizations reflects the concept of synergism. The synergistic effect means that the whole organization is greater than the sum of its parts. This is an outgrowth of and is closely related to, the gestalt school of psychological thought. The recent view of organizations as information processing systems facing uncertainty serves as a transition between systems theory and cybernetics information theory. The information processing view makes three major assumptions about organizations. First, organizations are open systems that face external environmental uncertainty and internal, work-related task uncertainty. (Galbraith, 1995, p. 165) defines task uncertainty as “the differences between the amount of information required to perform the task and the amount of information already possessed by the organization.”. The organization must have mechanisms and be structured in order to diagnose and cope with this environmental and task uncertainty. In particular, the organization must be able to gather, interpret, and process appropriate information to reduce the uncertainty. The second assumption is as follows. Given the various sources of uncertainty, a basic function of the organization’s structure is to create the most appropriate configuration of work units as well as linkages between these units to facilitate the effective gathering, processing, and distribution of information. The final major assumption involves the major organizational units of the systems. Because the subunits have different degrees of differentiation, it is necessary to examine the information subsystems, sensor, data processing, decision subsystems, control subsystem and memory subsystem of these subunits. Here we are concerned with the structural mechanisms that will facilitate DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATIONPROCESSING SYSTEM 507 effective coordination among differentiated subunits. yet interdependence Tushman and Nadler (1978) formulate the following propositions about an information processing theory of organizations: 1. The tasks of organizational subunits vary in their degree of uncertainty. 2. As work-related uncertainty increases, so does the need for increased amounts of information, and thus the need for increased information processing capacity. 3. Different organizational structures have different capacities for effective information processing. 4. An organization will be more effective when there is a match between the information processing requirements facing the organization and the information processing capacity of the organization’s structure. 5. If organizations (or subunits) face different conditions over time, more effective units will adapt their structures to meet the changed information processing requirements. INFORMATION PROCESSING PRINCIPLES FOR DESIGN Proposition 6: The systems view of organization takes into account the integrative nature of information flows. The structures of the organization should be designed to facilitate information inputs to decision centers since communications is the process by which organizations change and learn, and adapt to a volatile environment. The systems approach in organizational theory and design has been used as a framework for describing the obvious aspects of an organization such as the functional subsystems of an organization, its input-output-process, the boundary of the system and its degree of interdependence with its environment and among its subsystems. The systems approach has not provided adequate explanation regarding the functioning of the organization nor hypothesis on the nature of systems interdependence or the impact of change and innovation on strategic organizational variables. It has not been applied as an analytical framework to predict the behaviour of the system. The organization as a 508 SANKAR behavioural system exchanges resources, energy, and information with its environment. It tends to maintain itself in a steady state or equilibrium, adopts a feedback process to facilitate adaptation, operates as a cycle of events that become institutionalized and functions in a state of dynamic interaction among its subsystems (Figure 1). Senge (1990) proposes that learning can occur at the individual, team and systemic levels in an organization. The three areas are interrelated and specific organizational systems can be developed to promote learning at all levels. The author suggests that to encourage learning, an organization should generate a holistic view of the organization, acquire and interpret information from the environment, provide only minimum specifications for jobs, facilitate alliance with other organizations and implement systems that retain knowledge (Senge, 1990). The systems paradigm provides such a holistic view to facilitate organizational learning through the information subsystems of the organization. Information is the mechanism through which organizations learn, change, and adapt to a dynamic turbulent environment. The information-processing aspect of the computer has a general analogy in the organizational field. Every organization has the following subsystems: the major design principle may be stated as follows. A strategic change in information input into an organizational system will FIGURE 1 The Information-Processing Subsystems of an Organization Information Change & Innovation Input Look for a right problem Check data with taxonomy Sensor subsystem Data Processing system Control subsystem Make decisions Decision subsystem Memory subsystem Material and energy input Process subsystem DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATIONPROCESSING SYSTEM 509 Recycle Feedback Loop produce changes in the information process system, the sensor, data processing, decision, process and memory subsystem. 1. A sensor subsystem, which is concerned with the reception and recognition of information. 2. A data processing subsystem, which is concerned with breaking down this information into terms and categories which are meaningful and relevant to the system. 3. A decision subsystem, in which decisions are made. Decisions may involve: a. self-regulatory or homeostatic processes b. adaptive or learning processes c. integrative processes 4. A processing subsystem, which ties the whole system together by a set of feedback loops. These loops incorporate the equations of the critical decision variable which, if not respected, lead to lack of growth and the eventual demise of the organism. 5. A memory subsystem, which is concerned with the storage and retrieval of information (Kelly, 1980). CYBERNETIC PRINCIPLES FOR DESIGN Proposition 7: An organization’s decision environment is a major factor in the effective design of its management information system. The pattern of structured - unstructured decisions varies with levels of the organizational hierarchy and so must the information systems of the organization. Since the systems paradigm focuses on the dynamic interrelationship and interaction of entities and subsystems, information, and communication theory are important to the development of systems theory. From a systems theory viewpoint, therefore, an organization can be viewed on one level as a complete integrated decision-making system designed to achieve some specific objective. 510 SANKAR The links between the elements of a system are the communications network within the systems. The state of the link reflects the amount of the information in the system. If the actions of the systems were completely predictable, as in the process of a large digital computer, it would be a complex, deterministic system. Where the relationships are not completely determined, as in the industrial corporation, the system is called complex and probabilistic. The problem of control in complex probabilistic systems is the major focus of cybernetics. The interaction of the system elements on the environment or internal process and systems must be regulated through feedback mechanisms. There can be negative and positive feedback; the negative feedback serves to minimize the distance from the norm, and the positive increases the deviation. The operation of the cybernetic system is chiefly a matter of storing, receiving, transmitting, and modifying information. There is high degree of uncertainty inherent in this operation since the permutations of the system’s data, or fact elements are enormous. The order of the uncertainty in the data, according to Rogers (1987), produce information and the system becomes more controlled and the end-state becomes more controlled and the goal of the system more predictable (Rogers, 1987). A variant of the systems approach is the cybernetics model. Cybernetics as a concept in organizational theory integrates the linking processes in organizational systems and generalizes them to a wide variety of systems. The linking processes are communication, balance, and decisions. It is through them that dynamic and basic interactions are initiated and facilitated in an organization. Decisions, information (communication), and control (balance or regulation) are indispensable elements of complex systems. Stafford Beer notes that “decisions are the events that goes on in the network and they are describable… in terms of the information in the system, and the structuring of communication”(Beer, 1959, p. 175). In this sense, then decisions and information cannot be understood apart from the system’s communication pattern, and this pattern in turn is a reflection of the decisions required and the information necessary upon which to base them. Balance, the third linking process, is introduced in the form of control, or regulation, and this constitutes the heart of the cybernetic processes. Regulation of the system network by the information produced in it is the core of cybernetics. One of the requirements of a cybernetic system is self-regulation. Self-regulation, usually identified as DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATIONPROCESSING SYSTEM 511 feedback, controls current activities by adjusting them after comparing their outcomes or performance against some standard or objective. From the point of view of cybernetics, any large-scale formal social organization is a communications network. It is assumed that these can display learning and innovative behaviour if they process certain necessary facilities (structure) and certain necessary rules of operation (content). First, consider the structure of the system as it might be represented in the language of cybernetics. Any social organization that is to change through learning and innovation, that is, to be ultra-stable must contain (1) certain very specific feedback mechanism, (2) a certain variety of information, and (3) certain kinds of input, channel, storage, and decision-making facilities. This can be stated in the form of an axiomatic proposition: that complexity of purposeful behaviour is a function of the complexity of the communication components or parts of the system. More specifically, every open system behaving purposefully does so by virtue of a flow of factual and operational information through receptors, channels, selectors, feedback loops, and effectors. Every open system whose purposeful behavior is predictive, and this is essential to ultrastability, must also have mechanisms for the selective storage and recall of information: it must have memory. Does the social organization under scrutiny behave purposefully? Does it solve problems? And does it forecast future events? If the answers are in the affirmative, then one must find in it certain kinds of communications, information, and control mechanisms that are conducive to change and technological innovation (Cadwallader, 1985). A cybernetic model would focus the investigator’s attention on information as the critical variable: (1) the quantity and variety of information stored in the system, (2) the structure of the communications network, (3) the pattern of the subsystem within the whole, (4) the number, location, and function of negative feedback loops in the system and the amount of time-lag in them, (5) the nature of the system’s memory facility, (6) the operating rules, or program determining the system’s structure and behaviour. The operating rules of the system and its subsystems are always numerous. Relevant for the present problem are (1) rules of instructions determining range of input, (2) rules responsible for the routing of the 512 SANKAR information through the network, (3) rules about the identification, analysis, and classification of information, (4) priority rules for input, analysis, storage, and output, (5) rules governing the feedback mechanisms and, (6) instructions for storage (Cadwallader, 1985). Chaffee (1980), in reviewing the literature on decision-making, has developed a set of seven criteria for defining the requirements of rational choice processes in terms of the collection and use of information: 1. Information is received prior to the decision’s being made; 2. Information is problem-centered and goal-directed; 3. Information documents the existence of and the need to solve the problem or reach the goal; 4. Information includes consideration of more than one alternative for reaching the goal or solving the problem; 5. Information has logical internal consistency in terms of posited cause-effect relationships; 6. Information is oriented toward maximization, in that it demonstrates the value of the various alternatives considered in reaching the goal; and 7. Information identifies the value premises on which it is based. One final condition could be added, which is that the choice is made to accept those alternatives which, on the basis of the information provided, seem to provide the best likelihood of achieving the goals or solving the problem. INFORMATION, CHANGE, AND INNOVATION (SOME PRINCIPLES) The literature on organizational learning has been elusive in providing practical guidelines or managerial actions that practicing managers can implement to develop a learning organization. Some of the questions raised by managers about the concept of learning organizations are as follows: What is a learning organization? What are the payoffs of becoming a learning organization? What should I do to encourage organizational learning? How do I know if my company is a learning organization? What are the characteristics of a learning organization and how do I sustain one? Is there an implementation strategy? Clearly a DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATIONPROCESSING SYSTEM 513 discussion with a managerial perspective on how to build a learning organization is lacking in the literature. To answer the first and most frequently asked question, “What is a learning organization?” we need a definition. The following definition best reflects the conceptual approach of this paper (Goh & Richards. 1998). Proposition 8: A learning organization is an organization skilled at creating, acquiring and transferring knowledge, information, and at modifying its behaviour to reflect new knowledge and insights (Garvin, 1993). In a learning organization: 1. The rate of innovation is a function of the rules organizing the problem-solving trails (output) the system; [This sentence does not make sense as written] 2. The capacity for innovation cannot exceed the capacity of the information processing systems of the system; 3. The rate of innovation is a function of the quantity and variety of information; 4. A facility, mechanism, or rule for changing organizing patterns of a high probability must be present to facilitate flexibility of processing; 5. The rate of change for the system will increase with an increase in the rate of change of the environment (input). That is, the changes in the variety of the inputs must force changes in the variety of the outputs or the system will fail to achieve ultra-stability. 6. As cybernetics recognizes the need to study interactions of the subsystems in an organization, it focuses on information as the key to analyzing and understanding organizations as learning systems. Consequently, communication theory and information theory were central in the development of cybernetic systems and offer the following principles: 1. Communication is the basic process facilitating the interdependence of the parts of the total system; it is the mechanism of coordination. 514 SANKAR 2. Information processing is the main function performed by all organizations; organizational systems were essentially communication systems. 3. Management in cybernetic language is the processing of information and the conversion of information into decision outcomes 4. The greater the task uncertainty, the greater the need for information processing. 5. The larger the number of elements in the decision-making process such as the number of departments, the greater the informationprocessing requirements of the organization. 6. The greater the degree of interdependence among the elements of decision-making, the greater the information processing. 7. To increase the capacity of the organization to process information, more flexible integrative mechanisms are needed. 8. Task variety, change, and complexity will produce different degrees of uncertainty in the information domain and decisionmaking. 9. The structural configuration of an organization must be designed with information as the design parameter. 10. Different structural configurations are needed for different information domains within a complex organization. The currency of organizational theory is information. As information is infinite in quantity, it is expensive to collect, must be treated selectively, can only be packed up with a taxonomy (classification) based on yesterday’s experience (and thus is to some extent irrelevant), causes surprise (which is how we measure it), and is fraught with uncertainty. AN INFORMATION PROCESSING MODEL The systems and cybernetic concepts of organizations focus on the dynamic interaction and intercommunication among components of the system. Systems theory subordinates the separate units or departments of an organization to decision-making and communications networks. The cybernetic view of organizations is concerned with decisions, control, self-regulation, and feedback operating in dynamic equilibrium. Both DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATIONPROCESSING SYSTEM 515 take into account the integrative nature of information flows. This concept is demonstrated in Figure 1 where each organizational entity is seen as an information system with the components of input, processor and output. Each is connected to the others through information and communication channels and each organizational entity becomes a decision point. Thus the communications process is dynamic, because as the objectives of the organization change, the content of communication must also change in order to alter or reinforce the actions of various segments of the organization. In the language of the systems model and cybernetics, communication is a linking activity of organizations. At a practical level, designing the organization as an information processing system means that the following information subsystems, the sensor subsystem, data processing system, decision subsystem, process subsystem, control subsystem, and memory subsystem may be integrated into each structural configuration within the organization and along levels in the organizational hierarchy. Proposition 9: The organization as a learning system must be designed around the information domain and those parameters of information such as complexity, interdependence, variety, uncertainty, and information subsystems and databases. The application of management information systems (MIS), executive information system (EIS) and decision support systems (DSS) to the right task and types of managerial decisions is essential to the effectiveness of learning organizations. An important aspect of organizational structure is the way in which the parts of an organization communicate and coordinate with one another and with other organizations. Vertical linkages coordinate activities between the top and bottom of the organization, while horizontal linkages are used to coordinate activities across departments. Advances in information technology can reduce the need for middle managers and administrative support staff, resulting in leaner organizations with fewer hierarchical levels. In some organizations, such as Microsoft and Andersen Consulting, front-line employees communicate directly with top managers through e-mail. Information technology can also provide stronger linkages across departments and plays a significant role in the shift to horizontal forms of organizing. Coordination no longer depends on physical proximity; teams of workers from various functions can communicate and collaborate electronically. 516 SANKAR New technology enables the electronic communication of richer, more complex information and removes the barriers of time and distance that have traditionally defined organization structure. A special kind of team, the virtual team, uses computer technology to tie together geographically distant members working toward a common goal (Daft, 2001). At the strategic level of the organization where there is high uncertainty in decision outcomes, objectives, and the means-ends chain more information processing is critical for strategic planning. The sensor subsystem must be activated through a variety of information systems, EIS, SIS (strategic information systems), DSS, and DDB (distributed databases). At the tactical and operational levels of the organizational hierarchy, planning goals and action goals respectively mean that the other information subsystems which use other varieties of information systems and data-bases may be more effective for semi-structured and structured decision-making. At each level, the information mechanisms such as channels, networks, feedback loops and distributed data process (DDP) configurations will vary with the elements of the information domain. At the strategic level the mechanisms will require some degree of flexibility with information channels, networks, and configurations linked to decision centers. At each level of the organization, the strategic, tactical, and operational, the information needs will vary because of the elements of the task and the information domain. Linking information channels and networks to decision centers is more effective than the traditional linkage to power centers. Information emerges as the critical contingency variable in organizational design rather than power and authority. The structural configurations will also vary with the information domain. Organizational decisions vary in complexity and can be categorized as programmed or nonprogrammed (Simon, 1960). Programmed decisions are repetitive and well defined, and procedures exist for resolving the problem. They are well structured because criteria of performance are normally clear, good information is available about Organizational decisions vary in complexity and can be categorized as programmed or nonprogrammed (Simon, 1960). Programmed decisions are repetitive and well defined, and procedures exist for resolving the problem. They are well structured because criteria of performance are normally clear, good information is available about current performance, alternatives are easily specified, and there is DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATIONPROCESSING SYSTEM 517 relative certainty that the chosen alternative will be successful. Examples of programmed decisions include decision rules, such as when FIGURE 2 Decision-Making and Organization Design to replace an office copy machine, when to reimburse managers for travel expenses, or whether an applicant has sufficient qualifications for an assembly-line job. Many companies adopt rules based on experience with programmed decisions. 518 SANKAR Nonprogrammed decisions are novel and poorly defined, and no procedure exists for solving the problem. They are used when an organization has not seen a problem before and may not know how to respond. Clear-cut decision criteria do not exist. Alternatives are fuzzy. There is uncertainty about whether a proposed solution will solve the problem. Typically, few alternatives can be developed for a nonprogrammed decision, so a single solution is custom-tailored to the problem (Daft, 2001). The decision about how to deal with charges of faulty Pentium chips was a nonprogrammed decision. Intel had never faced this kind of problem and had no rules for dealing with it. Many nonprogrammed decisions involve strategic planning, because uncertainty is great and decisions are complex (Pocanowsky, 1995). Particularly complex nonprogrammed decisions have been referred to as “wicked” decisions, because simply defining the problem can turn into a major task. Wicked problems are associated with manager conflicts over objectives and alternatives, rapidly changing circumstances, and unclear linkages among decision elements. Managers dealing with a wicked decision may hit on a solution that merely proves they failed to correctly define the problem to begin with. Today managers and organizations are dealing with a higher percentage of nonprogrammed decisions because of the rapidly changing business environment and globalization. This information contingency model is designed (1) to increase the information processing capacity of the organization (2) to provide flexibility in information systems for coordinating the information flow and workflow (3) to maximize the use of a variety of data bases for information processing (4) to align the conjunction of informationcommunications channel with decision centers (5) to facilitate the use of a variety of communications networks (6) to locus and integrating information subsystems within a modular units of a complex learning organization (7) to speed up the decision making process (8) to apply cybernetic principles of feedback, control, and self regulation to design information systems (9) to focus on the information domain rather than power and authority as the design parameter (10) to assist in the design of adaptive learning organizations in the context of the information domain. DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATIONPROCESSING SYSTEM 519 The information-processing model shifts the emphasis from the contingency design parameters. The optimal degree of differentiation and integration is determined not only by the degree of environmental change but also by the information domain, variety, complexity, change and uncertainty of information. Environmental determinism is still critical but so is the type of information domain that must be designed to cope with environmental change and globalization. With reference to the technological imperative, the organizational structure must cope with technical complexity in the Woodward’s conventional paradigm and with types of interdependence (pooled, sequential, and reciprocal a la Thompson’s menu. Now the structure must also cope with computer technology, integrated vs. distributed data-bases, information taxonomies based on degree of complexity and variety of information inputs, information processing capacity of information subsystems, variety of DDP configurations, interdependence among the information subsystems, feedback loops within structural configurations, elements of task uncertainty and information processing needs and types of information systems. Principles from cybernetics, the systems paradigm, and information theory alluded to earlier, are more relevant and informative as design principles for the learning organization than the conventional paradigms of design. CONCLUSION The importance of this information processing view of organizational design is that it determines the pattern of problems and information needs within the organization. The information support systems and organizational structure should provide information to managers based upon patterns of decisions to be made. When the organization is designed to provide correct amount and type of information to managers, decision processes work well. When information systems are poorly designed, problem solving and decision processes will be ineffective and managers may not be able to solve the problem. The processing of information and the conversion of information into decision outcomes can be effectively facilitated if the structural configuration matches the elements of the information domain or the information needs of the task, its degree of complexity, variety, and change. Information becomes the contingency variable rather than authority and power for the design of modular units within complex 520 SANKAR learning organizations, virtual teams and network systems. Shared information is one of the building blocks of the learning organization. In the move toward information, knowledge and idea based organizations, information sharing reaches extraordinary levels, hence our major focus on the design of the organization as an information processing system. REFERENCES Beer, S. (1959). Cybernetics and management. New York: Willey. Cadwallader, J. (1985). The cybernetics analysis of change in complex organizations. In Litterer, J. (Ed.). Organizational Analysis (pp. 132146). St. Paul, MN: West Publishing. Chaffe, E. (1980). Decision models in university budgeting. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation Stanford University, Palo Alto, California. Daft, R. (2001). Organizational theory and design. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing. Daft, R. L. & Lengel, R. H. (1998). Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Management Science, 32, 554-71. Galbraith, J. (1995). Designing complex organizations. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Garvin, D. (1993, July-August). Building a learning organization. Harvard Business Review, 2, 78-91. Goh, S., & Richards, G. (1998). Bench-making the learning capability of organization. European Management Journal, 2 (2), 575-583. Kelly, J. (1980). Organizational behavior: Its data, first principles and applications. Homewood, IL: Richrad Irwin. Luthans, F. (1996). Organizational behaviour. New York: McGraw Hill. Miller, D. (1990). Organizational configurations: Cohesion, change and prediction. Human Relations, 43, 781-789. Pocanowsky, M. (1995). Team tools for wicked problems. Organizational Dynamics, 23 (3), pp. 167- 175 Rogers, R. (1987). Organizational theory. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. DESIGNING THE LEARNING ORGANIZATION AS AN INFORMATIONPROCESSING SYSTEM 521 Sankar, Y. (2001). A value-based model of organizational design (Working Paper No. 6). Dalhousie University. Canada. Senge, P. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of learning organizations. New York: Doubleday. Simon, H. (1960). The new science of management decision. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Tushman, M., & Nadler, D. (1978, July). Information processing as an integrating concept in organizational design. Academy of Management Review, 20 (2), 158-176).