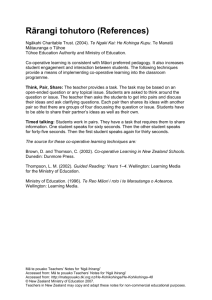

Good practice points

advertisement