ANALYTIC EPIDEMOLOGY

advertisement

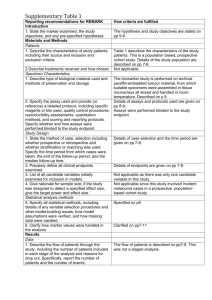

MARK D CURRICULUM FOR THE HEALTH SCIENCES IN SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE Number (unit, topic): U3-T2 Title Author(s), degrees, institution(s) Address for correspondence Keywords Learning objectives Synopsis (Abstract) Teaching methods Specific recommendations for teacher Assessment of students Prior review – Status:D ECTS (suggested): Analytic Epidemiology: The Anatomy of the Epidemiologic Study Biljana Taushanova, MD, specialist in epidemiology Institute of Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine University "Sts. Cyril and Methodius" Skopje, Macedonia Biljana Taushanova, MD Institute of Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine Vodnjanska 31 2000 Skopje, Macedonia Tel. +389 2 114 825 ANALYTIC EPIDEMOLOGY: The Anatomy of the Epidemiologic Study Biljana Taushanova, Institute of Epidemiology, Faculty of Medicine, University "Sts. Cyril and Methodius", Skopje, Macedonia The part of the epidemiology dealing with the investigation of the causes of the diseases (etiology), design of the investigations, scheme of how they will be carried out, belongs to the analytic epidemiology. The analytic epidemiology has its practical application in the prevention of the diseases and in the public health. There are two types of epidemiologic studies: experimental and observational. The major difference between these two is that in an experimental setting, the epidemiologist can specify the conditions under which the study is to be conducted, while in an observational study, he is not able to control these conditions. Briefly, then, the distinction between the experimental and observational epidemiologic studies is whether or not the epidemiologist has control over the assignment of individuals into the study groups. EXPERIMENTAL EPIDEMIOLOGY The experimental epidemiology consists of: Clinical trials, which is the name for clinical investigations carried out in diseased people (patients, cases), Field studies, with healthy people as a study group and Community intervention trials in which the interventions are carried out in healthy subjects. In experiments (clinical trials), the epidemiologist controls the method of assigning subjects to either exposed or non-exposed group. In the process of the study design, it is important to select a sample that is representative for the whole investigated population. A commonly used means of assignment is to randomly allocate similar individuals to the exposed or non-exposed group. This method has the advantage over the systemic and stratified ones. OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES The observational studies can be divided into three categories: o Prospective (“cohort”) studies, o Cross-sectional (“prevalence”) studies and o Retrospective (“case-control”) studies. The prospective study involves selection of individuals based upon exposure to an agent, while the cross-sectional and retrospective studies involve selection based on the presence or absence of the disease. 1 In cohort studies the direction is prospective, from the cause (exposure to an incriminated factor) to the effect (disease). In case-control studies the direction is retrospective, from the effect (disease) to the cause. The distinction between cross-sectional and retrospective studies is that in the former, the exposure or characteristic is current, while in the latter it had occurred at some time in the past. In other words, the cross-sectional studies are most appropriate for short-lasting studies, while the cohort and case-control studies are the methods of choice for longitudinal investigations. EXPERIMENAL EPIDEMOLOGY In cross-sectional and retrospective studies, comparisons are made between a group of persons who have the disease and a group that does not. Usually, those with the disease are called ‘cases” and those without the disease are called “controls”. (For these reason, such studies are generally referred to as “ case-control studies”. Although mainly used for retrospective studies, the term “case-control” can also be applied for prospective studies). Cross-sectional studies have been called “prevalence”studies and retrospective studies have been called “case-history” studies. The Distinction between Retrospective and Prospective Studies Whether the characteristic or factor of interest is (or was) present in the two groups is usually determined by interview and (or) review of records. In both retrospective and cross-sectional studies, the proportion of cases exposed to the agent or possessing the characteristic (or factor) of etiological interest is compared to the corresponding proportion in the control group. If a higher frequency of individuals with the characteristic is formed among the cases than the controls, an association between the disease and the characteristic may be inferred. The experimental studies can be controlled, not controlled experimental studies and natural experiments. 1. Controlled experimental study The epidemiologist prefers the studies in which he (she) can control the method of assigning subjects to either the exposed or non-exposed group. A commonly used means of assignment is to randomly allocate similar individuals to the exposed or non-exposed groups. Such an experimental study is termed “clinical trial” or, better, “randomized clinical trial”. In our example a group of subjects receive the drug, which is under the study, while another group (control) receive a placebo instead, which is of the same appearance and taste as the drug. The assignment to the groups is done randomly. After a certain followup period, the effect of the treatment is evaluated in both groups. A statistically significant difference in their answer suggests a positive or negative effect of the drug. 2. Not controlled experimental study Most of other types of experiments, known as ”community trials”, belong to this type of epidemiological studies. Although the epidemiologist would prefer experimental 2 studies, as he (she) could control the conditions under which the study is carried out, this control is not, however, always feasible. That is case with various vaccines that interfere with the natural course of certain diseases. The efficacy of a vaccine can be evaluated only after many years of its application. 3. Natural experiment Certain natural phenomena occurring in the human population have the characteristics of an experiment. E.g.: each epidemic represents an experiment, which the nature itself has designed. OBSERVATIONAL STUDIES. PROSPECTIVE STUDIES The limitations of inferences derived from retrospective studies make it desirable, in many instances, to confirm any association observed in a retrospective study by means of a prospective one. The general concept of the prospective study is relatively simple, although such studies can be conducted in several ways. A sample of the population, which is generally healthy at the beginning of the study, is selected and information is obtained to determine which person either have a particular characteristic (such as a certain living habit or physiological trait) that is suspected of being related to the development of disease being investigated, or have been exposed to a possible etiological agent. These individuals are then followed for a period of time to observe who develops and/ or dies from the disease. Incidence or death rates for the disease are then calculated, and the rates compared for those with the characteristic of interest and those without it. If the rates are different, an association can be said to exist between the characteristic and the disease. This type of study has been described by a variety of terms: “cohort”, ”incidence”, ”longitudinal”, ”forward-looking” and “follow-up”, The most widely used is “cohort”, though a certain number of authors insist on the distinction between the cohort and prospective study. Prospective studies can be classified as concurrent and nonconcurrent studies. In a concurrent study, those with or without the characteristic or exposure are selected at the start of the study and followed over a number of years by a variety of methods. In a nonconcurrent study, the investigator goes back in time, selects the groups, and then traces them over the time, usually to the present, by a variety of methods. Here is an example of the concurrent prospective study: A prospective cohort study concerning neonatal asphyxia and subsequent mental retardation starts in 1997. The babies born during that year in a certain hospital were divided into those who had suffered from neonatal asphyxia and those who had not. Mental development in children of both groups was assessed 3 years later (in 2000) and will be done again after 5-yr time-span (in 2002), when the final comparisons between the two groups will be made and conclusions drawn as to the existence of an association between neonatal asphyxia and mental retardation. Among many examples of nonconcurrent prospective studies, listed in the textbooks of epidemiology, I will cite the study of the relationship between polycytemia vera, 3 treated by X-rays, and leukemia, which had been clinically observed since 1905. The cohorts of patients with and without radiation treatment, formed in 1947 were traced through December1961, when the major results made it clear that leukemia occurred predominantly in patients who had received some form of radiation. Although the cohort study is generally prospective, it can also be retrospective, when it employs data concerning a previous exposure to the incriminated agent and the previous health conditions of the population under the study. For example, when in our investigation on the relationship between the neonatal asphyxia and mental retardation, mentioned above, it is included a survey, based on the hospital documentation, concerning the incidence of neonatal asphyxia in 1986 and the intellectual function in the asphyxiated children assessed during the school year1995/96. That means that in this so called retrospective cohort study, both the exposure to the risk factor and the consecutive effect to the health of the exposed subjects, had occurred prior to the start of the present investigation. The cohort studies help to compute the relative and absolute (attributable) risk for acquiring a certain disease following the exposure to the risk factor(agent). In the following example, the association has been studied between the exposure of the mothers to rubella during the pregnancy and the malformations (most frequently catarrhact) in their newborn babies as the consequence (disease, effect), Framework for the cohort study. Table 2x2. Rubella in the mother yes no total Malformations in the child yes a c a+c cases no b d b+d controls Total a+b c+d a+b+c+d cases+controls At the start of the investigation, all mothers are healthy. During the pregnancy a certain number of them contract rubella, while the others do not. Those who had rubella are a and b, those who had no rubella are c and d in the above table. In the further procedure we calculate: 1. The frequency of occurrence, that is the incidence rate of the malformations (a) in children of the mothers who had rubella during the pregnancy (a+b): a ______ a + b 4 2. The frequency of occurrence, that is the incidence rate of the malformations (c) in children of the mothers who had no rubella during the pregnancy (c+d): c ______ c + d If the incidence rate of the malformations is higher in cases than in controls a ______ a + b c > ______ c + d we conclude that the malformations in the neonates are causally related to the rubella in the mothers acquired during the pregnancy. The relation a ______ a + b a ( c+ d ) ________________ or ________________ c ______ c(a+b) c + d is called relative risk and it shows how higher is the incidence of congenital malformations in children of the mothers with rubella during the pregnancy than in children with no maternal rubella during pregnancy. It is possible to compute also the absolute (attributable) risk by means of the following formula: a c ______ _ ______ a + b c + d where the incidence of the disease in the exposed subjects is retracted from the incidence of the same disease in the non-exposed persons. The advantage of the cohort studies is that they offer the possibility of computing the incidence, relative and absolute risk. The disadvantages of the method are that the studies are expensive, long-lasting, engage a large number of participants, and they are very inefficient, if not impossible in studying rare diseases. Example for cohort study: The Framingham study. 5 CASE-CONTROL STUDIES To the analytic epidemiology belongs also the method of the anamnestic, so called comparative retrospective study, also termed the case-control study. Contrary to the name, both prospective and retrospective studies can be case-control. The case-control study is characterized by the identification of the two study samples (cases and controls) on the basis of the presence or absence of the outcome factor and by the estimation for both samples of the proportion possessing the antecedent factor under study (the risk factor). The control group should be as similar as possible to the case group in many epidemiological characteristics (age, sex, profession, social status, nationality etc.) and as different as possible in regard to the incriminated (risk) factor. The data for a case-history study are generally tabulated in the form of a fourfold table, as shown below: Framework of a case-control study After the selection of the two groups is made, the proportion of the diseased is computed in the group of the exposed persons: a ______ a+c then in the group of the non-exposed subjects : c ______ a+c which are to be compared to the proportion of the healthy subjects previously exposed to the risk factor: b ______ b +d and the proportion of the healthy subjects not exposed to the risk factor: d ______ b +d if a _____ a+c is statistically different from b _____ b+d 6 a statistical association can be said to exist between the disease and the characteristic (exposure to the risk factor). In our previously cited example, the assumption is that the mothers who gave birth to children with malformation: a ______ a+c had been more exposed to rubella infection during pregnancy, compared to the mothers who gave birth to children with no malformation: b ______ b+d HEALTH DETERIORATION AND PREVENTION OF DISEASES To come to health deterioration and to a disease, it is necessary a simultaneous action of, or better an interaction between the following three factors: the host, the causative agent and the environment, which constitute the so-called ecological trias of Gordon. In the prevention of diseases, beside this trias, the action of other factors should be taken into the account, which makes the occurrence of a disease and deterioration of the health to be multifactorial. The genesis of the health deterioration in an individual and the occurrence of the disease start long before the first signs and symptoms. In this process two periods can be distinguished: - Forpathogenesis and - Pathogenesis itself. In the forpathogenesesis period, an interaction between the ecological trias of Gordon takes place, the consequences of which are felt in the pathogenesis period. The period of pathogenesis can start insidiously or abruptly and take course of either an inapparent form or a manifest disease with typical clinical manifestations. Such a disease ends with a complete recovery or takes a chronic course with lasting consequences (invalidity). Both acute and chronic diseases may end, in the worst case, with death. The prevention has best chances to succeed in the period of forpathogenesis, that means before the action of the causative agent has taken place. 7 There are three (3) levels of prevention: primary, secondary and tertiary, and, in the frame of these 3 levels, there are five (5) stages. A. PRIMARY PREVENTION This level includes the first two stages of prevention: I. Promoting health II. Specific protection III. Promoting (improving) health (First stage) The measures of this stage of prevention are not aimed at a particular disease, but their implementation creates the conditions, which are necessary for the prevention of all diseases and for carrying out studies concerning the health of a given population. In fact these are the measures of a popular health education and of an environmental control. I.1. The health promoting programs which are aimed at as a large population as possible, virtually at the whole population of a country, promote the health by teaching on how to avoid the risk factors for diseases and, in case of the disease, how to recognize the early signs and symptoms and to ask for a professional help as early as possible. I.2. The measures included in this subsection reflect the efforts made on the part of the society to create conditions of a healthy living and working environment, in the context of the World Health Organization definition of health as a complete physical and psychological well-being. IV. Specific protection (Second stage) It consists of measures undertaken in order to prevent certain diseases, either contagious or chronic non-contagious ones. As to the contagious diseases, these measures can be directed at the causative agent, the host or the environment separately, although, most frequently, they are aimed at all three factors of the ecological trias of Gordon. II.1. Specific protection regards the environment Here belong the measures, which constitute regular components and make general rules of the communal hygiene, such as: Supply of hygienically safe water, Sanitary disposal of the fecal materials and waste waters, Sanitary control of the communal surfaces (streets, squares) and objects (marketplaces, bus /and railways stations), public swimming pools etc., Sanitary control during the process of construction of both the living quarters and industrial objects, Control of sanitary and accommodation facilities in objects with massive attendance, such as the kindergartens, schools, shelters for old and homeless 8 people, military barracks, hospitals and institutions, carantine objects and refugees camps. Sanitary control of food products (meat, milk and others) from the production site to the consumer, as well as of the personnel manipulating with them. II.2. Specific protection regards the agent Avoiding the noice, radiation, air pollution ( e.g. measures aimed at diminishing the ammount of the exhausted gasses from the motor vehicles), contact with toxic materials etc. II.3. Specific protection regards the man Giving vitamins in order to prevent avitaminosis, Iodation of the salt to prevent hypothyroidism, Vaccination to prevent certain contagious diseases, Seroprophylaxis (passive immunization), Chemioprophylaxis ( esp. in the prevention of tuberculosis), Depistage ( discovery ) and control of the carriers (both acute and chronic) of the agents of the contagious diseases, such as typhoid fever, paratyhoid fever A and B, type B viral hepatitis and HIV/AIDS. B. SECONDARY PREVENTION (Second level) The measures belonging to this level of prevention apply during the phase of pathogenesis. They represent the third stage(III) of prevention ( out of the total of five), according to the scheme given in the introduction of the chapter on prevention. The measures of this stage of prevention are aimed at the Early diagnosis and adequate treatment of the disease Their purpose is to make the disease, which is already manifest, to take a benign course and leave as little consequences (damages) as possible. To give these measures chance for success, the accurate diagnosis should be made and the adequate treatment started as early as possible. If these conditions are not met, the risk is great that the disease becomes chronic, or, in the worst case, ends with death of the patient. C. TERTIARY PREVENTION (Third level) This level includes the forth and the fifth stages of the prevention and they are the following: IV. Attenuating (Improving) the patient’s incapacity and invalidity and V. Medical rehabilitation. 9 IV. Attenuating (Improving) the patient’s incapacity and invalidity The measures of this stage of prevention apply when the development of the disease has reached an advanced stage or it has already left its sequelae. They consist of physiotherapeutic measures. Physiotherapy uses different physical factors for improving the function of the parts of the body damaged by the disease (water, light, caloric, electrical and mechanical energy). V. Medical rehabilitation. The medical rehabilitation has a more difficult task than the physiotherapy. It tries to rehabilitate the diseased person and enable him (her) to resume his (her) previous work. Along with the medical rehabilitation, the aim of the measures of this stage of prevention is to achieve a social and professional rehabilitation as well. In case these maximalistic goals cannot be achieved, one should be satisfied with the minimum, provided the patient is enabled to take care of himself, that means to be able to feed himself, to dress himself and to satisfy his physiological needs without help of a third person. 10