powerpoint - Montana State University Billings

Practically perfect in every way: communication strategies of ideal relational

partners. Susan M. Wildermuth, Sally Vogl-Bauer and Julimar Rivera.

Communication Studies 57.3 (Sept 2006): p239(19).

19 PDF pages | About this publication | How to Cite | Source Citation |

Spanish

Subjects

Abstract:

This study utilized social exchange constructs to examine communication strategies used by self-defined ideal relational partners when initiating dating relationships. Two hundred forty-four participants generated 1183 communication strategies they would use to initiate relationships if they believed themselves to be ideal partners. A content analysis revealed 15 categories of communication strategies enacted by ideal relational partners. These categories included initiation, emotional disclosure, direct inquiry, impression management, shared activities, supportive behaviors, information gathering, gift giving, compliments, other-initiated behaviors, assistance from others, selfacceptance, pickup lines, bragging, and use of humor. Implications for interpersonal communication research are discussed.

Keywords: Social Exchange; Dating; Ideal Relational Partners; Communication

Strategies

Full Text : COPYRIGHT 2006 Central States Communication Association

Reality-dating shows currently proliferate television programming. From Joe Millionaire to The Bachelor, these programs show real-life men and women competing for the attention, affection, or hand in marriage of one member of the opposite sex. Realitydating programs create situations where one person is the sought-after "ideal" relational partner who has extensive control over the progression of the dating relationship and unilateral power to determine if the relationship succeeds or fails. Essentially, realitydating shows retell the story of Cinderella--but from the prince's perspective.

While some may argue that television's reality-dating version of the Cinderella story creates a heightened context in which the prince has unrealistic power and control, others contend that the role of the prince in an initial dating relationship is not limited to the television world. Many people think they are "ideal partners" in real-life dating situations as well (Wildermuth & Rivera, 2002). Murray, Holmes, and Griffin (1996) found that a significant number of participants in their study described themselves much more positively than they described typical partners. These same participants also tended to describe their own attributes as close to or matching those of ideal partners. According to Wildermuth and Rivera (2002) such "self-defined" ideal partners see themselves as sought-after commodities on the dating market and, thus, see the dating context as their opportunity to choose a partner from an unlimited field of available others who also perceive them to be highly desirable.

Perceptions of what it means to be an ideal partner are subjective in nature, making it difficult to pinpoint shared characteristics that all people who see themselves as ideal

partners believe they possess. However, previous work on self-esteem, social comparison, and narcissism provide a framework for defining the ideal partner construct

(Campbell, Foster, & Finkel, 2002; Franks & Marolla, 1976; Leary & Baumeister, 2000).

Based on previous research, the current study defines ideal partners as people who possess a general positive perception about themselves that includes: (a) high levels of perceived interpersonal self-esteem and (b) high levels of perceived interpersonal power. The idealized self-perceptions of ideal partners are grounded not just in positive views about themselves but, specifically, in positive views about themselves as relational partners (Campbell et al., 2002). Thus, ideal partners' perceptions of high interpersonal self-esteem originate from a sense of strong positive social approval from others (Leary

& Baumeister, 2000), and their perceptions of interpersonal power originate from feelings of effectiveness or power over others (Franks & Marolla, 1976).

Previous communication research has demonstrated that certain relational communicative behaviors are more effective than others at eliciting liking and attraction from potential partners (Bell & Daly, 1984; Myers & Johnson, 2003). For example, communication strategies such as demonstrating physical attractiveness (Hatfield &

Sprecher, 1986), manipulating personal space (Storms & Thomas, 1977), using appropriate nonverbal immediacy behaviors (Hinkle, 1999), and ensuring repeated contact (Saegert, Swap, & Zajonc, 1973) have been found effective at attracting potential partners. However, these traditional relationship initiation strategies may not be the same strategies chosen by ideal partners to attract others. Most date seekers operate under conditions of anxiety, not knowing if dating prospects will accept their requests and fearful of possible embarrassment or rejection (Rowatt, Cunningham, &

Druen, 1999). Such uncertainty dictates cautious and predictable choices of relationship initiation strategies (Ashforth & Fried, 1988). However, ideal partners may see themselves as sought-after and desirable to others and, thus, may be unlikely to feel the same levels of heightened anxiety when approaching potential partners. Ideal partners' low levels of uncertainty may dictate nonnormative choices or uses of traditional relationship initiation strategies.

The majority of previous research on relationship initiation has assessed behaviors without attending to the potential impact individuals' self-perceptions, such as assessing their worth on the dating market, might have on those behaviors (Sprecher & Regan,

2002). The current study addresses the effects of self-perceptions on initiation behaviors. Specifically, social exchange theory provides the framework for examining associations between perceiving oneself as an ideal partner and choosing particular communication strategies to initiate romantic relationships.

Theoretical Framework

Social exchange theory has been used extensively as a framework for examining the communicative behaviors of potential relationship partners during the initial interaction stages of relationships (for summaries, see Hatfield, Traupman, Sprecher, Utne, & Hay,

1985; Sprecher & Schwartz, 1994). Social exchange theory assumes that humans are motivated to obtain rewards and avoid costs (Roloff, 1981). Rewards are anything of value to the person while costs are things that are of negative value to the person

(Sprecher, 1998). When social exchange theory is applied to interpersonal relationships, the relationship initiation behaviors of potential partners often depend on calculations of

the potential rewards and costs of those behaviors (Koper & Jaasma, 2001). When rewards for a particular initiation behavior (i.e., advancing a relationship; selfgratification) are perceived to outweigh the costs necessary to complete the endeavor

(i.e., risk of rejection, time, energy), the behavior is engaged in (Koper & Jaasma, 2001).

According to previous social exchange research, individuals calculate the possible cost/reward outcomes of particular relationship initiation behaviors based partially on comparison levels and comparison level for alternatives (Thibaut & Kelley, 1965).

Comparison levels are internal standards individuals develop that establish the minimum characteristics required of potential partners in the way of rewards and costs.

Comparison levels are determined by individuals' past experiences and exposures to close relationships, as well as other societal influences (Thibaut & Kelley, 1965). As a result, comparison levels vary by individual and are subjective. Based on comparison levels, individuals enter relationships with preexisting expectations about what relationships and relational partners should be like, what features make relationships satisfying and rewarding, and what rules should guide behaviors of relational partners

(Sprecher & Metts, 1999). The internal standards established by ideal partners' comparison levels allow ideal partners to asses what types of relationship initiation behaviors are rewarding (help them meet or exceed their comparison levels) and which behaviors are costly (violate their comparison levels). This in turn, provides an indicator of individuals' relational satisfaction. As long as comparison levels are met or exceeded, individuals will be satisfied.

In addition to comparison levels, people may also use the construct of comparison level for alternatives to determine outcome levels or cost/reward ratios for potential relationship initiation behaviors (Thibaut & Kelley, 1965). The comparison level for alternatives depends on the quality of people's perceived alternative relationship partners. While comparison levels provide a measure of satisfaction, comparison level for alternatives provides a measure of stability. Individuals with high comparison level for alternatives perceive themselves as having the ability to replace existing partners with even more rewarding and attractive potential partners. Individuals with low comparison levels are more likely to perceive themselves as having limited abilities to attract potentially more rewarding partners. Internally assessing the likelihood of finding more suitable partners plays an important role in ideal partners' determinations of cost/reward ratios for engaging in relationship initiation behaviors (Brehm, 1992). For example, if ideal partners believe that they can find a more appealing partner than the one they are presently with, directly asking a prospective partner for a date may be a very low cost behavior. Even if ideal partners are rejected, they can merely move on to someone else or stay in their present relationships. Nonideal partners may be less inclined to pursue alternatives because non-ideal partners may feel they have fewer options if rejected and could possibly jeopardize their existing relationships.

Previous social exchange research suggests that individuals initiating close relationships typically engage in low-cost, low-reward passive relationship initiation strategies (i.e., observation) frequently in the very early stages of a relationship, higher-cost, higherreward active strategies (i.e., asking others for information or rearranging the environment), less frequently, and very high cost, very rewarding interactive strategies

(i.e., interrogating target, self-disclosing to target) least frequently (Berger & Bradac,

1982; Knobloch & Solomon, 2003). However, as stated earlier, these findings may not

be applicable when individuals perceive themselves to be ideal relational partners. Ideal partners' self-perceptions may impact ideal partners' assessments of comparison levels and comparison level for alternatives, which, in turn, may lead ideal partners to calculate the costs and rewards of engaging in particular relationship initiation behaviors differently than nonideals. As a result, ideal partners may engage in different types or different quantities of relationship initiation strategies than those reported in previous relationship initiation research. The following sections discuss how the self-perceptions of esteem and relational power may impact ideal partners' potential comparison levels and comparison level for alternatives and, thus, impact their choice of relationship initiation strategies.

Self-Esteem and Comparison Levels

Individuals possessing high self-esteem often also have very high comparison levels (i.e. high standards for their relational partners) (Levinger & Huesmann, 1980). When individuals have high self-esteem and high standards for others, they may be more likely to select communicative behaviors that are proactive and directly advance relationship initiation. Such strategies would allow them to gather information about potential partners more expediently in order to rapidly ascertain unsuitable partners and/or identify potentially satisfying ones. In contrast to their high comparison levels or standards for their potential partners, people with high self-esteem are likely to have low comparison levels for their own behaviors. Individuals possessing high self-esteem often believe that others positively value them. As a result, they can "get away" with treating people in unorthodox ways without negative results (Murray, Holmes, & Griffin, 2000). For example, researchers have found that high self-esteem individuals feel confident engaging in more nontraditional communicative behaviors in relationships because it is easy for them to generate reasons why their partners should like them anyway (Murray et al., 2000). Essentially, individuals with high self-esteem believe that their partners are more lenient with them, because their partners see as many virtues in them as they see in themselves (Murray et al., 2000).

A variety of research exists to support this idea that people with high self-esteem may be more likely to engage in relationship initiation behaviors in ways that violate the traditional slow and cautious use of such behaviors found in previous social exchange research. For example, while Ting-Toomey (1984) found that high levels of selfdisclosure and expressions of liking early on in courtship situations were considered very costly because these behaviors increase vulnerability, Murray et al. (2000) found that high self-esteem individuals engaged in greater levels of such self-disclosures during early courtship. Additional research has also shown that people with high self-esteem engaged in more potentially costly conversation initiation behaviors than people who were shy (Manning & Ray, 1993). High self-esteem individuals were more likely than shy people to: initiate conversations, talk about personal topics rather than topics related to the setting, and ask probing questions (Manning & Ray, 1993). Finally, Vangelisti,

Knapp, and Daly (1990) and Campbell, Foster, and Finkel (2002) found that individuals who highly valued themselves were more likely to engage in potentially high cost conversational behaviors such as boasting and bragging about the self, using humor, showing off, making others approach them, engaging in high levels of self-disclosure, manipulating events/environments, expressing superiority, and deception.

Thus, evidence exists to support the idea that perceptions of high self-esteem impact people's choices of relationship initiation behaviors. Ideal partners have high levels of perceived interpersonal self-esteem based on positive social approval from others

(Leary & Baumeister, 2000). Therefore, research on the relationship initiation strategies of people who perceive themselves as ideal may result in similar findings to the research on people with high self-esteem. Ideal partners may also be more open to applying proactive initiation strategies.

Power and Comparison Level for Alternatives

Perceptions of power may interact with comparison level for alternatives such that when individuals perceive that they have multiple attractive and available alternatives, they feel more powerful. Perceptions of power are also enhanced when relational partners believe that their partners have limited alternatives to the present relationship (Murray et al.,

2005; Safilios-Rothschild, 1967). "In a relationship between just two people, power and dependency are inversely related: the less dependency, the more power. If you are less dependent on the relationship than is your partner, then you have more power over the partner than he or she has over you" (Brehm, 1992, p. 232).

In situations where individuals perceive greater power over their relational partners, individuals with the greater power obtain better reward-cost positions within the relationship (Thibaut & Kelley, 1965). This high power status may allow rewards to stay high while lowering the costs of engaging in traditionally high-risk communication strategies to initiate relationships. Thus, individuals with perceptions of higher power status may also engage in relationship initiation behaviors that violate slow and cautious use of such behaviors early in relationships. Numerous studies have found that individuals with high-perceived power are willing to engage in relationship initiation behaviors that traditionally would be considered more costly in order to reap the high rewards that may come if such strategies are successful. For example, Duran (1992) and Vangelisti et al. (1990) found that people with higher power engaged in conversational strategies such as expressing humor, engaging in risky non-verbals, engaging in self-disclosure, expressing controversial ideas, expressing conversational narcissism, and engaging in self-focused conversation early on in close relationships.

Ting-Toomey (1984) noted that people with higher power in relationships engaged in more communicative behaviors that orchestrate the development of relationships, including making decisions and taking control of situations. Finally, Campbell et al.

(2002) found that people with perceived power engaged in relationship initiation behaviors that allowed them to maintain that sense of power. These behaviors included game-playing, maintaining or initiating multiple relationships at one time, promoting self, and engaging in sexual relations.

Research findings suggest that perceptions of high power impact people's choices of relationship initiation behaviors. Ideal partners may perceive a sense of power or control over their relational partners. On the other hand, ideal partners may not feel that they are dependent upon their relational partners for rewarding relationships, but instead they view themselves as having other positive alternatives. Thus, ideal partners may not perceive their partners as having high amounts of power over them. As a result, ideal partners may also be more open to applying proactive initiation strategies.

Based on high self-esteem and related comparison levels, and high perceptions of power and related comparison level for alternatives, ideal partners may perceive the rewards of dating relationships to be high and the costs of engaging in communication strategies to initiate these relationships to be low. As a result, ideal relational partners may be more willing to engage in relationship initiation strategies that others have traditionally refrained from during the very early stages of a potential relationship (Berger

& Bradac, 1982). Previous research has examined the characteristics others look for when searching for ideal partners (Murray et al., 1996). However, little is known about self-proclaimed ideal partners and their relational behaviors. In response, the current exploratory study is interested in examining the communication strategies employed by ideal partners when initiating dating relationships. Following the model of Vangelisti et al.

(1990) the behavioral outcomes of self-perceptions are examined. What do people do and say in initial interactions when they perceive themselves to be ideal partners? Based on the previous research findings shared, the following exploratory research question was advanced:

RQI: What are the relationship initiation communication strategies used by individuals who perceive themselves to be ideal partners?

Method

Participants

Two hundred forty-four individuals enrolled at a midsized Midwestern university participated in this study. All participants were enrolled in undergraduate communication classes. Ninety-four participants were male and 145 were female (five individuals did not identify their biological sex). Participants ranged in age from 17-34, with an average age of 20.28 (SD = 1.96). Participants were reasonably distributed across class rankings, with 33% sophomores, 26% seniors, and 21% and 20% juniors and freshmen, respectively. The vast majority of participants were Caucasian (93%), followed by

African American (3%) and other ethnic groups (4%).

Procedure

Participants were given an overview of the study by one of the researchers before receiving a questionnaire that included several demographic items. In order to identify the verbal and nonverbal dating initiation behaviors enacted by people who perceive themselves to be ideal partners, participants were asked to reflect on and to share strategies that might be done or said by themselves in an initial dating situation if they felt they were in the position of being an ideal relational partner. Specifically, participants were given the following instructions:

The goal of the current study is to generate a list of different

behaviors that people who are operating in an "I am the ideal

relational partner" mind-set might use when searching for a

potential mate. Someone with the "ideal" mind-set has high

self-esteem and perceives him/herself to be a "great catch" on

the dating market. These people see themselves as sought-after

commodities on the dating scene with the power to choose a

partner from a large field of available and willing others.

Imagine that you are someone with this "I am the ideal" mind-set

who is looking for a potential romantic relationship partner. In

essence, you are seeking a relationship in which your potential

partner sees you as highly rewarding to be with, and the best

possible relational partner that he/she could have out of all

other available partners. Please generate examples of verbal and

nonverbal communication strategies that you might use to initiate

a potential dating relationship if you were in such a situation.

Please be as descriptive and detailed as possible in your ideas.

Thank you.

Participants were given as much time as they needed to complete the questionnaire and were encouraged to generate as many strategies as possible. Extra credit was given upon completion of the questionnaire and the participants were thanked for their participation.

Content Analysis Procedures

There were a total of 1183 communication strategies identified by participants. A content analysis was performed to analyze these strategies. Each strategy was written on a separate index card, and then three coders independently reviewed a different selection of index cards in order to become familiar with the strategies. Once each coder was acquainted with a portion of the reported strategies, the coders generated a preliminary list of categories to encompass the content of the strategies generated. Strategies identified within the bodies of research on relationship initiation and mate selection provided the initial categorical structure for this study. Each category was reviewed and conceptualized so that (a) shared understanding was attained across coders for each category and (b) categories remained mutually exclusive.

The coders then established intercoder reliability of the categorical structure. After a preliminary reliability check on 25 of the strategies across the three coders, modifications were made to the categorical structure to either create additional categories as needed or to provide further clarification and separation between categories. Then a second reliability check was made between coders using 25 different strategies and the revised categorical structure. The second reliability check indicated an intercoder reliability alpha coefficient of .84. This coefficient is within acceptable parameters for performing a content analysis (Krippendorff, 1980).

Results

The 1183 communication strategies were coded into one of fifteen possible categories.

Each category is explained briefly in the order of frequency and total sample percentage.

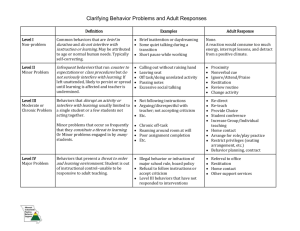

Sample strategies for each category are also provided. See Table 1 for a summary of the frequencies and percentages of each strategy.

Initiation Strategies (147, 12.4%)

This strategy involves taking charge and initiating relational events. Examples of this strategy include "I would ask him if he wanted to go see a movie with me," "I would directly go up and ask them out," and "I would initiate getting her phone number."

Emotional Disclosures (138, 11.7%)

This strategy requires directly expressing feelings for or about potential partners.

Examples of this strategy include "You are special," "I care about you," "I want a relationship with you," and "I think we are perfect for one another."

Direct Inquiry to Relational Partner (135, 11.4%)

This strategy refers to directly seeking out potential relational partners to talk about likes, dislikes, or relational issues. Examples of this strategy include "I would flat out ask the person what they look for in a relationship," "Ask about past relationships, who was in control and how she felt about it," and "Ask her directly where she stands on premarital sex, religion, and kids."

Impression Management (131, 11.1%)

This strategy focuses on managing physical appearance or actions in order to present a favorable image to others. Examples of this strategy include "I would make sure all of my good qualities are evident (personality, smile, etc.)," "I would try to be smarter so they would look at me as being the best," "I would dress nice, sexy when around them so they'd notice that I am perfect," or "I'd keep myself looking good, stay fit, work out."

Shared Activities (111, 9.4%)

This strategy involves doing things together with a potential relational partner, but with the primary decision making about "what to do" being made by the ideal partner.

Examples of this strategy include "I would include her in things that I like to do," "I love basketball so I would ask him if he wanted to go to a Bucks game," and "I would spend as much time with her as I could doing stuff with her that I like to make sure that she is exactly what I want."

Supportive Behaviors (106, 9.0%)

This strategy focuses on doing things to help out potential relational partners with the intent to please. Examples of this strategy include "I'd help them with their homework if they were bad in a particular subject," "I'd communicate well, listen to what he is saying, be responsive and intelligent," "I would do everything I feel that I want to do for them," or

"I would make sure to please him/her in any way that I felt necessary."

Indirect Information-Gathering (94, 7.9%)

This strategy entails using others to gather, to discuss, or to share information about potential relational partners. Examples of this strategy include "I would talk to her friends to find out her likes and dislikes," "I would gather as much information about him as I could from his friends before approaching him."

Gift Giving (76, 6.4%)

This strategy requires the giving of physical or tangible rewards to potential relational partners. Examples of this strategy include "I would definitely take her to dinner and a movie. Although it's kind of cheesy nowadays, it's a nice thing to do," "I would take them to special places on dates. For example, a nice place for dinner, and a walk by the lake at night in the springtime," "I would buy her flowers," or "Buy gifts to show you care."

Compliments (59, 5.0%)

This strategy involves giving praise or public acknowledge to potential relational partners. Examples of this strategy include "I'd say something everyday about how good she looks even though she might not be that good looking. Odds are, she's never been told that," "Compliment his looks, his clothes, his smile," "I'd tell her that making her happy makes me happy," or "Tell him that he is one of the few really nice men I've ever met."

Other-Initiated Strategies (44, 3.7%)

This strategy refers to when ideal partners wait for others to initiate a relationship with them. The ideal partner does not need to exert much energy or effort; they simply wait until someone first approaches them. Examples of this strategy include "Let them call you," "I would not look for someone. I would wait for the right person to come to me,"

"Appearing uninterested--play hard to get, sit back and let them try to get me" or "I would show them just enough attention so they know I'm alive."

Assistance from Others: Impression Management (42, 3.5%)

This strategy requires using others to assist in impression management of ideal partners, through the manipulation of events or other individuals. Examples of this strategy include "Suck up to the parents. That always helps," "Build yourself up to their friends," "Introduce her to my nieces and nephews to show her how good I am with kids.

Girls go for that," "Being a woman I would take him out somewhere where I know other men would hit on me to show him I am very desirable," and "Show them you have many friends and you are popular."

Self-Acceptance (41, 3.5%)

This strategy refers to when ideal partners demonstrate a comfortable acceptance of themselves, and feel that there is no need to change anything about themselves for their potential relational partners. Examples of this strategy include "Talk to them and be myself because I am, in fact, perfect," "I would act like I normally do," "I would be myself around them" or "I would not change my actions or behaviors around this person."

Pickup Lines (29, 2.5%)

This strategy includes brief, memorable phrases or statements used by ideal partners that are designed to have immediate results on potential partners. Examples of this strategy include "If I could rearrange the alphabet I would put U and I together," "Baby, your daddy must be a garbage man--'cuz you got the junk," or "Is that a mirror in your pocket, 'cause I can see myself in your pants."

Bragging (18, 1.5%)

This strategy focuses on enhanced or embellished statements made by ideal partners that are self-promoting in nature. Examples of this strategy include "Brag about myself.

Make small achievements seem important," "I would boast about accomplishments," "I would say that he can't get any better than me" or "Tell him that I just got an excellent job offer."

Humor (12, 1.0%)

This strategy refers to statements or references made by ideal partners that are designed to get potential relational partners to laugh or to display the ideal partner's sense of humor. Examples of this strategy include "I would joke with them," "I would

tease them," "I would make sarcastic comments so he would laugh," "Crack jokes--not about her of course," or "I would try to be funny."

Supplemental Analysis

While both male and female participants discussed all 15 categories, the frequencies reported for the categories differed by respondent sex (see Table 2 and Table 3). Five differences in the order of frequency used were notable. First, the most frequently reported category for males was initiation strategies and the third most frequently reported strategy was emotional disclosures. However, for the females, the frequency for those two strategies was exactly the opposite. The category of emotional disclosures was the most frequently reported category for females while initiation strategies was third. Additionally, the strategy of other-initiation was the 8th most frequently reported for males, but only the 13th most frequently reported for females. The strategy of compliments was only the 12th most frequently cited for males, but was the 9th most frequently mentioned for females. Thus, it appears that the strategies most frequently identified by ideal partners to attract potential relational partners may vary based on the sex of the ideal partner.

Discussion

This study examined possible communication strategies utilized by ideal partners to initiate relationships. The following paragraphs summarize the findings from the current study and discuss how these findings both support and extend previous research on social exchange, self-esteem and comparison levels, and power and comparison level for alternatives.

Support for Previous Research

Previous social exchange research reported that individuals with high self-esteem and high power were more likely to engage in potentially high-cost communication strategies such as initiating conversations (Manning & Ray, 1993), self-disclosure (Murray et al.,

2000), asking questions (Manning & Ray, 1993), and manipulating events/environments

(Campbell et al., 2002; Vangelisti et al., 1990). The results from the current study parallel these findings. In the current study, the most frequently reported relationship initiation behaviors by ideal partners were initiating talk, emotional self-disclosures, direct inquiry, and impression management (manipulating self or environment to make an impression).

Combined, these four strategies accounted for 46.5% of the 1183 strategies generated.

These findings suggest that when individuals perceive themselves to be ideal partners, the levels of self-esteem and power associated with this classification may impact ideal partners' perceptions of comparison levels and comparison level for alternatives such that the costs of engaging in certain relationship initiation strategies are decreased. For example, expressing personal feelings and emotions is traditionally seen as a costly relationship initiation strategy because this strategy could involve rejection or loss of respect (Adler, Rosenfeld, & Towne, 1992). However, if successful, such personal selfdisclosures can be highly rewarding as they are also related to increased liking and attraction (Adler et al., 1992). Thus, ideal partners' willingness to engage in emotional self-disclosures in the initial stages of relationships suggests that ideal partners may

perceive the potential costs of such strategies to be mitigated, while the potential rewards are unchanged.

Extensions to Previous Research

The current study provides several opportunities to extend past research findings. First, previous social exchange research found that individuals with high self-esteem and high power were more likely to engage in high-cost communication strategies such as bragging, using humor, and making the other approach him/her (Campbell et al., 2002;

Vangelisti et al., 1990). In the current study, participants also reported the relationship initiation strategies of bragging, using humor, and making the other approach (otherinitiation). However, these strategies were reported with only moderate to low frequency.

The three strategies of bragging, humor, and other-initiation combined only accounted for 6.2% of the total number of strategies reported.

These findings may indicate that the associations inferred between high self-esteem, power, and perceptions of ideal partner status may only reduce the usage of traditionally high-cost relationship initiation behaviors to a limited extent. Using strategies such as bragging, humor, and waiting for the other partner to initiate interaction may still be perceived as highly costly, even for ideal partners. For example, de Koning and Weiss

(2002) found that an inappropriate or unappreciated use of humor in relationships has very negative consequences on the quality of relationships. Thus, a poorly timed joke or an overly suggestive pickup line may be harmful, even to individuals with ideal partner status. The rewards of such behaviors may not outweigh the potential costs. As a result, ideal partners may engage in these strategies less frequently.

Second, previous scholarship on social exchange and relational development indicated that individuals were cognizant of the costs and rewards involved in relationship initiation behaviors and tended to move cautiously through relationship stages, being certain to enact stage-appropriate behaviors along the way to reduce potential costs (Berger &

Bradac, 1982; Knobloch & Solomon, 2003). However, results from the current study did not concur with these findings. For example, although previous research indicated that observing potential partners was a frequent first step when trying to initiate relationships

(Berger & Bradac, 1982), participants in the current study did not list passive observation as a dating initiation strategy used by ideal partners. Additionally, while previous work stated that more active, potentially costly strategies such as gathering information from others, interrogating potential partners, or self-disclosing to potential partners were not commonly used strategies in the very early stages of relationships (Berger & Bradac,

1982; Knobloch & Solomon, 2003), the current study found that asking potential partners direct questions about themselves and engaging in emotional self-disclosures were two of the most frequently reported strategies. Additionally, gathering information indirectly from others was a strategy reported with moderate frequency.

Thus, participants in this study may not practice the traditional "low cost strategies first" model found in previous research. Differences in self-perceptions appear to be reflected in differences in the strategic decisions and tactical moves that individuals employ when initiating relationships. When people hold self-perceptions encompassing high selfesteem and power (as ideal partners do), their choices of relational initiation strategies appear to undergo a transformation such that they are more willing to engage in

proactive strategies. This finding suggests that there is significant value in examining the role played by self-perception in the formation of close relationships (Sprecher & Regan,

2002), as self-perceptions of ideal partner status appear to influence the relationship initiation behaviors ideal partners employ.

Finally, earlier research on self-esteem and power typically identified self-focused relationship initiation behaviors (i.e., bragging, self-disclosure, initiating conversation, manipulation) (Campbell et al., 2002). However, participants in the current study also consistently reported other-focused behaviors. For example, participants identified otherfocused strategies such as supportive behaviors, shared activities, gift giving, and compliments, as relationship initiation strategies ideal partners would use with moderate frequency. The willingness to use other-focused strategies suggests that ideal partners may not be purely focused on their own costs and rewards in the relationships. Ideals may also be cognizant of the need to provide rewards and to reduce costs for the other person in the relationship as well. As a result, ideal partners may be vulnerable, since these strategies suggest that ideal partners may be willing to invest themselves in the relationships' success. These strategies (i.e., supportive behaviors, shared activities, gift giving, and compliments) share a number of similarities with typologies of affinityseeking and relationship maintenance (Bell & Daly, 1984; Stafford & Canary, 1991).

Thus, the potential use of these strategies may indicate that ideal partners may desire to see relationships progress beyond initiation.

Limitations

Several issues should be taken into account when interpreting the findings of this study.

First, this study asked individuals to self-report strategies they would use if they were ideal relational partners. There was no induction check to verify if people actually could imagine themselves as ideals. Since the data is limited to imagined perceptions, the behaviors reported could be based on stereotypes of ideals rather than accurate reflections of what self-defined ideals would do. Future research should confirm whether or not these strategies are actually utilized by individuals who consciously consider themselves to be ideal relational partners.

Second, participants were not provided with an explicit definition of the exact characteristics (i.e., good looking, intelligent) of ideal partners. Individuals were given latitude to determine the nuances of ideal partners for themselves. This latitude was determined appropriate because this study was not interested in the exact characteristics of ideal mates. Rather, this study was interested in self-perceptions associated with being ideal. Following the model of Murray et al. (1996), participants were asked to envision a general construct and then allowed to infer their own unique standards to that construct in the hopes of obtaining actual idiosyncratic visions rather than just a generic cultural standard. While self-constructions were appropriate in this study, future research may wish to clarity the construct of ideal partner further for participants.

Several other limitations are worth noting. First, individuals were not asked to indicate whether they were envisioning themselves to be ideal partners for someone in a samesex or an opposite-sex relationship. As a result, there may be an inherent bias toward ideal relational partners in heterosexual relationships. Second, the sample utilized was

very homogeneous. Future studies should solicit input from other cultures to assess what level of variance, if any, exists in the strategies selected by ideal partners from non-

Caucasian groups. Finally, some might have concerns because the participants were undergraduate students. While it would be interesting to compare and to assess the communication strategies of ideal partners in different age groups, this should not belittle the strategies generated by college students. Dating and relationship development are very important topics to undergraduates. Thus, college students' perceptions are appropriate for this line of research.

Directions for Future Research

There are several logical extensions to this study. For example, how successful or effective are ideal partner communication strategies over the long-term? Research by

Paulhus (1998) found that self-enhancing illusions might be beneficial in the short term but maladaptive over the long term. Does this hold true for ideal partners' selfperceptions as well? Additionally, previous communication research has demonstrated that some relational communicative behaviors are more effective than others at eliciting liking and attraction from potential partners (Bell & Daly, 1984; Myers & Johnson, 2003).

Are the strategies that ideal partners report using with the most frequency actually the strategies that are most effective at initiating close relationships? Past research indicates that those who see themselves positively are more likely to engage in behaviors that promote success (Taylor & Brown, 1988). Additionally, the self-fulfilling prophecy construct would predict that the more we believe ourselves to be great partners, the more we try to engage in behaviors to protect that belief, so the more we actually become better/more ideal partners (Jones, 1977). Such research indicates that ideal partners may, in fact, be engaging in strategies geared for success and research examining this question may be illuminating.

Additionally, although this study did not focus on sex differences in ideal partners' strategy usage, the supplemental analysis performed suggests that males and females may utilize different strategies as ideal partners. Television programs, such as The

Bachelor and The Bachelorette, also provide anecdotal evidence that ideal partners may vary their strategy usage based on ideal partner sex. As a result, the biological sex of the ideal partner may be a variable worthy of future examination.

A final interesting line of related research might answer the question, "What do ideal partners look for in a partner?" Sedikides, Rudich, and Gregg (2004) reported that individuals with positive self-illusions are often attracted to partners with lower selfesteem who express admiration and gratitude to them. However, Murray et al. (1996) and Murray, Holmes, Bellavia, and Griffin (2002) found that individuals with highly positive self-perceptions look for partners who are reflections of themselves and, thus, also have high self-esteem and confidence. Additional scholarship examining the types of people ideal partners are attracted to may illuminate inconsistencies such as this one.

In sum, while the current study provides a starting point for exploring the role that selfperceptions of ideal partner status have on relationship initiation behaviors, additional research is still needed. As popular culture continues to play a role in framing individuals' perceptions of what relationships should or could be like, more people may strive to become the ideal partners that others seek or pursue. As long as television

programming and motion pictures continue to show viewers the benefits of being ideal partners, people will continue to dream about what it might be like to be in that position.

Indeed, many may already consider it to be a part of their reality--as one student casually shared after the data collection was complete, "I am a Super Man, and everyone wants to be with me!" Thus, understanding the implications of this mind-set on the formation of close relationships may be even more important in the future.

References

Adler, R. B., Rosenfeld, L. B., & Towne, N. (1992). Interplay: The process of interpersonal Communication (5th ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Ashforth, B. E. & Fried, Y. (1988). The mindlessness of organizational behaviors. Human

Relations, 41, 305-329.

Bell, R. A. & Daly, J. A. (1984). The affinity-seeking function in communication.

Communication Monographs, 51, 91-115.

Berger, C. R. & Bradac, J. J. (1982). Language and social psychology: Uncertainty in interpersonal relations. London: Arnold.

Brehm, S. S. (1992). Intimate relationships. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Campbell, W. K., Foster, C. A., & Finkel, E. J. (2002). Does self-love lead to love for others? A story of narcissistic game playing. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 83, 340-354. de Koning, E. & Weiss, R. L. (2002). The relational humor inventory: Functions of humor in close relationships. American Journal of Family Therapy, 30, 1-18.

Duran, R. L. (1992). Communication adaptability: A review of conceptualization and measurement. Communication Quarterly, 40, 253-268.

Franks, D. D. & Marolla, J. (1976). Efficacious action and social approval as interacting dimensions of self-esteem: A tentative formulation through construct validation.

Sociometry, 39, 324-341.

Hatfield, E. & Sprecher, S. (1986). Mirror, mirror ... The importance of looks in everyday life. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Hatfield, E., Traupman, J., Sprecher, S., Utne, M., & Hay, J. (1985). Equity and intimate relations: Recent research. In W. Ickes (Ed.), Compatible and incompatible relationships

(pp. 91-117). New York: Springer.

Hinkle, L. L. (1999). Nonverbal immediacy communication behaviors and liking in marital relationships. Communication Research Reports, 16, 81-90.

Jones, R. A. (1977). Self-fulfilling prophecies: Social, psychological, and physiological effects of expectancies. Oxford: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Knobloch, L. K. & Solomon, D. H. (2003). Responses to changes in relational uncertainty within dating relationships: Emotions and communication strategies. Communication

Studies, 54, 282-305.

Koper R. J. & Jaasma, M. A. (2001). Interpersonal style: Are human social orientations guided by generalized interpersonal needs? Communication Reports, 14, 117-129.

Krippendorff, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Newbury

Park, CA: Sage.

Leary, M. R. & Baumeister, R. F. (2000). The nature and function of self-esteem:

Sociometer theory. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology,

32, (pp. 2-51). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Levinger, G. & Huesmann, L. R. (1980). An "incremental exchange" perspective on the pair relationship: Interpersonal reward and level of involvement. In K. K. Gergen, M. S.

Greenberg, & R. H. Willis (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp.

165-188). New York: Plenum.

Manning, P. & Ray, G. (1993). Shyness, self-confidence, and social interaction. Social

Psychology Quarterly, 56, 178-192.

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., Bellavia, G., & Griffin, D. W. (2002). Kindred spirits? The benefits of egocentrism in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 82, 563-581.

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. W. (1996). The benefits of positive illusions:

Idealization and the construction of satisfaction in close relationships. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 79-98.

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Griffin, D. W. (2000). Self-esteem and the quest for felt security: How perceived regard regulates attachment processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 478-498.

Murray, S. L., Rose, P., Holmes, J. G., Derrick, J., Podchaski, E. J., Bellavia, G., &

Griffin, D. W. (2005). Putting the partner within reach: A dyadic perspective on felt security in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 327-

347.

Myers, S. A. & Johnson, A. D. (2003). Verbal aggression and liking in interpersonal relationships. Communication Research Reports, 20, 90-96.

Paulhus, D. L. (1998). Interpersonal and intrapsychic adaptiveness of trait selfenhancement: A mixed blessing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74,

1197-1208.

Roloff, M. E. (1981). Interpersonal communication: The social exchange approach. New

York: Sage.

Rowatt, W. C., Cunningham, M. R., & Druen, P. B. (1999). Lying to get a date: The effect of facial physical attractiveness on the willingness to deceive prospective dating partners. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16, 209-223.

Saegert, S. C., Swap, W., & Zajonc, R. (1973). Exposure, context, and interpersonal attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 25, 234-242.

Safilios-Rothschild, C. (1967). A macro- and micro-examination of family power and love: An exchange model. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38, 355-362.

Sedikides, C., Rudich, E. A., & Gregg, A. P. (2004). Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy?: Self-esteem matters. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 87, 400-416.

Sprecher, S. (1998). Social exchange theories and sexuality. Journal of Sex Research,

35, 32-43.

Sprecher, S. & Metts, S. (1999). Romantic beliefs: Their influence on relationships and patterns of change over time. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16, 834-851.

Sprecher, S. & Regan, P. C. (2002). Liking some things (in some people) more than others: Partner preferences in romantic relationships and friendships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19, 463-481.

Sprecher, S. & Schwartz, P. (1994). Equity and balance in the exchange of contributions in close relationships. In M. J. Lerner & G. Mikula (Eds.), Entitlement and the affectional bond (pp. 11-41). New York: Plenum.

Stafford, L. & Canary, D. J. (1991). Maintenance strategies and romantic relationship type, gender, and relational characteristics. Journal of Personal Relationships, 8, 217-

242.

Storms, M. & Thomas, G. (1977). Reactions to physical closeness. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 35, 412-418.

Taylor, S. E. & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 193-210.

Thibaut, J. W. & Kelley, H. H. (1965). The social psychology of groups. New York: Wiley.

Ting-Toomey, S. (1984). Communication of love and decision-making power in dating relationships. Communication, 13, 17-29.

Vangelisti, A. L., Knapp, M. L., & Daly, J. A. (1990). Conversational narcissism.

Communication Monographs, 57, 251-274.

Wildermuth, S. M. & Rivera, J. (2002). Social exchange in close relationships: Is it best to have the ideal partner or to be the ideal partner? Paper presented at the Central

States Communication Association's 2002 Convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Susan M. Wildermuth (Ph.D. 2001, University of Minnesota) is an Assistant Professor,

Sally Vogl-Bauer (Ph.D. 1994, University of Kentucky) is an Associate Professor, and

Julimar Rivera (Master's Candidate 2004, University of Wisconsin--Whitewater) is a graduate student in the Department of Communication at the University of Wisconsin--

Whitewater. A version of this paper was presented at the 2004 Central States

Communication Association Convention held in Cleveland, Ohio. Correspondence to:

Susan M. Wildermuth, Department of Communication, University of Wisconsin-

Whitewater, Whitewater, WI 53190. Tel.: (262) 472-5064; E-mail: wilderms@uww.edu

Table 1 Overall Frequencies of Ideal Partner

Communicative Strategies

Times

Ranking Communicative strategy reported

1 Initiation Strategies 147 (12.4%)

2 Emotional Disclosures 138 (11.7%)

3 Direct Inquiry to Relational Partner 135 (11.4%)

4 Impression Management 131 (11.1%)

5 Shared Activities 111 (9.4%)

6 Supportive Behaviors 106 (9.0%)

7 Indirect Information-Gathering 94 (7.9%)

8 Gift Giving 76 (6.4%)

9 Compliments 59 (5.0%)

10 Other-Initiated Strategies 44 (3.7%)

11 Assistance from Others: 42 (3.5%)

Impression Management

12 Self-Acceptance 41 (3.5%)

13 Pickup Lines 29 (2.5%)

14 Bragging 18 (1.5%)

15 Humor 12 (1.0%) n = 1183.

Table 2 Overall Frequencies of Ideal Partner

Communicative Strategies--Males Only

Times

Ranking Communicative strategy reported

1 Initiation Strategies 71 (15.3%)

2 Impression Management 55 (11.8%)

3 Direct Inquiry to 47 (10.1%)

Relational Partner

4 Emotional Disclosures 45 (9.7%)

5 Supportive Behaviors 44 (9.5%)

6 Shared Activities 40 (8.6%)

7 Indirect Information-Gathering 37 (8.0%)

8 Other-Initiated Strategies 27 (5.8%)

9 Gift Giving 23 (4.9%)

10 Self-Acceptance 19 (4.1%)

11 Assistance from Others: 18 (3.9%)

Impression Management

12 Compliments 16 (3.4%)

13 Humor 9 (1.9%)

14 Bragging 8 (1.7%)

15 Pickup Lines 6 (1.3%) n = 465.

Table 3 Overall Frequencies of Ideal Partner

Communicative Strategies--Females Only

Times

Ranking Communicative strategy reported

1 Emotional Disclosures 93 (13.0%)

2 Direct Inquiry to 88 (12.3%)

Relational Partner

3 Impression Management 76 (10.6%)

3 Initiation Strategies 76 (10.6%)

5 Shared Activities 71 (9.9%)

6 Supportive Behaviors 62 (8.6%)

7 Indirect Information-Gathering 57 (7.9%)

8 Gift Giving 53 (7.4%)

9 Compliments 43 (6.0%)

10 Assistance from Others: 24 (3.3%)

Impression Management

11 Pickup Lines 23 (3.2%)

12 Self-Acceptance 22 (3.1%)

13 Other-Initiated Strategies 17 (2.4%)

14 Bragging 10 (1.4%)

15 Humor 3 (.4%) n = 718.