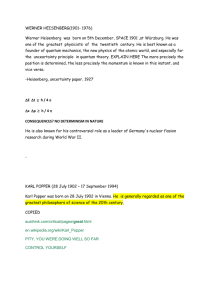

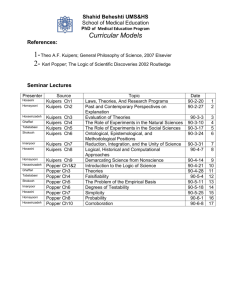

Karl Raimund Popper - PhilSci

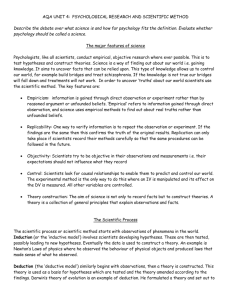

advertisement