HNELHD_CG_12_TBA_Meningococcal_Management_2_

advertisement

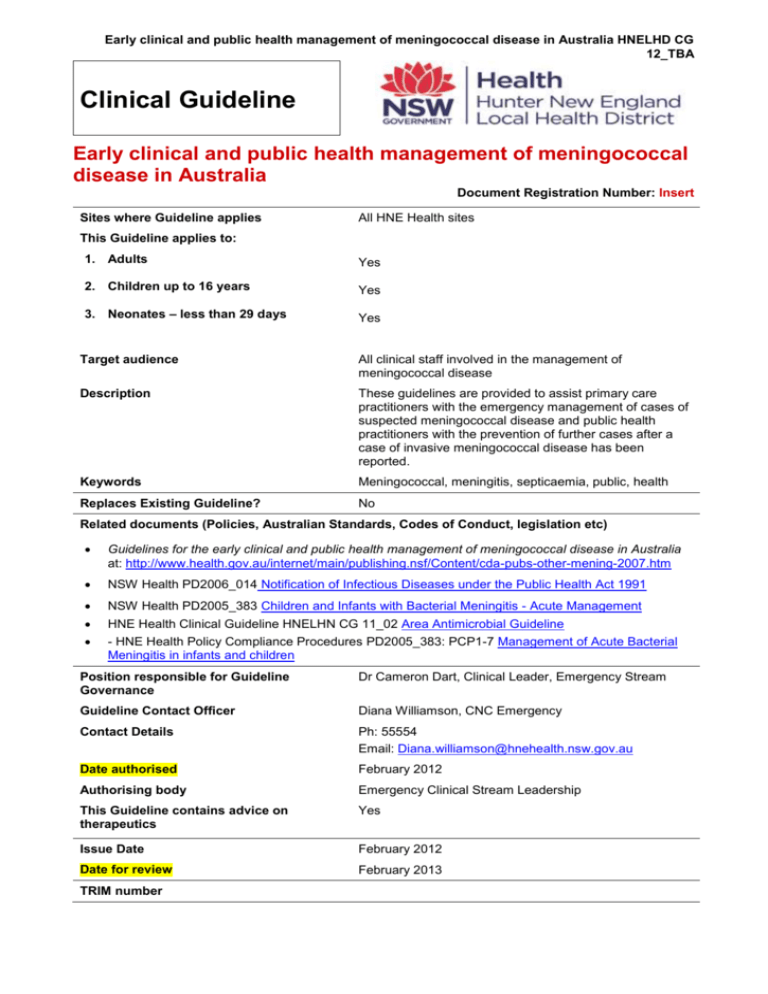

Early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia HNELHD CG 12_TBA Clinical Guideline Early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia Document Registration Number: Insert Sites where Guideline applies All HNE Health sites This Guideline applies to: 1. Adults Yes 2. Children up to 16 years Yes 3. Neonates – less than 29 days Yes Target audience All clinical staff involved in the management of meningococcal disease Description These guidelines are provided to assist primary care practitioners with the emergency management of cases of suspected meningococcal disease and public health practitioners with the prevention of further cases after a case of invasive meningococcal disease has been reported. Keywords Meningococcal, meningitis, septicaemia, public, health Replaces Existing Guideline? No Related documents (Policies, Australian Standards, Codes of Conduct, legislation etc) Guidelines for the early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-pubs-other-mening-2007.htm NSW Health PD2006_014 Notification of Infectious Diseases under the Public Health Act 1991 NSW Health PD2005_383 Children and Infants with Bacterial Meningitis - Acute Management HNE Health Clinical Guideline HNELHN CG 11_02 Area Antimicrobial Guideline - HNE Health Policy Compliance Procedures PD2005_383: PCP1-7 Management of Acute Bacterial Meningitis in infants and children Position responsible for Guideline Governance Dr Cameron Dart, Clinical Leader, Emergency Stream Guideline Contact Officer Diana Williamson, CNC Emergency Contact Details Ph: 55554 Email: Diana.williamson@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au Date authorised February 2012 Authorising body Emergency Clinical Stream Leadership This Guideline contains advice on therapeutics Yes Issue Date February 2012 Date for review February 2013 TRIM number Early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia HNELHD CG 12_TBA Note: Over time links in this document may cease working. Where this occurs please source the document in the PPG Directory at: http://ppg.hne.health.nsw.gov.au/ GUIDELINE SUMMARY This document establishes best practice for HNE Health. While not requiring mandatory compliance, staff must have sound reasons for not implementing standards or practices set out within the guideline, or for measuring consistent variance in practice. Introduction This document provides clinicians with a useful integrated document to help guide and inform their practice, and enhances the early and consistent approach to the management of meningococcal disease. This guideline has been developed by the District Meningococcal Review Committee and approved for use by the Emergency Clinical Stream. Situation The Communicable Disease Network Australia (CDNA) and Australian Government of Health and Aging have developed clinical guidelines for the early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia. Topics covered in the Guidelines include: Emergency management of suspected invasive meningococcal disease in general practice ;( Chapter 2) Early (emergency department) hospital management of suspected invasive meningococcal disease; (Chapter 3) Laboratory tests and their use; (Chapter 4) Public health management of sporadic cases of invasive meningococcal disease; (Chapter 8) Public health management of outbreaks of cases of invasive meningococcal disease; Chapter 9) Reporting and public health surveillance of meningococcal disease. (Chapter 6) Background This guideline seeks to ensure a standard approach to monitoring, notifying and managing Meningococcal disease supported by the District Meningococcal Review Committee as acceptable practice. Assessment Clinicians treating patients with suspected meningococcal disease also consider the application of the following documents: NSW Health PD2006_014 Notification of Infectious Diseases under the Public Health Act 1991 NSW Health PD2005_383 Children and Infants with Bacterial Meningitis – Acute Management HNE Health PD2005_383 PCPs from one to seven Management of Acute Bacterial Meningitis in Infants and Children HNE Health CG 11_02 Area Antimicrobial Guideline Recommendation Along with the above documents, clinicians also refer to the Guidelines for the early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia from the CDNA. Version One February 2012 Page 2 Early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia HNELHD CG 12_TBA GUIDELINE This document reflects what is currently regarded as safe and appropriate practice. Staff must be aware, however, that in any clinical situation there may be many factors that cannot be covered by a single document and therefore does not replace the need for the application of clinical judgment in respect to each individual patient. All clinical staff in HNE Health are to be familiar with the Guidelines for the early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia at: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-pubs-other-mening-2007.htm The following documents also apply: 1. For children refer to HNE Health Policy Compliance Procedures PD2005_383: PCP 1 to 7 Management of Acute Bacterial Meningitis in infants and children 2. Notifiable diseases must be reported as described in PD2006_014 Notification of Infectious Diseases under the Public Health Act 1991 3. NSW Health PD2005_383 Children and Infants with Bacterial Meningitis – Acute Management 4. HNE Health CG 11_02 Area Antimicrobial Guideline Key points for pre-hospital care Meningococcal septicaemia has considerably greater mortality than meningococcal meningitis and is often characterised by a rapidly evolving petechial or purpuric rash that does not blanch under pressure. In the early stages of the disease, the rash may not be present or may be atypical. If present it may consist only of a few haemorrhagic spots located in a place such as the groin or feet (see Section 2.2). Meningococcal disease may have clinical features not normally expected in children with acute systemic illnesses (see Section 2.2). Practitioners should ensure that a patient with a systemic febrile illness, particularly a child, can be promptly reassessed should the need arise within 4-6 hours (see Section 2.2). All general practitioners should have benzylpenicillin in their surgeries and emergency bags, and should be ready to administer it immediately to patients with a systemic febrile illness and a petechial or purpuric rash (see Section 2.3). The doses are: - children aged < 1 year — 300 mg; - children aged 1–9 years — 600 mg; - adults or children aged 10 years or over — 1200 mg. ( this can be administered Intravenous or intramuscular) The early administration of benzylpenicillin on suspicion of meningococcal disease, followed by urgent transfer to hospital, can be life saving. Ceftriaxone is a suitable alternative if available. If clinical suspicion exists to warrant a referral for admission to hospital the patient should receive benzylpenicillin prior to transfer. A history of a rash following penicillin is not a contraindication for benzylpenicillin. If definite contraindications to Penicillin refer to the infectious disease Physician on call. The local public health unit should be notified immediately to enable an appropriate public health response Prior to transfer to an Emergency Department , advise the receiving hospital of patients condition or referral Classic signs Haemorrhagic rash, meningism, impaired consciousness Median onset 13–22 hours Newly identified signs and symptoms in children under 16 years of age Leg pain, cold extremities, abnormal skin colour Median onset 7–12 hours Version One February 2012 Page 3 Early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia HNELHD CG 12_TBA Important Points for Consideration in Hospital Care If a patient has clinical signs or symptoms suggestive of invasive meningococcal disease (meningitis or septicaemia) they should be given parenteral antibiotics immediately (see Section 3.3) and triaged appropriately to expediate care Deferral of lumbar puncture may be appropriate (see Section 3.5.1). Therapy should not be delayed while awaiting results of diagnostic tests, such as a lumbar puncture or computed tomography (CT) scan. All patients with suspected meningococcal infection should have blood collected as soon as possible for Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and culture, and blood for neutrophil and platelet counts. If petechiae are present or if frank bleeding is evident, formal coagulation studies should be undertaken. Treatment should be guided by the latest version of the Antibiotic Guidelines. These may be accessed through the link provided. http://proxy9.use.hcn.com.au For many patients, the severe sepsis guidelines need to be followed rather than the meningitis. Specimens used for the diagnosis of meningococcal infection Blood for culture and PCR Aspirate from sterile sites for microscopy, culture, PCR as appropriate Aspirate from skin lesions for microscopy, culture and PCR (though this is not validated) CSF for microscopy, culture, PCR Meningococcal septicaemia often occurs without meningitis. In these cases the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may be normal. Where evidence exists for increased intracranial pressure (e.g. clouded or impaired consciousness, papilloedema, focal neurological signs or vomiting), lumbar puncture should be deferred until therapy and supportive measures have been established and investigations, such as a CT scan, undertaken to define existing intracranial lesions. Negative findings on initial microscopy and biochemical examination of CSF do not exclude meningococcal meningitis. Positive cultures may be obtained in the following days. Culture of Neisseria meningitidis from a normally sterile site confirms the diagnosis. However, with early use of antibiotics and the likelihood of a negative culture, non-culture methods for diagnosis become more important. PCR tests to detect meningococcal DNA can be per formed on blood and CSF, and have high sensitivity and specificity, even when prior antibiotics have been given (see Section 4.4). Complications of meningococcal disease require appropriate discharge planning and specialised follow-up arrangements. Counselling and support for the patient, family members and health professionals involved in the care of the patient should be considered. IMPLEMENTATION PLAN Responsibility for promoting adherence to these guidelines rests with: • Area Quality Use of Medicines Committee • Clinical Directors across HNE, all Clinical Streams • Directors of Physician Training Version One February 2012 Page 4 Early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia HNELHD CG 12_TBA • Director of JMO Training • Area Infection Prevention and Control Unit Communication Plan This will include distribution to • HNE Acute Networks and Cluster Managers: thence to heads of Clinical Units • Chair of Area Quality Use of Medicines Committee and thence to other QUM/Drug Committees EVALUATION PLAN The HNELHD Meningococcal Review Committee reviews all meningococcal cases across the district for clinical compliance to the guideline which is considered current best practice. A letter is sent to the key clinicians involved in each case which highlights the key findings of the review to improve compliance to the guideline.. CONSULTATION WITH KEY STAKEHOLDERS Infectious Diseases Physicians Clinical Microbiologists, HAPS Emergency Medicine, Clinical Stream Population Health Clinical Governance REFERENCES Guidelines for the early clinical and public health management of meningococcal disease in Australia Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing October 2007. May be accessed electronically: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/cda-pubs-other-mening-2007.htm eTG complete antibiotic guidelines can be accessed at: http://proxy9.use.hcn.com.au Version One February 2012 Page 5