The "Napoleon" of Ancient Egypt (throne name Men

advertisement

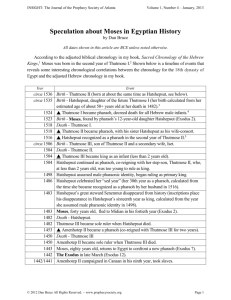

The "Napoleon" of Ancient Egypt (throne name Men-kheper-re). After the death (or removal) of his stepmother Hatshepsut, Tuthmosis III finally claimed his rightful inheritance of the throne of Egypt. During Hatshepsut's revolutionary reign, Tuthmosis III had been kept well in the background. A keen and successful military campaigner, it is now a considered possiblity that he spent a lot of this time "away" with the army. To further complicate the already confusing family tree, Tuthmosis was married to Neferure, who was the daughter of Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis II. However, Neferure had died (or disappeared?) before Tuthmosis finally succeeded the throne, which meant that he was a widower when he actually became king. He then married Hatshepsut-Merytre as his principal queen, who was to be the mother of his heir, Amenhotep II. Egyptian control of various city-states in the Syria-Palestine and Lebanon regions had slipped during the reign of Hatshepsut. Several local princes had transferred their allegiance from Egypt to the Kingdom of Mitanni, one of Egypt's most powerful rivals in western Asia. However, Tuthmosis III was to "set the record straight" with these city-states within the first two years of his independent reign. Tuthmosis's military campaigns Famous for his many successful military campaigns, Tuthmosis has earnt himself the nickname of the "Napoleon of Ancient Egypt" with some modern day egyptologists. Some of his biggest victories came against the Mitannian empire. He captured and gained control of many Mitannian territories, which expanded his power over northern Palestine and Phoenicia. He erected a stele at he Euphrates River to mark the boundary of the Egyptian Empire. In the second year of his reign, Tuthmosis began his Near Eastern campaign. This proved to be a masterpiece of planning, skill and nerve. In under five months, he had travelled from Thebes right up the Syrian coast, captured three cities, and returned to celebrate his victories. Tuthmosis launched campaigns into Syria-Palestine every summer for the next 18 years, finally capturing Kadesh. The Lists at Karnak detail over 350 cities that fell to the mighty troops of Ancient Egypt. Apart from the 17 campaigns into Syria-Palestine, the king also mounted small expeditions into Nubia, building temples at Amada and Semna. Many temples were enriched, embellished and extended from the spoils of war, in particular, the temple of Karnak. A great black granite "Victory Stelae" from Karnak records how the "king smote all before him". Pylon 7 records his successful military campaigns, and shows the king in the ever popular style of Pharaoh smiting his enemies. Will we ever know the truth about Hatshepsut and Tuthmosis III? It was originally believed that Tuthmosis III had waged a vengeful war on his stepmother's monuments when he had finally became pharaoh in his own right. After the death or removal of Hatshepsut, many reliefs at her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahri were badly damaged, and statues were smashed. Even the tombs of Tuthmosis's stepmother's courtiers suffered attacks. Hatshepsut's obelisks, which had been brought from Aswan to Karnak were walled up and their inscriptions hidden. Ironically this preserved them in excellent condition, and they have since been revealed once again. However, it is now thought more along the lines that the monuments were not actually defaced until many years later. This of course, raises the questions: Was the motive for the destruction and defacement of the monuments pure vengeance and anger on the part of Tuthmosis III, or possibly more of a feeling that Hatshepsut's reign had simply been contrary to tradition? This "break from tradition" may have also been the reason why she was omitted from subsequent King Lists, in the same way that Akhenaten, Smenkhkare and Tutankhamun were. Why would such a great military campaigner such as Tuthmosis III, who achieved so much during his reign, seemingly allow his so called "hated" stepmother to rule for such a significant number of years when the throne should have rightfully been his in the first place? It is by no means clear as to whether Hatshepsut simply died, and Tuthmosis III then became sole ruler, or whether she was forcibly removed. Senemut, Hatshepsut's architect, chief courtier and tutor to her daughter Neferure was not mentioned after Tuthmosis's 19th regnal year. It is possible that Senemut's political skills had helped Hatshepsut to gain her elevated position, and that his disappearance may have eased the transfer of power to Tuthmosis III. Perhaps one day, the true complexities of this relationship will finally be discovered! http://www.egyptologyonline.com/tuthmosis_iii.htm Great Lives from History: The Ancient World, Prehistory-476 C.E. Thutmose III BORN: Late sixteenth century B.C.E.; probably near Thebes, Egypt DIED: 1450 B.C.E.; probably near Thebes, Egypt EGYPTIAN PHARAOH (R. 1504-1450 B.C.E.) During a reign of nearly fifty-four years, Thutmose III consolidated Egypt’s position as primary power in the ancient Near East and North Africa. He laid the groundwork for some two hundred years of relative peace and prosperity in the region. AREA OF ACHIEVEMENT Government and politics, war and conquest EARLY LIFE Thutmose (THUHT-mohz) III, son of Thutmose II and a minor wife named Isis, became the fifth king of Egypt’s Eighteenth Dynasty (c. 1570-1295 B.C.E.) while still a child. It is very likely that Thutmose III was not the obvious heir to Egypt’s throne. According to an inscription at Karnak carved late in his reign, the young Thutmose spent his early life as an acolyte in the Temple of Amen. Thutmose III asserted that the god Amen personally chose him as successor to his father: During a ritual procession of Amen’s statue through the temple, the god sought out Thutmose; an oracle revealed that he was the god’s choice to be the next king. Thutmose thus became his father’s legitimate heir. The historical value of this account has been doubted. It was recorded late in Thutmose III’s reign. Furthermore, it closely parallels an earlier text describing the accession of Thutmose I. Whatever the historical value of this account for determining the legitimacy of Thutmose III’s claim to succeed his father, he did ascend to the Egyptian throne on the death of Thutmose II. Contemporary inscriptions make clear, however, that during the first twenty-one years of the reign, real power was held by Hatshepsut (c. 1503-1482 B.C.E.), the chief queen or Great King’s Wife of his father. The relationship between Thutmose III and Hatshepsut in these early years has been the subject of scholarly controversy. By year 2 of Thutmose III’s reign, Hatshepsut had assumed all the regalia of a reigning king. Yet it is not at all certain that she thrust Thutmose III into the background in order to usurp his royal prerogative, as early twentieth century commentators have claimed. Hatshepsut probably crowned herself coregent to obtain the authority to administrate the country while Thutmose III was still a minor. Hatshepsut’s year dates are often recorded alongside dates of Thutmose III. There is also evidence that his approval was necessary for significant decisions such as installing a vizier, establishing offering endowments for gods, and authorizing expeditions to Sinai. In any case, there is no question that Thutmose’s early years were spent in preparation for his eventual assumption of sole authority. His education included study of hieroglyphic writing. Contemporaries comment on his ability to read and write like Seshat, the goddess of writing. His military training must also have occurred during this time. When Hatshepsut died in the twenty-second year of Thutmose III’s reign, he assumed sole control of the country. Whether it was at this point that an attempt was made by Thutmose III to obliterate the memory of Hatshepsut is open to doubt. It is clear that Thutmose III emphasized his descent from Thutmose II as part of the basis for his legitimate right to rule Egypt. The mummy of Thutmose III reveals a man of medium build, almost 5 feet (1.5 meters) in height—for his time, he was relatively tall. He appears to have enjoyed good health throughout most of his life, avoiding the serious dental problems common to other Egyptian kings. LIFE’S WORK Larger version (55K) Head of the mummy of Thutmose III. Head of the mummy of Thutmose III. (Library of Congress) The ancient Egyptians expected their pharaoh’s career to follow a preconceived pattern that was ordained by their gods. This pattern was always followed in the historical texts that the Egyptians wrote describing the accomplishments of their kings. There is good reason to believe that Thutmose III became the prototype for a successful king. His achievements were emulated by his successors throughout most of the New Kingdom (c. 1570-c. 1069 B.C.E.). The pattern included conquests abroad, feats of athletic prowess, and building projects at home. Between the twenty-third and thirty-ninth years of his reign, Thutmose III undertook fourteen military campaigns. These campaigns are documented in a long historical text carved on the walls at the Temple of Karnak, called the Annals. Various stelae (inscriptions on upright slabs of stone) found in other Egyptian temples also provide information on his career. The most significant campaigns occurred in year 23 and in year 33 of his reign. The campaign of year 23 was fought against a confederation of Syro-Palestinian states led by Kadesh, a Syrian city-state on the Orontes River. The forces allied with Kadesh had gathered at a city called Megiddo on the Plain of Esdraelan in modern Israel. The Egyptian description of the battle that took place in Megiddo follows a pattern known from other inscriptions yet contains many details that attest its basic historical value. Thutmose III set out for Syria-Palestine with a large army. On reaching the town of Yehem, near Megiddo, Thutmose III consulted with his general staff on tactics and strategy. The general staff urged caution on the king, suggesting that the main road to Megiddo was too narrow and dangerous for the Egyptian army to pass safely on it. They argued for an alternative route to Megiddo that would be longer, yet safer. Thutmose III rejected his staff’s advice, judging that the bolder course was more likely to succeed. The staff acceded to the king’s superior wisdom; the Egyptian army proceeded along the narrow direct path, surprised the enemy, and encircled Megiddo. The enemy emerged from the city only to be routed through Thutmose’s personal valor. As the enemy retreated, however, the Egyptian forces broke ranks and fell on the weapons that the enemy had abandoned. This unfortunate break in discipline allowed the leaders of the Kadesh confederation to escape back into the city of Megiddo. Thutmose was forced to besiege the city. The siege ended successfully for the Egyptians after seven months, when the defeated chieftains of the alliance approached Thutmose with gifts in token of their submission. This total defeat of the enemy became synonymous in later times with utter disaster. The name of the Battle of Megiddo—Har Megiddo (Mount Megiddo) in Hebrew—entered English as Armageddon, a word that designates a final cataclysmic battle. Thutmose was equally wise in his handling of the defeated chieftains as he had been in war. The chieftains were reinstalled on their thrones, now as allies of Egypt. Their eldest sons were taken back to Egypt as hostages to guarantee the chieftains’ cooperation with Egyptian policy. As the various Syro-Palestinian rulers died, their sons would be sent home to rule as Egyptian vassals. These sons, by that time thoroughly trained in Egyptian customs and culture, proved to be generally friendly to Egypt. Thutmose’s ambitions for Egyptian imperialism extended beyond Syria-Palestine. In the thirtythird year of his reign, he campaigned against the Mitanni, who occupied northern Mesopotamia (modern Iraq), the land the Egyptians called Nahrain. This battle also demonstrated Thutmose’s mastery of strategy. He realized that his major problem in attacking the Mitanni would be in crossing the Euphrates River. To that end, he built boats of cedar in Lebanon and transported them overland 250 miles (403 kilometers) on carts. Once again, the element of surprise worked in Thutmose’s favor. He was easily able to cross the river, attack the enemy, and defeat them. Thutmose demonstrated his athletic prowess on the return trip from Nahrain. He stopped in the land of Niy, in modern Syria, to hunt elephants as had his royal ancestors. His brave deeds included the single-handed slaughter of a herd of 120 elephants. Thutmose was responsible for initiating a large number of building projects within Egypt and in its Nubian holdings. The chronology of these projects is not understood in detail, but it is clear that he either built or remodeled eight temples in Nubia and seven temples in Upper Egypt. In the Egyptian capital of Thebes, he built mortuary temples for his father and grandfather as well as for himself. He added important buildings to the complex of temples at Karnak. These projects included the site of the Annals and a temple decorated with relief sculptures showing the unusual plant life Thutmose had observed during his campaigns to Syria-Palestine and Mesopotamia. Though it is difficult to identify the plants that interested Thutmose and his artists, this unusual form of decoration for a temple illustrates the king’s interest in scholarly pursuits. Thutmose’s foresight included planning for his own successor. In the fifty-second year of his reign, his son Amenhotep II was designated coregent. The custom of naming and training an heir to the throne while the father still lived had been known since at least the Middle Kingdom (c. 2055-c. 1650 B.C.E.). Thutmose showed wisdom in choosing as his successor Amenhotep, a son who would largely follow his father’s policies. The last twelve years of Thutmose III’s reign passed relatively peacefully. The Annals for this period record only the yearly delivery of goods for the king’s and the god’s use. Little is known of Thutmose III’s personal life. Scholars are in disagreement as to whether he ever married Neferure, the daughter of Hatshepsut. His earliest wife was probably Sit-iakh; she was the mother of Amenemhet, a son who probably died young. A second wife, Meryetre-Hatshepsut II, was the mother of Amenhotep II. Nothing is known of a third royal wife, Nebtu, aside from her name. Four other royal children are known. During the fifty-fourth year of a reign largely dedicated to war, Thutmose III died peacefully. He was buried by his son Amenhotep II in the tomb that had been prepared in the Valley of the Kings. SIGNIFICANCE Despite the clichés and preconceived patterns that characterize the sources available for reconstructing the life of Thutmose III, he emerges as a truly remarkable man. His conquests in Syria-Palestine and Mesopotamia laid the groundwork for at least two hundred years of peace and prosperity in the ancient Near East. Vast quantities of goods flowed into Egypt’s coffers from colonial holdings during this time. The royal family, the noblemen, and the temples of the gods came to possess previously unimagined wealth. The threat of foreign domination that had haunted Thutmose’s immediate ancestors was finally dissipated. Egypt looked confidently toward a future of virtually unquestioned dominance over its neighbors. Thutmose III himself was long remembered by Egyptians as the founder of their country’s prosperity and security. Succeeding kings of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Dynasties modeled their reigns on the historic memory of the founder of the Egyptian empire. FURTHER READING Goedicke, Hans. The Battle of Megiddo. Baltimore, Md.: Halgo, 2001. An in-depth analysis of the battle, including the events leading up to it and its place in Thutmose’s personal mythology. Redford, Donald B. The Wars in Syria and Palestine of Thutmose III. New York: Brill, 2003. Discusses the political and military aspects of Thutmose’s reign. Tulhof, Angelika. Thutmosis III, 1490-1436 B.C.E.: First Conqueror of the Middle East, Artist, and Multiculturalist. London: Karnak House, 2003. A popular biography portraying Thutmose’s accomplishments in modern terms. Tyldesley, Joyce A. Hatshepsut: The Female Pharaoh. New York: Viking, 1996. This well-researched, scholarly biography of Hatshepsut of necessity also covers the early years of Thutmose’s life as well. RELATED ARTICLES IN GREAT LIVES FROM HISTORY: THE ANCIENT WORLD c. 1600-c. 1300 b.c.e., Mitanni Kingdom Flourishes in Upper Mesopotamia; c. 1570 b.c.e., New Kingdom Period Begins in Egypt; From c. 1500 b.c.e., Dissemination of the Book of the Dead; c. 1280 b.c.e., Israelite Exodus from Egypt; c. 1450 b.c.e., International Age of Major Kingdoms Begins in the Near East; c. 1365 b.c.e., Failure of Akhenaton's Cultural Revival. Edward Bleiberg Thutmose III 1479 - 1425 BC) King of Upper & Lower Egypt Menkheper Ra Son of Ra Thetmess Thutmose III, (left) is my favourite Pharaoh. He possessed all the qualities of a great ruler. A brilliant general who never lost a battle, he also excelled as an administrator and statesman. He was an accomplished horseman, archer, athlete and discriminating patron of the arts. His reign, with the exception of the uncharacteristic spite against the memory of Hatshepsut, was notable for its lack of bad taste and brutality. Thutmose had no time for pompous, self-indulgent bombast and his records show him to be a sincere and fair-minded man. During Hatshepsut's reign there were no wars. Egypt’s neighbouring countries regularly paid tribute but as is often the case when a new king comes to the throne subject nations are inclined to test his resolve. Thutmose found himself faced with a coalition of the princes of Kadesh and Megiddo, who had mobilised a large army. Also the Mesopotamians and their kinsmen living in Syria refused to pay tribute and declared themselves free of Egypt. Not daunted, Thutmose immediately set out with his army and crossing the Sinai desert he marched to the city of Gaza, which had remained loyal to Egypt. The events of the campaign are well documented because Thutmose's private secretary, Tjaneni, kept a record which was later copied and engraved onto the walls of the temple of Karnak. This first campaign revealed Thutmose to be the military genius of his time. He understood the value of logistics and lines of supply, the necessity of rapid movement and sudden surprise attack. He lead by example and was also probably the first person in history to really utilise sea-power to support his campaigns. Megiddo was his first objective because it was a key point and had to be taken at all costs. When he reached Aaruna Thutmose held a council with all his generals. There were two routes to Megiddo a long, easy and level road around the hills, which the enemy expected Thutmose to take, and a route which was narrow, difficult and cut through the hills. His generals advised him to take the easy road through the hills, saying "horse must follow behind horse and man behind man also, and our vanguard will be engaged while our rearguard is at Aaruna without fighting" But Thutmose's reply to this was "As I live, as I am the beloved of Ra and praised by my father Amon, I will go on the narrow road. Let those who will, go on the roads you have mentioned; and let anyone who will, follow my Majesty" Now, when the soldiers heard this bold speech they shouted with one accord We follow thy Majesty whithersoever thy Majesty goes". Thutmose led his men on foot through the hills "horse behind horse and man behind man, his Majesty showing the way by his own footsteps". It took about twelve hours for the vanguard to reach the valley on the other side and another seven hours before the last troops emerged. Thutmose himself waited at the head of the pass till the last man was safely through. The sudden and unexpected appearance of Egyptians in their rear forced the allies to make a hasty re-deployment of their troops. There are said to have been over 300 allied kings, each with his own army, an immense force. However, Thutmose was determined and when the allies saw him at the head of his men leading them forward, they lost heart for the fight and fled for the city of Megiddo "As if terrified by spirits: they left their horse and chariots of silver and gold" The Egyptian army, being young and inexperienced fell upon the plunder of the battlefield and lost the opportunity of taking the city immediately. Thutmose was very angry, he said to them "If only the troops of his Majesty had not given their hearts to spoiling the things of the enemy, they would have taken Megiddo at that moment. For the ruler of every northern country is in Megiddo and it's capture is as the capture of a thousand cities." Megiddo was besieged. A moat was dug around the city walls and this was completed by a strong wooden palisade. The king gave orders to let nobody through except those who signalled at the gate that they wished to give themselves up. The siege lasted some seven months but eventually the vanquished kings sent out their sons and daughters to sue for peace. "All those things with which they had come to fight against my Majesty, now they brought them as tribute to my Majesty, while they themselves stood upon their walls giving praise to my Majesty, and begging that the Breath of Life be given to their nostrils" They received good terms for surrender. An oath of allegiance was imposed upon them "We will not again do evil against Menkheper Ra our good Lord, in our lifetime, for we have seen his might, and he has deigned to give us breath." Thutmose III is compared with Napoleon but unlike Napoleon he never lost a battle. He conducted sixteen campaigns in Palestine, Syria and Nubia and his treatment of the conquered was always humane. He established a sort of Pax Egyptiaca over his empire. Syria and Palestine were obliged to keep the peace and the region as a whole experience an unprecedented degree of prosperity. Thutmose III's impact upon Egyptian culture was profound. He was a national hero who was revered long after his time. Indeed his name was held in awe even to the last days of Egyptian history. Besides his military achievements he carried out many building works at Karnak. He also set up a number of obelisks in Egypt. One of which, mistakenly called Cleopatra's Needle, now stands on the Embankment in London. It's brother is in Central Park in New York. Another is near the Lateran in Rome and there is also one of his obelisks in Istanbul. Therefore, he has had an unwitting presence in some of the most powerful nations of the last two thousand years. http://www.discoveringegypt.com/k-q3.htm