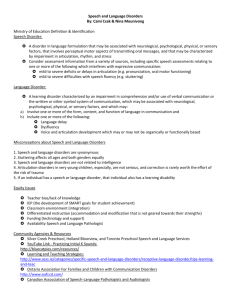

CHAPTER 1: Abnormal Psychology

advertisement

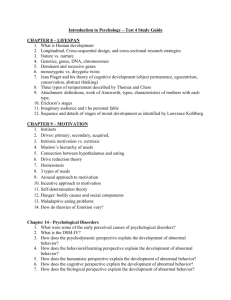

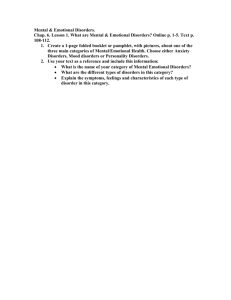

CHAPTER 1: Abnormal Psychology: An Overview Chapter Overview/Summary Encountering instances of abnormal behavior is a common experience for all of us. This is not surprising given the high prevalence of many forms of mental disorder. A precise definition of abnormality is still elusive. Even though we lack consensus on the precise definition of abnormality, there are clear elements of abnormality: suffering, maladaptiveness, statistical deviancy, violations of society’s standards, social discomfort, irrationality or unpredictability, and dangerousness. These elements allow for the adoption of a prototype model of abnormality. Although this model is helpful, we have the additional problem of changing values and expectations in society at large. Currently, the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders is in the fifth edition, a text revision that is referred to as the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). The DSM-5 has been the topic of much debate and controversy.. The definition of a mental disorder in the DSM-5 is a syndrome that is present in an individual that involves clinically significant disturbance in behavior, emotion regulation, or cognitive functioning. This definition considers these disturbances to be a result of biological, psychological, or developmental dysfunction and recognizes that they cause significant distress or disability. Moreover, the syndrome is not an expectable response to a stressor or loss, and does not result from deviating from socially acceptable norms. Despite these difficulties, psychologists continue to classify mental disorders for several reasons: classification systems provide a nomenclature that allows us to structure information in a more helpful way, research on etiological factors, treatment decisions, social and political implications, and insurance reimbursement. There are also many disadvantages to classifying mental disorders: loss of information, stigma, stereotyping, and labeling. With the influence of such things as labeling and stereotyping, it was first thought that the public could be educated that mental illnesses are indeed real disorders of the brain. This has not been the case, but with the public’s increased awareness, some of the stigma associated with mental health issues has decreased. Some interesting research has shown that although people realize the impact of neurobiology as a cause of mental illness, it does not mean that the level of prejudice has decreased. Society and culture are vital in determining what defines what is normal versus abnormal, and culture can also influence the presentation of clinical disorders. For instance, karo-kari is a form of honor killing in Pakistan wherein a woman can be murdered for disgracing her family. There are also certain disorders, such as taijin kyofusho or ataque de nervios, that appear to be highly culture specific. Additionally, beyond disorders, we have different superstitions. For example, in Christian countries the number 13 is viewed as unlucky. In Japan, on the other hand, the number four is viewed as bad because in Japanese the word for “four” pronounced in a similar manner to the word death. The DSM opts for a categorical classification system similar to that used in medicine. Disorders are regarded as discrete clinical entities, although not all clinical disorders are best considered in this way. Even though it is not without problems, the DSM provides us with a working set of criteria that helps clinicians and researchers to identify and study specific and important problems that affect people’s lives. Although it is far from a “finished product,” knowledge of the DSM is essential to a serious study of the field. The extent of mental disorders may be surprising. Several epidemiological studies have been conducted in recent years. The lifetime prevalence of having a DSM disorder is 46.4 percent. In addition, there is significant comorbidity, especially among those individuals who have severe disorders. Unfortunately not all people with mental disorders receive treatment. Some may deny or minimize their problems, and others may try to cope with their problems on their own. Even when the problems are recognized, many delay seeking treatment or seek assistance from a primary health care provider such as a physician. There are numerous forms of treatment for psychological disorders, such as medication, various types of psychotherapy, and outpatient care, but for more intensive treatment, hospitalization and inpatient care are preferred. In an ideal case, the mental health team, composed of professional and paraprofessionals, may gather information from a variety of sources, process and integrate all the available information, arrive at a consensus diagnosis, and plan the initial phase of treatment. Some examples of the different professionals in the mental health field would be clinical social workers, counselors, psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists, pastoral counselors, community mental health workers, alcohol or drug-abuse counselors, clinical psychologists, counseling psychologists, school psychologists, psychiatrists, and psychoanalysts. To avoid misconception and error, we must adopt a scientific attitude and approach to the study of abnormal behavior. This requires a focus on research and research methods, including an appreciation of the distinction between what is observable and what is hypothetical or inferred. To produce valid results, research must be done on people who are truly representative of the diagnostic groups to which they purportedly belong. Research in abnormal psychology may be observational, correlational, or experimental. Some of the identified sources of information would be case studies, self-report data, and observations. Observational research studies things as they are. Experimental research involves manipulating one variable (the independent variable) and seeing what impact this has on another variable (the dependent variable). Mere correlation between variables does not allow us to conclude that there is a causal relationship between them. Simply put, correlation does not imply causation. Although most experiments involve studies of groups, single case experimental designs (e.g., ABAB designs) can also be used to make causal inferences in individual cases. Analogue studies, also known as laboratory studies, provide an approximation to the human disorders of interest, by studying animals in the place of humans (e.g., animal research). Although generalization can be a problem, animal research in particular has been very informative. Research starts with asking a question to make sense of behavior by generating a hypothesis. The next part is to decide who should be a part of the study. This is done by using a technique called sampling, which is when people are selected who have similar abnormalities of behavior. One of the goals of research in the field of abnormal psychology is to learn the causes of different mental disorders. When assessing correlational research, it is important to evaluate the statistical significance or the probability that the correlation would simply occur by chance. The effect size is the number used to assess the association between two variables of the sample size. However, when the researchers want to review the past findings from other research studies, they conduct a meta-analysis that calculates and combines the effect sizes from the studies selected. Some strategies often applied in correlational research are either retrospective or prospective approaches. A retrospective research strategy identifies the potential factors that might have been associated with the onset of the disorder. A prospective research strategy identifies individuals that would be considered at risk for developing a psychological disorder. Detailed Outline I. What Do We Mean By Abnormality? A. The Elements of Abnormality 1. Suffering—personally defined psychological suffering (e.g., you can’t leave your house because you need to wash your hands 1,000 times). This is one of the most important aspects according to the APA. 2. Maladaptiveness—any behavior that is maladaptive for the individual or toward society (e.g., anorexia); starving oneself is maladaptive. 3. Statistical deviance—abnormal is defined as “away from the normal.” Also, just because something is statistically common or uncommon does not reflect abnormality (e.g., having an intellectual disability, although statistically rare, represents a deviation from the normal). 4. Violation of the standards of society—all cultures have rules, and some of these are viewed as laws. Those who fail to follow the conventional social and moral rules of their cultural group may be viewed as abnormal (e.g., the Amish of Pennsylvania not driving a car or watching television). 5. Social discomfort—occurs when someone breaks a social rule and then those around this individual experience some discomfort (e.g., you are sitting in a movie theater with rows of empty seats and then someone comes and sits directly next to you). 6. Irrationality and unpredictability—people are expected to behavior in socially acceptable ways and abide by those social rules (e.g., if someone next to you started screaming and yelling obscenities at nothing, this behavior would be viewed as unpredictable, disorganized, and irrational). 7. Dangerousness—this represents someone who is clearly a danger to himself or herself or to another person. This is also known as exhibiting DTO (e.g., danger to others) and DTS (e.g., danger to self) behaviors (e.g., therapists are required to hospitalize suicidal clients, but someone who engages in high-risk sports such as free diving or base jumping is not immediately considered mentally ill). 8. Deviancy—statistically unusual behaviors. Again, point out this is not comprehensive (e.g., depression is in no way statistically unusual). 9. Violation of the standards of society—this gets at failure to follow the conventional social and moral codes of an individual society (e.g., taking ones clothes off in public). 10. Causing social discomfort—related to the above violation of social norms but results in others’ discomfort. 11. Irrationality and unpredictability—related to behavior that cannot be expected and/or behaviors that appear to be irrational (e.g., washing one’s hands 1,000 times). The DSM-5 Definition of Mental Disorder 1. A syndrome that occurs in individuals and involves clinically significant disturbance in behavior, emotion regulation, or cognitive functioning. 2. Reflects a dysfunction in biological, psychological, or developmental processes. 3. Associated with clinically significant distress or disability. 4. Must be beyond the expectable response to common stressors and losses. 5. Is not primarily a result of social deviance or conflicts with society. 6. DSM-5 is a work-in-progress and has already been the subject of much controversy and debate. B. E. C. Why Do We Need to Classify Mental Disorders? 1. Advantages: a. Sciences rely on classification. b. Provides a nomenclature, a naming system. c. Enables us to structure information. d. Delimits the domain of professional expertise. e. Allows us to study different disorders. f. Lets us learn about causes but also treatment. D. What Are the Disadvantages of Classification? 1. Overall have to do with negative consequences for the individual. 2. Loss of information/detail due to the information being in shorthand form. 3. As we simplify through classification we lose personal details about the actual person with the disorder. 4. Stigma is still associated with having a psychiatric disorder. 5. Stereotyping are those automatic beliefs concerning other people based on trivial factors. For example, people who wear glasses are more intelligent. 6. Labeling—classification should be of disorders, not of people. Once a person receives the “diagnostic label,” it can be hard to lose this label even after an individual has made a full recovery. The diagnostic classification system does not classify people, but classifies the disorders that people have. For example, when previously individuals were called “manic-depressives,” this type of language shows that the person is the diagnosis. If you use more people-first language, you would state that the person had been diagnosed with manic depression. How Does Culture Affect What Is Abnormal? 1. Culture shapes the clinical presentation of disorders. F. II. Culture-Specific Disorders 1. Certain forms of psychopathology are culture-specific: a. taijin kyofusho: Japan—marked fear of giving offense b. ataque de nervios: Caribbean—distress triggered by a stressful event c. karo kari: Pakistan—a form of honor killing whereby a woman is murdered by a male relative because she has disgraced her family 2. Nevertheless, certain unconventional actions and behaviors such as hearing voices, laughing at nothing, defecating in public, drinking urine, and believing things that no one else believes are almost universally considered to be the product of mental disorder How Common Are Mental Disorders? A. Prevalence and Incidence 1. Frequencies of particular disorders are of great interest to professionals. a. Research efforts are guided by frequencies. b. Allocation of treatment resources depends upon the extent of the disorder. 2. Epidemiology—the study of the distribution of diseases, disorders, or health-related behaviors in a given population. 3. Prevalence—the number of actual, active cases in a given population during any given period of time—typically expressed as a percentage. 4. Point prevalence—at any instant. 5. One-year prevalence—during an entire year. 6. Lifetime prevalence—full lifespan—tends to be higher than other prevalence rates. 7. Incidence—a rate, specifically the number of new cases occurring over a period of time (usually one year). B. Prevalence Estimates for Mental Disorders 1. The Epidemiologic Catchment Area study: sampled citizens of five communities (Baltimore, New Haven, St. Louis, Durham, and Los Angeles). 2. The National Comorbidity Survey: sampled the entire United States. 3. One-year prevalence—based on the replication of the National Comorbidity Survey: a. 18.1 percent anxiety disorder (see Table 1.1) b. 26.2 percent any disorder (see Table 1.1) 4. Lifetime prevalence of having a DSM disorder: 46.4 percent. a. May be an underestimate as did not assess for eating disorders, schizophrenia, autism, or most personality disorders. b. Disorder with the highest lifetime prevalence—major depressive disorder (see Table 1.2). c. Although the lifetime prevalence is high, the duration may be brief or severity may be mild. 5. Comorbidity is especially high in people who have severe forms of mental disorders (50 percent) in comparison to those who have milder forms of mental disorders (7 percent). C. Treatment 1. Not all people with disorders get treatment. a. Some deny or minimize their problems. b. Some fear the stigma of diagnosis. c. Some try to cope on their own. d. Some spontaneously recover. e. Some see general practitioner physicians. f. Many delay treatment, even if they recognize they need help. 2. Inpatient and outpatient treatment a. Inpatient hospitalization is declining. b. Budget cuts. c. Even if hospitalized, stays tend to be shorter and people are referred for additional outpatient treatment. d. Effective medications. e. Deinstitutionalization (Chapter 2). f. Half of individuals with depression delay seeking treatment for more than 6–8 years. g. For anxiety disorders, the delay ranges from 9–23 years. The Mental Health “Team” (The World around Us 1.3) 1. In both mental health clinics and hospitals, people from several fields may function as an interdisciplinary team. 2. Professional a. Clinical psychologist b. Counseling psychologist c. School psychologist d. Psychiatrist e. Psychoanalyst f. Clinical social worker g. Psychiatric nurse h. Occupational therapist i. Pastoral counselor 3. Paraprofessional a. Community mental health worker b. Alcohol- or drug-abuse counselor Research Approaches in Abnormal Psychology 1. Acute—a disorder where the symptoms are short term. 2. Chronic—the symptoms of a disorder that appear long in duration. 3. Etiology—the cause of a disorder. Sources of Information A. Case Studies 1. Emil Kraepelin (German psychiatrist) and Eugen Bleuler (Swiss psychiatrist) described cases of schizophrenia. 2. Alzheimer described a case of Alzheimer’s disease. 3. Sigmund Freud described cases of phobia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. 4. Cases may be idiosyncratic and results not generalizable. 5. Bias can happen in case studies because the writer of the case study selects which information to include. 6. Generalizability—when you are able to draw conclusions about other cases when individuals experience similar abnormalities. B. Self-Report Data 1. Self-report data may be misleading but is when research participants complete questionnaires. C. Observational Approaches 1. Overt behavior. 2. Psychophysiological variables. 3. Brain imaging technology allows us to observe how the brain works. 4. Direct observation would be used, for example, if you were trying to observe aggression in children’s behavior. Observers would record the number of times children hit, bite, push, punch, or kick their peers. Forming and Testing Hypotheses 1. Hypothesis—an effort to explain, predict, or explore something that starts after a question has been developed. 2. Careful observation can suggest interpretations requiring scientific testing. 3. Cases and prior data are good sources of hypotheses. 4. Various perspectives explain the same behavior differently. 5. Causal hypotheses shape treatment strategies we use. A. Sampling and Generalization 1. Studies that examine groups of people are valued over single cases. 2. May identify multiple causes for disorders. 3. Can generalize results to other cases. 4. Sampling is the careful selection of a sub-group that is representative of a larger population for close study. a. The more representative the sample, the more able we are to generalize. D. III. IV. V. b. VI. Ideally, we would like to be able to use random sampling to avoid potential biases. c. Erroneous conclusions can emerge from faulty sampling. B. Internal and External Validity 1. External validity—being able to generalize results beyond the current study. 2. Internal validity—how confident you are in the current study’s results. C. Criterion and Comparison Groups 1. People with the disorder are the criterion group. 2. Control groups (sometimes called comparison groups)—typically healthy people—are used for comparisons. Research Designs A. Studying the World as It Is: Correlational and Experimental Research Designs (see Figure 1.4) 1. Experimental studies of etiological factors are unethical and impractical. 2. Observational research requires no manipulation of key variables. 3. Study natural groups (e.g., depressed people). 4. Correlational research design takes things as they are to see if a relationship exists between them. B. Measuring Correlation 1. A correlational coefficient statistic that ranges from -1 to +1 with a 0 in between. Correlations of +1 or -1 means the two variables are directly related. A correlation of 0 means there is no relationship between the two variables. (See Figure 1.3 for a scatterplot example.) The number, denoted by r, tells the strength of the relationship between the two variables. 2. A positive correlation means the two variables hang together—as variable A goes up or down, variable B goes up or down with it (e.g., watching violent media and committing aggressive acts, or smoking and lung cancer, or students who miss a lot of class tend to do poorly in class). 3. A negative correlation indicates that as variable A goes up or down, variable B does the opposite (e.g., having a low score in golf means you are doing well, or having a lot of money decreases the risk for schizophrenia). 4. Can provide a rich source of inference—may suggest hypotheses and occasionally provide crucial data that confirm or refute these hypotheses. C. Statistical Significance 1. P <.05 is the level of statistical significance. This indicates that there is roughly a 5 percent probability the correlation would happen by chance. The size of the correlation dictates how strong the correlation is. 2. Effect size reflects the size of association between two variables. 3. Meta-analysis is an approach that calculates and then combines the effect sizes from all of the studies. D. Correlations and Causality 1. Correlation or association of variables is not evidence of causation. a. A might cause B or B might cause A. b. A and B might both be caused by C. c. A and B are involved in a complex web of relationships with other variables. d. Third variable problem is when a third variable might be the causing both events to happen. E. Retrospective versus Prospective Strategies 1. Retrospective research strategy—memories can be both faulty and selective. 2. Such a strategy may increase the odds that investigators discover what they expect to discover. 3. Prospective research strategy—often focuses on high-risk populations before they develop the disorder. 4. Identification of differentiating variables. 5. When hypotheses correctly predict behavior, we are much closer to establishing a causal relationship. 6. Longitudinal design is a study that follows people over time. F. VII. VIII. Manipulating Variables: The Experimental Method in Abnormal Psychology 1. Scatterplots of positive, negative, and zero correlation. 2. Scientific control of all but one variable. 3. Independent variable is manipulated. 4. Dependent variable is observed for experimentally induced changes. 5. Direction of effect problem is when researchers are unable to draw any conclusions. 6. Experimental research is used to draw conclusions about causality G. Studying the Efficacy of Therapy 1. Random assignment to treated or untreated group. 2. Untreated (“waiting list”) control group. 3. Ethics of withholding effective treatment may lead to an alternative research design in which two or more treatments are compared. 4. Comparative-outcome research: comparing new versus established treatment. 5. Random assignment—every research participant has an equal chance of being placed in the treatment or the no-treatment condition. H. Single-Case Experimental Designs 1. Many observations of one subject. 2. ABAB design. 3. Single-case-research design—the same individual is studied over a period of time. I. Animal Research 1. Permits experimental manipulation. 2. Ethical considerations still apply. 3. “Analogue” of human conditions. 4. Findings from animal research provided impetus for learned helplessness model of depression. 5. Analogue studies may involve humans but are used when animals are studied to find an approximation to how something would apply to humans. The Focus of This Book A. A Scientific Approach to Abnormal Behavior 1. Clinical picture 2. Causal factors 3. Treatments B. Openness to New Ideas 1. Biological 2. Psychosocial (e.g., psychological and interpersonal) 3. Sociocultural (e.g., culture and subculture) C. Respect for the Dignity, Integrity, and Growth Potential of All Persons Unresolved Issues: Are We All Becoming Mentally Ill? The Expanding Horizons of Mental Disorder A. There Is Constant Pressure to Expand DSM to Encompass More 1. Economic interests of mental health professionals support expansion. 2. For instance, “caffeine use disorder” and “Internet gaming disorder.” B. Too Much Expansion Would Make DSM Scientifically Useless Key Terms ABAB design abnormal psychology acute analogue studies bias case study chronic comorbidity comparison or control group correlation correlational research correlation coefficient criterion group dependent variable direct observation direction of effect problem effect size epidemiology etiology experimental research external validity family aggregation generalizability hypothesis incidence independent variable internal validity labeling lifetime prevalence longitudinal design meta-analysis negative correlation nomenclature 1-year prevalence placebo treatment point prevalence positive correlation prevalence prospective research random assignment retrospective research sampling self-report data single-case research design statistical significance stereotyping stigma third variable problem