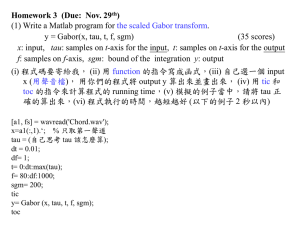

Growing up in ACS Part2 - acs-seremban

advertisement

Growing up in ACS – Part 2 Having learnt many lessons about sex from the two Michaels, I proceeded confidently to live out life. This story is about growing up in Seremban with some of my bosom buddies. It’s going to be a long yarn, so better go pee first. Washed your hands? Good, let’s get started then. Mother had nine children and my father was always trying to stretch the budget. Being the youngest, I had to wear everything handed down. That included books, shirts, and trousers; sometimes even good fitting shoes. But father was not totally unreasonable. He instructed my mother, "Tai foo hmn tak chow wai pai. Mai sun keh!" (Underwear cannot simply give all over the place. Give the boy new ones) That was a relief. My eldest brother, Kong Kee was always scratching himself down there, so I was glad not to inherit his. But poor mum was running a tight ship on a deficit budget. She was an incorrigible mahjong player always losing, so buying underwear was a bargaining session along the thoroughfares of Lee Sam Road, up and down the narrow lane. She would march into one stall, bargained until the cows came home, and then throw them back saying, "Lay kum kwai keah. Chair!" (You so expensive, what lah) and then hold up her chin and beat her fat legs to the next stall. We did this several times, and soon I became quite schooled at bargaining. Mother then left me to shop on my own. My favorite stall was at the front end of Jalan Lee Sam, adjoining Carew Street. But one day, I accidentally discovered that the two sisters, Loh Kean Pow and Low Kean Peng had a family stall there, so I stopped over. Bespectacled Kean Peng was in my class and not at all bad looking, so there was no harm in being friendly. Although quiet, she was well built, but not too big for a skinny skeleton like me. She was a reasonable compromise between the ‘tank’ Sze Poh droved around the whole day, and the daintiness exuding from the likes of Tian Siew Yin. She didn’t drive me crazy or anything like that; but beggars can’t be choosers and I thought that perhaps some experience with the opposite sex couldn’t do a young man much harm. After all, we must all begin somewhere, so my favorite maxim: ‘Who knows tomorrow what the wind may bring?’ can mean only a brave heart can win a fair lady. Old man Low was quiet, but watchful. He gave me ample time to pick my selection of ‘crocodile’ brand. Skinny as a bone, I could only manage size ‘12’ in those days. Holding one pair up, I asked: "Keh thor loi eh?" (How much?). He replied, "Sea kock!" (Forty cents!). I was shocked. All I wanted was a pair of briefs, but this man--the father of my Kean Peng--was asking me to show him my ‘kock’! Face red as chilly, I moved defensively away quickly and darted across to the next row. At about this time, I had started to use ‘Tancho’ for my hair, but I had secretly been dowsing myself down there with an expensive bottle of ‘Silverskrin’, a hair growth hormone treatment. It was an impressive bottle, distilled under a secret formula at a laboratory in London, and only available in Seremban at the only pharmacy in town over Birch Road. The lady pharmacist there had assured me it worked, and soon I was spending more than half a month’s allowance on each bottle. Each bottle could last only three weeks if applied sparingly, so it had better work. I had told her that I wanted to grow more hairs only, so she thought I was dropping hair on top. Actually, I was only interested in sprouting more hairs at the bottom, to look manlier, like the likes of Michael Lee. With careful application twice a day, once before school and once at night before going to bed, the groin region was finally managing small sprouts; nothing much, but it was at least making some show of manhood. I thought it sick for anybody to expect me to show anything until at least more of my lawn was covered. On the opposite row, old lady Low was sitting on a wooden chair. Hoping that I might get into her good books if I mentioned that I knew her daughters, I said: " Ah Soh, ngor hai lay gnor looi keh thong hook lay kher. Gnor theay hai ACS took sea yat chai. Lay leong gnor looi hoo pan nai." (Madam. I go to school with your daughters at ACS. Your daughters, very obedient) All she did was reply, "hmn…hai mayh?" (hmn…is that true?) Hoping to impress further, I piled up half a dozen of underwear, some high quality tshirts, a bottle of Tancho, a comb and a few other items which I really didn’t cared very much about--so long as Mrs. Low felt impressed I have money. "Ah Soh, yee tit su mar keh thor loi eh?" (Madam, all these, how much?) She stood up, shifted her figures through the pile and started counting, at first loudly, then softly some mathematical incantations I couldn’t hear, "Sea kock, sea kock…(inaudible mutterings…) look khow! Beah gnor look khow! Now you must understand that I am a Cantonese and she, a Hakka. The Chinese may have a common tongue and language, but scores of different dialects. A slight inflection of the tongue can carry an entirely different meaning. With 4 octave sounds to a word, a word with the wrong inflection can easily be misunderstood as having another meaning. A Hakka is unlikely to pronoun Cantonese correctly, so a slight variance in intonation often can be misunderstood by a Cantonese. At the converse, a Cantonese speaking Cantonese to a Hakka may be equally misunderstood, even if all the intonations and inflections were perfect. What she meant was, "Forty cents, forty cents…(inaudible mutterings…) six dollars! Give me six dollars!" What I heard was " show kock, show kock…(inaudible mutterings…) the thing! Let me see your thing!" Terrified now the mother also wanted to look at my thing like the old man did, I immediately responded: " Look Khow em tak lah. Gnor em tak baei lay look khow" (My thing to show you, cannot. I cannot show you my thing) A Hakka who does not speak Cantonese as her own mother tongue could have misunderstood it as, "six dollars too high, I cannot offer you six dollars." So she retorted back, " Mouw look khow, hmn tak lah. Lay hai ghor keh looi pung yau leh kerh, lay mouw baie gnor taei touw look khow hmn tak keh!" (No six dollars, cannot. You are my daughters’ friend. If you don’t give me six dollars, you don’t give me face!) To me it meant, " If you don’t show me the thing, cannot. You are after my daughter, if you don’t show me your thing, cannot!" I panicked and apologized, " Em kam kau… em kam kau… tooi hmn chi" (Sorry Madam, Sorry! I won’t mess around your daughter anymore!) She heard, " Five ninety…five ninety. Sorry I can only offer you five ninety, not six dollars!" So she responded, " Em kow kau…em kow kau…ok lah. Yee bai, ok lah. Tai bai hmn tak ker!" (Five ninety…five ninety…ok lah. This time I can give you for five ninety. Next time, cannot, just this time!) I heard, " Dare not play with my daughter? Dare not play with my daughter? Huh! This time, I’ll let you off. Next time it won’t be so easy!" Then she stretched out her hands, seeking six dollars. I thought she was offering me a hand in forgiveness, so I clutch it with both my trembling hands, shook it apologetically, head facing down respectfully, and then, with my tail behind my back, ran out off the stall! She thought she had lost a young man for a customer and was confused because she had accepted my bid of $5.90 instead of $6.00. I thought she had forgiven a possible suitor, and was lucky to preserve embarrassment by not showing her my scanty patch of undergrowth, and fled! I steeped out to the pavement and never returned. Years after leaving school, I bumped in Foo Chee Seng, the tall, dark and handsome fellow from 5A. Chee Seng was always a relaxed kind of chap; so it was not uneasy to kick start a conversation. We started talking about our family, then kids, then I enquired, "by the way, Chee Seng, who did you finally marry?" He said, " Low Keng Pow." My head kicked backwards in quiet amusement: at once I knew he must have bought a lot of underwear from Jalan Lee Sam. Old man Low and his wife must have also asked him the same things they’ve asked me and he must have impressed greatly to be accepted a suitable suitor for one of the daughters! Chee Seng may look skinny; haggard even at times, but he must have carried dynamite under his pants. More important, he had the audacity to flaunt it. On the other hand, I was a coward. I was nothing more than a miserable coward. If only the darn ‘Silverkrin’ hair tonic had worked: who knows what the wind may have brought? The champur stall in Seremban was our version of ‘Coffee Beans’ today. It was first sited opposite Rex under a makeshift canopy that leaked heavily when it rained, before it found a new home over a cement pavement strapped across Lee Sam River. It was the place then: if you want to find your friends, go to the champur stall; if your heart’s desire is to observe busty convent girls, go to the campur stall! Life was cheap then; 10 cents a small cup, 20 cents could effectively be a meal replacement! The stall was a partnership between "Lulu", "Fay Loh", "Sau Loh" and grandma, "Ah Poh." They were nice people, always smiling when it comes to serving, but stern when collecting. They had good reason, for many schoolboys just drank and ran away without paying. My favorite drink costs 10 cents. It was yellow peaches in syrup. For 10 cents, you’ll get two pieces of Australian peaches. But cost soon started to mount, and cheapskate Sau Loh started slicing one peach into two, and then soon, three! The drink soon arrived miserable looking, but as I couldn’t resist peaches, I drank it anyway. One day, I ordered my favorite peaches. My table was the nearest to the ice-grinding machine and Sau Loh was busy slicing my yellow peaches. Sau Loh was a skinny bag of bones; there was nothing prominent about him except that he had a big protruding nose. Two bunches of hairs fell from under his nose like used brooms. That day, with flies buzzing about him, he was having a hard time coping with the furious orders. Then my eyes froze. I saw him swat one fly with his left, and another with his right. Then he wiped the dead flies off his messy looking apron, dug his little finger into his nose to relieve possibly an itch, blew a few times his runny nose over a closed fist, and careless went back to slicing my peaches. Yukks! Pure poison was coming to my table! When the drink arrived on my table, I was about to run. But then sauntered in Swee Khoon, fresh from games. He was sweating like a pig inside an oven, so I audaciously pushed him a poisoned opportunity. "Swee Khoon, finish this please. I am late; I’ve got to run! I had a few earlier and people are expecting me for table-tennis in Gurney Boy’s Club!" "You spend me, huh?" "Of course", I said. "What are friends for?" 10 cents was a lot of money to me those days as it was half my day’s allowance, but the sight of my dear friend pouring alafly-nose-peach poison into his big mouth was something worth dying for. I sneaked back across to the Low family stall I had avoided for so long, stood at their front porch, and watched. Every gulp Swee Khoon took was pure ecstasy. Soon after that day, I switched over to ‘champur hank tong, cheng hai jagung’. It was a delight able devil; frosty ice with thick, rich coconut suntan covered over by black sugar, topped with a spoonful of maize. I knew the place was dirty anyhow, so I killed my basic instincts and decided that if I had to drink from this waterhole, I might as well pretend not to know what went in. Over the years, our sessions at the champur stall became longer and longer. For some, it was almost like a second home. Our patronage was well respected and some like Swee Khoon soon even had a credit account. Being young and inexperienced, managing credit soon became a problem. Worse, some of us drank more than we had money. Soon, some of us began totaling unpaid bills of more than a dollar. Lulu was very quick with her little book, and the credit risks that did own up, received stern warnings. Lulu would yell: "Lay chang kgor kum tor, chung shiong yum maey. Hmn tak!" (You owe so much; still want to drink, huh? No way!) On some days, the situation was even more tensed. When we sat down we would be greeted rather tersely. "Lay daey taei doew saey fay hark kwai mouw?" ( Did you see that fat, black devil?) We all knew whom he was referring too. Tiew Seng would say, " Mouw er. Laey khum ghock, heh ter hmn kam yum. Neigh! Heh huih gnor douw," (you so fierce, he dares not drink here. He’s there!) His fingers would point down to a dark, shadowy figure some 15 stalls away, sitting all alone in Small Boy mother’s stall. It was quite a distance but the shadow was unmistakable. Small Boy mother’s stall had become a refuge for those who could not find a seat, or was running away from Lulu. "Khor ghor saey fay loh leh. Chang gnor chin chow hmn kam leh yee toew yam. Taei tow hui ker saey hark mean choew sui leh!" (This fat devil. Owes me money then dare not drink here. I curse his dead black face!) We would laugh. But very soon we were also ourselves racking up high bills, so we have to do something, or be a fugitive as well. One day, some smart aleck noticed that unlike Lulu (who kept a book), Ah Poh had a clumsy memory, and no book. Being old, she was also hard of hearing. So we began to capitalize on this by ordering a lot, and drank so much so that when a new batch arrived, the old lady was forced to clear the previous empty cups off the table before placing new ones. When asked to pay beforehand, Tiew Seng would say: " Ah Poh! Gnor theay ter maey yum sai. Lay kaeng knor theay chow mayh?" ( Ah Poh, we haven’t finished yet. You scared we run?) He would then dig into his shirt pocket; pull up a dollar note slowly just enough to reveal the tip of the old Agung’s face. The old lady would back off because she respected Agung, especially the printed version. Besides, Tiew Seng was thought an officer and gentlemen (resplendent always in his scout’s uniform, he had badges lined even below his armpits!). After all, everyone knew his father owned a credit company in Seremban and the son was considered a smalltime ‘tai koh’ himself. So whenever it was time to count, we would call only Ah Poh, then start talking fast and loud between ourselves to confuse her. Our buzzle added to her woes for she could not concentrate. The clumsy old fool would find concentrating difficult and would yell back: "Moe choou! Lay thaey moe choou! Gnor kaey hmn toew!"(Quiet! Quiet! I can’t concentrate on the count!) We of course ignored her completely and spoke even louder, creating a din jarring to her ears. Her fingers would go round and round like a dreamer counting sheep and she’ll almost always ended short, forgetting about the previous cups she had cleared earlier! People who smoke those days were perceived generally as gangsters. And very few people did. Michael Lee, Kim Fui, Tiew Seng and some others managed to puff a whiff or two during scout camps, but it was more to keep the mosquitoes away than addiction. It was not these Vin Diesels who taught me to smoke. Both my maternal and paternal grandmothers did. Old grandma over my mother’s side lived in a dark, dank house in Klang, filled with clocks. My grandfather was a clock smith and so were all his sons. My uncles usually spend their mornings winding dozens of clock throughout the house. The house, in return, chimed by the hour. In grandma’s house it was impossible to get sleep long, for all four corners of the house ‘trembled’ with 80 odd chimes every hour. When it does, one could feel like being hit with 80 unevenly timed bells, all in a cacophony of pitches, by the hour. Under the above circumstances, Grandma had problems sleeping and would sit up late nights. To suave the pain, she puffed hand-rolled cigarettes. With infinite patience, grandma would roll tobacco over a thin piece of white paper. The paper was super thin, easy to maneuver in the hands of an experienced tobacconist. Over the years, Grandma’s fingers had become brown from rolling too much tobacco and her teeth, dark browned from all the inhaling. They say that curiosity killed the cat, and curiosity had the better of me. Often, I would watch with fascination the procedure of tobacco rolling. Once, grandma tempted me a puff and I felt funny; but a puff wasn’t enough to satisfy this cat. So one night, when everybody was asleep, I sneaked downstairs to dig for tobacco. I thought of inviting my cousin, Foo Chee Keong as an accomplice, but he was sound asleep. Chee Keong was a clumsy collection of bones, who walked as if he had no backbone constructed for a spine. Easily excitable, I could just be inviting trouble. Besides, his spectacles were thicker than the windshield of a car, and this blind bat was likely to trip himself all the way downstairs, resulting in two heads rolling instead of just one. When I reflected upon the uncoordinated strides from his walk, with both hands fluttering aimlessly about, I decided he would make a lousy tobacco thief. So I left him out. It was easy to find the brown box near the altar. But it was pitch dark without torchlight, so rolling the darn sticks was more difficult than I originally thought. I got greedy and in haste, stuck more paper wafers than needed, packed in a lot more tobacco than desired and then, sneaked away. In my hurried carelessness, the result was startling: the cigarette I had planned looked more like a giant cigar than a mild hand-roll. As grandma’s house was filled with people, the safest place to light this dynamite was the toilet. Squatting under half moonlight, I lit the ‘giant cigarette’. Since I was already in the toilet, I thought I might as well shit and kill two birds with one stone. Then, all the clocks in the house chimed!! The darn rocket was just starting to bellow like a chimney--my eyes all blinded by smoke, and the clocks chimed! The cacophony of clocks chiming together was unexpectedly and it broke a rash all over me. I dropped the giant cigar. It landed near my ding-dong, got caught in the small undergrowth. The giant cigar singed me a little, and I damn near shouted in pain. Covering my mouth in panic, I looked down: the bush that I had so carefully manicured with ‘Silverskrin’ glowed like the Flame of the Forest! Luckily, for me, the tree was not burned! My smoking days in Klang was immediately over. The tree preserved, I went home. But back in Seremban, another lesson was about to begin. My father’s mother did not smoke at all. But she prayed twice a day religiously. She would light a thin 10-inch long rolled-up brown paper that looked like a long thin cigarette and go about the house lighting up joss sticks. Back in those days, the toilets in Seremban town were just a small room with a big hole and a large pot below. The truck comes twice a week, Wednesday and Sundays, so in-between those days; everybody had to make sure they didn’t shit too much. If you do, the bucket can overflow. With 12 people in the house, managing a communal schedule for shitting is not an easy job. The pot would fill up with every new deposit, and it can be quite stressful to see heaps of shit below while you are releasing intense valve pressure from your bottom. By Tuesday of every week, the little 3 feet by 4 feet room would become a giant cesspool, smelly as hell! Flies would accompany you to the job. Occasionally, little white maggots would crawl to the floor from the bucket below and they too, will be ardent pen pals to flies. So shitting in Carew Street required tolerance and some balancing skills. But grandma was not unsympathetic. She knew that those that came from the newer flush system would find this cesspool impossible to use. So when some of my school friends visited me and had to shit, she would twist off half a rolled-up lighting paper and pass that to me, together with a box of matches. But this privilege was restricted to only a few boys she liked. Other boys who visited me and had no smoking privilege so accorded, had very uncomplimentary things to say: " Sze tho. Sze thong mouw tat teng! Youw yin mouw? (Sze Tho, toilet indescribable, got cigarette?) But of course, the specially rolled-up stick was not for everyone, only those grandma liked. Swee Khoon and Chin Teng were regular Jin Rummy ‘kakis’ but not in grandma’s favored list, so if they had to shit, they have to do so without her special cigarette. Sing Kow, Seng Keong, Su Thai Seng were all regular visitors, but they would pee, never shit. Chan Foo Yau and his brother, Chan Thong Yau played mahjong with me for several weeks at one stage, but they made sure they sat on their own ‘throne’ at home before coming over. Some unlucky friends that went in flew out quickly! "Sze Tho, beh tahan! Damn smelly, where else to shit?" When I told them that this was it, they would grab their belly, curse me, jump on their bicycles and then pray to God for home on time. Many didn’t. Others who couldn’t make the trip home would attempt to shit in our shit hole anyway, come what may. They would squat quickly, and keep two hands to the nose. The problem came when they had to wipe their arse. One hand on the nose and one hand to wipe the arse required dexterity and skill, and that could not be developed on a rush job. So many ACS friends who banked in my shit hole went home immediately after their deposit, but walked slowly, and cautiously. Some would have a queer Donald Duck walk to their gait and avoided the bicycle saddle all the way home. I never asked why. The girls who came to my house in Form 3 for Malay tuition could have included Lim Boon Chan, Lee Meng Yin, Ng Pooi Fun, Kwan Sze Poh and Kuan Loy Chin, but it was such a long time ago, I am unsure whether this list is correct. But I am sure of one thing though: they will never shit in number 18, Carew Street! Emptying your bowels can become tolerable with a ‘makeshift’ cigarette, as the smoke camouflaged the pungent smell inside the small room. In time to come, I got accustomed to the smoke-and-shit regiment and found shitting to be relatively comfortable. My tolerance swelled with practice, so much that I was even able to study, smoke and shit at the same time. With my small black pocket-sized Collins English Dictionary as a companion, I would squat an hour or two in the loo, light up a stick, and start memorizing English! *1. Years later, when I had my first two children, I took them to my old school. I showed them around. My proudest moment came when my daughter of eight spotted my name, "School Editor, 1971—Sze Tho Kong Chian’ carved in wood, mounted on a wooden board hung 12 feet outside the hall of fame. Shan Lin enquired, " Dad, how did you become the School Editor. Tell me?" I said, "It’s a long story. It started as a fire that singed the Flame of my Forest. The leaves glowed, but the tree was saved, or we could not have you!" She was barely eight; I didn’t want to talk to her about smoking or confuse her with what was a Flame of the Forest. The story has not unfolded until today*2. But the people who really taught me how to puff *3 were not both my grandmothers. It was Edward Lim and his lady friend. In those days, Edward was simply known as Lim Tau Boon. Tau Boon had just returned from Canada in 1980. Fresh from university, Tau Boon was the Assistant Manager of Malaysia Hotel in Imbi Road. It was a small hotel of some fifty-odd rooms but because of its central location in Kuala Lumpur, it was our gang’s favorite drinking hole. Now Tau Boon is what I would call an officer and a gentleman. Clean-shaven, always decorous, he kept his Boy’s Brigade march in his stride to a minimum. Being in the hotel business, he had a warm handshake, but unfortunately a smile that betrayed shyness occasionally. But he was our top gun for gambling rooms, for drinking, for other nefarious activities. Tau Boon was an incredibly decent fellow, and would seldom refuse anything to anyone if the request were not unduly unreasonable. So we all met regularly, almost 3 times a week. His hotel became a favorite landmark for anything and everything sinful. One day, he called me and said there were two good-looking chicks fresh from London I must slaughter. "Sze Tho. Yee leong tiew siang kai, moew tat teng!" (Sze Tho. These two chicks are quite a handful) Now Tau Boon is not one of those chaps one would describe as being too fond of exaggeration. A spade is a spade to this man and when he says he has nice chicks, he has nice chicks! From his description, he sounded like an orgy was possible, so I got hold of my other two frustrated friends, Seah Wan Tat and his cousin, Francis. I was scheduled to in January to marry, and I thought this could be the last summer before my winter of discontent. At the bar, Tau Boon handed me the hand of this young dashing lady. She was devilishly dressed low cut and looked delicious. "This is Olivia. Olivia, this is Casey." I shook hands with high expectations, but noted a familiar rascality in her eyes. The bushy wave of hair maybe missing, but the voice was unmistakable. "Sze Poh!" I shouted! " Sze Tho!" came the reply. How strange. In school you may be known as just plain Lim Tau Boon. After school you become ‘Edward’; Sze Tho, becomes ‘Casey’ and Sze Poh--‘Olivia’. Everyone was borrowing an English name for the future, as if we no longer wished for a Chinese past. We were dangerously becoming more Anglo and less Chinese. Sze Gnor, Sze Poh’s younger sister was also there. She was a gem of a find for the itchy Francis, a young provision shop owner, loaded with money and a gun cocked for action. He had dirt on his hands and wanted chicken for breakfast. I was disappointed I had bumped into an old friend who lived in the same street in Seremban, and who--probably, had the same type of toilet training I had, because she was puffing like a chimney! But the gang was determined to have a good time and settled down quickly. We started relishing and regaling old times. It was a heart-warming session, tickled with laughter. It was strange, however, as the laughter from Sze Poh grew louder each time she emerged from the powder room. It looked like the loo was a place for the infusion of her ‘happy’ hormones, because she was packing more laughs with every successive pee. We were having a great time, but the reunion was without alcohol since the bar was closed and we started late. Without some ‘magic juices’ the night looked incomplete. " Edward," I asked, "bring more beers." "Casey, the bar is closed." "Edward…heh, how about other drinks?" "Casey, the bar is closed." "Edward. How about we go out and buy some hard liquors and beers back? You ok with that?" "You want to die, huh. Get me fired? If my boss finds out, I’ll get fired!" "Edward. You the big man here, what lah. Get the key to the drink cabinet, maey kow tim loh." (Overlook our indulgence please?) "Casey. What key. You think this my father’s hotel, eh?" I would go on with this incessant pestering for hours on end at every opportunity I felt Edward could be convinced agreeable. But this Boy’s Brigade Captain would not budge an inch. No beers. No hard liquor. Only sky juice. In the company of two girls whose laughter grew louder and louder progressively they pee, the situation seemed ridiculously out of context! Then opportunity looked godsend. Once, just once when Tau Boon left the table to pee, Sze Poh whipped out the cause of her incurable laugher. On a round table under a dim light, she rolled up a stick of grass. Making sure none dropped off, she packed it tightly, sealed it with a whiff of her saliva the end, and lit the stick. She puffed deeply first, then passed it around. Soon the six of us were mad as hell! When Tau Boon returned, he was the last person in the circle, so we let him keep the stick. It was only half done, and it could still pack quite a few more puffs. Tau Boon drew a deep breath in. "This is good, Sze Poh. Maey yeah lay kah?" (What is this?) "Finish it. Don’t waste." she said. Then she lit up another, and another. Soon, Tau Boon was hanging to the little grass sticks like a squirrel hanging to nuts! When it was about time, I kicked her under the table. She leaned forward, threw the full force the weight of her chest against Tau Boon’s face and whispered, " Tau Boon darling, no drinks, huh?" I don’t know whether it was her big bosom that did the job or the grass, but Tau Boon was aroused and awakened! Without hesitation, Tau Boon dug into his pocket and rang a bunch of keys in her ear. "Who said no drinks?" he barked affectionally. "Tai pah, lah!" (Plenty). Tau Boon then staggered away and returned with beers, brandy, whiskeys and plenty of tit-bits to the boot. The incomprehensible, but now highly motivated assistant manager had raided the hotel’s inventory of heavy metal drinks, and was staggering back like a regular drunk! When we had polished off the bottles, Sze Poh made him stumbled back for more. She would press her body upon his nose, and he would respond clockwork like some zombie on fire! Then, once out of his line of sight, we would release our stomach muscles and roll on the floor, like rats swirling inside a whirlpool! Whenever he returned, we would upright our chest, compress our lungs and pretended that nothing was amiss. Tau Boon made several more trips that night, until the cupboard was nearly empty. By then, the six of us were already so pissed high, we needed help just standing up! The next day we called Tau Boon. He sounded ok, but didn’t remember much of the evening, so we asked him to check his bar cabinet. After some quick accounting, he called back with panic: " Tiew, Sze Tho. Ee pai saey leh. Olivia took saey gnor with her leong lup lean . Kum pai kunn chow yow yee!" (Screw. Sze Tho. Die lah. Olivia poisoned me with two nuts. This time, sure going to get fired!) ___________________________________________________________________________ Footnotes: *1. With my vocabulary improving by geometric leaps, I was soon in the company alongside other lovers of the language--Yeo Siang Boon, Ranjit Singh, Lai Cheng and Sze Poh. I am going to pay tribute to them for your memory. They were the towering English giants of my generation that came out of ACS in 1971. Siang Boon would devour the likes of Enid Blyton’s books from the town library like a termite bound for wood. She was also a hopeless romantic, a gift unusual for a doctor today. Her vocabulary used to be larger than my pocket-sized Collin Dictionary Book. She now resides in Texas, America. Ranjit Singh, on the other hand, had a secret obsession for all things English, especially British football magazines. In Form 3, he wrote in our class magazine the story of a one Mr. Ferguson, which I thought was a story with a unique brand of suave iconoclasm, and a delightful reminder of his rascality. My best friend in Form 5 went on to university to read Literature, married a Eurasian and till this day, has not resurfaced. Lai Cheng was born a genius, so English was effortless for someone so blessed. She has excelled in anything and everything, and to write her achievements would take up too much space, so I shall talk less of this mortal. She is married to Jonathan, a successful lawyer and they both live outside London. Lai Cheng trained as a general practitioner in England but now prefers the routine of a mother to two children. Sze Poh’s indulgence as a voracious reader in love novels made her quiet and pensive, and she remained many years an incurable romantic. She is today my newly discovered email pen pal. She lives with her family in Seremban and teaches English. She still smokes a little. She has not rolled ‘grass’ since the 1980 incident as Tau Boon tracked down the supplier and killed him. (Tau Boon left behind a few broken hearts and married an incredibly good-looking secretary with the heart of a princess. She is earthshaking beautiful and on his wedding day, many of us wept. He is now general manager of a major hotel chain in Guangzhou. Despite being the general manager, he is no longer allowed the bar keys) *2. Studying English became an obsession for another reason. Mrs. Yap Swi Neo, our literature teacher had virtually demanded I be expelled from her class because I was always eating during her lesson. My prefect schedule to ‘jaga’ the tuck shop was partly to be blamed for it meant I was always deprived breakfast if I were to make it to Literature class. I had gastric problems, so food was not a degree of choice. I didn’t have time to sit and eat and be back to class on time, so what food I could confiscate during duty, I brought to class to consume. Ranjit was aware of my problem too, and he tucked in food alongside me because he hated Mrs. Yap. Mrs. Yap saw me as a ‘recalcitrant wayward prefect’ and had me sent out of her class almost the entire year. I was deprived of proper instructions in English, so I took to grandma’s ‘modified sticks’ and studied English Literature in the loo instead. When I got an ‘A’ for her paper at year-end, it was revenge sweet (I should have included my Malay too in my loo reading but I didn’t, and got an ‘F’). But trouble was looming at another horizon. Meng Yin was class monitor and a Prefect. Peck Yen was also a Prefect, and the two sat near us at class. One of the two reported our intransigence to the Prefectory Board, to seeking our expulsion. The charge was eating in class. Period. Ranjit was spared, as he was Chairman of the Disciplinary Committee. I being only his assistant didn’t have clout, so I was earmarked for expulsion through a handvote. Those who wanted me cashiered as a Prefect, had to raise their hands. When the votes were tabulated, I survived by the narrowest of margin, so I kept my blazer and badge. I stopped eating in class then, but continued to shit and smoke. *3. Today, I have progressed to pipe and cigars, but Mrs. Sze Tho rations my supply and my indulgence is merely a reward given when I behave. In 1999, I underwent emergency surgery to my bottom at Pantai Hospital when I tore a muscle inside my bottom laughing to Lat jokes. I recovered, but could not sit on anything else but a rubber tube for two weeks, so I sat sideways and completed The Story of Singapore by Lee Kwan Yew. Now, I do all my reading sideways. I no longer read and smoke in the toilet since the incident but I have learnt it is possible to eat and shit at the same time and I am doing more practice. Casey Sze Tho