DOC (authorversion)

advertisement

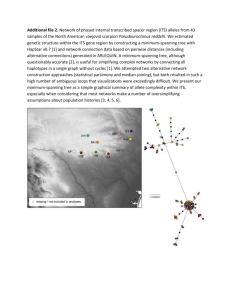

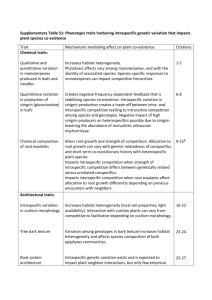

1 Idiosyncrasy in ecology – What’s in a word? 2 WHG Hol1*, KM Meyer2, WH van der Putten1,3 3 4 1 5 Wageningen, The Netherlands 6 2 7 Büsgenweg 4, 37077 Göttingen, Germany 8 3 9 Netherlands Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW), Droevendaalsesteeg 10, 6708 PB Göttingen University, Faculty of Forest Sciences and Forest Ecology, Ecosystem Modelling, Wageningen University, Laboratory of Nematology, P.O. Box 8123, 6700 ES Wageningen, The 10 11 12 * 13 Netherlands Institute of Ecology, Droevendaalsesteeg 10, 6708 PB Wageningen, The 14 Netherlands. Email: g.hol@nioo.knaw.nl 15 Phone: +31 317473610, Fax: +31 317473675 Corresponding author: WHG (Gera) Hol 16 17 18 Running headline: Idiosyncrasy in ecology 19 Ecological research aims at finding general rules and principles, but the variation in nature is 20 seemingly endless. General ecological rules are rare and they apply best to large-scale patterns 21 (Lawton 1999). At small to intermediate scales, effects can depend on species identity or 22 environment and are often called ‘idiosyncratic’. We noticed that idiosyncrasy is becoming used 23 more frequently in ecological papers. This observation triggered a literature study of the word 24 idiosyncrasy to answer the following questions: Is idiosyncrasy in ecology a new trend? What is 25 idiosyncrasy used for? In which journals do we find idiosyncrasy? Should we welcome a further 26 increase of the use of idiosyncrasy in ecology? 27 We used Web of Science® to search for papers in ecological journals containing the 28 word “idiosyncrasy” or “idiosyncratic” in title, summary or keywords. The idiosyn* papers in 29 ecological journals increased from 4 (average 1991-1996) to 21 (average 2005-2010) per year. 30 The same increase is also visible when looking at the proportion of idiosyn* papers in ecological 31 journals (Fig. 1), showing that the increase in idiosyncrasy papers is not just due to an increase in 32 the total number of ecological papers per year. The correlation between year and proportion 33 idiosyn* papers is significant (Spearman rank correlation rs = 0.81, P < 0.001) and the best fit is 34 an exponential curve, growing by 7% per year. This confirmed our personal observation: 35 idiosyncrasy in ecology is a new trend. 36 What is then idiosyncrasy? According to the Oxford Dictionary, idiosyncrasy is 37 something peculiar to an individual, e.g. a feeling, view or mode of expression. It can also be 38 used for a distinctive characteristic of something and in medicine it is used for individuals with 39 an allergic reaction. We screened all idiosyn* papers in ecological journals up to date to find out 40 what idiosyncrasy was used for exactly. The first ecological paper using idiosyncrasy also 41 applied it at the level of individuals, i.e. chemical variation in individual grasshoppers (Jones 42 1986). In the other idiosyn* papers in ecology it has been used for aggregation levels from 43 individuals, species, families, functional groups and ecosystems up to landscapes, but the species 44 levels is most common. The phenomena that were described can be grouped arbitrarily into three 45 common forms of idiosyn* usage: scatter, interactions and outliers. Scatter includes positive, 46 negative and neutral effects of individuals or species to a treatment or environment (e.g. 47 Boecklen et al. 1991). Non-additive or nonlinear relationships (Brinkman et al. 2005; Hoorens et 48 al. 2010) between treatment and response are often reported as idiosyncratic effects. Consistent 49 deviations from the norm, which are visible as outliers in plots of experimental data, indicate 50 unique behaviour of individual species and are also labelled as idiosyncratic effects (Kappeler 51 1997; Edwards et al. 2001). We realize that one word can have multiple meanings and 52 sometimes the intended meaning can be deducted from the context. However, the use of 53 idiosyncrasy may result in confusion or even contradiction. For most authors idiosyncrasy seems 54 to be a synonym of “unpredictable” or “lack of patterns”, while others argue that idiosyncrasies 55 can be predictable (Emmerson et al. 2001). Quite a few papers use idiosyn* as an alternative for 56 species-specific; yet we also found the notion “species-specific and somewhat idiosyncratic”, 57 suggesting that the two terms are not the same. Unfortunately, 25% of the papers use 58 idiosyncrasy in the abstract only which makes it nearly impossible to pinpoint what kind of 59 idiosyncrasy the authors refer to. 60 In Web of Science® we found 74 source titles (mostly journals) for the 220 ecological 61 papers containing idiosyn*. The list is headed by Oikos, followed by Ecology, Global Ecology 62 and Biogeography, Evolution and Oecologia. This raised the question whether high impact 63 journals are more likely to publish idiosyn* papers than lower impact journals, which is indeed 64 the case (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). It will be difficult to determine whether high impact 65 journals have different vocabulary or whether this positive relation between impact and 66 idiosyncrasy is due to the difference in topics between journals. Many papers appear to have no 67 links with other idiosyn* papers via shared authors or via citation and this shows idiosyncrasy as 68 a widespread, but disconnected label (Fig. 2). The lack of context and definition severely 69 hampers interpretation. There are a few clusters with five or more papers (Fig. 2) and within the 70 contexts of those clusters it might be clearer what is meant by “idiosyncrasy”. The two largest 71 clusters are in the area of biodiversity-ecosystem functioning and biogeography. 72 We conclude that currently idiosyncrasy is not a very meaningful label, given the non- 73 defined use and difficulties to deduct which of the many meanings is referred to by the authors. 74 The obvious solution is, when ecologists can not agree on a common definition for idiosyncrasy, 75 to define it when used, or to replace idiosyncrasy by less ambiguous terms. Scientific writing 76 should match the accuracy of data collection and analysis. 77 78 79 80 81 Acknowledgements 82 W.H. is supported by the EU FP7 project SOILSERVICE. This is publication XXXX of the 83 84 85 86 87 NIOO-KNAW. 88 References 89 Atmar W and Patterson BD. 1993. The measure of order and disorder in the distribution of 90 91 92 93 species in fragmented habitat. Oecologia 96: 373-382. Boecklen WJ, Mopper S and Price PW. 1991. Size and shape-analysis of mineral resources in arroyo willow and their relation to sawfly densities. Ecol Res 6: 317-331. Brinkman EP, Duyts H and van der Putten WH. 2005. Consequences of variation in species 94 diversity in a community of root-feeding herbivores for nematode dynamics and host 95 plant biomass. Oikos 110: 417-427. 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 Edwards W, Gadek P, Weber E. et al. 2001. Idiosyncratic phenomenon of regeneration from cotyledons in the idiot fruit tree, Idiospermum australiense. Austral Ecol 26: 254-258. Emmerson MC, Solan M, Ernes C. et al. 2001. Consistent patterns and the idiosyncratic effects of biodiversity in marine ecosystems. Nature 411: 73-77. Jones CG, Hess TA, Whitman DW, et al. 1986. Idiosyncratic variation in chemical defenses among individual generalist grasshoppers. J Chem Ecol 12: 749-761. Kappeler PM. 1997. Intrasexual selection in Mirza coquereli: evidence for scramble competition polygyny in a solitary primate. Behavior Ecol Sociobiol 41: 115-127. 104 Lawton JH. 1999. Are there general laws in ecology? Oikos 84: 177-192. 105 Thomson Reuters. 2010. ISI Web of Knowledge, Philadelphia. 106 107 108 109 Figure legends 110 111 Figure 1. Proportion of papers using idiosyn* in ecological journals between 1991-2010; based 112 on ISI Web of Knowledge (Thomson Reuters 2010), Topic: idiosyn*, Years: 1991-2010, Subject 113 area: ecology). 114 115 Figure 2. Network showing links between idiosyn* papers in ecological journals 1986-2011. 116 Each dot represents a paper (n=216) and papers can be linked via authors or via citations. Single 117 arrows indicate a citation; double arrows indicate papers that share at least one author and these 118 can also be linked via citation. 119 120 121 122 Fig 1 123 124 125 Fig 2 126 Supplementary Material 127 128 129 Figure S1. The relation between the 5 Year Impact Factor of a journal and the number of 130 observed – expected idiosyn* papers per journal. Numbers refer to journal titles, listed at the end 131 of the section below. 132 To correct for the number of publications per journal, we calculated the expected number of 133 idiosyn* papers as if they were occurring at random throughout all ecological journals. Journals 134 publishing more papers would thus be more likely to have more idiosyn* papers. 135 With help of Web of Science® the total number of publications in ecological journals was 136 calculated between 1986-2010. A total of 149 ecological journals were selected based on the 137 subject category Ecology in the Journal Citation Reports®. Together these journals published 138 241310 papers between 1986-2010. In this period 213 idiosyn* papers were published in 139 ecological journals (Topic = idiosyn*; Subject area = ecology). The observed idiosyn* papers 140 per journal was obtained using the Analyze Results option based on Source Title. The expected 141 number of idiosyn* papers per journal was calculated as follows: (total number of idiosyn* 142 papers/total number of ecological publications) x total number of publications per journal. The 143 difference between observed and expected idiosyn* papers per journal was plotted against the 5- 144 Year Impact Factor 2009. We preferred the 5-Year Impact Factor over the yearly impact factor 145 as a more robust measure of impact. Since not all 149 journals had a 5-Year Impact Factor 2009, 146 only 124 points are plotted in the figure. Each number refers to a journal. 1: Trends Ecol Evol, 2: 147 Annu Rev Ecol Evol S, 3: Ecol Lett, 4: Ecol Monogr, 5: B Am Mus Nat Hist, 6: Global Change 148 Biol, 7: Front Ecol Environ, 8: ISME J, 9: Mol Ecol, 10: Global Ecol Biogeogr, 11: Ecology, 12: 149 Evolution, 13: J Ecol, 14: J Appl Ecol, 15: Am Nat, 16: Perspect Plant Ecol, 17: Conserv Biol, 150 18: P Roy Soc B-Biol Sci, 19: Ecography, 20: Ecol Appl, 21: J Biogeogr, 22: J Anim Ecol, 23: 151 Ecosystems, 24: Divers Distrib, 25: Heredity, 26: Funct Ecol, 27: J Evolution Biol, 28: 152 Oecologia, 29: Oikos, 30: Biol Conserv, 31: Biol Letters, 32: Biogeosciences, 33: Wildlife 153 Monogr, 34: Biol Invasions, 35: Landscape Ecol, 36: Paleobiology, 37: Agr Ecosyst Environ, 38: 154 Behav Ecol, 39: Microb Ecol, 40: Ecol Eng, 41: Behav Ecol Sociobiol, 42: J N Am Benthol Soc, 10 155 43: Ecol Soc, 44: Mar Ecol – Prog Ser, 45: Evol Ecol, 46: J Veg Sci, 47: Basic Appl Ecol, 48: 156 Ecotoxicology, 49: Landscape Urban Plan, 50: Ecol Econ, 51: Adv Ecol Res, 52: J Chem Ecol, 157 53: Aquat Microb Ecol, 54: Mol Ecol Notes, 55: Anim Conserv, 56: Restor Ecol, 57: Ecol 158 Complex, 58: J Exp Mar Biol Ecol, 59: Ecol Model, 60: Biotropica, 61: Biodivers Conserv, 62: 159 Plant Ecol, 63: Theor Popul Biol, 64: Chemoecol, 65: Austral Ecol, 66: J Arid Environ, 67: 160 Pedobiologia, 68: Popul Ecol, 69: Ecol Ecol Res, 70: Acta Oecol, 71: Appl Veg Sci, 72: 161 Wetlands, 73: J Wildlife Manage, 74: J Trop Ecol, 75: Ecohyddrology, 76: Polar Biol, 77: 162 Ecoscience, 78: Oryx, 79: Ecol Res, 80: Aquat Ecol, 81: Ann Zool Fenn, 82: Eur J Soil Biol, 83: 163 Ecol Inform, 84: Environ Biol Fish, 85: Theor Ecol-Neth, 86: J Soil Water Conserv, 87: Polar 164 Res, 88: Eur J Wildlife Res, 89: Mol Ecol Resour, 90: Wildlife Res, 91: Biochem Syst Ecol, 92: 165 Compost Sci Util, 93: Mar Biol Res, 94: Wildlife Biol, 95: Rangeland Ecol Manag, 96: Rev Chil 166 Hist Nat, 97: New Zeal J Ecol, 98: Rangeland J, 99: Am Midl Nat, 100: Afr J Ecol, 101: Fungal 167 Eco, 102: Nat Area J, 103: S Afr J Wildl Res, 104: Vie Milieu, 105: Community Ecol, 106: J Nat 168 Hist, 107: Int J Sust Dev World, 108: P Acad Nat Sci Phila, 109: Pol J Ecol, 110: Southeast Nat, 169 111: Polar Rec, 112: Northeast Nat, 113: Northwest Sci, 114: J Freshwater Ecol, 115: Russ J 170 Ecol+, 116: Southwest Nat, 117: West N Am Naturalist, 118: Interciencia, 119: Amazoniana, 171 120: Rev Ecol – Terre Vie, 121: Can Field Nat, 122: Ohio J Sci, 123: Contemp Probl Ecol, 124: 172 Nat Hist. 173 174 11