MS-Word - Natural Resources Institute

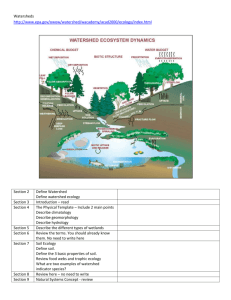

advertisement