Translation Theory (Spring 2006)

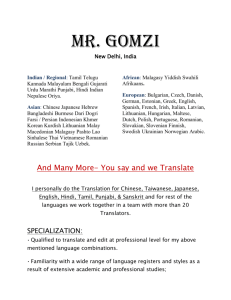

advertisement

1 Roda P. Roberts (1992) The Concept of Function of Translation and Its Application to Literary Texts Target 14-1 (1992), 1-16 Abstract: Many translation theorists have adopted a functional approach to translation in an attempt to guide and explain the difficult choices a translator must make. This paper argues that it is the function of the translation; and not the functions of language or the function of the source text, that is the translator’s guiding force. Having defined the function of translation as the application or use when the translation is intended to have in the context of the target situation, various functions that a literary translation may serve are examined. Finally, using the criteria of functions of language, functions of (source) text and functions of translation, an attempt is made to show that the type and degree of coincidence between the formal manifestations of the functions of language in the source text, the function of the source text and the translation depend on the precise function of the latter. Introduction The dilemma of the translation of literary texts, brought out by many translation theorists over the centuries, has been expressed in the following words by Pavel Toper: As a cultural phenomenon, genuinely creative translation is, in its essence, dialectally contradictory by virtue of the fact that it must produce a work of national literature out of a work, belonging to another language, while at the same time retaining those qualities that made it a work of art for its mother nation of that language.(Toper 1978: 44) The dilemma, as expressed by Toper, is based on two suppositions: (a) that the translation of a literary text must itself become a work of national literature; and (b) that it must retain the same qualities as the original. Both these suppositions will be reexamined from a functional point of view in this paper. The attempt to guide and explain the difficult choices a translator (particularly a translator of literary texts) must make on the basis of functions is by no means new. Translation theorists such as Nida, Newmark, Reiβ and Vermeer have adopted such an approach, but with relatively limited success. There seem to be two main reasons for this lack of success. First, they have equated functions of language with functions of texts. Second, they have not made a clear demarcation between the function of the source text and that of the translation. In this paper, I will begin by making a distinction between these three different types of functions. Next, I will examine the various functions that translations of literary texts may serve. Finally, I will attempt to show that the type and degree of coincidence between the source text and the translation depend on the precise function of the translation, rather than on the function of the source text. Language, Text and Functions Translation, being both an interlingual and an intertextual phenomenon, involves both the functions of language and the functions of text. Moreover, since the process of translation involves two different texts, the source text and the target text, the functions of the latter must be further distinguished from those of the former. Since, without language, there would be no text, whether source or target, any theoretical discussion of translation must necessarily begin with a discussion of language and its functions. 1.1. Functions of Language Language is regarded here as social behaviour, the means whereby people interact in different contexts of situation. Language is as it is because of what it has to do. The link between language and social behaviour is evident in the case of children: a child knows what language is because he knows what language does; language is defined for the child by its uses; learning one’s language is learning the uses of language, its "functions", and the meaning potential associated with them. While the uses of language in the case of a child are relatively limited, with each use or function being associated with some meaning potential and a minimal 2 structure for purposes of expressing if, the adult language is characterized by diversity of use, with a speaker using language in any given utterance for a variety of purposes. Thus, one cannot equate each instance of adult language use with a specific language function. But one can nevertheless identify a certain number of what Halliday has termed "macro-functions", which are "the highly abstract linguistic reflexes of the multiplicity of social uses of language" (Halliday 1973: 36), only indirectly related to specific uses of language but nevertheless recognizable as abstract representations of the basic functions which language is made to serve. These generalized functions of language define the total meaning potential of the adult language system. This meaning potential is the linguistic realization of the behaviour potential. The meaning potential is in turn realized in the language system as lexico-grammatical potential. Each stage can be expressed in the form of options: the options in the construction of linguistic forms serve to realize options in meaning, which in turn realize options in behaviour which are interpretable in’ terms of a social theory (Halliday 1973: 51-52).’ , Halliday has identified two extrinsic macro-functions: the ideational and the interpersonal. The ideational function, which covers language as reflection, represents the speaker’s meaning potential as an observer. It is the content function of language. It corresponds very closely to Karl Bühler’s representational function and Peter Newmark’s informative function, except that it introduces the further distinction within it of experiential and logical functions. The interpersonal function, which enables language to become action; represents the speaker’s meaning potential as an intruder. This is the component through which the speaker intrudes himself into the context of situation, both expressing his own attitudes and judgements and seeking to influence the attitudes and behaviour of others. Halliday’s interpersonal function corresponds more or less to the sum of Bühler’s conative and expressive functions and Newmark’s vocative and expressive functions. Halliday does not distinguish between the latter, since he feels that in the linguistic system the two are not distinguishable. Halliday’s two extrinsic macro-functions are realized through structures of the lexicogrammatical system in texts, which are semantic units whose creation is made possible by a third macro-function he has identified, one intrinsic to language, the textual function.1 The textual component represents the speaker’s text-forming potential: it expresses the relation of the language to its environment, including both the verbal environment and the situation al environment. Every text manifests both the ideational and the interpersonal funclions of language. This is clearly seen by the following analysis of one simple sentence by Halliday (1973: 43):2 This gazebo was built by Sir Christopher Wren.2 The ideational function, which is represented by transitivity (the way different types of process of the external world are interpreted and expressed in language), is manifested here through the presentation of a material (action/creation) process in the structure Goal: thing effected (this gazebo) - Process: material/action (was built) - Actor: Agent: animate (by Sir Christopher Wren). The interpersonal function, which is represented by mood (the selection by the speaker of a particular role in the speech situation and his determination of the choice of roles for the addressee) and modality (the expression of the speaker’ s judgements and predictions), is manifested here in the indicative, non-modalized form by the structural elements Subject (this gazebo) - Predicator (was built) - Adjunct (by Sir Christopher Wren). While the example analyzed above is that of a sentence and a text is not a supersentence but a semantic unit encoded in sentences, it nevertheless becomes clear that it is an oversimplification, if not an error, to equate language functions with text functions and to base text types on specific language functions, as Peter Newmark does (1981: 12-16). Using Bühler’s three language functions as a starting point, Newmark identifies three text types: the informative (content-oriented), the expressive (author-oriented), and the vocative (readeroriented). He then goes further and categorizes representative examples of each text type. And, in so doing, he classifies most literary texts (serious imaginative literature, autobiography, 3 essays, and personal correspondence) as expressive text types, placing only what he calls ‘popular fiction’: ("whose purpose is to sell the book/entertain the reader") in the vocative text category. However, such a classification further illustrates the fallacy of equating functions of language and functions of text. Take, for instance, the case of Emile Zola’s novels. Using Newmark’s arguments, they would be categorized a priori as texts with an expressive function, since they are considered "serious imaginative literature". However, while there is no doubt that the expressive function is evident therein, there is also little doubt that the informative function plays an important role through numerous, precise descriptions of a documentary nature, which Zola uses to present the social backdrop against which his characters evolve. This double function is clearly indicated in the preface to the novel L’Assommoir (1923, Vol. 1: v): "J’ai voulu peindre la déchéance fatale d’une famille ouvrière, dans le milieu empesté de nos faubourgs". Hence, the detailed presentation in this novel of one small, clearly circumscribed district of Paris, the district immediately northwest of the Gare du Nord. This merging of the informative and expressive functions of language in L’Assommoir and other novels and stories by Zola and his fellow novelists is explained by Zola in Le Roman expérimental, where be describes the dual role of the naturalist novelist: he is an observer who presents facts as they are, while at the same time he is an experimenter who moves his characters around in a particular plot. Thus, he himself sees the informative function as no less important in his novels than the expressive function. To sum up, then, using Juliane House’s words (1977: 36), given that language has functions a to n, and that any text is a self-contained instance of language, it should follow that a text also exhibits functions a to n, and not, as is presupposed by those who set up functional text typologies, that any text will exhibit one of the functions a to n.3 . 1.2. Function of a Text If the function of an individual text does not correspond to one function of language, what is it and how can it be established? I adopt here House’s definition of the function of a text as "the application … or use which the text has in the particular context of a situation" (House 1977: 37).4 This definition reflects very appropriately Halliday’s basic idea that a text is embedded in a context of situation. The context of situation of any text is an instance of a generalized social context or situation type, which is a semiotic structure. The semiotic structure of the situation is formed out of sociosemiotic variables, i.e. situational dimensions. While Halliday lists three primary ones - field (type of activity in which the text has significant function), tenor (status and role relationships involved) and mode (medium, rhetorical mode, etc.) - House adapts Crystal and Davy’s (1969) more elaborate system of situational dimensions for the purpose of establishing a text’s function (House 1977: 37-50). Her basic postulate is that the situational dimensions and their text-specific linguistic correlates are the means whereby a text’s function is realized; therefore, the function of a text can be determined by analyzing the text along certain situation al dimensions. The function of a text, established according to House’s model, while not corresponding to any one function of language, is by no means completely divorced from language functions. First, as Halliday has shown (1978: 123), there is a systematic relation between certain situational dimensions and functions of language: field and the ideational function; tenor and the interpersonal function. Second, the text function is stated by House in terms of Halliday’s two extrinsic macro-functions, the ideational and the interpersonal, which are found in all texts. Thus, for instance, her analysis of a comedy dialogue from Sean O’Casey’s "The End of the Beginning", conducted, in terms of situational dimensions and their linguistic manifestations (House 1977: 169-184), leads to the following summary statement of the function of the text: The function of the written text which consists of an ideational and an interpersonal component may be summed up in the following way: it is to enable the reader to 4 reconstruct a piece of simulated reality depicting an everyday, very intimate domestic quarrel for his entertainment and his pleasure. The text’s ideational functional component is not marked on any of the situational dimensions; nevertheless, it is implicitly present in that the text, of course, informs the addressees about certain events taking place between two particular persons. However, the ideational component is clearly less important than the interpersonal one which is marked on two dimensions of the language user [geographical origin and social class] and, on all five dimensions of language use [medium, participation, social role relationship, social attitude, and province]. (House 1977: 179) If House’s definition of the function of a text and her method of establishing it provide a promising avenue for theoretical research,5 her idea of the function of a translation seems stereotypical, at least at the start. She begins by stating, as do Newmark, Nida and many others, that the function of a translation must be equivalent to that of the source text (House 1977: 30). Although she does temper this statement after the analysis of eight texts (only some of which are literary) and their translations, her conclusion remains limited and unsatisfactory. According to her, there are two main translation types: covert translation, in which the function of the ST is found intact in the translation, and overt translation, in which there is no direct match between the function of the ST and the function of the translation (House 1977: 204207). However, she continues to consider the function of a translation in light of the function of the ST. What seems to be required is an independent consideration of the functions of translation. 2. Functions of Translation The justification for considering the functions of translation independently of the functions of source texts lies in the fact that the reasons for translation are independent of the reasons for the creation of any source text. The function of a translation can thus be defined as "the application or use which the translation is intended to have in the context of the target situation".6 The functions of translation - and thus the form and type of the translation - can vary considerably on the basis of several factors: among them are the status that a translation is to have in the target society and the initiator of the translation. The status of a translation is determined by its relationship to the source text. One can distinguish - as does J.C. Sager (1983: 122-123) between three basic statuses that a translation can have. First, there is type A: the translation that is an independent document, a full substitute for the monolingual reader. It may have the same function as the original or be a derived text serving a different function. Second, there is type B: a translation that is an alternative to the original and coexists with it. It too may reflect the function of the original or serve a different function. Finally, there is type C: the translation that is a full equal to the original in all respects, including function, and may therefore serve as a basis for other translations. Those who speak of the great difficulties of literary translation, if not of its impossibility, regard this third status as the only one worth striving for in the translation of literary texts, ignoring the fact that other statuses may be equally valid in given circumstances. The role of the initiator of a translation can also affect the function of translation. If the initiator is the publisher of the original work, who commissions a translation to open up another language market, then the translation normally has status type A presented above, with a function similar to that of the source text. The same is normally true of the translation initiated by the original writer. The translator, as initiator, may also aim at a type A translation, but not necessarily with the same function as the original. On the other hand; if the initiator is a reader group or its representative, the translation will often be of type B. The reader knows that there is an original which he wants to read but is unable to do so without a translation. Many university literature professors, acting as reader representatives, serve as initiators (and sometimes as producers) of such translations, for they realize that their students do not have the necessary language skills to understand much foreign literature. Finally, the type C status is 5 the oft-unfulfilled dream of many literary translators who initiate translation with the goal of producing a full equal of the original text. 2.1. Functions of Translations of Literary Texts Taking into consideration the above factors, one can begin to identify the various functions that translations of literary texts may have, i.e. the applications or uses which they are intended to have in the context of the target situation. The following list, which does not claim to be exhaustive, gives a number of applications which may affect the nature of the translation: - presentation of thematic content - presentation of writer’s point of view and style - introduction of different cultural elements into the target society - introduction of new literary forms into the target literature - introduction of new linguistic forms into the target language, - helping the reader penetrate the original text through its translation - creating a work that becomes part of the target literature. These functions are not necessarily mutually exclusive and therefore several may apply to the same translation. Since each of them has implications for translation strategy, they will be individually examined below. 1. Presentation of thematic content is the dominant function of most translations of popular literature. Let us take, as an example, the booming business of Harlequin novels, romantic novels written in English whose popularity is based primarily on their romantic plots. Their translation into French, which seems to be an equally thriving business, involves little more than the presentation of thematic content. 2. Presentation of the writer’s point of view and style has been the reason for many translations of literary texts. For example, the famous French writer André Gide chose to translate Rabindranath Tagore’s poetry precisely because he empathised with his views, feelings and approach, and wanted to familiarize the French public with them.7 3. Introduction of TL readers to new cultural elements is, obviously, a feature of most translations of literature; in fact, it seems to be the primary function of the translation of many African and Asian works today. Translations with this function are often preceded by an introduction to the cultural background of the text and accompanied by footnotes that explain cultural allusions in the text. Translations of the works of the Cameroonian writer Ferdinand Oyono, published in the African Writers Series by Heinemann, are good examples of this particular function. 4. Introduction of new literary forms into the target literature through translation is well recorded in literary history. For instance, Latin epic poetry was initiated in the 3rd century BC by Livius Andronicus; who translated Homer’s Odyssey into the traditional metre of Saturnian verse. And Virgil’s unfinished Aeneid, considered the first truly Latin epic, is nevertheless patterned after the Odyssey, with many imitative passages and even direct translations. 5. The introduction of new linguistic forms into the target language is constantly effected by translations of all kinds, which often contain loanwords and loan-translations. While it is relatively rare for linguistic innovation to be consciously made their primary function, a few translations are remembered primarily for their contribution to the development of the target language. Thus, Martin Luther’s translation’ of the Bible into German in 1534 is regarded as 6 having been a main influence in establishing Modern High German as the literary standard for the unified Germany of a later century. 6. While all translations are intended to help readers overcome the language barrier, some have as their specific function the penetration of the source text by means of the translation. In other words, the translation serves as a gloss to the original for readers who have little or no knowledge of the source language. Translations found in the Penguin books of verse typify this function. As the General Editor’s Foreword to The Penguin Book of French Verse 4 clearly states: The purpose of these Penguin books of verse in the chief European languages is to make a fair selection of the world’s finest poetry available to readers who could not, but for the translations at the foot of each page, approach it without dictionaries and a slow plodding from line to line. . . if they are willing to start with a careful word for word comparison, they will soon dispense with the English, and read a poem by Petrarch, Campanella, or Montale … straight through. (Harley 1959: v) To fulfill this function, the translations are literal, although grammatically correct, prose translations, intended to guide the reader in his reading of the original. 7. While the function of such translations is to constantly draw the reader’s attention to the original, that of many others is to make the translation an integral part of the target literary polysystem. In other words, the primary function of the translation is to become acceptable in terms of the norms of the target system. Thus, the 17th century translations in France that have been dubbed the "belles infidèles" can be explained by the fact that in that period of "préciosité", stylistic adornments and gallant behaviour were not only popular but expected by the French readership and were thus introduced into translations, even if this involved distortion of the source text. 2.2. Functional Analysis of Four Translations of Thomas De Quincey’s “Confessions of an English Opium-Eater” The above presentation of different potential functions of translation can be illustrated and complemented by an analysis of a number of translations of one given literary text, each having its own distinct dominant function. This will be done here using four different French translations of Thomas De Quincey’s Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, first published in two parts in the London Magazine of September and October 1821, with a revised and much longer version published in 1856.8 This work has attracted much attention in France, where its first translation appeared in 1828 and where it is still being retranslated in the second half of the twentieth century. The first translation (1828), published under the tide L’Anglais mangeur d’opium, was commissioned by the publisher M. Mame and carried out by Alfred de Musset, well before he became famous as a writer in his own right. A comparison of this translation with the original reveals several sections in which the translator takes liberties with the original. His intention to "francicize" the text is clearly revealed by the fact that he wanted the translation to be entitled simply Le mangeur d’opium. While this was not allowed by the publisher, the translation is nevertheless Musset’s appropriation and adaptation of the Confessions. In some passages, he merely abridges the original. In others, he "completes" the Confessions with additions that reflect the literary mode of the times: he interjects a dream about Spain, for instance, Spain being very fashionable in France during that period. Musset also modifies the tone and content of the famous invocation to opium, which is no longer the prayer that De Quincey intended it to be but a pretext for poetry. Both the point of view and the style are completely changed in that address. It is clear that De Quincey’s text is merely a starting point on which Musset has built his own text on the basis of his personal inclinations as well as those of his era. Musset’s translation-adaptation respects the language, customs and ideas of early 19th century France, rather than those of England at the same period. However, its poetic charm has allowed it to 7 survive the passage of time: not only is it included in the 1960 Gallimard edition of Musset’s (Euvres completes en prose, but it was republished in 1965 in a popular collection "Poche-Club", intended for the general public. A second translation of the Confessions, again by a famous poet’ - Baudelaire - appeared in 1860, in two parts, under the title Les Paradis artificiels. Baudelaire’s translation is also a partial one, although this was not by his desire: he undertook a full translation only to have it refused by publishers, who insisted on abridgement. So he was obliged to settle for a summary translation and was not at all sure of the success of the enterprise. But literary critics have no doubts about the important position occupied by this summary translation in the French literary polysystem: according to Claude Pichois (1964), Les Paradis artificiels, just like the Spleen de Paris, is an extraordinary poem in prose; and François Porché (1944) considers it a truly French work that makes De Quincey a part of French literature, and of French dreams. How did Baudelaire manage this feat while being obliged to summarize the original text? As Baudelaire himself indicated in a letter (1973: 668-669), De Quincey’s style was conversational and full of digressions. It was thus easy for him to eliminate the author’s asides, reflections and digressions without affecting what be considered to be the essence of the work. But Baudelaire’s aim was not to transform De Quincey’s Confessions, but rather to communicate his admiration for the author. And it was with great regret that he eliminated parts which were not directly related to the theme of opium. What he retains he translates with great attention to the structure of De Quincey’s impassioned prose, and with great care to find "les mots justes". He follows the original writer’s chain of thought step by step and respects his rhythm and his overall structure, using a literal approach while still creating a literary masterpiece. He became so much one with De Quincey that images from the latter were later incorporated into his own poetry. The next two translations of the Confessions - V. Descreux’s (1898) and Henry Borjane’s (1929) - both seem to have fallen rapidly into oblivion. They were replaced in the 1960’s by those of Pierre Leyris (1962) and Françoise Moreux (1964). Pierre Leyris’s Confessions d’un opiomane anglais, suivies de Suspiria de Profundis et de la Malle-poste anglaise, published by Gallimard in the NRF series, is intended for the reading pleasure of the general public. Although it is preceded by a translator’s preface in which the three De Quineey texts are presented, there are few scholarly remarks or footnotes. The reader is left to enjoy the text on his own. In the translation itself, Leyris attempts to follow the example set by Baudelaire, even integrating into his own translation passages translated by Baudelaire. However, the parts he himself has translated do not match Baudelaire’s style, nor that of De Quincey. The translation oscillates between the archaic and the modern, which disorients readers. Thus it does not really fulfill its function of providing the general public with the pleasure that De Quincey still provides in the original. Françoise Moreux’s translation was published along: with a 67-page introduction and 16 pages of notes in the "Colleetion bilingue des classiques étrangers", a collection intended primarily for students and, professors. As a professor of literature, who had written a thesis on De Quincey, Moreux was obviously interested in making the Confessions accessible to university students who do not know English very well. This function dominates both the nature of the translation and its presentation (introduction, notes, translation alongside the original). Moreux’s translation, while not as elegant as those of Baudelaire and Musset, fulfills perfectly adequately its function of allowing French readers to penetrate the original text. It focusses attention on the message of the original, in both form and content, without itself being a great work of art. This analysis of different translations of the same literary text has allowed us to see actualizations of different functions of translation, which I have described as the applications or uses translations are intended to have in a given context of situation. However, despite the fact that the various translations discussed above are all translations of the same literary text, not all of them would be considered by Gideon Toury to be literary translations. For, according to Toury’s definition, "literary translation" (as opposed to "literary" translation, which refers to 8 any translation of a literary text) implies not one, but two criteria: the first is that the translation be that of a literary text; the second, that the translation enter the target literary system (1980: 37; cf. also Toury 1984 and 1989). In other words, Toury’s approach implies that the function of literary translation is to create a work that can be integrated into the target literary polysystem. On the basis of this criterion, one could certainly consider Musset’s and Baudelaire’s Confessions as literary translations, but there would be some doubt about classifying Leyris’s and Moreux’s works in the same way. But how can one judge the position of a translation within the target literary system? The answer is not clearcut. For this reason, it seems preferable to consider translations of all literary texts as legitimate target texts "legitimate", that is, each in its own right - and to make distinctions between them according to their respective functions, as I have done above. Conclusion The starting point of this discussion was Newmark’s premise that a given function of language constitutes the function of a text, and House’s premise that the function of the source text should be reproduced in its translation. In other words, function of language = function of text = function of translation. What I have tried to show in this paper is that functions of language, of source text and of translation are not identical. In so doing, I have dispelled another commonly held belief that the type and degree of equivalence between the source text and translation depends on the function of language that dominates in the former or, more generally, on the function of the former. Newmark has postulated that in the translation of an expressive function text (i.e. literary text), the emphasis is on the source text or writer, the method used is "literal" ("semantic"), the unit of translation is small (ranging from the word to the collocation), and the length of the translation in relation to the original is approximately the same. But the above study of the De Quincey translations, however summary, clearly shows that the type and degree of equivalence cannot be predicted in terms of the source text function. It is the function of the translation that determines what will be omitted or added to it, whether it will closely follow the structure of the source text or will create a new structure of its own. It is the function of the translation that will determine whether those qualities of the source text that make it a work of art in the source literary polysystem would be retained in the translation. In many cases, the function of the source text cannot be recreated integrally if the function of the translation is to create a work that will be accepted into the target literature. In other words, acceptability of the translation in the target literature may well clash with adequacy of the translation in terms of fully reproducing the function of the source text. The position of literary translations - and, indeed, of all translations between the two poles of adequacy and acceptability identified by Toury (1980: 75) is ultimately determined by their function, which influences the type and degree of coincidence desirable or required between the source text and the translation. The establishment of this function is the translator’s most important decision, for it will have repercussions on his entire approach to the translation. In determining this function, he must take into consideration the function of the source text, on the one hand, and the context of situation in which the translation must function, on the other. Once the function of the translation is chosen, the many choices he has to make during the actual process of translating will be guided by this function, which becomes a beacon to the translator adrift on the perilous seas of translation. Notes 1. Halliday’s textual function must not be confused with the function of a text, which is discussed later in this paper. Halliday’s textual function is an intrinsic function of language, which makes it possible to use language to create text - any text. The function of a text, on the other hand, is particular to a given text. . 2. Halliday’s textual function is not analyzed here, since only his ideational and interpersonal functions 9 are comparable to the notion of function used in other approaches (e.g. Bühler, Jakobson) as a basic mode of language in use. 3. Roman Jakobson (1960), who has elaborated on Bühler’s functions, affirms that more than one function of language can be present in a text, with one being more dominant than the others. 4. House uses "application" in the technical sense attributed to it by John Lyons (1968: 434): "When items of different languages can be put into correspondence with one another on the basis of the identification of common features and situations in the cultures in which they operate, we may say that the items have the same application". 5. The surprising fact is that Juliane House’s basic concept of text function has been relatively little used or explored in North America. This is perhaps due to the fact that she has integrated it into a model for translation quality assessment - which is not a popular field of research in the North American context. 6. This definition is an adaptation of Juliane House’s definition of the function of text (1977: 37), cited above. 7. The various reasons that led André Gide to translate or initiate the translation of different literary texts are analyzed by Johanne Blais in an unpublished M.A. thesis (1981: 7-64). 8. A more detailed analysis of different French translations of De Quincey’s Confessions is found in André Taillefer’s M.A. thesis (1981). References Blais, Johanne. 1981. André Gide et la traduction. Ottawa: University of Ott8wa. [Unpublished. M.A. thesis.]. Baudelaire, Charles. 1964. Les Paradis artificiels. Paris: Gallimard. Baudelaire, Charles. 1973. Correspondance. Paris: Gallimard, "Bibliothèque de la Pléiade". Bühler, Karl. 1965. Sprachtheorie. 2nd ed. Stuttgart: Fischer. Crystal, D. and D. Davy. 1969. Investigating English Style. London: Longman. . De Quincey, Thomas. 1962. Les Confessions d’un opiomane anglais, suivies de Suspiria de Profundis et de la Malle-Poste anglaise, tr. Pierre Leyris. Paris: Gallimard, "Collection NRF". De Quincey, Thomas. 1964. The Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, tr. Françoise Moreux. Paris: Aubier, "Collection bilingue des c1assiques étrangers". Halliday, M.A.K. 1973. Explorations in the Functions of Language. Victoria, Australia: Edward Arnold. Halliday, M.A.K. 1978. Language as Social Semiotic. Baltimore: University Park Press. Harvey, Anthony (ed). 1959. The Penguin Book of French Verse 4. Harmondsworth: Penguin. House, Juliane. 1977. A Model for Translation Quality Assessment. Tübingen: Gunter Jakobson, Roman. 1960. "Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics". Th.A. Sebeok, ed. Style in Language. Cambridge, Mass.: M.I.T. Press, 1960. 350-377. Leyris, Pierre. See De Quincey 1962. Lyons, John. 1968. Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Moreux, Françoise. See De Quincey 1964. Musset; Alfred. 1960; (Euvres completes en pro se. Paris: Gallimard, "La Pleiade". Newmark, Peter. 1981. Approaches to Translation. Oxford: Pergamon Press. Nida, Eugene A. and Charles Taber. 1969. The Theory and Practice of Translation. Leiden: E.J. Brill. Pichois, Claude. 1964. Introduction to Charles Baudelaire, Les Paradis artificiels. Paris:Gallimard, 1964. 7-21. Porche, F. 1944. Baudelaire. Paris: Flammarion. Reiβ, Katharina and Hans J. Vermeer. 1984. Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Translationstheorie. Tübingen: Niemeyer. . Sager, Juan Carlos. 1983. "Quality and Standards - the Evaluation of Translations". Catriona Picken, ed. The Translator’s Handbook. London: Aslib, 1983. 121-128. Taillefer, André. 1981. Les Traductions françaises des Confessions of an English Opium-Eater de Thomas De Quincey: considérations historiques, linguistiques et psycholinguistiques. Ottawa: University of Ottawa. (Unpublished M.A. thesis.] Toper, Pavel. 1978. "The Achievements of the Theory of Literary Translation". Paul Horguelin, ed. Translating, A Profession: Proceedings of the Eighth World Congress of the International Federation of Translators, Montreal 1977. Montreal: CTIC, 1978. 41-47. Toury, Gideon. 1980. In Search of a Theory of Translation. Tel Aviv: The Porter Institute for Poetics and Semiotics. Toury, Gideon. 1984. "Translation, Literary Translation and Pseudotranslation". E.S. Schaffer, ed. Comparative Criticism 6. Cambridge University Press, 1984. 73-85. Toury, Gideon. 1989. "Well, What About a LINGUlSTIC Theory of LITERARY Translation?" Bulletin ClLA 49. 102-105. Zola, Émile. 1923. L’Assommoir. 2 vols. Paris: Charpentier. Zola, Émile. 1971. Le Roman experimental. Paris: Garnier-Flammarion.