Improving Water Quality in the Big Blue River Basin, Nebraska and

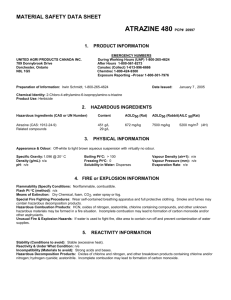

advertisement

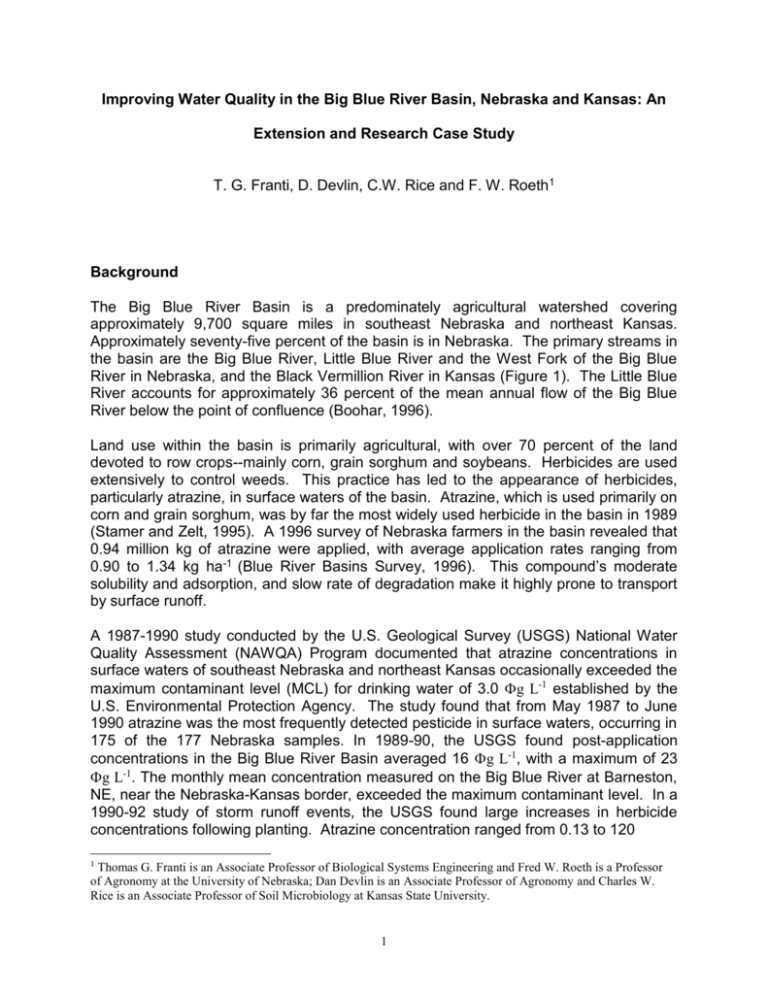

Improving Water Quality in the Big Blue River Basin, Nebraska and Kansas: An Extension and Research Case Study T. G. Franti, D. Devlin, C.W. Rice and F. W. Roeth1 Background The Big Blue River Basin is a predominately agricultural watershed covering approximately 9,700 square miles in southeast Nebraska and northeast Kansas. Approximately seventy-five percent of the basin is in Nebraska. The primary streams in the basin are the Big Blue River, Little Blue River and the West Fork of the Big Blue River in Nebraska, and the Black Vermillion River in Kansas (Figure 1). The Little Blue River accounts for approximately 36 percent of the mean annual flow of the Big Blue River below the point of confluence (Boohar, 1996). Land use within the basin is primarily agricultural, with over 70 percent of the land devoted to row crops--mainly corn, grain sorghum and soybeans. Herbicides are used extensively to control weeds. This practice has led to the appearance of herbicides, particularly atrazine, in surface waters of the basin. Atrazine, which is used primarily on corn and grain sorghum, was by far the most widely used herbicide in the basin in 1989 (Stamer and Zelt, 1995). A 1996 survey of Nebraska farmers in the basin revealed that 0.94 million kg of atrazine were applied, with average application rates ranging from 0.90 to 1.34 kg ha-1 (Blue River Basins Survey, 1996). This compound’s moderate solubility and adsorption, and slow rate of degradation make it highly prone to transport by surface runoff. A 1987-1990 study conducted by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) National Water Quality Assessment (NAWQA) Program documented that atrazine concentrations in surface waters of southeast Nebraska and northeast Kansas occasionally exceeded the maximum contaminant level (MCL) for drinking water of 3.0 g L-1 established by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The study found that from May 1987 to June 1990 atrazine was the most frequently detected pesticide in surface waters, occurring in 175 of the 177 Nebraska samples. In 1989-90, the USGS found post-application concentrations in the Big Blue River Basin averaged 16 g L-1, with a maximum of 23 g L-1. The monthly mean concentration measured on the Big Blue River at Barneston, NE, near the Nebraska-Kansas border, exceeded the maximum contaminant level. In a 1990-92 study of storm runoff events, the USGS found large increases in herbicide concentrations following planting. Atrazine concentration ranged from 0.13 to 120 1 Thomas G. Franti is an Associate Professor of Biological Systems Engineering and Fred W. Roeth is a Professor of Agronomy at the University of Nebraska; Dan Devlin is an Associate Professor of Agronomy and Charles W. Rice is an Associate Professor of Soil Microbiology at Kansas State University. 1 g L-1, with the largest concentrations generally occurring in May and June (Frankforter, 1994). These exceedences are of particular concern for public drinking water supplies because atrazine is not effectively removed by conventional water treatment. Tuttle Creek Lake, located on the Big Blue River approximately 17 kilometers upstream from its confluence with the Kansas River, is a source of public drinking water. In addition, public water supplies for the cities of Topeka, Lawrence, and Kansas City, Kansas, are withdrawn from the Kansas River downstream of its confluence with the Big Blue River, a source of water for over 250,000 people. High concentrations of atrazine in the Big Blue River can cause atrazine concentrations in the Kansas River to exceed 3.0 g L-1 (Stamer and Zelt, 1994). Land Use Because land use determines where atrazine is applied, it has a large impact on atrazine occurrence in surface waters. In the Nebraska portion of the Big Blue River Basin, the predominant land use is cropland, at 77 percent, of which 41 percent is irrigated. Irrigated cropland dominates the central and western portions of the basin, north of the Little Blue River. South of the Little Blue River in Nebraska, dryland cropland, pasture and range are the most common land uses. In the eastern part of the basin in Nebraska, dryland cropland and pastureland are prevalent. In the Kansas portion of the basin, cropland is also the dominant land use, 60 percent, although pasture and range is also common. Only 3% of Kansas cropland is irrigated. Corn and grain sorghum are the two main crops on which atrazine is applied. Thus, at a regional scale the distribution of these two crops can be used to estimate the distribution of atrazine applications. Overall, production of corn and grain sorghum is significantly greater in the Nebraska portion of the Big Blue River Basin, with 46 percent of land area, or 866,350 hectares, than in the Kansas portion, with 19 percent of land area, or 118,400 hectares. In general, the northwest part of the basin has the greatest percentage of corn, much of which is irrigated. Values range from a high of 62% in Hamilton County, Nebraska, in the northwest portion of the basin, to a low of 1% in Riley County, Kansas, in the southernmost portion. For grain sorghum, values are generally greatest in the eastern portion of the basin and lowest in the west-northwest and south, ranging from a high of 29% in Gage County, Nebraska, to lows of 4% in Hamilton and Kearney Counties, Nebraska. The Blue River Basin is an example of an interstate water quality problem. The larger geographic area and cropland area is in Nebraska, and contributes atrazine runoff to reservoirs in Kansas, which are used for a drinking water source. Atrazine concentrations in Kansas have the potential to exceed maximum contaminant levels, potentially causing municipal water supplies to be out of compliance with water quality standards. A two-state effort was needed to develop a solution to this problem. To reduce atrazine runoff in the basin, a three-part effort was developed: (1) partnerships 2 among agencies and organizations; (2) education programs and demonstration projects; and, (3) research into more effective atrazine management practices. Summary of Problem Statement The Blue River Basin is a 9,700 square mile agricultural watershed in Southeast Nebraska and Northeast Kansas. Approximately three-quarters of the basin is in Nebraska. Surface water drains to Tuttle Creek Lake, near Manhattan, Kansas. In the late 1980s through the mid-1990s, several United States Geological Survey studies documented concentrations of atrazine in surface water that occasionally exceeded the maximum contaminant level for atrazine in drinking water. These levels pose a regulatory and economic threat to water use because water from Tuttle Creek Lake becomes a drinking water source for Topeka and Kansas City, Kansas. In the early1990s several groups in Nebraska and Kansas identified this problem as one that could be solved by public education and applied research. Because of the political and legal nature of this two-state watershed issue, coordination between groups in Nebraska and Kansas was imperative. Partnership Efforts Reducing atrazine runoff in the basin has been the result of many partners working together. The University of Nebraska and Kansas State University have developed joint research and extension programming. Nebraska Natural Resources Districts have implemented local surface water monitoring projects. Novartis Crop Protection and DuPont Agricultural Products have assisted private associations and the universities to complete research, education and surface water monitoring projects. And state agencies from both Nebraska and Kansas have developed and completed the Blue River Basins Agricultural Survey. These partnerships have focused both attention and resources on this issue, and have established the Blue River Basins Project as a model for collaborative effort. The following sections detail several program activities completed in cooperation with partners that have made this project a success. In 1994, a joint Kansas and Nebraska ad hoc committee was formed which had the long-term goal of reducing atrazine runoff in the Blue River Basin through the adoption of best management practices by farmers. This group included representatives from agencies and organizations in both states, including the respective Departments of Agriculture, University Cooperative Extension, Corn and Grain Sorghum Producer’s Associations and the Agricultural Statistics Services. Three objectives were established by the committee: 1) conduct a farmer survey to understand current atrazine management practices and regional differences in practices, 2) establish a surface water monitoring program in both states, and 3) develop atrazine best management practice recommendations for farmers that are effective in the diverse production systems within the basin. To date, all of these objectives have been met. 3 In 1996 over 400 farmers were surveyed in Nebraska and Kansas for the Blue River Basins Survey (1996). Collaborating on this project were the state Departments of Agriculture from Nebraska and Kansas, the Agricultural Statistics Service, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Results of the survey provide a measure of best management practice adoption and baseline to measure future changes. A Blue River Basins surface water monitoring plan was developed to evaluate atrazine loading from several major tributaries in the basin. The plan was implemented in 1997 with substantial private and public financial support from Novartis Crop Protection, Nebraska Department of Environmental Quality, Kansas Department of Health and Environment, and Kansas State University. Monitoring has continued through 1999. Kansas State University (KSU) and the University of Nebraska (UN) Cooperative Extension have research and extension projects directed at reducing atrazine loading in the Blue River Basins (BRB). Both states have formed interdisciplinary action teams focusing on improving surface water quality in the BRB, and, specifically, reducing atrazine runoff. As part of this effort, a joint UN and KSU collaborative project was formed. This initiative includes a joint coordinating committee that provides guidance for extension, research and monitoring in the two states. The objectives of the projects are to: 1) identify target subwatersheds with high potential atrazine and sediment loading using existing data, 2) obtain atrazine and sediment loading data from target subwatersheds and model critical areas, 3) collaborate with partners to improve and expand the use of known best management practices (BMP) in target subwatersheds, and 4) generate additional funding for BMP research, education and demonstration projects. To date, work on all objectives is complete or on-going. Two watersheds in Nebraska, the Indian Creek Watershed in Fillmore County, NE, and the Upper Turkey Creek Watershed in Saline County, NE, and two watersheds in Kansas, the Little Blue River Watershed in Washington County, KS, and the Horseshoe Creek Watershed in Marshall County, KS, have been targeted for surface water quality monitoring and extension education programming. Surface water quality sampling was conducted in these watersheds in 1997-1999, and, in Kansas, extension education programming was begun in 1998. Additional funding has been received through outside grants. Grants include: 1) a joint research project between Kansas State University and the University of Nebraska; 2) extension education projects in Nebraska; and 3) a grant through the USDA Fund for Rural America for both research and extension efforts in the basin. The USDA grant shows that this watershed issue has a nationally recognized stature. In 1996, the Nebraska Corn Growers Association initiated a 2-year education project to promote adoption of atrazine best management practices by Nebraska corn producers. This was the first grower initiated program of its kind. Partners included Cooperative Extension and Novartis Crop Protection. The Blue River Basin was a primary target area for this project. In 1997, the Kansas Corn Growers Association in cooperation with 4 Kansas Cooperative Extension initiated an educational project to identify farmers that were currently using recommended best management practices for atrazine who would act as mentors for other farmers. How Research and Extension was Harnessed to Solve the Problem: Nebraska Perspective Extension education programs in soil and water management and conservation have a dramatic and sustained history in Nebraska. Throughout the 1980’s and into the 1990’s soil conservation efforts were strong particularly in the area of conservation tillage. A state-wide Cooperative Extension effort provided awareness of the need for adopting conservation tillage and hands-on training in adapting existing equipment and using new tillage implements. This effort was very successful in the Blue River Basins. Local programs, workshops, field days and farmer contacts were the primary method of education. Based on a 1996 survey (Blue River Basins Survey, 1996) 14% of farmers use no-till, defined as no soil disturbance from harvest to planting, except for anhydrous ammonia injection, 21% use ridge-till, and 15% use minimum-till, defined as one to two disk-till passes per year. The wide spread adoption of conservation tillage was the framework for the adoption of atrazine management practices. The project goal was to recommend best management practices to reduce atrazine while still maintaining conservation tillage practices. Local Best Management Practices A best management practice can be defined by four criteria: 1) effectively reduces the runoff of nonpoint source pollution; 2) is willingly adopted by farmers because it can fit their current tillage and management practices; 3) is cost-effective; and 4) does not create a related resource problem. In the case of best management practices for atrazine, fitting recommendations to various tillage practices was essential to meet criteria of willing adoption and not creating related problems. For example, asking farmers to incorporate atrazine by tillage below the soil surface in erosion prone soils may be counter productive to a soil conservation plan. The first step in the education process was to develop best management practice recommendations that would fit all four criteria. Recognizing that these recommendations would change depending on the location in the watershed, the first effort was to involve local farmers to assist in developing the recommendations. A process was followed similar to one used in Colorado by Walker and Waskom (1994), wherein a long-term advisory committee of farmers assisted educators and policy makers in developing locally appropriate best management practices. The process used in the Blue River Basin differed, in that three locally-based producer meetings were used to discuss and develop the best management practices suited to a local region of the watershed. These groups were composed of farmers considered at 5 Local Best Management Practices The wide spread adoption of conservation tillage was the framework for the adoption of atrazine management practices. The project goal was to recommend best management practices to reduce atrazine while still maintaining conservation tillage practices. A best management practice can be defined by four criteria: 1) effectively reduces the runoff of nonpoint source pollution; 2) is willingly adopted by farmers because it can fit their current tillage and management practices; 3) is cost-effective; and 4) does not create a related resource problem. the forefront in their region at adopting atrazine use best management practices, as well as some who were good conservation farmers. The final recommendations made were based on: 1) what research suggested were good practices to reduce atrazine runoff; 2) what best management practices farmers were currently using; and, 3) what the group suggested would be adopted throughout the local area based on common, locally used tillage and management practices. The results of these meetings were published as fact sheets for distribution in the local areas of the basin. Research While this best management practice recommendation process was occurring, funding for research on alternative practices was sought. Grants were received to evaluate the impact of tillage on atrazine runoff in the Blue River Basins. The project consisted of field plots (0.01-0.10 hectares) that were in three different tillage practices: ridge-till, notill and disc-till. Natural rainfall/runoff was measured from these plots and water samples were collected to determine the atrazine concentration of the runoff. Total water runoff and atrazine mass loss was computed, and the data was used to calibrate and validate the GLEAMS computer model (Leonard et. al., 1987). Fifty-year simulations of atrazine runoff were completed for 10 different combinations of tillage and herbicide application practices. The long-term results were compared and best management practices recommendations were made based on the computer modeling results (Fig. 2). The model results allowed for the comparison of long-term runoff trends among various practices that would be impossible with field plot studies because of the time and expense involved. This assessment showed that some of the practices previously recommended as effective for reducing atrazine losses actually were not. For example, split application did not significantly reduce long-term losses compared to pre-emergence application. Extension Education Efforts The producer-based best management practice and modeling results recommendations were provided to farmers through various extension programs and methods, including factsheets, field days, and presentations. Many of these programs were done in collaboration with other partners in the project. One key aspect of the Blue River Basins project that has made it a success is the number of different partners (groups) that have come together to focus some effort on the issues. Two private chemical companies, Novartis and DuPont, each sponsored field days and farmer education meetings; 6 grower associations, including the Nebraska and Kansas Corn Growers and Grain Sorghum Growers Associations made best management practice education a priority and sponsored field days, education publications and developed strong advocacy programs in their organizations; state agencies, including the Nebraska Department of Environmental Quality and the Kansas Department of Agriculture were involved in developing and implementing farmer surveys and water monitoring programs in the basin; and, finally, local watershed management districts in Nebraska (Natural Resources Districts) collaborated with in-kind activity, program support and financial assistance. Cooperative Extension, through county-based staff and programming was able to reach the farmer audience. However, rather than develop new meetings and programs that farmers would have to attend to learn about best management practices, this information was shared during regular meetings and in conjunction with meetings that covered a range of agronomic topics. One aspect of the Blue River Basins Project that made this possible was the water quality training provided to the county-level extension educators (agents). For three years in a row, a one-day training session on pesticides and water quality was offered for educators. Over 30 educators attended this training, 12 who had assignments in the Blue River Basin. The training covered pesticide movement, best management practices, herbicide selection guidelines and alternative products. When educators competed the training they received a set of annotated slides and factsheets to use as educational aids in their local areas. The role of Cooperative Extension was to provide and support education programs to improve surface water quality. Much assistance and support was directed at two primary audiences: extension educators and natural resources agency personnel. This approach of “training the trainer,” that is, providing education to educators and technology transfer specialists who can then impact more farmers, and hectares, than one single person, has allowed these groups to direct their efforts toward the promotion of best management practices for reducing atrazine runoff in the basin. In addition to education programs and presentations provided by Extension educators, a field demonstration project was set up in one of the targeted subwatersheds. The Indian Creek Watershed Water Quality Demonstration project was not designed to illustrate side-by-side comparisons of alternate practices, but to provide large-scale, real The Role of Cooperative Extension The role of Cooperative Extension was to provide and support education programs to improve surface water quality. Much assistance and support was directed at two primary audiences: extension educators and natural resources agency personnel. This approach of “training the trainer,” that is, providing education to educators and technology transfer specialists who can then impact more farmers, and hectares, than one single person, has allowed these groups to direct their efforts toward the promotion of best management practices for reducing atrazine runoff in the basin. 7 world demonstration fields for farmers to visit, and to provide fact sheets with the description of the production practices, costs of weed control and owner/cooperator’s comments about the practice. The goal was to show that atrazine best management practices were being used and these were effective for weed control. A local guidance team of farmers, crop consultants and chemical dealers was formed to help select and implement the demonstration sites. The project illustrated best management practices on four fields in 1998 and nine fields in 1999. Results The targeted impact of the Blue River Basins program was farmer adoption of atrazine best management practices to reduce the potential for atrazine to leave a field. This will ultimately result in improved environmental conditions with less atrazine in surface water. Adoption of best management practices has resulted in reduced quantities of atrazine applied in the Blue River Basin. The reduction is a result of several practices: 1) use of combination herbicides that contain atrazine at lower application rates; 2) use of a band application method, which applies herbicides over only half the soil surface area as a broadcast application; and 3) use of alternative herbicides that do not contain atrazine. These practices have been promoted as best management practices in the basin. The Blue River Basins Survey (1996) indicates the adoption rate of combination products is over 80%, adoption of band application is over 70% and adoption of alternative herbicides is 12%. These adoption rates suggest that atrazine management practices in the basin have changed (as described below) and the potential for atrazine runoff to surface water is reduced A 1992 survey (Zoubek, 1993) provides an assessment of what farmers were doing before basin-wide education efforts began. The survey of 40 farmers in the Recharge Lake Watershed in York County, Nebraska, indicated that the average atrazine use rate among irrigated corn farmers was 1.9 kg ha-1, and that band application was practiced by 63% of farmers. After three years of education efforts by Zoubek and others, followup surveys in 1996 with 36 farmers indicated that rates were reduced by 50%, to 0.90 kg ha-1. Banding was reported by 53% of farmers. Education efforts on the Blue River Basins Project started in 1995. Farmer surveys from 1996 to 1998 indicate results similar to Zoubek. A 1997 survey of 41 farmers in the Indian Creek Watershed in Fillmore County, NE, indicated atrazine use rates were 0.90 kg ha-1 on irrigated corn and 0.74 kg ha-1 on dryland corn. Band application was used on 68% of irrigated corn hectares and 87% of dryland corn hectares. The 1996 Blue River Basin Agricultural survey of over 300 farmers indicated that the overall atrazine application rate in the upper basin, which includes both the Recharge Lake and Indian Creek Watersheds, was 0.96 kg ha-1 and banding was practiced on 80% of 8 hectares. These results indicate that, since 1992, education efforts have helped atrazine use rates decline and band application rates increase within the upper basin. Other areas of the basin show adoption of different best management practices compared to the upper basin. The Blue River Basins Survey (1996) indicated that in the lower basin the best management practices of band application and incorporation accounted for 41% of the hectares. A 1996 random survey of 9 corn fields in southern Gage County indicated 30% of hectares received band applications and 70% received broadcast applications, including 25% pre-plant broadcast. A 1998 follow-up survey of 10 corn fields, indicated 28% of hectares received band application and 45% received early-pre-plant application. While adoption of banding did not increase, the adoption of early-pre-plant application increased to 45% of hectares. Early-pre-plant application is a best management practice for this region, and together with band application accounts for 73% of hectares applied in 1998, compared to 70% broadcast applied in 1996. This indicates a rate of best management practice adoption similar to the upper basin. How Research and Extension was Harnessed to Solve the Problem: Kansas Perspective Atrazine runoff into surface waters was recognized as a problem in Kansas in the late 1980’s. Research programs were initiated at that time to study atrazine runoff and leaching from Kansas crop fields. Atrazine runoff losses were found to average 1 to 3% of applied atrazine. Factors influencing atrazine runoff were evaluated, best management practices were identified, and extension publications written to explain the atrazine best management practices and to help farmers adopt best management practices. By the early 1990’s, surface water monitoring showed that the Delaware River Basin in northeast Kansas had annual atrazine concentrations above 3 gL-1. For that reason, the first Pesticide Management Area (PMA) for surface water in the U.S. was declared for atrazine in the Delaware River Basin in 1994. A plan was developed to reduce atrazine concentrations in the surface water. The plan included intensive water monitoring, new regulations, atrazine best management practice research, and farmer education. Kansas State University had responsibility for monitoring, research, and education programs. By 1996, monitoring had identified subwatersheds in the Delaware River Basin that were contributing the greatest concentrations of atrazine runoff, and extension education programs were targeted to farmers in those watersheds. In late 1996, an advisory committee was formed that consisted of state agency, agribusiness, and university personnel and local farmers. County extension agents in the targeted watersheds were trained on atrazine best management practices using tours of research sites and classroom training. County extension agents met one-on-one with pesticide dealers and with a majority of the farmers in the targeted watersheds. Atrazine best management practices were taught to farmers at seven farmer meetings. Six demonstration plots were established and eight plot tours were held for farmers and 9 pesticide dealers designed to teach about atrazine best management practices and herbicide alternatives to atrazine. Additionally, best management practices publications were developed for farmers and news releases sent to newspapers within the targeted watersheds. By 1999 the educational program had shown positive results. Ninety-five percent of the farmers in the targeted watersheds had adopted Kansas State University’s recommended best management practices for atrazine. In addition, surface water monitoring indicated that reductions in atrazine concentrations in surface water in the targeted watersheds had occurred. Because the river basins are near each other and have similar land use, the experience gained in the Delaware Basin was used when attention was focused on the Blue River Basin. Efforts in the Kansas portion of the Blue River Basin began with the development a joint Kansas and Nebraska ad hoc committee in 1994 as described previously. The Blue River Basins cropping practices survey (Blue River Basins Survey, 1996) provided information on farmer practices and needs. A multi-year action plan was developed using an advisory committee consisting of state agency, university personnel and farmer representatives. Subwatersheds were targeted in Washington County, KS and Marshall Co., KS. A research and demonstration site was established in 1998 on a farm field in Washington County, KS, to evaluate and demonstrate atrazine and other crop management best management practices. This site has been used numerous times to train county extension agents, government agency personnel, and farmers. Numerous extension education programs were used in the Blue River Basin including: 1) county extension agents meeting one-on-one with 50% (55 farmers) of the farmers in the targeted watersheds to assist them with adopting atrazine best management practices; 2) four demonstration plots were established and tours conducted to teach farmers best management practices; and 3) four classroom farmer schools were held in the targeted watersheds. Farmer awareness of water quality concerns and recommended best management practices has increased. It is still too soon to tell if improvements in water quality have occurred, but adoption of best management practices is occurring. This research and extension program will continue through 2002. Summary Both Extension education and research efforts have contributed to increasing the adoption rate of best management practices throughout the basin. This has been from the efforts of many groups and individuals providing education and incentive to make changes. Coordination between two states, in university research, state agency efforts, and program focus of private organizations, has contributed toward the solution of this two-state problem. Results show that adoption of atrazine best management practices is occurring in the basin. Continued education efforts will increase adoption and reduce the atrazine runoff that may impact downstream drinking water sources. 10 References Blue River Basins Survey. 1996. Big Blue/Little Blue River Basin Farming Practices Survey, Nebraska Department of Agriculture, Division of Agricultural Statistics, 78 pp. Boohar, J.A., C.G. Hoy and F.J. Jelinek. 1996. Water Resources Data - Nebraska, Water Year 1995. US Geological Survey, Water Resources Division, Lincoln, Nebraska. USGS Water-Data Report NE-95-1, May 1996. Frankforter, J.D. 1994. Compilation of atrazine and selected herbicide data from previous surface water quality investigations within the Big Blue River Basin, NE, 19831992. U.S. Geological Survey Open File report 94-100. Leonard, R.A., W.G. Knisel, and D.A. Still. 1987. GLEAMS: Groundwater loading effects of agricultural management systems. Trans of the ASAE. 30 (5): 1403-1418 Stamer, J.K. and R.B. Zelt. 1994. Organonitrogen herbicides in the lower Kansas River Basin. Journal of the American Water Works Association, January 1994. Stamer, J.K. and R.B. Zelt. 1995. Herbicides and insecticides. In J.O Helgesen (ed.) Surface-water-quality assessment of the Lower Kansas River Basin, Kansas and Nebraska: Results of Investigations, 1987-90. USGS Open-File Report 94-365, 129 pp. Walker, L.R. and R. Waskom. 1994. Involving agricultural producers in the development of localized best management practices. Presented at the 1994 ASAE International Meeting, Kansas City, MO, June 19-22, Paper No. 942089. Zoubek, G. 1993. A Baseline Study to Access Farm Operator’s Practices and Attitudes in the Recharge Lake Basin Drainage Area. Upper Big Blue Natural Resources District, York, Nebraska. 11