Arabic vowels

advertisement

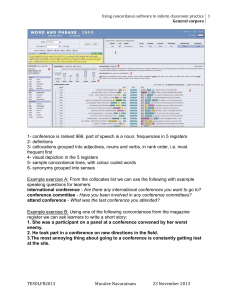

Mohammad Al Towaim MA Applied Linguistics Corpora in Language Teaching and Language Description Contents Introduction 1 Section 1: The Main Contributions of Corpora to Pedagogical Description 2 of Language and Language Teaching 1.1 Contribution of corpora to pedagogical description: 2 1.1.1 Corpora in lexical studies: 3 1.1.2 Corpora and grammatical studies: 5 1.2 Contribution of corpora to language teaching: 6 1.2.1 Corpora and the contents of language teaching 7 1.2.2 Corpora and language teaching methodology 8 Section 2: Using Corpora in the Language Classroom 9 2.1 Data-Driven Learning (DDL) 9 2.2 Discovery Learning (DL): 10 Section 3: Some Limitations of Using Corpora: 11 Conclusion 13 References 14 Introduction This essay will consider the position of Corpora in both language teaching and language description. In section 1, I am going to focus on the main contributions offered by corpora to a pedagogical description of language, especially to lexical and grammar studies. In the same section, the positive effect of corpora will be considered, regarding language teaching contents and methodology. After that, section 2 will illustrate the applications of corpora in the language classrooms, indicating some approaches. Then, the limitations of using corpora will be pointed out. Finally, the conclusion will summarise the essay. All of these features are focused on as an attempt to answer the following questions: What have been the main contributions of Corpora to language teaching and pedagogical description of language in recent years? Give appropriate examples. What are the limitations of Corpora as applied to language description and language learning and teaching? How might one use their outputs in the language classroom? 1 Section 1: The Main Contributions of Corpora to a Pedagogical Description of Language and Language Teaching Most linguists and many language teachers, as Granger (1994) said, are interested in corpora. Such a claim might be true, due to the importance of applications of corpora in both linguistic descriptive and language teaching. In this section, I am going to focus on the significant contributions offered by these applications, giving appropriate examples. 1.1 Contribution of corpora to pedagogical description: Kennedy (1998) says that the main reason for compiling corpus-based research is to present a trustworthy description of the usage of language and how it is structured. So, one could agree with Francis' definition of corpora, cited by Partington (1998:2) "A collection of texts assumed to be representative of a given language, dialect or other subset of a language, to be used for linguistic analysis". Moreover, the use of corpora in applied linguistics, according to Biber, Conrad and Reppen (1994), has two main advantages: 1. Rather than being based on intuition and perception, analyses depending on corpora are made on the ground of naturally-occurring structures and patterns of actual use. 2. In addition to quantitative analyses offered by using corpora, there are some new areas, such as register variation, which allow the researcher to investigate those areas. So, the discourse factors will govern the choice between structural variants. In the light of previous details, Partington (1998) indicates some of the main concepts that corpora focus on regarding linguistic description and analysis: i. Lexis. The main sort of corpus-based research into lexis, conducted using corpora, investigates the frequency of words and word senses in different types of text or language varieties and their collocational behavior, that is, their patterns of combination with other word. . 2 ii. Syntax. The patterns of combination of words in phrases, clauses or even sentences, can be investigated using corpora. Such studies have shown how a word, even each individual sense of word, appears in typical phraseologies. iii. Text. The description of linguistic phenomena at levels above that of the clause has, in contrast, received relatively scant attention, largely because the nature of the technology apparently facilities the study of discrete lexical items and sequence rather than larger stretches of language. iv. Spoken language. Corpora of spoken language have been used to study, among other things: pauses (Stenstrom 1990, cited in Partington, 1998), repetition and other non-fluencies (Stenstrom & Svartvik 1993, cited in Partington, 1998), hedging, back-channel responses and softeners (Altenberg 1990, cited in Partington, 1998). v. Translation studies. A number of "equivalent corpora" (i.e. corpora in two or more languages containing a similar text type) have been exploited to be used as sources of linguistic, semantic or pragmatic information to aid the process of translation. An example of this is the PIXI corpus (Gavioli & Mansfield (eds) 1990, cited in Partington, 1998), which consists of transcripts of interactions in Italian and British bookshops. vi. Register studies. Corpora can be used for comparing, not whole languages, but different varieties of the same language. The best-known work on comparing sublanguage is probably that carried out on register, by Biber and associates, (Biber 1988,1989; Biber, Conrad et al., 1994) who classify text types according to six communicatively defined "dimensions", and by Nakamura (1993), who describes methods of semi-automatically classifying texts according to type. vii. Lexicography. This is the area of corpus research which has had the greatest impact on English language pedagogy. The sheer wealth of authentic examples that corpora provide enables dictionary compilers to have a more accurate picture of the usage, frequency and, as it were, social weight of word or word sense. (Partington, 1998:2). 1.1.1 Corpora in Lexical Studies: By using corpora, lexicographers can choose among millions of examples of a word or phrase offered in few seconds. This means, according to McEnery and Wilson (1996), that a dictionary can be produced much more quickly than before. In addition, 3 the definitions might be more complete and precise, due to a larger number of natural samples examined. The relation between a node word and lexical set may, from a traditional point of view, have been defined in isolated instances. It is clear that a lexical relation which is not recorded systemically in either dictionaries or grammars cannot be captured by current descriptive theory. Such definitions, as Partington (1998) mentions, could be improved by means of corpora. In addition, corpus-based lexicographic research indicates that there is a different distribution between words and word senses among registers. So, our intuition about a word, in fact, cannot reach the real patterns of use. Sinclair (1991, cited in Biber, Conrad and Reppen, 1994) explains the previous point by an analysis of the word back. Biber, Conrad and Reppen (1994), referring to Sinclair's claim and result, say that most dictionaries consider the human body part as the core meaning of back. But such meaning is rare, since the COBUILD corpus show that the dictionaries' sequence of meaning is far from the actual use, which indicates that the most common meaning of back is the adverbial sense meaning 'in, to, or toward the original starting point, place or condition’. One of the most frequent uses of corpora for lexical description is, as Kennedy (1998) indicates, lexicography. Corpora can be a good associated in since it is used not only to identify the set of different words in a language, but it might be applied to identify the different uses of particular types and their relative frequencies. Such benefits mentioned above might appear in many examples. One of them is cited by McEnery and Wilson (1996). When Atkins and Levin (1995) focus on the verbs in the semantic class of 'shake', they take the definitions of these verbs from three dictionaries: the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary and the Collins COBUILD Dictionary. In that paper, they show how the dictionaries without considering Corpora had produced their information wrongly. For instance, two verbs, quake and quiver, are considered as intransitive verbs in both the Longman and COBUILD dictionaries. But such a claim is far from the reality, since Atkins and Levin discovered these verbs in a corpus of 50,000,000 words and found that both quake and quiver can be transitive (foe examples, It quaked her bowels; quivering her wings) as well as intransitive. 4 Another example is mentioned by Owen (1993). He considers the uses of take described by the COBUILD Dictionary as: 'The most frequent use of take is in expressions where it does not have a very distinct meaning of its own, but where most of the meaning is in the noun that follows it (i.e. its direct object)'. This definition could be true if it illustrated the cause of unacceptability of passive examples with take. However, the matter is not satisfied in all delexicalization examples, due to the fact that there are many delexicalized take structures in the passive. Owen (1993:176) says in more detail: “ …‘take’ is a verb which is used transitively in the great majority of instances, but a very large number of the direct objects which occur after it either cannot become the subject of the passive structure or can only do so under conditions which are as yet unclear…. Facts like these were known before the advent of computers, but lexicographic work using concordances based on large quantity of data has undoubtedly brought many more of them to light”' 1.1.2 Corpora and grammatical studies: In addition to lexical studies, grammatical (or syntactic) researches are one of the most common types of studies using corpora. Such usage might have obtained its significance because, as Biber, Conrad and Reppen (1994) claim, most materials used in the teaching of grammar have just been based on intuition rather than depending on deep study. In addition, McEnery & Wilson (1996) point out some reasons to declare the importance of using corpora in grammatical research: i. Corpora can represent the quantification of the grammar of all language variety. ii. Corpora's role, as empirical data, serves in the testing of the hypotheses resulting from grammatical theory. iii. As mentioned in lexical studies, the grammatical studies using corpora can present a real judgment of what usages are most typical and which variation occurs within, or across, varieties. iv. The grammatical theory can dovetail with corpora. For example, Michael Halliday's theory of systemic grammar is dependent on the notion of language as a paradigmatic system: that is, as a set of selects for each example, from which a 5 speaker should choose one. So, he claims, since such choices are inherently probabilistic, written English prefers which to that as a relativiser. When corpora examines such a claim it would be declared that it is true, since which is 39 % probable whereas that is 12 % probable. In the light of such significance, Biber (2001) point out that there are a lot of researches based on the corpora-based tools to discover English grammar and discourse. For example, Fox and Thompson (1990, cited in Biber, 2001) have applied corpora in their study of relative clauses. Another example is the research of the discourse and function of modal verbs, which was investigated by Myhill (1995, 1997, cited in Biber, 2001). . 1.2 Contribution of corpora to language teaching: All descriptive findings above have many implications for language teaching. Such information, as Kennedy (1998) points out, should influence many aspects of language teaching: i. The selection of what to teach, the sequencing of pedagogy and the items which are preferred to be taught, since the corpora is very useful for contents of instruction. ii. The descriptive contributions offered by corpora are considered as a guide for language teachers when they make sure about language and language use. A teacher might be able, through corpora, to recognize the likelihood of occurrence and frequency of use as a significant measure of usefulness. iii. Language teaching methodology, also, can be influenced by corpora studies. The authentic analysed texts, which are available on a corpus database, play an important role as a means for establish a suitable approach to make useful techniques. Moreover, such procedures might encourage self-access and individualized instruction. Points 1 and 3 will be considered later. In addition, corpora have a significant influence in the ESP field. For example, Partington (1998) declares that a large number of language teachers and researchers 6 have established their own corpora to help them in specific aims. This kind of small corpus has a positive impact on language teaching in a way which is more suitable than a large corpus. Partington cites Flowerdew's example (1993), which is a collection adapted from Biology lecture texts, used to teach English for undergraduate students attending classes in this particular area of science. The finding indicates the fact that there is a huge gap between word and structure frequencies in both; this small corpora and the large one, which is the ten-million word Birmingham COBUILD. Apart from the English Language, corpora can play an important role regarding teaching another languages. For instance, Welsh, which is a revival language, applies corpora since corpus-based research offers a great deal of distribution in both general and in special language. Ahmad and Davies (1997) indicate to some applied studies in their article, pointing out in conclusion that such research can promote teaching and learning Welsh, especially through the lexical resources which are based on authentic texts. 1.2.1 Corpora and the contents of language teaching: There is some evidence, according to Kennedy (1998), that the learners of language seem to read rather than to say or write what they might want. Furthermore, Kennedy, citing George (1965), states that most first year English courses usually produce some verb-forms, such as present progressive, which accounted for only 20% of all verb-forms involved in his Hyderabad corpus. Moreover, there is a mismatch between normal use of English and what the learners are exposed to in the text books of learning English. Such a claim is made in research by Holmes (1988, cited in Kennedy, 1998). That study is based on the comparison between a corpus analysis and the linguistic devices taught in textbooks for expressing epistematic modality. It is not just that the significant epistematic uses of modal verbs are absent: there is also almost an absence of pedagogical focus on the use of lexical verbs. So, one could argue, from such examples, that the corpora would have a positive impact when applied to the contents of language teaching curriculum and materials: " A major contribution of work in corpus linguistics to language teaching is thus to provide quantitative evidence on the distribution of the component parts of the language, as a yardstick against which to evaluate 7 subjective judgments about the goals and content of instruction. Kennedy (1998:288) 1.2.2 Corpora and language teaching methodology: Had a revival in the 1980's, some researchers such as Carter and McCarthy (1988, cited in Kennedy, 1998), consider the nature of lexicon and its pedagogical implications, and depending on such beliefs, the methodology of language teaching is influenced, especially in the teaching sequence. For example, Sinclair and Renoir (1988, cited in Kennedy, 1998), make an effort to declare that language learning should follow the sequence which is based on corpora studies to ensure that students obtain their language knowledge gradually. Kennedy (1998) also refers to another effort made by Willis (1990) who considers some commercial applications, based on the COBUILD project, to substantiate the role of lexis in syllabus design and language teaching methodology. 8 Section 2: Using Corpora in the Language Classroom Aston (1995) points out that the findings of corpora studies might have applications in the language classroom. Partington (1998:5) suggests two general approaches to applied corpora in the classroom: - Teachers can analyse the corpora themselves for material design; or; - they can decide to introduce them into the classroom and train students in their use. In the first case, Partington cites from Barlow (1996:30) that: "…teachers might use corpus-based investigation to (i) determine the most frequent patterns in a particular domain; (ii) enrich their knowledge of the language, perhaps in response to questions raised in the classroom; (iii) provide "authentic data" examples; and (iv) general teaching materials...” In the second: " … teachers may also wish to have their students explore corpora materials; either in following a path of investigation determined by the teacher (so that the student come to understand particular patterns of usage such as ‘say’ versus ‘tell’ or the collocations of ‘bright’, or in exploring an issue in a more open-ended way…” 2.1 Data-Driven Learning (DDL): Johan (1991, cited in Bernadini 2004) suggests this approach to show the suitable uses of corpora for language teachers and students, in which most work in this area, according to Bernardini (2004), owes something to Johan. By applying DDL, or "the learner as researcher" learning language moves from a deductive to an inductive process. Such an approach, as Partington (1998) points out, could make the learners' role more effective. Furthermore, many researchers, according to Aston (1995), declare that concordances allow for DDL 'data-driven learning', which can lead 9 students to deal, directly, with lexicogrammatical descriptions, in order to obtain examples by themselves, instead of take them from textbooks or teachers. 2.2 Discovery Learning (DL): Although the DDL has advantages, Bernardini (2004) considers the students as those who have the same level of interests, competences and capacities. Therefore, she suggests another approach, after examining it in the classrooms over many years. This approach is "Discovery Learning", or "The learner as traveller". Whilst the teacher in DDL has to be, as Partington (1998) cites Johan's term, "A director of student-initiated research, the teacher in DL should stop pretending to be the source of all knowledge, and students, on the other hand, should start to be active participants in the classroom.” DL encourages students to follow their interests and focus on form as well as meaning. It can serve not only learners, but also the teachers, especially if they are non-native speakers of the language they teach, since the teacher seems to be a learning expert rather than a language expert. 10 Section 3: Some Limitations of Using Corpora: Like all language teaching approaches, corpora, and its application, have some limitations which many researchers consider, such as: i. One of the most extreme critics is Cook (1998) who criticizes the linguists who "overreach themselves". In his short article, Cook points out many limitations, and one of them is that: a. "…Corpus statistics say nothing immeasurable, but crucial, factors such as students' and teachers' attitudes and expectations, the relationship between them, their own wishes, or the diversity of traditions from which they come…" Cook (1998:58) ii. On the other hand, the language studied by corpora is separated from its context. As Partington (1998) says, we typically do not know any thing about all the circumstances which are related to the text. iii. Owen (1996: 221) points out that : i. "… while teachers might believe that a better prescription will follow from more reliable description, in practice they would still have to decide which of the two (or more) descriptions they prefer." iv. Ferguson (2006:20) declares that: "corpora can present the danger of facile over-generalization. We need to remember that a corpus …does not represent the whole language…" v. The assumption that the language descriptions offered by corpora necessarily entail a better basis for language teaching is criticized by Widdowson (1991, cited in Aston, 1995), who points out that language learning cannot be based on the database or the description of language, 11 and such analyses, apart from the facts they produce; do not themselves have any guarantee of pedagogic relevance. vi. Regarding second language acquisition, Ferguson (2006:20) indicates that: " …corpora are based on native speakers speaking and writing; so the effect is that the collocations, formulae and patterns found are characteristic of native speakers usage and not of second language users… the danger is that relying on the description provided through these corpora may encourage the imposition of native speaker norms that are, in fact, inappropriate for second language users…" 12 Conclusion Some aspects related to corpora have been considered, in terms of both language description and language teaching. Alongside with the applications of corpora in the classroom, the limitations of the usage of corpora have been indicated. This topic is significant for me as a teacher of Arabic to foreign students, given the lack of this kind of study in Arabic. Thus, the question arises of how such techniques can be applied to Arabic. I hope to find some answers in future research. 13 References Ahmad, K & Davies A (1997) 'The Role of Corpus in Studying and Promoting Welsh'. In A. Wichmann, S. Fliegestone., T. McEnery & G. Knowles (eds.) Teaching and Language Corpora. London: Addison Wesley Longman. Aston, G (1995) 'Corpora in Language Pedagogy: Matching Theory and Practice'. In Cook, G (ed.) Principle & Practice in Applied Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bernardini, S (2004) 'Corpora in the Classroom: An Overview and Some Reflections on Future Developments'. In Sinclair, J (ed.) How to Use Corpora in Language Teaching. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing. Biber, D., Conrad, S. & Reppen R (1994) Corpus-Based Approaches and Issues in Applied Linguistics. Applied Linguistics 15: 169-189. Biber, D. (2001).'Using Corpus-based Methods to investigate Grammar and Use: Some Case Studies on the Use of Verbs in English', in Simpson, R & Swales J (ed.) Corpus Linguistics in North America. USA: The University of Michigan Press. p101. Cook, G. (1998) 'The Uses of Reality: A Reply to Ronald Carter'. ELT Journal 52: 57-64 Ferguson, G. (2006) Handout: ‘Lecture on Corpora in Applied Linguistics. University of Sheffield. Granger, S (1994) The learner corpus: a revaluation in applied linguistics. English Today 39:25-29. Kennedy, G (1998). An introduction to corpus linguistics. London: Addison Wesley Longman McEnery, T. & A. Wilson (1996) Corpus Linguistics. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press. 14 Owen, C (1993) Corpus-Based Grammar and the Heineken Effect: Lexico-grammatical Description for Language Learners. Applied Linguistics 14: 167-187. Owen, C (1996) Do Concordances Require to be Consulted? ELT Journal 50: 219-224 Partington, A. (1998) Patterns and meaning. Amsterdam: John Benjamins 15