Heterogeneous Catalyzed Polymer Hydrogenation in Oscillating

advertisement

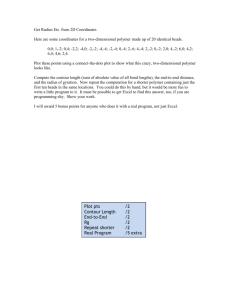

D1. Heterogeneous Catalyzed Polymer Hydrogenation in Oscillating Systems This project will: develop new techniques for polymer hydrogenation by incorporating novel reactor designs. One such design will implement oscillating conditions to address specific limitations of current methods. Primary Faculty Co-Advisors: Dr. Kerry Dooley, Chemical Engineering (Heterogeneous Catalysis) Dr. Carl Knopf, Chemical Engineering (Bubble Column Reactor) Dr. Dmitri Nikitopoulos, Mechanical Engineering (Two-Phase Flow) Off-campus Participant: Miguel Baltanas (University of Santa Fe and INCAPE Research Institute) Technical Proposal: Some 70% of the world polymer market is devoted to just four parent polymers: polystyrene (PS), polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyvinylchloride (PVC). With the flood of new plastics applications, these four simple polymers cannot satisfy the need for more specialized materials. Innovative uses demand elastomers that are stronger, better able to resist chemical attack, possess a wider temperature range of usage and better environmental stability, and are easy to produce. One way to produce a derivative with potentially improved attributes is through a post-polymerization reaction. Hydrogenations are just one type of modification that can “fit the bill” for creating new plastics. It is convenient because it builds on commercially available polymers and components, meaning no new investments are required for monomer production. One such example of a useful polymer formed upon hydrogenation of PS is polyvinylcyclohexane (PVCH). PVCH has a Tg that is 42 K higher than PS, meaning it can be used at elevated temperatures where PS would pass into its melt state and become soft. Another example is hydrogenated nitrile butadiene rubber (HNBR), which has superior resistance than standard NBR to degradation from prolonged oil contact and abrasion, even at elevated temperatures. The goal of this research is to advance the field of polymer hydrogenation by designing and executing new approaches to the catalysis/reactor design. One of the most widely studied hydrogenations is the reduction of a diene polymer, such as polybutadiene (Fig 1). Fig 1: Polybutadiene During this reaction, the olefinic double bonds in the parent polymer are hydrogenated until saturation is reached. The exact end product of hydrogenation largely depends on the configuration of repeating units in the polymer. Current hydrogenation techniques are severely limited in their ability to economically and efficiently produce hydrogenated elastomers. While diimide reduction using a hydrazide reagent is one way to hydrogenate certain polymers, almost all reactions are now carried out in the presence of a catalyst to improve reaction rates and make the process economically viable. Homogeneous Catalysis Many polymer hydrogenation reactions are carried out using homogeneous catalysis. The main advantages of this technique are mild reaction conditions (though not always the case), and the ability to better realize quantitative hydrogenation. The major disadvantages of this method are incomplete conversion to saturated polymer and the inherent difficulty in post-polymerization separation of catalyst from product. Over the past several decades, most hydrogenation research has been in homogeneous catalysis. Consequently, each hydrogenation reaction has been studied with many different transition metal complexes and solvents. The best choices for each respective reaction are generally understood. In fact, material on homogeneous polymer catalysis practically reads as a recipe book. Given that homogeneous methods are well known, the future of hydrogenation research lies in heterogeneous techniques. Heterogeneous Catalysis The shortcomings of homogeneous catalysis can be addressed by developing heterogeneous alternatives. Since heterogeneous catalysts do not in general impose undue separation requirements, they are clearly the desired choice. Unfortunately, several problems must be addressed before polymer hydrogenation by heterogeneous catalysis can reach its potential. The main problems are: 1. Catalyst Selectivity: Obviously, the desired catalyst must selectively catalyze hydrogenation as opposed to chain scission or side chain hydrodealkylation. However, at the extreme temperatures and pressures commonly found in current reactor systems, the catalyst often operates unselectively. For instance, PS hydrogenation to PVCH may require a temperature around 200ºC and pressures over 5 MPa while still taking about 3 h to achieve 90% conversion. Most of the literature does not deal with the selectivity issue directly. Instead, people work around it by finding alternative solvents or reaction conditions (e.g., low temperatures and addition of THF solvent) to abate side reactions. Currently, the only known sure way to limit chain scission is to keep temperatures low. 2. Leaching of Precious Metals: Because precious metals like Pt, Pd, and Ru are required, solvent leaching can be a serious problem. Constant replacement or regeneration of the catalysts is typically not economically viable. Therefore, the solvent/catalyst choice must be carefully screened for any corrosive tendencies. Despite its importance, most current research does not address the leaching issue. 3. Solvent Choice: Since the polymer must typically be dissolved in solution for the reaction to take place, the solvent choice is important. Solvents must be relatively cheap, noncorrosive, cannot contaminate the product, and must adequately dissolve the polymer reactant. By far the most popular solvents are decahydronaphthlalene (DHN) and tetrahydronaphthlalene (THN). Solvents containing oxygen, nitrogen, or sulfur are usually avoided as these tend to be difficult to separate from product. Certain fluorinated solvents will dissolve many polymers, but prolonged contact with H2 at high pressures can lead to undesired HF formation and safety concerns. Gehlsen et al. (1995) successfully conducted hydrogenation of PS homopolymers to synthesize PVCH derivatives using dilute cyclohexane solvent. For certain polymers such as PS and poly(α-methylstyrene) (PαMS), 10% (vol.) THF was added to enhance miscibility and prevent the large increase in polydispersity that was evident when DHN was used by Xu et al. (2003). Hucul et al. (1998) suggest that other saturated hydrocarbon solvents will work, but that cyclohexane is preferred for hydrogenating high molecular weight aromatic polymers. They do not explain why. Further research could lead to more discoveries on improved solvents for polymer hydrogenation. 4. High Pressure: One of the most severe problems that limit the application of heterogeneous catalysts is that high reactor pressures must be maintained. Pressures greater than 1 or even 10 MPa are not uncommon. For instance, Gehlsen et al. (1995) performed PS hydrogenation at 3.4 MPa. These high pressures are designed to overcome the mass transfer limitations encountered when hydrogen must first diffuse from the bulk gas into the bulk liquid solvent, then from the bulk solvent to the solid catalyst surface, and then into the catalyst pores (Fig 2). Fig2: Three phase mass transfer process 5. Catalyst Activity: There are two main problems related to activity. First, the catalyst often loses activity at the low temperatures (<350ºC) required to limit chain scissions. Second, the polymer chains are often entangled into shapes that have difficulty diffusing in and out of the tiny pore sizes of many “off the shelf” catalysts. In addition to entanglement phenomena, the relatively high viscosity of concentrated polymer solutions makes the problem worse. The result is that the polymer is often only exposed to the outer surface of the catalyst, which severely limits the area for reaction. One way to overcome this problem was discovered by Hucul et al. (2000). By using Pt on ultra-wide pore (UWP) silica (Fig 3), Dow created a catalyst that exhibits modest activity for PS hydrogenation at low temperatures (~150ºC) and relatively high polymer concentrations (~15-25% polymer by weight) with little to no chain degradation. This study can serve as a benchmark for the future work proposed below. The activity is mainly limited by the relatively low surface areas of such catalysts. Fig 3: TEM (right) and SEM (two on left) of Pt/SiO2 catalyst. Note the black Pt particles on the 0.1μm resolution TEM Hucul et al. (2000) performed the reaction in a slurry batch reactor by grinding the silica into a powder. The final product mixture could then still be separated by filtration or centrifugation. However, it would ultimately be desirable to eliminate this step. The Dow method required only a fraction of the time other catalysts needed to almost completely saturate PS. The UWP catalyst had a surface area of 16.5 m 2/g, a pore volume of 1.57 cm3/g, and an average pore diameter of 3800 Ǻ. Typically, catalysts with such large pores are avoided because of the correspondingly low surface areas. It would be beneficial if larger surface area materials could be used at different conditions. A specific example is 5 weight% Pd/BaSO4 catalyst with physical characteristics similar to those used by Xu et al. (2003) and Gehlsen et al. (1995). Ba and Pd can alloy, breaking up ensembles of sites that can cause chain scission. However, other alloying metals such as Zn and Cu can be used instead. Gehlsen et al. (1995) hydrogenated PS at 140ºC and 3.4 MPa H2. They were able to saturate PS homopolymers with only minor amounts of chain scission, although the reactions required >12 h contact times. The reactions of Xu et al. (2003) took less than 10 h, under conditions similar to Gehlsen et al. (except DHN solvent vs. 10% THF/cyclohexane for Gehlsen et al.). However, Xu et al. did observe significant scission as measured by changes in polydispersity. Rhodium and platinum are generally the most useful active metals for hydrogenation of polymers, although Pt is a poor catalyst for the hydrogenation of nitrile copolymers. Much still has to be learned about the relative activities of hydrogenation vs. chain scission, and about catalyst long-term degradation, in order to see what will really work economically. Outline of Proposed Research High pressures, high temperatures, excess solvent, selectivity and catalyst recovery issues invariably make the hydrogenation process expensive. In this project we suggest alternate routes for getting hydrogen to the surface of a heterogeneous catalyst at lower pressures and temperatures. A particular idea is to make use of a bubble column reactor where H2/liquid contact takes place at conditions associated with bubble resonance. At resonance conditions, increases in kla (the product of mass transfer coefficient and interfacial area) and gas holdup of >600% can take place at <3mm amplitudes in the airwater system (Ma, 2003). The measured values of kla are also significantly higher than equivalent values for a gas-liquid stirred tank at equivalent power/mass (Dooley, 2004). See Figure 4 below. The pulsatile flow induces gas bubble breakup by two mechanisms, one associated with induced shear at a sparger and the other associated with resonance stabilization of small bubbles in the bulk liquid. Current research in reactor design has tried to attain such resonant conditions by ultrasound, but not by using the mechanically attainable (piston/cam arrangement) frequencies (<50 Hz for the air/water system) that are proposed as part of this project. The reasons why are: (1) lack of understanding of the existing mass transfer literature on low frequency oscillating two phase flow; (2) failure to generate large enough amplitudes (at least ~1 mm is needed) with ultrasonic transducers or horns. However, high amplitude pulsed flows generated by flow modulation have been shown to greatly enhance reaction rates of gas/liquid reactions as long as the reactions are gas mass transfer limited (Khadlikar et al., 1999). This is the case for essentially all catalytic hydrogenations – polymeric or not. 0.03 0.025 0.02 klast k 0.015 klasp k 0.01 0.005 3.32410 4 0 0 0.032 2 4 6 PpM k 8 10 12 11.775 Figure 4. Experimental air-water kla values for oscillating bubble column (klasp), and equivalent values for a gas-liquid stirred tank (klast), vs. power/mass in m2/s3. The stirred tank values were computed from the Calderbank correlation. At this time, the mass transfer/reaction behavior of a two-phase polymer/bubble column or polymer/catalyst monolith system is not widely understood. Even a dilute polymer solution will have a higher viscosity than the simple air/water system (~0.4 cP) currently used in bubble column research. More concentrated polymer solutions or melts may exhibit large dampening effects on bubble resonance at typical hydrogenation conditions. Also, the higher viscosity will certainly increase the resistance to mass transfer, while also increasing gas holdup in the column. This has a two-fold effect. First, the increased resistance to mass transfer means the hydrogenation reaction is probably operating entirely in the gas mass transfer-limited regime. In reactor design terminology, the catalyst “wetting” by H2 is poor. Second, the increased holdup lowers the viscosity of the system somewhat, possibly leading to a higher interfacial area/volume (a), if a way such as bubble resonance can be found to decrease bubble size. In the air/water system, the increased holdup does not have important rheological implications. Instead, the increased holdup just increases “a”. But for viscous solutions, clearly, the hydrodynamic properties of the polymer solution in reactor channels and catalyst pores, and how these are affected by flow instabilities, will have an important impact on the behavior of the hydrogenation reaction. For high viscosity solutions, foaming may also take place, and the implications for reactor behavior are not clear at present. A different route for achieving better mass transfer but in existing processing equipment might be to conduct such reactions as part of a reactive extrusion. An extruder efficiently generates high pressures in the melt or concentrated solution, and vigorous mixing, while not allowing added gas to form isolated domains as is possible in an autoclave or bubble column. Therefore it could improve gas “wetting” of the catalyst. The extruder might also need to operate under oscillating conditions of gas flow, because the stoichiometric requirements of most polymer modification reactions require high gas to liquid volumetric ratios, and therefore operation in the slug-flow regime, in order to introduce the gas to the extruder. Such slugging can be controlled by pulsatile flow of either gas or liquid. The gas must be introduced at the “mixing” (low pressure region) of the extruder in order to prevent the backflow of polymer. Again, operating at even 30% lower pressures than current process practice, even with lower catalyst activities, would pay off economically. In general, almost all current research is locked into using either stirred tanks or trickle bed reactors at high pressures, either of which is quite expensive for large-scale use. While ongoing research for high molecular weight (>100,000) polymer hydrogenation does not seem too focused on the catalyst wetting problem (probably due to the use of homogeneous catalysts, or lack of implementation in pilot-scale plants), this is an important issue for the future that should be addressed. Overall, current research shows a strong relationship between the solvent/ polymer/ catalyst/ reactor design and how each of these influences polymer hydrogenation. The Dooley and Knopf labs will work together to address the problems outlined above associated with heterogeneous hydrogenation. We propose new methods to optimize polymer/catalyst/H2 contacting based on recent results for application of oscillating flow to gas-liquid contactors (Ma, 2003; Khadlikar et al., 1999). This will involve work on the oscillating bubble column first developed in the Knopf lab and on the vented extruder/torque rheometer and catalyst characterization equipment in the Dooley lab. Students involved in this project will receive hands on instruction in the related fields of polymer rheology, two-phase flows involving polymers, catalysis, and reactor design. Analytical tools such as GC, NMR, FTIR, TGA and BET will also be an integral part of research. By combining research ideas into a new direction, students will be able to offer ideas and test concepts that would not be feasible otherwise. Number of IGERT apprentices to be recruited and probable home departments: Two, both from Chemical Engineering, or one from Chemical and one from Mechanical Engineering. Consistency with the Macromolecular Education, Research & Training theme: This project requires students to understand catalyzed polymer hydrogenation reactions and how they can be carried out in actual reactors. It covers the advanced topic of how well different reactor systems can offer the desired reaction characteristics and end product. It applies some of the concepts and problems of polymers presented in the macromolecular classes to real systems, thus making this more of a “hands-on” project. How does the project form a vector cross-product of existing research themes by the participants? Existing research directions. Dr. Dooley has been researching heterogeneous catalysis for many years. Recently, he has also researched the incorporation of polymers to cement for improved processability. Therefore, integrating catalysis and polymers is an obvious addition to his research. Dr. Knopf is currently working with oscillating bubble column reactors and oscillating flows in catalyst monolith reactors. The bubble column represents one possible solution to hydrogenating polymers, with a particulate catalyst. The monolith reactor represents another, with a fixed bed catalyst. Other reactor configurations such as the vented extruder are available in Dr. Dooley’s lab. New research direction. The biggest research gain from taking a team approach comes from the ability of each team member to specialize in a different area of research appropriate for his background. For instance, Dr. Knopf’s knowledge of multiphase transport phenomena is useful in designing potential oscillating reactor systems; polymer hydrogenation is a logical extension of his past work on mass transfer in these systems. Dr. Dooley’s experience with heterogeneous catalysis and diffusion in porous media can be used to prepare the required catalysts and determine operating conditions. Dr. Nikitopoulos is an expert in two-phase flow. Hopefully, the results of this research will be applicable to industrial use in the future. Also, the IGERT team will merge ideas from chemistry and chemical engineering, resulting in a more diversified approach to this research. How do students benefit from the team-oriented research, beyond what would be available to them from either advisor separately? Polymer hydrogenation represents an excellent application for Dr. Knopf’s oscillatory flow multiphase contactors. Dr. Knopf’s oscillatory gas-liquid contacting research is still in its infancy and, while two systems have been constructed and one has been used for mass transfer and gas holdup studies, neither has been applied to any reactions of research interest. Polymer hydrogenation would be the first such reaction to be tested in this new type of contactor. However, this class of reaction could also be a model for future work in biodiesel hydrotreating and hydrocracking. A student working on the project would gain invaluable experience because he/she would be able to test the special characteristics of these reactors on reactions important on an industrial level. Similarly, by working as a team, students in Dr. Dooley’s group will gain access to the bubble column and monolith reactor for polymer hydrogenation. The students involved with the team will also be able to pass ideas between one another, and gain experience working in a group environment such as at a job. Hopefully, each student will gain knowledge about the different aspects of the project that they would not have gained if they worked alone. Briefly describe the support level available to each individual faculty or off-campus participant (i.e., without IGERT): All LSU faculty involved in the project are independently supported for research in related fields. More specifically, Dr. Dooley and Dr. Knopf have received unrestricted grants from various corporations for this research. Both professors are well funded and this guarantees that the graduate students have sufficient resources for research materials. Two oscillatory multiphase reactor systems (bubble column and catayst monolith reactor) are already available for this project. Interdisciplinary strengths of the team project: Dr. Dooley and Dr. Knopf have different research interests. Dr. Dooley’s specialty is catalysis, reaction engineering, and high pressure processing. Dr. Knopf works more in the field of computer aided design, high pressure processing, and multiphase contactors such as bubble columns. Dr. Nikitopoulos is an expert in two phase flow and is already working with Dr. Knopf to develop flow regime maps for two-phase oscillating systems. However, polymer hydrogenation is an area where all of their interests come together. This is because the project demands innovative catalyst design, novel reactor schemes, and attention to internals design in order to address the specific difficulties associated with polymer hydrogenation. Commitment of faculty & off-campus participants to work side-by-side with apprentices: Dr. Dooley, the BASF professor in the Chemical Engineering Department, is primarily an experimentalist. He frequently meets with students to discuss laboratory matters and answer questions. He spent the weeks over the winter holiday in the lab explaining the many pieces of experimental hardware. Included in his hands on demonstrations were: gas chromatography, surface area measurement, thermogravimetric analysis, extrusion, typical catalyst minireactors, and vacuum systems. In addition to learning use of typical lab instrumentation, many other valuable laboratory skills such as use of fittings, pumps, gas cylinder maintenance, and calcining furnaces were described. References: Dooley, K.M., personal communication, 2004. Hucul, D.A.; Hahn, S.F. “Catalytic Hydrogenation of Polystyrene”. Adv. Mater., 2000, 12(23), 1855-1858. Hucul, D.A. “Process for Hydrogenating Aromatic Polymers”. U.S. Patent, 1998, Patent No. 6,090,359, 1-12. Gehlsen, M.D.; Weimann, P.A.; Bates, F.S.; Harville, S.; Mays, J.W. “Synthesis and Characterization of Poly(vinylcyclohexane) Derivatives”. J. Polymer Sci. B: Polymer Phys., 1995, 33, 1527-1536. Khadilkar, M.R.; Al-Dahhan, M.H.; Dudukovic, M.P. “Parametric Study of UnsteadyState Flow Modulation in Trickle-bed Reactors”. Chem. Eng. Sci., 1999, 54, 2585-2595. Liu, W. “Ministructured Catalyst Bed for Gas-Liquid-Solid Multiphase Catalytic Reaction”. AIChE J, 2002, 48(7), 1519-1531. McManus, N.T.; Rempel, G.L. “Chemical Modification of Polymers: Catalytic Hydrogenation and Related Reactions”. J. Macromol. Sci. - Revs. Macromol. Chem. Phys., 1995, 35, 239-285. Ma, J. “Forced Bubble Columns”, M.S. Thesis, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, 2003. Mikkola, J.P.; Salmi, T. “Three-phase Catalytic Hydrogenation of Xylose to XylitolProlongling the Catalyst Activity by Means of On-line Ultrasonic Treatment”. Catal. Today, 2001, 64, 271-277. Xu, D.; Carbonell, R.G.; Kiserow, D.J.; Roberts, G.W. “Kinetic and Transport Processes in the Heterogeneous Catalytic Hydrogenation of Polystyrene”. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res., 2003, 42, 3509-3515.