ratner - International Law Students Association

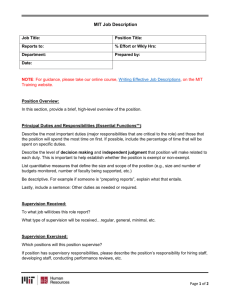

advertisement