ASPECTS OF MIGILI MORPHOLOGY

advertisement

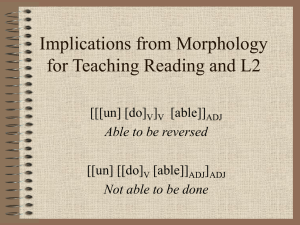

ASPECTS OF MIGILI MORPHOLOGY IDOWU KINGSLEY OYESUNKANMI 07/15CB057 A LONG ESSAY SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF LINGUISTICS AND NIGERIAN LANGUAGES, FACULTY OF ARTS, UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN. IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF A DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS (B.A. HONS) LINGUISTICS. MAY, 2011. CERTIFICATION This project work titled “Aspects of Migili Morphology”, has been read and approved as meeting the requirement for the award of the Degree, Bachelor of Arts (B. A. HONS) of the Department of Linguistics, Faculty of Arts, University of Ilorin, Nigeria. _______________________ ___________________ MRS. B. E AROKOYO DATE Supervisor ________________________ ___________________ PROF. A. S. ABDUSSALAM DATE Head of Department _______________________ ____________________ EXTERNAL EXAMINER DATE ii DEDICATION I thankfully dedicate this long essay to the almighty God, by whose infinite mercy I am alive. Also, I cannot but thank my parents Mr and Mrs Idowu for the love and care which they have shown me through their support. May God bless you and enlarge your coast. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS All glory and honour be unto God for if he had not been on my side, I would have been a reputable failure. My heartfelt gratitude goes to my amiable and understanding supervisor, Mrs Arokoyo. I pray your children will always find favour in Gods’ and mans’ sight. I am also thankful to my informant, Mr Ayuba , for his help. May God be with you wherever you are. My deepest appreciation goes to my parents and siblings, for showing me the love and care that I deserve. Ajiboye, Tinuoye and Oyedotun Idowu, I love you all and will always do, till death do us part. I will be an ingrate if I do not appreciate the support and help of my friends Okun Wayne, Nappy buoy, Kenny Geezle , Drey,Bayarnni, D Blak, Mayor, Pappaz, wale, Sleek Tee, my girlfriend Bukky, Seyi, Teju, Wunmi, Halimat, Desola, Kanyin, Ganiyat, Bukunmi, Dipson, Kunle, Kolade, A.K, iv and all other important people that I cannot remember for one reason or another. I pray God bless you all, till we meet again. Lastly, I appreciate everyone whom no matter how small, has contributed to my reputable success. May God remember you all in his garden of blessings. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page……………..……..………………………………………..i Certification…….……………………………………………………ii Dedication…………..……………………………………………….iii Acknowledgements….………………………………………………iv Table of Contents………….…………………………………………vi CHAPTER ONE 1.0 General Introduction………………………………………………….1 1.1. Historical Background………………………………………………..2 1.2 Socio – Linguistic Profile…………………………………………….4 1.2.1 Occupation……………………………………………………………4 1.2.2 Festival………………………………………………………………..5 vi 1.2.3 Religion……………………………………………………………….6 1.2.4 Marriage………………………………………………………………6 1.2.5 Mode of Dressing……………………………………………………..7 1.3 Genetic Classification………………………………………………...8 1.4 Scope of Study………………………………………………………..9 1.5 Organization of Study………………………………………………...9 1.6 Research Methodology……………………………………………...10 CHAPTER TWO 2.0 Introduction………………………………………………………….13 2.1 Literature Review……………………………………………………13 2.2 Basic Phonological Concepts………………………………………..14 2.3 Sound Inventory……………………………………………………..15 2.3.0 Migili Vowel Sounds………………………………………………..15 vii 2.3.1 Migili Consonant Sounds…………………………………………..17 2.3.2 Sound Distribution…………………………………………………..19 2.3.3 Distribution of Migili Vowel Sounds………………………………..19 2.3.4 Distribution of Migili Consonant Sounds…………………………...21 2.4 Tone Inventory………………………………………………………25 2.4.0 Tone Combination…………………………………………………..27 2.5 Syllable Inventory…………………………………………………...29 2.6 Basic Morphological Concepts……………………………………...31 2.7 Morphemes…………………………………………………………..32 2.8 Types of Morphemes………………………………………………..33 2.8.0 Free Morphemes…………………………………………………….34 2.8.1 Bound Morphemes…………………………………………………..36 2.9 Structural Functions of Morphemes…………………………………38 2.10 Structural Positions of Morphemes………………………………….39 viii 2.11 Syntactic Functions of Morphemes………………………………….40 2.12 Language Typologies………………………………………………..42 2.12.0 Fusion Language………………………………………………...…43 2.12.0 Agglutinating Language…………………………………………...44 2.12.1 Isolating Language………………………………………………..44 CHAPTER THREE 3.0 Introduction………………………………………………………… 45 3.1 Morphemes…………………………………………………………..45 3.2 Types of Morphemes………………………………………………..46 3.2.1 Free Morphemes…………………………………………………46 3.2.2 Bound Morphemes………………………………………………48 3.3 Functions of Morphemes………………………………………...51 3.3.1 Derivational Function of Morphemes……………………………52 ix 3.3.2 Inflectional Function of Morphemes…………………………….52 CHAPTER FOUR 4.0 Introduction………………………………………………………54 4.1 Morphological Processes………………………………………...54 4.1.1 Affixation………………………………………………………..,55 4.1.2 Borrowing………………………………………………………..57 4.1.3 Compounding…………………………………………………….58 4.1.4 Reduplication…………………………………………………….59 4.1.5 Refashioning……………………………………………………..60 CHAPTER FIVE 5.0 Introduction………………………………………………………61 5.1 Summary…………………………………………………………61 x 5.2 Observations……………………………………………………..62 5.3 Conclusion……………………………………………………….63 5.4 Recommendations..……………………………………………...64 References……………………………………………………….66 CHAPTER ONE 1.0 GENERAL INTRODUCTION Language is the universal fabric that holds every individual of a community together. An instrument, used by man for communication within his environment, without which there would be no meaningful relationship between the human world. Language can also be referred to as the medium through which ideas, thoughts, and other forms of human communication are expressed or carried out. In the metal compartment where all possible, meaningful and acceptable words are formed, there are certain rules that must be followed or certain conditions met before any word can be viewed as acceptable in any language. The branch of linguistics that studies the compatibility of such combinations and proposes the rules for their formation is called xi MORPHOLOGY. The basic concept of this branch is the morpheme, the smallest meaningful unit in grammar which may constitute a word or part of a word. Every language has its own set of morphological rules which are strictly adhered to by members of its community. Such members , (Native speakers) share a great deal of unconscious knowledge about their language which helps in the acquisition of their first language with little or no formal instructions. In connection to morphology, the Migili language has been duely investigated with a view to finding/revealing the aspects of its morphological set up. The Migili people are a tribal group found in Agyaragu local government, Lafia, Nasarawa State. The first chapter of this research centers on areas such as the historical background of the Migili people, their socio-cultural profile, occupation, religion, festival, mode of dressing, marriage, genetic classification. Several other aspects will be reviewed in the latter chapters of the project work. 1.1 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF MIGILI xii In an interview with the town chief (ZHE Migili) who is he traditional ruler and an autocrat, two major facts were revealed. One of them is the fact that the name of the language popularly known as Mijili is incorrect rather it is formally known as Migili. The second fact duely noted by him is that the Migili people are not part of the Hausa tribe as they have been mistakenly identified by many. The Migili tribe has a long history which dates back to the old Kwararafa Kingdom in Taraba State. The Kwararafa kingdom comprised of different ethnic groups such as Eggon, Algo, Idoma, and the Gomai. Each tribe took turns in occupying leadership positions of the kingdom and a heir was selected from the royal home of each ethic group. But things changed when it was time for Akuka, a Migili descendant who was next in line to ascend the throne . Akuka was plotted against hence he could not become the next leader. This sparked up a lot of negative reactions from the Migili people as well as some other tribes who viewed such an action as unjust, a way through which they were deprived because of their small population. Together with all members of the tribe, Akuka moved down to a place called xiii Ukari where they settled down for a while and later moved to Agyaragu in Lafia, Nasarawa State where they reside presently. Today, the Migili people are known as settlers in Obi, Agyaragu local government, Lafia, Nasarawa State, Nigeria. They can still be found in other places such as Minna, Abuja, Kubadha in Kaduna, Zuba e.t.c.The major population of about 18,000 people constitute about 96% of Obi Agyaragu local government area. 1.2 SOCIO – CULTURAL PROFILE The Migili language is rich in both its social and cultural aspects. Some of these aspects are their festival, religion, marriage, occupation e.t.c 1.2.1 OCCUPATION The Migili people are predominantly farmers. This occupation ranges from young to old, male and female. They produce a lot of crops but their major cash product is yam. Yams are produced for transportation to different parts of the country and they also engage in inter – village sales with their neighbours who do not produce the types of crops that they do. xiv Migili people also grow crop such as melon, beans, guinea corn, rice and millet. 1.2.2 FESTIVAL There are two major festival celebrated by the Migili. These festivals are very important aspects of their culture as they expose their heritage and ancestral endowments. First is the farming season in which every farmer within the village premises is involved. During this farming season, they move from one indigenes farm to another in large groups cultivating, clearing and planting different types of crops for one another. After this has been done, a date is set to celebrate the harvest of these crops and this leads to the second festival which is the Odu festival. The Odu festival is celebrated village – wide in Miligi. This is a period of harvesting of crops, celebration of the harvest, exchange of pleasantries and entertainment in the village square. During the festival, the Odu masquerade which represents their ancestral values is dressed in a colourful attire with which it displays great dancing steps to the amusement and applause of the villagers. xv Another festival that is celebrated in the village is the demise of an elderly indigene. This is done with a type of dance called Abeni. 1.2.3 RELIGION Before the arrival of the missionary, the Migili people were ardent traditionalists. They worshipped their ancestors some of which are Odu and Aleku. They had separate seasons at which sacrifices were made and worshipped them with dancing and entertainment. But things gradually began to change after the missionaries arrived thus most of them were converted to Christians, though a small population remain strictly traditional worshippers while some are Muslims. 1.2.4 MARRIAGE Marriage as an entity was approached from the early stages of childhood amongst the Migili people. Before the Missionary arrived, intercultural marriage was forbidden amongst them with serious consequences or punishment allotted the violation of such law. Marriage between indigenes was formally approached, by the father of the suitor, who informs the mother of the admired girl of his intention. Once an agreement has been xvi reached, the first payment is made to confirm the betrothal of the female child who continues to live with her parents until the due age has been reached. The male child (suitor) then pays his first installment of her dowry and engages in farming activities for his in-laws once every year. But today the order of things have changed and marriage within and outside the tribe is now by choice hence enhancing inter-cultural relationship. 1.2.5 MODE OF DRESSING The Migili dressing mode displays their cultural heritage, though their dressing is quite similar to that of the Hausa. Women wear short vests that expose their belly and long skirts that cover their legs, then they adorn their hands, forehead, lips and ankles with beads and bracelets. An interesting feature about their dressing is the plaiting of hair by both male and female indigenes. Though a bit of civilization has been introduced into their culture, hence influencing their dressing, a typical Migili indigene would still appear in colourful beads and bracelets. xvii 1.3 GENETIC CLASSIFICATION This is the arrangement of languages into their different categories according to their relationship with other members of their category. NIGER KORDOFANIAN NIGER CONGO Mande KORDOFANIAN Atlantic Congo Atlantic Ijoid Volta Congo Kru Kwa North Volta Congo Akpe Platoid Defoid Edoid Nupoid Benue Congo Idomoid ukumoid Igboid Cross river Bantoid Tarokoid Beremic Southern Yeskwa Ayongie Adunic Koro Alumic Hyame Ninzic West Jiju xviii East Tyap North Irigwe Koro Zuba Koro Ija Jijilic Koro-Makamei KORO MIGILI koro Lafiya Adapted from Roger Blench (2006) 1.4 SCOPE OF STUDY As earlier mentioned, the purpose of the research project is to closely and carefully examine the Migili language and hence, expose its morphological aspects. Investigation would be carried out on the various morphological processes attested by the language. Various steps, theories and methods would be used and considered in the analysis and exemplification of the morphemes and their processes. Also, an accurate compilation of the alphabet in the language has been carried out in order to justify the compilation of the data and its analysis thereof. 1.5 ORGANISATION OF THE STUDY This long essay has been divided into five different chapters, each containing certain aspect of the research work. Below is a highlight of the chapters and their contents;(i) Chapter one deals with general introduction into the background of the study, the historical background and socio – cultural profile; xix (ii) Chapter two deals with literature review on the chosen aspect of the research work; (iii) Chapter three deals with the presentation and analysis of data on the chosen work; (iv) Chapter four centers on the processes involved in the branch of study; (v) Chapter five deals with summary of the work done, observation, conclusion and recommendation of references. 1.6 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY In the execution of this research, both the informant and introspective methods/approach have been adopted for data collection. Two native speakers have been approached, hence providing the researcher with complete and accurate data from the Migili language. Also, a library/internet research has been adopted, serving as a guide on some primary aspects of the research such as, the geographical location of the language and its speakers, its genetic classification, its population size e.t.c. xx Below is a brief information about the two informants whose help was sought; Informant 1 (i) Name: Ayuba Osibi Haruna (ii) Age: 40 years old (c) Occupation: Personal assistant to the chairman, local government (iv) Aspect: Data collection (400 wordlist) Informant 2 (a) Name: Dr Ayuba Agwadu Audu (JP) (b) Age: 62 years (c) Position: Village chief (d) Aspect: Historical Background and socio-cultural profile. The Ibadan four hundred (400) wordlist served as the basis for data analysis. In it comprises a list of words in English language for which xxi equivalent meaning has been substituted in Migili language. A frame technique has also been used in order to find out the use of words in into sentence context. A series of sentences have also been translated from English language Migili. xxii CHAPTER TWO 2.0 INTRODUCTION The body of this entire chapter deals with literature review on the phonological and morphological aspects of the Migili language. Although the essay should be centered on the morphological aspect, there is need to examine the phonology as well, the reason being that the language (Migili) does not have a known written form, hence the need to get acquainted to it by taking a phonological approach. The second part of this chapter will revolve around the morphological aspect. This goes a long way in providing an in-depth study of the word structure and word combination processes of the study language. 2.1 LITERATURE REVIEW It is important to examine some earlier linguistic enquiries that have been made in the Migili language. This is because the earlier works that have been done on the phonological and morphological aspects of the xxiii language may not be well documented and that is the major aim of this chapter. According to Stoffberg (1978: b), the Migili language has Nine (9) phonemic vowels, seven (7) nasal vowels and twenty eight (28) consonants. He further explained that MigiIi also has three major register tones and numerous complex glide tones. The realization of morphemes in Migili language is based on different forms of phonological alternations. These alternations are either by prefixation, suffixation or tone change. 2.2 BASIC PHONOLOGICAL CONCEPTS Phonology is only concerned with the study of sounds (vowels and consonants) of a language. It is also the study of the systematic use of sounds to portray the orthography of a language. Phonology is the sub-class of linguistics that deals with the sound system of languages.Whereas phonetics is concerned with the physical production of sounds, acoustic xxiv transmission and perception of sounds, phonology simply describes the way that sounds function within a given language or across languages. 2.3 SOUND INVENTORY This deals with the classification of the sounds in a language. Migili uses a combination of both vowel and consonant sounds. 2.3.0 MIGILI VOWEL SOUNDS Vowels are sounds that are produced without any form of obstruction of air or stress in the vocal cards. There is always a free flow of air through the vocal cords in vowel production. There are four parameters used in describing vowel sounds. They include; (i) Position of the soft palate, (ii) Shape of the lips, (iii) Raising of the tongue, xxv (iv) Tongue height. There are nine (9) phonemic vowels and seven nasal vowels in Migili language. The oral vowels are; i, e, ɛ, ∂, a, ↄ, o, ʊ , u. The nasal vowels are; ĩ, ẽ, ɛ,̃ ã, ↄ̃, õ, ũ. 2.3.0. (a) Diagram Showing Migili Oral vowels. Front Central Back I high Mid high Mid low Low ʊ e o ɛ ∂ ↄ o a xxvi u 2.3.0 (b) Chart Showing Migili Nasal Vowels Front Back ʊ̃ ĩ high Mid high Mid low Low 2.3.1 Central ẽ õ ɛ̃ o ↄ̃ a CONSONANT SOUNDS According to Yusuf (1992: 13) “ Consonant sounds are produced with the obstruction of airflow, partially or totally at some point”. In phonetic terms, most consonants are sounds in whose production, the airflow is obstructed or clogged at some point in the mouth, throat or larynx, at least sufficiently to cause audible friction. In relation to the definition given, the Migili language has been found to have twenty eight consonants. The chart below will give a description of those consonants. xxvii Bilabia Plosive p Nasal Labio dental Alveolar b t d m Fricative Alveo Palatal Velar Labio Palatal Velar c n f Affricate v ~ s z ts dz Approxim ant j k g kp gb ŋ h ϊ Vibrant L Stoffberg (1978b: 67) notes an example of the contrast between long and short /l/ ; /lí/ “ to sell “ /llí/ “wart hog” Also there are instances of free variation between some of the consonants; /l/ and /r/ /l/ and /n/ /s/ and /S/ xxviii ŋm ∫ ʒ y Lateral Glottal w /z/ and /З/ 2.3.2 SOUND DISTRIBUTION Sound distribution studies how sounds are combined and distributed in a language to make meaningful words. Any sound can occur in any position either initial, medial or final depending on the type of combination processes which the language permits. 2.3.3 DISTRIBUTION OF MIGILI VOWEL SOUNDS According to research, all Migili oral vowels can occur in either word initial, medial or final positions. Here are a few examples to illustrate further; /i/ word initial- [íbe] ‘spear’ medial- [dzidzi] ‘bad’ final - [álí] ‘forest’ /u/ word initial-[ùva] ‘dog’ xxix medial-[dzárunↄ] ‘bird’ final-[dumu] ‘he goat’ /e/ word initial-[èjε] ‘no’ medial-[í∫énέrέ] ‘cloud’ final-[íswîle] ‘plaiting of hair’ /o/ word initial-[oji] ‘thief’ medial-[kokà] ‘masquerade’ final-[mónãso] ‘bush meat’ /ε/ word initial-[Èhε̃] ‘satisfaction’ medial-[ipεgã] ‘knowledge’ final-[drε] ‘to be sitting’ / ↄ/ word initial-[ↄ̀kpa] ‘antelope’ medial-[∫ↄ̀nla] ‘sleep’ xxx final-[dząrùnↄ] ‘bird’ / a/ word initial-[ásò] ‘bush’ medial-[tàsò] ‘untie’ final-[ↄ̀kpa ] ‘antelope’ 2.3.4 DISTRIBUTION OF MIGILI CONSONANT SOUND Here are some examples of the distribution of Migili consonant sounds. /b/ word initial-[bέnε] ’to pull’ medial-[íbà] ‘fish’ /c/ word initial-[cε] ‘worship’ medial-[ácansòlò] ‘finger nail’ /d/ word initial-[drí] ‘to shake’ xxxi medial-[kudunu] ’rubbish heap’ /f/ word initial-[flↄ̀] ‘wet’ medial-[kùfrↄ] ‘bark of tree’ /g/ initial-[gↄ̀] ‘catch’ medial-[áglo] ‘sorghum’ /gb/ initial-[gbètúmá] ‘messenger’ medial-[kúgbã] ‘thatch roof’ /h/ initial-[hár] ‘until’ medial-[Èhε] ‘satisfaction’ /k/ initial-[kúcↄ̀ ] ‘head’ xxxii medial-[kúkũ] ‘bend down’ /kp/ medial-[ìkúkplá] ‘strength’ /l/ initial-[lí] ‘to sell’ media-[múlá ] ‘bitterness’ /m/ initial-[mɛ̀rε] ‘to learn’ media-[gbètúma] ‘messenger’ final-[ mbãm] ‘palm wine’ /n/ initial-[ńla] ‘sleep’ medial-[nònó] ‘become fat’ final-[má nyran] ‘marry wife’ /s/ xxxiii initial-[sεrε] ‘deny’ medial-[tàsↄ̀] ‘untie’ /∫/ initial-[∫ↄ̀kↄ̀pá ] ‘rice’ medial-[gú∫o] ‘stool’ /t/ initial-[ta] ‘chew’ medial-[kíta] ‘skin’ /ts/ initial-[tsi] ‘harvest’ medial-[itsi] ‘nest’ /w/ initial-[wusↄ] ‘listen’ medial-[juwↄ] ‘hold’ /dz/ initial-[dzárunↄ] ‘bird’ medial-[adzá] ‘children’ xxxiv 2.4 TONE INVENTORY Tone is referred to as the use of pitch in language to distinguish between lexical and grammatical meaning i.e, to inflect words. All verbal languages use pitch to express emotional, ideological or other human features. Migili is a tonal language and it uses the three major types of tone extensively. The high tone is represented with a rising slant line (/), the low tone is represented with a falling slant line (\), while the mid tone is usually not marked in words. The Migili language also uses complex glide tones such as low-high (v), high low (^) e t c. there are a few examples below to illustrate better; (1) HIGH TONE form gloss bέ ‘to come’ ká ‘that he’ kέ ‘to deny’ xxxv (2) (3) (4) LOW TONE form gloss bÈ ‘to choose’ kà ‘to exceed’ nì ‘to bury’ MID TONE bε ‘question participle’ ka ‘to guard’ nↄ ‘to write’ LOW-HIGH bě kă (5) ‘two’ ‘like’ HIGH-LOW form gloss kpô ‘grow tall’ kpî ‘be short’ xxxvi 2.4.0 TONE COMBINATION Words can naturally possess the three major types of tone. This could be the high, mid, or low tone. These three tones can be combined using mono-syllabic, Di-syllabic or Poly-syllabic words. The complex combination of these tones also gives an output known as contour tones. A few examples of Migili tone combination are given below; (1) (2) (3) HIGH-HIGH ásá ‘sorghum’ áwá ‘fear’ HIGH-LOW ásò ‘bush’ ísà ‘day’ LOW-LOW dùmù ‘goat’ jìjì ‘to tickle’ xxxvii (4) (5) (6) LOW-HIGH lìyí ‘price’ nìmí ‘orange’ HIGH-LOW-MID dzárùnↄ ‘bird’ ínùma ‘hunger’ LOW-HIGH-HIGH rùpéné ‘pig’ gbètúmá ‘messenger’ The three major tones can be combined in several ways in any given language. xxxviii 2.5 SYLLABLE INVENTORY Hyman (1975:189) defines syllable as “a peak of prominence which is usually associated with the occurrence of one vowel or syllabic sonorant”. He further explained that a closed syllable ends with a consonant while an open syllable ends with a vowel. Migili language exhibits a high number of open syllables but a fair number of closed syllables. The reason is that, only the syllabic consonant /n/ and /m/ are allowed to end words/occur in word final position thus limiting the number or use of closed syllables in the language. Below are examples of mono-syllabic, Di-syllabic and Poly-syllabic words in Migili language. (i) Mono-syllabic words [bɛ̀] ‘choose’ cv [cε] c v ‘worship’ [gↄ] ‘catch’ CV xxxix (ii) Di-syllabic words [m̀/bãm] ‘palm wine’ c cvc [gù/so] ‘close’ cv cv [kí/dʒì] ‘feather’ cv cv [n/sí] ’tear’ c cv (iii) Poly-syllabic words [∫ↄ/kↄ/pa] ‘Rice ’ cv cv cv [Kↄ̀/ró/kↄ̀] ‘Cock’ cv cv cv [ á/va/m/bu] ‘harmattan’ v cv c cv [n/nↄ/sↄ/nↄ] c cv cv cv xl 2.6 BASIC MORPHOLOGY CONCEPTS Morphology according to crystal (1990:225) is the branch of linguistics which studies the structure or forms of words primarily through the use of morphemes. Lyons (1971:180-181) “Morphology is the study of forms, the field of linguistics which studies word structure and word formation”. The term morphology was Introduced into the area of language in the 19th century by a scholar called Geothe. The term was first applied by Geothe to biology as the study of ‘forms’ of living things. The Morpheme is the basic concept of the term morphology. Morphemes are the minimal unit of grammar, the unit of lower rank, out of which words, the unit of a higher rank are composed (Lyons 1974:81). According to Spencer (1991), “the domain of morphology in its study encompases the possible arrangement of morphemes to form words”. He further explains it as the relationship or reactions of several morphemes in the process of word formation.This can be Illustrate thus; xli Morphemes Morphology Arrangement 2.7 MORPHEMES Nida (1946:6) defines morphemes as “the minimal meaningful unit of which a language is composed and may be part of a word or constitute a word independently”. Equally in the tradition of American structural linguistics established by Leonard Bloomfield (1993), “a Morpheme is smallest unit of a language with meaning.” Yusuf (1987; 1988) described morphemes as building blocks of words in any language. He defines morphemes as the minimal meaningful unit of grammatical analysis. From the definition above, we can deduce that morphemes are characterized by certain features. First, a morpheme is seen as the smallest broken down unit of grammar which makes meaning. Here are some examples of morphemes selected from different languages. xlii 2.8 word gloss language Orí lead Yoruba ilé house Yoruba dàru finish kahugu Òyi thief Igala Múna meat Migili dùmù goat Migili kↄ̀rↄ́kↄ̀ cock Migili TYPES OF MORPHEMES There are basically two types of morphemes. These are the free and bound Morphemes .The distinction between both types of morphemes is basically their nature and composition, structural position and structural functions. Lexical Free Morphemes Functional Bound Derivational Inflectional xliii 2.8.0 FREE MORPHEMES Oyebade (1992:58) defines a free morpheme as “a morphological unit which can exist in isolation”. It is a unit which is capable of standing or existing on its own without being attached to any other linguistic unit. It is independent in terms of meaning and form. Free morphemes can occur as complete words; they are potential words (Collinge 1990). Let us consider the following examples of free morphemes in Migili language. Word Gloss ágîtã food bɛ̌ two ítuma vagina kíci tree kíta skin kísí eye dzá child xliv gwàra open ígaba Lion jì sting múna flesh Each of the examples consist of only one morpheme that cannot be further broken down or subdivided into any meaningful parts. Each has independent existence and meaning. Free morphemes fall into two categories; (i) The lexical category, (ii) The functional category. The lexical category consists of the set of ordinary nouns, adjectives, and verbs which carry the content or message in sentences. The lexical morphemes (open class of words), are content words such as nouns, verbs and objectives. They belong to the open class because we add new lexical morphemes or affixes to them. The other group of morphemes is called the functional morphemes. This set consists of mainly functional grammatical words in the language xlv such as conjunctions, prepositions, articles and pronouns. They are described as the closed class of words because we do not add any functional morphemes or affixes to them. Here are a few examples; 2.8.1 Words Gloss ímε I (singular) íwↄ you (singular) íla we (plural) ìyi they (plural) BOUND MORPHEMES Unlike free morphemes, bound morphemes cannot stand independently. A bound morpheme is a type of morpheme that cannot occur in isolation but can only be recognized when they are attached to other bound or free morphemes (Oyebade, 1992:59). Bound morphemes do not constitute independent words, hence they are called affixed. Affixes could be inflectional or derivational in nature and are of three different types; Prefixes, Suffixes and Infixes. xlvi Prefixes are attached to words at the initial positions, suffixes are added at word final positions while infixes are attached in the word medial positions. Examples of affixes in English language include; + s → Books (ii) sheep + s → sheep (iii) mis + lead (iv) Dis + qualify + ed → disqualified (i) Book → mislead Examples of affixes in Migili language include; (i) á (ii) (iii) (iv) ‘child’ Dzá ‘children’ + dzá kúpele ‘stone’ á + pele ‘stones’ dzárùnↄ ‘bird’ a + dzárunↄ ‘birds’ Gbolu ‘Elephant’ i + ‘Elephants’ gbolu xlvii (v) ‘bone’ kuku a + ‘bones’ kú The most commonly use form of affix in Migili language is the Prefix. 2.9 STRUCTURAL FUNCTIONS OF MORPHEMES Morphemes perform certain roles in the process of word formation. Free morphemes perform the function of roots to which other free or bound morphemes are attached. For example, the word ‘International’, has a root word, ‘nation’. Some bound morphemes function as a form of negation while others may function as agentive markers, changing the syntactic class of a word. e.g engage → disengage → disengagement. It is possible to have more than one root in a word. For instance, the word “milkmaids” has the morphemes, ‘milk’ and ‘maid’ to which the plural marker ‘s’ is added. The function of the root is not exclusive to free morphemes alone as we may have a bound morphemes sometimes combining with free morphemes to form new words. xlviii 2.10 STRUCTURAL POSITION OF MORPHEMES In the process of morpheme combination, It is important to determine/acknowledge the positions of such combinable morphemes. Those which are added before, in between, or after a root are called affixes. An affix may occupy the structural position of a prefix in which case, it occurs before the root word. It can also occupy the position of an infix, occurring in between a word. An affix may also function as a suffix when it occurs after the root word (Bloomfield 1933). Let us consider example from English language: (A) (i) iL + legal (ii) Dis + courage (iii) mis + understand iL-, Dis- and mis- are all prefixes. (B) (i) Good + ness (ii) Region + al (iii) correct + ion -ness, - al, - ion are all suffixes. xlix 2.11 SYNTANTIC FUNCTIONS OF MORPHEMES A morpheme may perform a derivational or inflectional function. Morphemes performing derivational functions usually change the syntactic class of a word. For example; Verb Noun Ride Rider Teach Teacher Rape Rapist Noun Adjective Boy Boy - ish Affection Affection - ate Passion Passion -ate A derivational function may also be assumed by prefixes. This can be observed using examples in Yoruba language; Verb Noun Ró ‘ to sound’ ìró ‘ a sound’ Gé ‘ to cut’ ègé ‘ a segement’ Dé ‘to wear’ adé ‘a crown’ l Migili morphemes also perform derivational functions through the use of suprafix. A suprfix is a types of affixation that is represented by prosodic features such as tone, stress, intonation e.t.c. some examples are; Word Gloss ŃLa ‘sleep’ ŃLá ‘difficulty’ ní ‘to extinquish’ ‘to bury’ nì Morphemes which perform an inflectional function only provide more syntactic information without changing the class of a word. Some examples are given in Migili below; (i) á + béré = pl + partner = (ii) á + dzá pl + (iii) ì + partner partners = ádzá child = children gbolu = lgbolu li pl 2.12 + Elephant = Elephants LANGUAGE TYPOLOGIES Languages are systematically grouped into structural components based on phonology, grammar or vocabulary, rather than in terms of any real or assumed historical relationship (crystal, 1987). The earliest typologies however were based on morphology. (crystal 1987:293) recognized three main linguistic types based on the way a language constructs its words. They are; 1. 2.12.0 Fusion 2. Agglutinative 3. Isolating FUSION LANGUAGE Also known as inflecting or synthetic language, a fusion language is one in which a word is made up of two or more morpheme that are not easily recognizable. Fusion languages show grammatical relation by changing the lii internal structure of words, using inflectional ending which express several grammatical meanings at once. Examples of such languages are Latin and Greek. 2.12.1 AGGLUTINATING LANGUAGE In an agglutinating language, words are built up of a sequence of units, with each unit expressing a particular grammatical meaning in a clear one to one way (crystal 1987:294). languages that attest this type of feature can have a single word being built up by man morphemes which can be easily separated into the meaning which each district morpheme expresses. Examples are English and Turkish. 2.12.2 ISOLATING LANGUAGE In a predominantly insolating language, each word is made up of one morpheme which cannot be further broken down. Grammatical relationships are shown through the use of word order. In this type of language, there are inflections, i.e one word, one meaning. In Chinese for example, verbs are not inflective for persons, number or tense neither are nouns inflected for liii number or gender. It is therefore difficult if not impossible to find prefixes or suffixes in an isolating language. Based on the language typologies that have been identified above, one can therefore highlight the fact that Migili is both a fusion and agglutinating language. liv CHAPTER THREE 3.0 INTRODUCTION According to crystal, (1990:225), “morphology is the branch of linguistics which studies the structure or forms of words primarily through the use of morphemes”. The morpheme is the basic concept of the study of rules guiding word formation. The basic aim of this chapter is to discuss more intimately, the morphemes, its type and its functions. This will be done using the Migili language in the following phases of the chapter. 3.1 MORPHEMES Lyons (1994:81) defines morphemes as the minimal unit of grammatical analysis, the units of lowest rank, out of which words, units of higher ranks are composed. Also, Oyebade (1992:82) defines the morphemes as the “minimal meaningful unit of grammatical analysis, which may constitute a word or part of a word”. Here are a few examples of morphemes in Migili; Nimi ‘orange’ pa ‘hit’ lv 3.2 Ra ‘play’ trↄ́ ‘cook’ tútrↄ ‘laugh’ TYPES OF MORPHEMES Morphemes can be divided into two major types, these are the free morphemes and the bound morphemes. 3.2.1 FREE MORPHEMES Oyebade (1992:58) defines a free morpheme as a “morphological unit which can exist in isolation”. It is also known as the root of a word. A free morphene is independent both in meaning and from. It cannot be subdivided into further meaningful parts. Free morphemes fall into the categories, these are the lexical and functional morphemes (Hudson, 2000). The first category consists of ordinary nouns, adjectives and verbs, the category of words referred to as content words. lvi Examples of these lexical morphemes in Migili language are: Words Meaning áklodzi money ásò bush bé came drí shake dzidzi bad nɛ̀nɛ̀ sweet The group of free morphemes is called functional morphemes function in the language such as conjunctions, prepositions, articles and pronouns. We do not add new functional morphemes to this class of words hence they are described as the “close class of words”. Here are a few examples in Migili language. lvii Words Meaning ìmɛ̀ I ìnↄ He inↄ Him la We ba They The set of words given as examples in both categories are indivisible. They posses individual meaning and can also act as root forms for the addition of other morphemes to produce new words. 3.2.2 BOUND MORPHEMES A bound morpheme according to Yusuf (1992:83), “is a type of morpheme which does not occur in isolation but can only be recognized when added to other free or bound morphemes”. These morphemes have definite meaning but do not have independent existence. Bound morphemes are basically or three types: lviii (i) Bound morphemes that occur before the root morphemes. These are called prefixes. (ii) Bound morphemes that occur within the root morphemes. These are infixes. (iii) Bound morphemes that occur after the root morphemes. These are suffixes. These three types of bound morphemes are called affixes because they are attached as minor appendage to their partners as a way of modifying or adjusting the systematic content of the free morphemes. Example of bound morphemes in Migili language are the plural formation prefixes [a-], [i-], [m-] and [n-] which occur before root words. The prefixes [a-] and [i-] occur/appear before velars and labials. Here are a few examples showing the outlined prefixes; (i) [a-] word meaning plural dzá child ádzá gbé hunterágbé lix kídrî housefly ádrî kisi aye álí word meaning plural dùmù goat ídùmù ↄjέ witch ìjέ odↄ́ horse ìdↄ́ uνa dog ìva gbolu Elephant igbolu word meaning plural [l-] [m-] [n-] Ninyira wife míninyira ńnyɛ person mínyε òca uncle múca shá husband múshá word meaning plural lúkↄ́ war ńkↄ́ lúnwↄ̀ voice nwↄ́ lx rúgↄ̀ mountain ńgↄ̀ SUFFIXES Very few cases of suffixation occur in Migili language nevertheless, some example of suffixes are found below; word 3.3 meaning plural gbo fall gbєrє gu wash gùgra FUNCTION OF MORPHEMES Morphemes combine to form words. Root morphemes are the base from which other words are derived. The root morphemes function as the stem when other morphemes are added to it (Oyebade,1992). Thus a root morpheme can be a stem and a stem can be a root. Nida (1946:99) state that a morphemes can perform the following synthetic functions: (i) Derivational function, lxi (ii) Inflectional function. 3.3.1 DERIVATIONAL FUNCTION A morpheme performing a derivational function usually changes the syntactic class of the lexical item to which it is attached. Thus, when morphemes are combined and a new meaning is derived, the attached morpheme has performed a derivational function. Miligi morphemes do not perform derivational functions. 3.3.2 INFLECTIONAL FUNCTION Oyebade (1992:88) state inflectional morphemes only provide more syntactic information without changing the word class. This function of morphemes gives additional information to the meaning of the root words. Number, tense and gender are some of the inflectional functions of morphemes. Examples of morphemes performing inflectional functions in Migili language are given below: lxii Singular Gloss Plural Gloss Dzá child ádzá children Dzárúnↄ bird adzárúnↄ birds gbέ hunter ágbέ hunters gbolu εlephant igbolu εlephants kígì feather ájì feathers kínyí tooth ányí teeth kílí rope álí ropes kísí εye ásí eyes kítátrè shoe átátrè shoes lúnwo voice nwό voice mùkↄ̃ corpse ìkↄ̃ corpses múnasↄ̃ animal ínasↄ̃ animals músù cat ámúsù cats όcã uncle múcã uncles oyi thief áyi thieves lxiii CHAPTER FOUR 4.0 INTRODUCTION In this chapter is a presentation and analysis of the basic morphological processes that exist in Migili language. The analysis will review these morphological processes with copious data from the Migili language. 4.1 MORPHOLOGICAL PROCESSES Morphological processes, otherwise known as word formation processes are ways or methods through which words are formed in a language (Quirk, et.al, 1972. Odebunmi, 2001). These processes include; compounding, blending, clipping, reduplication, acronym, coinage/announce formation, back formation, neologism and borrowing. Although not all these morphological processes are attested in Migili language, the major ones which were discovered would be discussed as follows: lxiv 4.1.1 AFFIXATION This is a morphological process by which bound morphemes are added before within or after root /free morphemes. In other words, it is the process of word formation either by prefixation, infixation or suffixation (Bloomifield, 1993).Through this processes, lexical and grammatical information is added to the sense of the root. An affix can be made up of a letter, two, three or more, depending on the structure of the language. The most common types of affixes are the prefix and suffix , while the most common in Migili are the prefixes. Examples of affixes in Migili are given below; PREFIXES a + Lémù = ‘pl’ = oranges orange alémú a + dzá = ádzá ‘pl’ = children í child + dùmù = ídùmù lxv ‘pl’ I goat = goats + gbolu = igbolu ‘pl’ Elephant = Elephants n + lunwò = nwò ‘pl’ voice = voice mú + mrú = múmrú ‘pl’ mother mothers ń + rúgõ = ńgõ ‘pl’ = mountains mountain mú + shá = múshá ‘pl’ = husbands husband SUFFIXES Gb + rε = gbεrε fall + pl = falls lxvi 4.1.2 Gu + rε = gùgra wash + pl =washes BORROWING This morphological process involves taking lexical items from one language and introducing it into another. Borrowing can be defined as the introduction of single words or short idiomatic phrases from one language into another (Gumperz, 1984). Borrowed words are known as loan words which undergo changes in order to adapt to the phonological structure of the borrower language. Like several other languages, Migili also borrows from neighbouring languages. These include; borrowed word source language gloss Lѐmu Hausa orange Marakanta Hausa (makaranta) school gwãgwa Hausa head pad kidíga Hausa (bindiga) gun Iↄ́hↄ̀ Hausa water leaf lxvii 4.1.3 Baga Nupe (bagadozhi) salutation sàprû Hausa (salubu) soap shↄkↄpa Hausa (shinkafa) rice Lafía Arabic peace COMPOUNDING Compounding involves the combination of two or more free morphemes. According to Oyebade (1992:62), compounding is the putting together of different lexical items to form new words. examples of this in Migili language are given below: Word Combination Output Yam + flour = Yamflour ntre = fùléntrí dro + kasha = drokishisha tell = storyteller grave + yard = graveyard ízan = itsizan black + board = blackboard titre + kúpi = kúpitítre fùlé story itsi lxviii 4.1.4 REDUPLICATION Reduplication is the process of repetition of a word or a part of a word in order to generate a new word or meaning. Reduplicatives are forms which are either partially or fully copied from the root and added before or after the root (Olaoye 2002:77). Yusuf (1992:86) defines reduplication as a process that involves copying the whole or part of a root as prefix or suffix. There are two types of reduplication; Total Reduplication: This process involves copying the whole word from the root. Examples In Migili are : word Reduplicated form Klↄ klↄklↄ ‘big strong flo floflo slow slowly Partial reduplication: This process involves copying a part of the root word and repeating it either as a prefix or suffix. Examples are; word Reduplication form Quick Quickly lxix 4.1.5 pla papla swim float srwě srwisrwě day daily ísà ísàsà REFASHONING In refashioning, a phrase or a word is named by its description. Examples in Migili language; /Kpàtì/ + Box /kpàtì/ box /tere/ = /kpàtìmatere/ talk + = radio mázá = kpàtìmázá image = television lxx CHAPTER FIVE 5.0 INTRODUCTION This chapter gives the summary and conclusion of previous ones. It also includes observations and recommendations based on the researchers findings. 5.1 SUMMARY This study started with an introductory chapter that gives information about the language of study (Migili), investigating the historical background of the language, the speakers origin and settlement, their genetic classification, socio-cultural profile, scope and organization of study, data collection and data analysis. In this essay, an attempt has been made to look into the morphology (study of word formation rules) in Migili language. The work started by giving definition of the term morphology, the concept of morphemes and how they combine in the language to form new words. The work comprehensively looks into the morpheme, its type and functions. lxxi The combination of morphemes as seen in this long essay, is mediated by the morphological processes which includes affixation, borrowing, reduplication, compounding and refashioning. The work also covered some aspect of the Migili phonology looking into the sound inventory, tone inventory and syllable structure of the language. Finally, a detailed work was carried out on the morphological processes in the Migili language using Migili examples. 5.2 OBSERVATIONS At the end of the research, the following observations were made and registered on word formation in Migili language: (a) It was observed that the language has more free morphemes than bound morphemes, (b) (c) That bound morphemes perform only inflectional functions, Prefixes and suffixes are present in the language but are only used to mark plural cases or as plural markers, lxxii (d) It was also discovered that the language sometimes uses the same orthography form to represent words with entirely different meanings. example: drò → hare and drò → speak. 5.3 CONCLUSION The focus of this study is to describe the word formation processes in Migili language. We have achieved this through ample and copious data to illustrate how each of these processes is attested in Migili language. This also proves the fact that the morphological processes of affixation, compounding, borrowing, reduplication and refashioning are quiet present (though minimal) in the language. In this essay, twenty eight consonants, nine oral vowels and seven nasal vowels were discovered. Conclusively as part of contrition to learning, this long essay would be a useful guideline and reference book for future researchers, textbook writers and teachers of Migili language. lxxiii 5.4 RECOMMENDATIONS The researcher presents the following recommendations upon completing this research work; (a) Parents need to speak and teach their children the native language so that they can achieve competence in their mother-tongue before they encounter a second language, (b) The national language policy should recognize Migili language as a subject to be taught in areas largely populated by the Migili people, (c) Native speakers of Migili language should be trained as teachers of the language to encourage its development, (d) Linguists should make adequate research work on Migili language so as to make materials such as dictionaries and textbooks available for students, teachers and other researchers to learn more about the language, (e) The government should make mother-tongue teachers available in schools. Provisions should also be made for some subjects to be taught in the lxxiv mother tongue of some regions as this will give students solid foundation on the knowledge of their mother tongues. lxxv REFERENCES Andrew, S (1991) Morphological Theory. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Publishers Ltd. Bamgbose, A (1963). A Study of the Structure and Word Classes in the Grammar of Modern Yoruba. P.H.D Thesis, Eidingburg. Bloomfield, L (1933) Language. New York, Henny Holds and co Collin N.E (ed.) (1990). An Encyclopedia of language. London and New York: Rutledge. Crystal, D (1990). A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. London, Blackwell. Crystal, D (1987). The Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Douglas, p (1987). The Worlds Major Languages. London British Library Cataloguing. Eka, D (1994). Element of Grammar and Mechanics of the English Language. Oyo: Samuf (nig) ltd. lxxvi George, Y (1985) The Study of Language. Louisiana, Cambridge University Press. Greenberg J. h and Spencer J (1967) West African language Monograph Services. Cambridge University Press. Gumperz, J (1984). Discourse Strategies: Studies in International Sociol Linguistics. London, Cambridge University Press. Hyman, L (1975) Phonology: Theory and Analysis, New York Holt, Rinehart and Winston. Lyons, J (1968) Introduction to Theoretical Linguistics. London: Cambridge University Press. Matthews, P.H (1974) Morphology: An Introduction to the Theory of Work Structure. Cambridge, C.V. P. Nida, E (1949) Morphology: The Description Analysis of Words. Ann Arbor, The University of Michigan Press. Oyebade, F. O (1992) : Morphology in Yusuf O. (ED) lxxvii Siegel, D (1979). Topics in English Morphology. New York Garland. Yusuf, O and F. Oyebade (1989): Basic Grammar: Phonology, Morphology and Syntax. University of Ilorin M. S. lxxviii lxxix