Supplemental Reading Materials

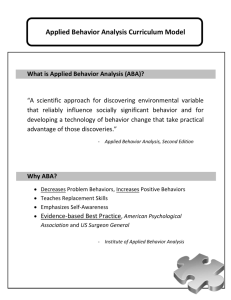

advertisement