Craniosynostosis vs Positional Plagiocephaly

advertisement

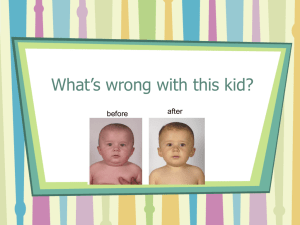

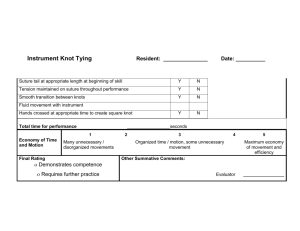

What’s Wrong With My Baby’s Head? Cathy Cartwright, RN, MSN, PCNS Pediatric Clinical Nurse Specialist Neurosurgery c2cartwright@gmail.com Plagiocephaly – asymmetry and twisted condition of the head Greek (plagios –oblique + kephalē – head) History of Deforming the Head Artificial deformation of the neonatal skull A way to differentiate from others (like tattoos, body piercing) Known since 4000 BC in ancient Phoenicia Mechanisms Compressing front and back of head with board and pads Cradle-board Tightly wrapping the head with a binding Most craniosynostosis is recognizable at birth Some molding of the skull during birth process, but usually normalizes by 3 weeks of age Craniosynostosis – premature closure of one or more cranial sutures Nonsyndromic – most common Over 90 syndromes Partial closure of one suture can cause a deformity Important to recognize craniosynostosis or positional molding early so appropriate intervention can take place Causes Genetic conditions (mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptors) Metabolic disorders - hyperthyroidism Hematologic disorders Overshunting hydrocephalus (secondary craniosynostosis) In utero head restraint – multiple births, maternal smoking, valproate Etiology Brain is contained in neurocranium which is comprised of skull base and cranial vault Sutures allow infants head to reshape during and after birth process and to accommodate rapidly expanding brain Removing skull in neonate with intact dura results in the dura regenerating the skull with suture placed as dictated by the dura Bone growth occurs from the expanding brain Skull is 35% adult size at birth and 90% adult size by 7 yrs Nonsyndromic Craniosynostosis 1 out of 2100 children Multiple suture synostoses involving 2 or more cranial sutures occur in 4-8% of nonsyndromic craniosynostosis Simple craniosynostosis is usually random in occurrence but 2-6% of isolated sagittal synostosis and 8-14% of coronal synostosis were found to be familial In utero head restraint also thought to be a cause but is most commonly seen as positional plagiocephaly Sagittal Synostosis – most common Called scaphocephaly (boatlike shape to skull) 40-60% of all craniosynostosis Bitemporal narrowing, frontal bossing, occipital cupping, palpable sagittal ridge CT - Closed sagittal suture with ridge Lateral skull x-ray Coronal Synostosis Anterior plagiocephaly 20-30% of all craniosynostosis Vertical dystopia, nasional deviation, flattening of frontal bone on affected side Strabismus from ipsilateral superior oblique paresis and compensatory contralateral head tilt present in 50-65% of unilateral coronal synostosis See ophthalmologist familiar with craniosynostosis AP skull film shows harlequin appearance to orbit as superior orbital rim is elongated CT - closed L coronal suture AP skull x-ray - Harlequin sign (L) Metopic Synostosis Trigonocephaly Involves metopic suture 10% of all craniosynostosis Triangular shape Bitemporal narrowing Parietal bossing Hypotelorism Metopic ridge Can have normal skull shape and just a ridge (fussy?) Lambdoid Synostosis Occipital (or posterior) plagiocephaly Involves lambdoid suture 1-2% of all craniosynostosis Trapezoid shape to skull when viewed from above Tilted skull base (affected side displaced inferiorly Affected ear displaced inferiorly and posteriorly Palpable ridge along suture line Occipitomastoid bulge Towne’s View skull x-ray Classifications of Craniosynostosis Type of Craniosynostosis Scaphocephaly (dolicocephaly) Suture Involved Sagittal Incidence 40-60% Characteristics Bitemporal narrowing Frontal bossing Occipital cupping Palpable sagittal ridge Anterior plagiocephaly Coronal 20-30% Vertical dystopia Nasional deviation Flattening of frontal bone on affected side Trigonocephaly Metopic 10% Triangular shape Bitemporal narrowing Parietal bossing Hypotelorism Metopic ridge Posterior plagiocephaly Lambdoid 1-2% Trapezoid shape Tilted skull base Occipitomastoid bulge Important to differentiate between lambdoid synostosis (treatment is surgery) and positional plagiocephaly (usually no surgery). Lambdoid Synostosis Positional Plagiocephaly Usually present at birth Usually not present at birth Trapezoid shape when viewed from above Parallelogram shape when viewed from above Ipsilateral ear displaced posteriorly and inferiorly Ipsilateral ear displaced anteriorly Bony ridge palpable over closed lambdoid suture No bony ridge over lambdoid suture Unilateral occipito-parietal flattening posteriorly Usually unilateral occipito-parietal flattening but can be bilateral When viewed posteriorly there is an ipsilateral occipitomastoid bulge and the skull base appears tilted When viewed posteriorly the skull base is horizontal and no occipitomastoid bulge Radiographic evidence of closed suture (Towne’s view, CT with bone windows, CT with 3D recon) Radiographic evidence of open sutures May have torticollis Positional Plagiocephaly Deformational forces such as the birth process, can shape the skull Infant brain grows rapidly during first several months after birth This growth expands the skull into its normal shape H.C. is 35 cm at birth and increases 9 cm by 6 mo and 12 total by 1 year – 2 ¼ cm from age 1 -2 yrs and ¾ cm from age 2-3 yrs Deformational forces can have a significant impact during the period of rapid skull growth (infant seat, car seat, mattress, swing, stroller) 2 mo – 700 hours sleeping - Frequently noticed by pediatrician at 2 mo exam (normal at birth) Head must be rotated to redistribute the forces of gravity Further aggrevated by torticollis - tightening of sternocleidomastoid or cervical muscles that prevent the infant from turning his head 180 degrees Significant increase in positional plagiocephaly since 1992 when the American Academy of Pediatrics initiated the back to sleep campaign and recommended that infants sleep on their backs or sides to decrease the incidence of SIDS Parents relate that baby preferred to sleep on back with head turned to one side Can have flattening of one side or the entire occipital bone Head shaped like parallelogram Treatment for Positional Plagiocephaly Can be prevented – reposition the infant’s head when lying supine, starting from birth - doesn’t cause brain damage Toys or objects of interest placed on nonpreferential side Alternate arms when feeding Put sibling on nonpreferred side Tummy time when awake Cranial orthotic device to correct moderate to severe cases if parents have tried to reposition without success Most effective between 4 – 12 months Refer to orthotist experienced in cranial orthotic devices for positional plagiocephaly Reimbursement issues (careful with documentation – indicate that parents tried repositioning without success if true) Correct torticollis if present Static stretching exercises Confirm no C-spine defect first Slowly turn head 90 degrees toward non-preferential side, hold it for 10 sec – someone may need to hold shoulders Correct head tilt Do 5-6 times per day or with every diaper change Sternocleidomastoid tumor of infancy Syndromic Craniosynostosis Present with characteristic group of findings Multiple cranial suture synostoses including sutures of the cranial base, resulting in complex face and skull deformities Frequently associated with medical problems including hydrocephalus, papilledema, respiratory distress and failure to thrive Most common are Crouzon, Apert, Pfeiffer Crouzon Syndrome First described by French neurologist in 1912 Autosomal dominant Incidence – 1/25,000 births Caused by multiple mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2) Bicoronal synostosis (short cranium, broad, flat forehead, may have sagittal or lambdoid synostosis or even a cloverleaf deformity – Kleeblattschadel) Various degrees of exorbitism (exophthalmos, proptosis), hypertelorism and maxillary/midface hypoplasia High risk for serious ocular abnormalities (papilledema, optic atrophy, corneal exposure and proptosis) Tarsorraphy Conductive hearing loss Serious airway compromise, challenges with oral feeding (trach, GT) At risk for developing hydrocephalus and/or Chiari Apert Syndrome Acrocephalosyndactaly Type I (named after French neurologist who described the syndrome in 1906) Most complex of craniofacial syndromes Autosomal dominant Incidence 1/50,000 to 1/160,000 Mutation of FGFR2 gene Multiple suture synostosis Skulls are turricephalic (tower-like) Flat and elongated forehead, bitemporal widening and bilateral flattening of the occiput Beaked nose May have hydrocephalus and agenesis of the corpus callosum Syndactaly (fusion of digits in hands and feet) Dental abnormalities (cleft palates), conductive hearing loss, cardiac anomalies and chronic acne Mental retardation and learning disabilities are higher in this group than in Crouzon, although many can have normal intelligence Pfeiffer Syndrome Autosomal dominant Incidence of approx. 1 in 200,000 Caused by mutations in FGFR1 or FGFR2 Multiple suture synostosis, varying degrees of mental retardation, midface hypoplasia and upper airway anomalies Proptosis Broad thumbs and great toes Important for these children to be evaluated by an experienced craniofacial team Craniofacial Team Craniofacial Surgeon Neurosurgeon Orthodontist Geneticist Speech Pathologist Social Worker Audiologist Advanced Practice Nurse Pediatrician Psychologist Otolaryngologist Ophthalmologist Prosthodontist Pediatric Dentist Treatment for Craniosynostosis Surgical The American Medical Association defines cosmetic surgery as “surgery performed to reshape normal structures of the body in order to improve the patient’s appearance and self-esteem. Reconstructive surgery is performed on abnormal structures of the body, caused by congenital defects, developmental abnormalities, trauma, infection, tumors or disease. It is generally performed to improve function, but may also be done to approximate a normal appearance” Also done for cosmetic and psychological benefits Can’t wear ball caps, helmets, hard to pull shirts on over head Vertical dystopia Possible increased ICP – can lower IQ 1888 – L.C. Lane performed first craniectomy to remove a stenosed suture on a 9 mo old infant High mortality rates, anesthesia high risk, abandoned until 1927 to prevent blindness Usually not before 3 mo of age (3-12 mo is usually time to operate) Many techniques: Fronto-orbital – metopic, unicoronal, bicoronal, syndromic (usually staged procedures) with calvarial vault remodeling Pi – extended strip craniectomy Hung span – correct severe sagittal synostosis Strip craniectomy – treats sagittal synostosis, best before 6 mo of age Endoscopic strip craniectomy – all sutures, best results before 4 months of age Important to identify craniosynostosis early so pt. has more options and may undergo less invasive treatments Endoscopic strip craniectomy Developed by Jimenez and Barone in 1996 Calvarial vault remodeling – blood losses from 25% - 500% 267 patients over 8 years Decrease in blood loss/transfusions Overnight stay Molding helmet for approximately 1 year Postoperative Nursing Care frequent v.s. with neuro assessments watch for early signs of blood loss, electrolyte imbalance, neurologic deterioration or CSF leak swelling, airway problems pain control parent participation discharge and follow up care Babies with sagittal synostosis should lie with the back of the head on the mattress to decrease the AP length Long Term Outcome 286 patients from 1996-2004 Questionnaires mailed to 141 known addresses Asked parents to evaluate cosmetic, psychosocial, neurocognitive and overall satisfaction Mean follow up – 6.1 years (range 3-11 years) 100% would recommend procedure to family/friends and do it again 92% excellent school performance <5% had revision of any kind 10% teased sometimes No child reported being teased often References American Medical Association Policy of House of Delegates, June 1989, p.A-89. Definitions of “cosmetic” and “reconstructive” surgery, H-435.992. Council of Medical Services Annual Meeting. Cartwright, C.C., Jimenez, D.F., Barone, C.M., & Baker, L. (2003). Endoscopic strip craniectomy: a minimally invasive treatment for early correction of craniosynostosis. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, (35)3,130-138. Cartwright, C.C. Craniosynostosis and Positional Plagiocephaly. In Cartwright, C.C. & Wallace, D.W. (2007). Nursing Care of the Pediatric Neurosurgery Patient. Springer: Heidelberg. Jimenez, D.F. & Barone, C.M. (2010). Multiple-suture nonsyndromic craniosynostosis : early and effective management using endoscopic techniques. J Neurosurg Pediatrics, 5:223-231. Komotar, R.J., Zacharia, B.E., Ellis, J.A., Feldstein, N.A., and Anderson, R.C. (2006). Pitfalls for the pediatrician: positional molding or craniosynostosis? Pediatric Annals, 35(5), 365-375. Koren A., Reece, S.M., Kahn-D’angelo, L. and Medeiros, D. (2010). Parental information and behaviors and provider practices related to tummy time and back to sleep. J Pediatric Health Care, 24, 222-230. Moon RY, Darnall, RA, Goodstein MH, Hauck, FR. American Academy of Pediatrics, Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (2011). Technical Report – SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: expansion of recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics 128(5), 1030-1039. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2011-2284 Ridgeway, E.B., Berry-Candelario, J., Grondin R.T., Rogers, G.F., and Proctor, M.R. (2011). The management of sagittal synostosis using endoscopic suturectomy and postoperative helmet therapy. J Neurosurg Pediatrics, 7:620-626. Rivero-Garvia, M., Marquez-Rivas, J., Rueda-Torres, A.B. & Ollero-Ortiz, A. (2011). Early endoscopy-assisted treatment of multiple-suture craniosynostosis. Childs Nerv Syst, 28(3):427-31. Shah, M.N., Kane, A.A., Petersen, J.D., Woo, A.S., Nadoo, S. D. and Smyth, M.D. (2011). Endoscopically assisted versus open repair of sagittal craniosynostosis: the St. Louis Children’s Hospital experience. J of Neurosurg Pediatrics, 8:165-170. Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (2011). SIDS and other sleep-related infant deaths: expansion of recommendations for a safe infant sleeping environment. Pediatrics, 128(5): 1030-1039. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-2284.