Hopkinton Public Schools BSEA #05-4316

advertisement

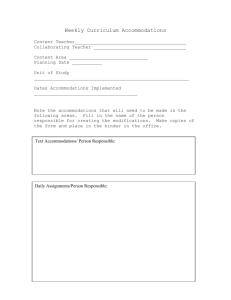

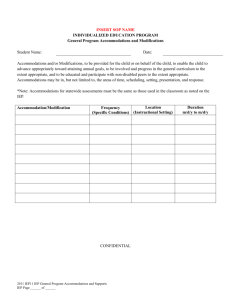

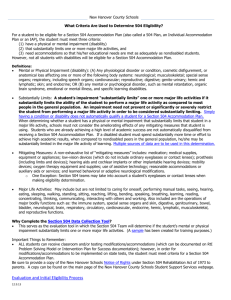

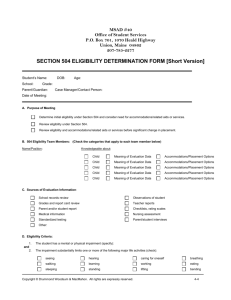

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS SPECIAL EDUCATION APPEALS In Re: Hopkinton Public Schools BSEA #05-4316 DECISION This decision is issued pursuant to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (20 USC 1400 et seq.), Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (29 USC 794), the state special education law (MGL ch. 71B), the state Administrative Procedure Act (MGL ch. 30A) and the regulations promulgated under these statutes. A hearing was held on June 7, 2005 in Malden, MA before William Crane, Hearing Officer. Those present for all or part of the proceedings were: Student’s Mother Student’s Father Eileen Antalek William Howard Johanna Dross Keith Verra Kevin Lyons Charles Vander Linden Mary Joann Reedy Psychologist, Educational Directions Teacher, Hopkinton Public Schools Teacher, Hopkinton Public Schools Guidance Counselor, Hopkinton Public Schools Assistant Superintendent, Hopkinton Public Schools Attorney for Parents and Student Attorney for Hopkinton Public Schools The official record of the hearing consists of documents submitted by the Parents and marked as exhibits P-1 through P-11; documents submitted by the Hopkinton Public Schools (Hopkinton) and marked as exhibits S-1 through S-16; and one day of recorded oral testimony and argument. As agreed by the parties and after two extensions jointly requested by the parties, written closing arguments were due on July 8, 2005, and the record closed on that date. INTRODUCTION This case requires resolution of whether Student falls within the protections of Section 504 of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973.1 Section 504 prohibits a program receiving federal financial assistance from discriminating, on the basis of handicap, against an otherwise qualified individual with a handicap. It is not disputed that Hopkinton is a program that receives federal financial assistance and that Student is “otherwise qualified”. The only issue in dispute is whether Student satisfies the definition of “handicapped person”, a necessary prerequisite to a finding of eligibility and protection under this statute. I therefore consider this issue in detail in this Decision. 1 29 USC 794. It also may be noted that this dispute is not about whether Student needs accommodations in order to be successful in learning at school. Nor, is this a dispute as to what those accommodations should be. Rather, the question presented is whether Hopkinton may provide these accommodations voluntarily pursuant to a building accommodation plan or, alternatively, whether Hopkinton must provide the accommodations pursuant to a Section 504 plan. POSITIONS OF THE PARTIES Parents’ Position. Parents take the position that their daughter has impairments that significantly limit her ability to learn, thus qualifying her for protection under Section 504. Parents seek a continuation of their daughter’s Section 504 eligibility and a continuation of the accommodations provided under her 504 plan because those accommodations have been effective, helping with her grades and her anxiety regarding school. Parents noted a particular concern regarding the loss of Section 504 accommodations for 7th grade (the next school year); Student may fail without the benefit of a 504 plan. Parents appreciate that Hopkinton has offered accommodations for their daughter through a building accommodation plan, but are concerned that it is voluntary and does not ensure accountability. Hopkinton’s Position. Hopkinton takes the position that Student is not a “handicapped person”, as that term is defined under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. Only persons who meet this definition are entitled to protection from discrimination (and therefore may receive accommodations) under Section 504. Hopkinton agrees that Student has a requisite mental or physical impairment (in this case, ADHD). However, Hopkinton argues that the impairment does not “substantially limit” Student’s major life activity of learning, with the result that she is ineligible under Section 504. Hopkinton notes that Student has been offered accommodations under a building accommodation plan pursuant to MGL c. 71, s. 38Q½. FACTS Except where specifically noted, the following facts are uncontested. Student profile. 1. Student lives with her parents in Hopkinton, MA. She recently completed the 6th grade. She is bright and hard-working. She participates successfully within mainstream classes, attaining average to above-average grades. Since the 2001-2002 school year, Student has been provided with accommodations in the classroom to address her Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Student has never been eligible to receive special education services nor is this issue in dispute. Testimony of Mother. 2 Educational history. 2. During Student’s 3rd grade (the 2001-2002 school year), her teacher expressed concern to Parents regarding Student’s attention and focusing skills, and suggested an evaluation. Hopkinton evaluated Student in March 2002, but the evaluation did not reveal any learning deficits. Testimony of Mother; Exhibit S-2. 3. Nevertheless, by the end of the 3rd grade school year, Hopkinton had begun providing a number of accommodations including the use of a white board to reinforce basic math facts and problem solving, the use of a number line on Student’s desk for a nearpoint reference model, continuing monitoring of Student’s spelling and listening skills, and use of specific, structured time for Student to check with the teacher for reinforcement and clarification. Student’s teacher reported that Student improved as a result of these interventions and that no further action was needed. Testimony of Mother; Exhibit S-1. 4. In October 2002 (Student’s 4th grade), Parents pursued their own, outside evaluation, which revealed concerns regarding focusing and understanding/following directions. Exhibits S-13, P-2. Parents did not provide this evaluation to Hopkinton until March 2005. Testimony of Mother, Lyons. 5. On March 24, 2003, Hopkinton’s Learning Support Team met and recommended the following accommodations for Student: Frequent teacher monitoring; Clarify directions by restating; Assist self-starting; Personal sequential checklist for assignment/organization provided by Parents and monitored by school; Teacher check-ins while working; Extended time for tests/class work; Preferential seating; Present multi-page tasks one at a time; Mathematics fact chart for concept development (multiplication). Exhibits S-3, P-4. 6. The Summary Record of the Learning Support Team’s meeting on March 24, 2003 concluded that Student is able to access the curriculum despite attentional issues when the above accommodations are provided. It was also noted in the Summary that Student “has a difficult time completing work within given timeframes and turning them in to the teacher. She doesn’t follow directions with care yet is a very hard worker.” Exhibits S-3, P-4. 7. The Summary Record of the Learning Support Team’s meeting also indicated that the Learning Support Team was aware that Parents had obtained an outside 3 neuropsychological evaluation in October 2002, and that Parents were concerned about ADHD, executive functioning and “memory characteristics” regarding their daughter. Exhibits S-3, P-4. 8. Around the middle of May 2003 as a result of their outside evaluation, Parents initiated a course of medication for their daughter in order to help her focus her attention. Testimony of Mother. Section 504 eligibility and accommodations. 9. On June 3, 2003 (near the end of Student’s 4th grade), Hopkinton determined that Student had an impairment of ADD (attention deficit disorder), which “substantially” limited her major life activity of “learning”, and that she was therefore eligible under Section 504 of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973. Testimony of Mother; Exhibits S-5, P-6. 10. Hopkinton initiated a Section 504 plan to provide accommodations similar to those that had been recommended by Student’s Learning Support Team (described in par. 5, above). Exhibit P-6. 11. On January 30, 2004 (mid-way through Student’s 5th grade), Student’s 504 Team met and determined that Student’s ADD continued to substantially limit her major life activity of learning, and therefore concluded that Student continued to be eligible under Section 504. The 504 Team recommended the following accommodations: Preferential seating; Frequent teacher monitoring and check-ins while working; Clarify directions by re-stating; Extended time for tests/class work; Present multi-page tasks one at a time; Personal sequential checklist for assignment/organization provided by parents and monitored at school; Graphic organizer for written assignments; MCAS accommodation # 11 – Test administrator reads/clarifies general administration instructions and test directions only; MCAS accommodation # 20 – Use of graphic organizer to generate an open response. Exhibit S-6. 12. On December 7, 2004 (mid-way through Student’s 6th grade), Hopkinton determined that Student was no longer eligible for Section 504 (see separate discussion, below, of ineligibility determination). Exhibits S-7, P-8. 4 Educational progress in 5th Grade. 13. Mother testified that prior to her daughter taking medication for her attention and prior to the initiation of the 504 plan, her daughter had a significant amount of anxiety regarding school, she took hours to complete her homework, and she needed to be in the front of the classroom in order to focus her attention. Mother explained that her daughter was nervous about school, was crying a lot, and had no interest in school. Testimony of Mother. 14. In 5th grade (the 2003-2004 school year), Mother noticed that her daughter’s anxiety about school decreased and she was able to do her homework in a “more rational way” although it still took one to two hours per night. Mother described 5th grade as a “nice” year. She explained that her daughter’s 5th grade teacher was excellent, that her daughter was calm without any significant anxiety, and that her daughter “blossomed” that year in school. Testimony of Mother. 15. Father testified that he has helped his daughter with her math homework, both before and after his daughter received 504 accommodations. He noted that she has always had difficulty with math. He explained that prior to the initiation of medications and the 504 plan, she cried at home and seemed “out of control” regarding her math homework as well as her homework for other subjects; but that with the accommodations and medication, she is more focused, although she continues to need re-direction at times. Testimony of Father. Educational progress in 6th Grade. 16. The testimony of Mother and two of Student’s teachers (Johanna Dross for English and homeroom, and William Howard for science), Student’s grades and her progress reports all indicate that she has been an excellent student during the 6th grade school year (2004-2005). Testimony of Mother, Dross, Howard; Exhibits S-7, S-10, S-12. 17. Mother reported that her daughter has done well in school during the 6th grade, enjoying school, working very hard and having little anxiety. She notes that she continues to help her daughter with her homework. Testimony of Mother. 18. The two teachers explained that Student is very hard working, often participates in class, and follows directions well. They noted that she completes her work on time, beginning her homework during the class period and completing it at home. The teachers noted that Student is generally able to keep up with her peers and follow what is being taught in the classroom, asking questions as necessary. Although she is one of the last students to complete her reading quizzes, no special time accommodations have been needed for her. Neither teacher reported any difficulties regarding Student’s academic performance other than an occasional missed homework assignment. Testimony of Dross, Howard; Exhibit S-7 (memo from Ms. Dross). 5 19. Similarly, Student’s grades and progress reports, including the memo of December 7, 2004 from Ms. Dross, reflect a conscientious and successful student. Exhibits S-7, S10, S-12. 20. The two 6th grade teachers (Ms. Dross and Mr. Howard) testified that within their classes nothing is required to be done by a student within a particular period of time within school – that is, everything can be completed at home without time constraints if a project, test or quiz cannot be completed within the class time at school. The teachers also stated that they both routinely provide all of the accommodations listed on Student’s Section 504 plan (Exhibit S-6, page 2) to all of the students in their classes, other than preferential seating and the MCAS accommodations. Testimony of Howard, Dross; Exhibit S-7 (memo from Ms. Dross). 21. At home, Student continues to have difficulty attending and following through with multi-step tasks, and even with something which she very much enjoys (for example, horseback riding), she typically cannot complete the multi-step process of getting ready to leave the house without prompts or reminders. Father noted that on timed events (including homework), she becomes nervous and anxiety-ridden. He explained that when there is a time limit for completing a homework assignment, she typically gets off task or does not do what is expected of her. Testimony of Father. Determination of ineligibility. 22. The Hopkinton 6th grade Section 504 coordinator (Keith Verra2) chaired the meeting on December 7, 2004 that resulted in a determination that Student is no longer eligible for Section 504. During the meeting, Mr. Verra asked Student’s three 6th grade teachers who attended (Elizabeth Hickey who teaches social studies, Sandy Stymiest who teaches math, and Bill Howard who teaches science) to describe how Student is doing in class. A fourth teacher (Johanna Dross who teaches English) submitted a written memo dated December 7, 2004, giving her input. Parents also attended the meeting and were invited to share their concerns. Exhibit S-7; testimony of Mother, Verra. 23. Mr. Verra testified that the three teachers explained at the meeting that Student is a hard worker, participated regularly in class, did everything that was asked of her, was organized with her materials, earned good grades, completed most of her tests and quizzes on time, and performed at a “very nice level” on a daily basis. He noted that the teachers reported very few concerns, even with respect to her attention. Testimony of Verra. 2 Keith Verra testified that currently and for the past 13 years, he has been employed by Hopkinton, for the first 8 years as a 6th grade teacher and for the next 5 years as a guidance counselor. He explained that currently he is the Hopkinton 6th grade guidance counselor. He noted that he holds a masters degree in education, which he received in 1994, and he is certified as a counselor. Mr. Verra testified that his current responsibilities include joining the teaching team meetings (each team includes 4 teachers) during which students are discussed and teacher concerns can be addressed. In addition, he is the designated 504 coordinator, he oversees all Section 504 plans and chairs all meetings regarding Section 504 eligibility for particular students, and he has attended various workshops and trainings regarding Section 504. 6 24. However, Mr. Verra and Mother agreed in their testimony that Ms. Stymiest (Student’s math teacher) took a position different than the other two teachers. Ms. Stymiest stated during the meeting that Student should continue on her 504 plan. Ms. Stymiest made clear that she believed Student required many accommodations in her math class which, presumably, would not be made available to Student absent a requirement that they be provided. Testimony of Verra, Mother. 25. Mr. Verra testified that after considering the input from Parents and the teachers during the meeting and having considered Student’s grades and progress reports, he concluded during the meeting that Student has an impairment (ADD) for purposes of Section 504, that as a result of this impairment, Student needs accommodations to be successful in school, but that Student’s impairment only moderately (rather than substantially) impacts her learning and therefore Student was not eligible under Section 504. Testimony of Verra.3 26. Mr. Verra testified that he concluded that Student’s impairment (ADD) only moderately impacted her learning for the following reasons. In his view, Student’s difficulties in math class are relevant and were factored into his consideration, but ultimately he stated that he must consider Student’s learning as a whole rather than solely within a single class. He opined that for an impairment to “substantially” limit a student’s learning, the impairment must preclude the student from engaging in learning all or most of the time – for example, during every period (or most periods) of every day. In Mr. Verra’s view, his determination that Student’s impairment only “moderately” limited her learning was appropriate because Student’s disability impacts her learning and requires an accommodation only occasionally and not in every period or during every school day. Testimony of Verra. 27. Mr. Verra testified that his determination of “moderately” impacting Student’s learning is made only on the basis of the frequency of the limitation – that is, how frequently Student’s ADD impairment interferes with or limits her learning, thus requiring an accommodation. Mr. Verra made clear that in considering how often Student’s disability required an accommodation (thereby indicating that her disability would interfere with or limit her learning), he did not take into consideration those instances where accommodations were provided to all of the students in a particular classroom – for example, in Ms. Dross’s classroom and Mr. Howard’s classroom. Testimony of Verra. 28. Mr. Verra testified that his determination of Section 504 eligibility was made only within the context of Student’s 6th grade, including her current teachers, and therefore does not pertain to any other context – for example, a different grade or different teachers. He explained that Student’s 504 eligibility can be re-considered at any time, including when she enters 7th grade in the fall of the 2005-2006 school year. He also 3 Mother testified that she felt that prior to the meeting, Mr. Verra had made up his mind to deny Section 504 eligibility to her daughter and that her “best recollection” was that the first two pages of the Hopkinton form denying her daughter eligibility had been filled out prior to the meeting, including the check-off indicating that Student’s ADD did not substantially limit her learning. Mr. Vera’s testimony was to the contrary. I find Mr. Verra’s testimony on this point more persuasive. I find that he made his determination of ineligibility only after receiving input from Parents and the teachers during the meeting. 7 noted that he only considered attentional issues relevant to Student’s diagnosis of ADD and did not consider any executive functioning or organizational concerns. Mr. Verra testified that in making his eligibility determination, he did not consider the educational implications to Student in the event that no accommodations were provided Student. Testimony of Verra. 29. Mr. Verra testified that at the December 7, 2004 eligibility meeting he did not conduct a real (or “straw”) poll of those present, nor did he consult others outside of the meeting. Rather, he made the decision himself (since he understood it to be his responsibility to do so) after considering the information provided at the meeting. Testimony of Verra. 30. After the December 7, 2004 meeting, Parents met with Hopkinton Assistant Superintend Kevin Lyons4 to discuss informally the denial of Section 504 eligibility. Later, Parents formally appealed to Dr. Lyons the determination by Mr. Verra that their daughter was no longer eligible for Section 504. Dr. Lyons affirmed Mr. Verra’s determination of ineligibility. Exhibit S-9 (Dr. Lyon’s response to Parents’ appeal); testimony of Mother, Lyons. 31. Dr. Lyons testified that he affirmed Mr. Verra’s decision because, on the basis of his own review, he concluded that Mr. Verra had followed the appropriate procedures and had made a decision that was both reasonable and correct. He noted that his appeal decision reflects a review of the appropriateness of Mr. Verra’s decision, rather than a new determination of ineligibility. Testimony of Dr. Lyons. 32. Dr. Lyons testified that there is no particular definition of “substantially” for purposes of determining eligibility under Section 504, but rather it is a judgment made in each particular instance in order to allow a student “to compete on a level playing field in the classroom”. He noted that the chart that appears on Hopkinton’s eligibility form serves as a reference tool to see where “substantially” fits on a continuum. Testimony of Dr. Lyons; Exhibit S-7, first page. 33. This eligibility chart is a column (appearing at the bottom of the left hand side of the form) listing the following nine categories relative to the degree to which a student’s impairment limits a major life activity: totally, extremely, substantially, meaningfully, frequently, moderately, infrequently, mildly, and negligibly. A student must meet the category of “substantially” to be eligible. Dr. Lyons agreed with Mr. Verra’s determination that Student met the category of “moderately”, not “substantially”. Testimony of Dr. Lyons; Exhibit S-7, first page. 4 Kevin Lyons testified that he received his PhD in reading and language education in 1981, has taught at the elementary, middle and college levels for 30 years and worked as an administrator for 8 years. He stated that he is currently employed by Hopkinton as the assistant superintendent for curriculum and operations, with one of his responsibilities as the district’s Section 504 coordinator. He explained that in this role, he reviews all Section 504 eligibility determinations, provides training to the Section 504 chairpersons (such as Mr. Verra) and generally ensures that Section 504 is implemented appropriately within the school district. He noted that he regularly attends training and reads material relevant to Section 504. He stated that the Section 504 Policies and Procedures (Exhibit S-15) are followed in Hopkinton. 8 34. Mr. Verra testified that Student’s teachers would continue to provide the needed accommodations even without being required to do so. Mother confirmed, from information from her daughter, that her teachers appear to have continued to provide her daughter with the accommodations (listed in the Section 504) after the determination of ineligibility. Testimony of Verra, Mother. Building accommodation plan. 35. Once he determined that Student was no longer eligible for Section 504 during the December 7, 2004 meeting, Mr. Verra told Parents that Student may be able to receive any necessary accommodations through a building accommodation plan, and this was briefly discussed. Mr. Verra noted that at that time, Parents did not seem interested in pursuing a building accommodation plan, with the result that although he later prepared a building accommodation plan for Student (Exhibit S-16), it was not shared with Parents. 36. Mr. Verra testified that the accommodations needed by Student in order to be successful in 6th grade are reflected in this plan (Exhibit S-16), which accommodations are essentially the same as those in the Section 504 plan that had previously been in effect for Student (Exhibit S-6). 37. The building accommodations, which have been offered Student and are reflected in Exhibit S-16, are voluntary accommodations on the part of a school district pursuant to MGL c. 71, s. 38Q½ for the purpose of helping a student to succeed. These accommodations are used as part of the pre-referral process to accommodate a student within regular education rather than referring the student to special education. Hopkinton has a general plan for this purpose (Exhibit S-11). Testimony of Lyons, Verra. 38. These accommodations may be used where a student has an impairment that impacts the student in the classroom, but not at a level to render the student eligible for Section 504. The accommodations are not considered necessary for the student to access the general curriculum. There is accountability in the implementation of these accommodations since Dr. Lyons, in his capacity as Assistant Superintendent, instructs the principals to implement them, and teachers can be disciplined for refusing to do so. The building accommodation plan is developed through a Learning Support Team that includes a student’s teachers, guidance counselor and specialists. Testimony of Lyons, Verra; Exhibit S-11. Independent evaluations of Student. 39. An organization called Educational Directions, located in Westborough, MA, performed a comprehensive evaluation of Student in October 2002. The evaluation found Student to have at least average cognitive abilities, but with anxiety, inattention and short-term memory weaknesses. The evaluation concluded that Student has ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder) with mild learning disabilities in the areas of executive function and short-term auditory memory. Student’s learning deficits generally limit her ability to access, process and produce information, and the 9 executive functioning deficits limit her organizational abilities. Exhibit S-13, P-2 (page 13); testimony of Dr. Antalek.5 40. A follow-up evaluation of Student was conducted by Dr. Antalek at Educational Directions on May 28, 2005. This evaluation included updated cognitive testing to determine what areas may be impacted by Student’s initiation of medication, as well as specific testing (the Delis-Kaplan Executive Functioning test) to look at Student’s executive functioning abilities. Testimony of Dr. Antalek; Exhibit P-1.6 41. Dr. Antalek testified (and her report reflects) that the two evaluations indicate that Student continues to have ADHD and in addition to this disability, Student has learning disabilities in the areas of executive function (organization and planning) and short-term auditory memory. Dr. Antalek noted that the ADHD exists independent of her other disabilities but likely exacerbates them. Testimony of Dr. Antalek; Exhibits S-13, P-1, P-2. 42. Dr. Antalek testified as to the implications of these disabilities for Student. She explained that if Student is presented with a short project (for example, a simple story project), she is likely to be able to complete it quickly without difficulty. Similarly, she noted that Student performs well with an objective format or where there are clear task parameters. However, with longer projects (for example, a longer reading or writing assignment that would typically be given in the 6th grade) or where more open retrieval of information is required, or with unstructured tasks, her retrieval and organizational deficits will fundamentally impact her performance. She noted that when these challenges presented themselves to Student during the evaluation, Student needed more time to complete the task – approximately one and one-half the normal time. Dr. Antalek opined that Student would need a similarly longer period of time to complete comparable schoolwork in 6th grade. Dr. Antalek opined that Student’s learning disabilities are considered to be “mild” within the overall context of her functioning at school as a bright student, but that the above-described specific deficits are significant with respect to their impact upon Student’s abilities to complete certain educational tasks successfully (as explained above) and are life-long. Testimony of Dr. Antalek; Exhibit P-1. 43. Dr. Antalek testified that her conclusions were consistent with Father’s testimony of Student’s inability to complete multi-tasks involved in getting ready for horseback 5 Eileen Antalek testified that she is currently the assistant director of Educational Directions where she has worked for the past ten years (five of which have been in her current position). She noted that she conducted the recent evaluation of Student on May 28, 2005 at Educational Directions but was not involved in the October 2002 evaluation of Student at Educational Directions. Dr. Antalek completed a master’s degree in English in February 2005, completed her doctorate (EdD) degree in education, and has been a licensed school psychologist since September 2004. Dr. Antalek testified that over the past ten years, she has been involved in approximately 100 evaluations per year; not quite half of which have involved elementary school students. She noted that the testing that she conducted of Student reflects tasks that a student would be called upon to do in school in the 6 th grade. She explained that for purposes of her testing of Student and developing her recommendations, she spoke with Parents but not with Hopkinton teachers or staff. She noted that she is not familiar with the Hopkinton 6 th grade curriculum. Testimony of Dr. Antalek; exhibit P-1. 6 Dr. Antalek had also sent a letter, dated December 13, 2004, to Parents recommending that Student’s Section 504 plan remain in place at least until Student completes her first year of high school. Exhibit P-3. 10 riding. She noted that with ADHD alone, one would expect that Student would not have these difficulties with something that she enjoys (for example, horseback riding), but that the executive functioning deficits result in her being disorganized even with activities that she enjoys. Testimony of Dr. Antalek; Exhibit P-1. 44. Dr. Antalek summarized in her report: [Student’s] overall reasoning skills are appropriately developed, but she is often inefficient and disorganized in her approach. This causes her to work impulsively and carelessly when timed, and she made many unnecessary errors. An accommodation plan and medication regime have been applied successfully, and [Student] needs continued accommodation in order to perform commensurate with her abilities. Exhibit P-1 (page 3). 45. Dr. Antalek’s report then listed the following accommodations that, she stated in her testimony, should be implemented consistently in order to address Student’s abovedescribed deficits: [Student] needs extended time to complete in-class and standardized exams, particularly when extensive reading and/or writing is required due to retrieval and organizational weaknesses. [Student] needs preferential seating within the classroom in order to facilitate focus and attention. She also needs encouragement to review task parameters before attempting new tasks. [Student] needs time to process information before responding because of executive function and retrieval weaknesses. She would benefit from brainstorming activities and visual cues to stimulate her thinking. [Student] needs a few minutes at the beginning and end of each class to organize her materials. Because of organization and memory weaknesses, [Student] should learn and use semantic mapping strategies to organize, categorize, and memorize new information. For example, timelines, charts, and graphs may be used in the notebook when reviewing classroom notes. Because [Student] has difficulty remembering facts and other rote information, she should learn to use mnemonic devices to help her recall information for exams. For example, [Student] could take the first letter from keywords and terms to create a phrase that she would write at the top of the test paper before she begins work. [Student] needs to use a homework planner to keep track of homework and due dates. In addition, a daily checklist should be incorporated into the planner that 11 includes individual tasks to complete long-term assignments. The planner will need to be checked on a daily basis by teachers and parents until these skills become automatic. All tasks should be kept short and specific. For example, a research project should be broken down into incremental tasks, with a checklist provided that [Student] can check off as she completes her work. Testimony of Dr. Antalek; Exhibit P-1.7 DISCUSSION As noted earlier in this Decision, the only issue in dispute is whether Student satisfies the definition of “handicapped person” in Section 504 of the federal Rehabilitation Act, a necessary prerequisite to a finding of eligibility and protection under this statute. I therefore consider this issue in detail below. I also note that a BSEA Hearing Officer recently considered this issue in In re: Needham Public Schools, BSEA # 04-3810, 11 MSER 19, 2526 (2004) (Berman). A. Eligibility under Section 504 Statute and regulations. Protection against discrimination pursuant to Section 504 of the federal Rehabilitation Act extends only to persons who fit within the definition of “handicapped person”. Although the statutory language of Section 504 offers little assistance in determining the meaning of this term, the regulations promulgated by the federal Department of Education pursuant to Section 504 provide the following guidance: (1) Handicapped person means any person who (i) has a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more major life activities, (ii) has a record of such an impairment, or (iii) is regarded as having such an impairment. (2) As used in paragraph (j)(1) of this section, the phrase: (i) Physical or mental impairment means (A) any physiological disorder or condition, cosmetic disfigurement, or anatomical loss affecting one or more of the following body systems: neurological; musculoskeletal; special sense organs; respiratory, including speech organs; cardiovascular; reproductive, digestive, genito-urinary; hemic and lymphatic; skin; and endocrine; or (B) any mental or psychological disorder, such as mental retardation, organic brain syndrome, emotional or mental illness, and specific learning disabilities. (ii) Major life activities means functions such as caring for one's self, performing manual tasks, walking, seeing, hearing, speaking, breathing, learning, and working.8 7 Dr. Antalek, in her testimony, also made reference to parts of three exhibits that describe generally the nature of Student’s disability. Exhibits P-9, P-10, P-11. I reference these exhibits here although I do not find that they enhance my understanding of Student’s particular disability and its limitations on her ability to learn. 8 34 CFR 104.3(j) (emphasis added). 12 This language makes clear, and the First Circuit Court of Appeals has confirmed, that to be considered a “handicapped person”, Student must meet two criteria – first, she must have one or more of the requisite mental or physical impairments (or have a record of such an impairment or be regarded as having such an impairment) and second, the impairment(s) must “substantially limit” one or more of her major life activities.9 Both parties in the instant dispute acknowledge that Student has one or more mental or physical impairments that satisfy the first criteria for eligibility under Section 504. 10 The parties further agree that Student’s impairments limit, at least to some degree, her major life activity of learning. The crux of their disagreement is whether Student’s impairments limit her learning to a sufficient degree – that is, to a “substantial” degree, as required by the above-quoted regulatory language. Case law. In considering the question of whether Student’s impairments substantially limit her major life activity of learning, I turn to case law interpreting Section 504. Case law interpreting the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) will also be considered since the First Circuit Court of Appeals has concluded that case law construing the ADA generally pertains equally to claims under the Rehabilitation Act.11 The United States Supreme Court, as well as several lower federal courts, have had occasion to discuss and provide guidance regarding the meaning of “substantially limits” as that phrase is found within the above-quoted definition of “handicapped person”. In a 2004 decision, the First Circuit summarized this general guidance as follows: Although the federal statutes do not explicitly define the phrase "substantially limits," in Sutton the Supreme Court instructed that the phrase suggests “considerable” or “specified to a large degree.” Even so, while substantial limitations should be considerable, they also should not be equated with “utter inabilities.” The Supreme Court has stated that "[w]hen significant limitations result from an impairment, the disability definition is met even if the difficulties are not unsurmountable." An impairment can substantially limit a major life activity, even though the plaintiff is still able to engage in the activity to some extent.12 In addition, the Supreme Court has described certain principles when making a determination as to whether an impairment substantially limits a major life activity. First, the Supreme 9 E.g., Calero-Cerezo v. U.S. Dept. of Justice, 355 F.3d 6, 20 (1st Cir. 2004) (general discussion of eligibility under Section 504). 10 Hopkinton concedes that Student has ADHD and that this impairment satisfies the requirement, under Section 504, that Student have a mental or physical impairment. The First Circuit Court of Appeals has concluded that, in an appropriate case, a diagnosis of ADHD may be a mental impairment within the meaning of Section 504’s definition of handicapped person. Bercovitch v. Baldwin School, Inc., 133 F.3d 141, 155 n.18 (1st Cir. 1998). As discussed later in this Decision, the evidence further reflects that Student has additional learning disabilities. 11 Calero-Cerezo v. U.S. Dept. of Justice, 355 F.3d 6, 19 (1st Cir. 2004); Bercovitch v. Baldwin School, Inc., 133 F3d 1411, 151 n.13 (1st Cir. 1998) and cases cited therein. 12 Calero-Cerezo v. U.S. Dept. of Justice, 355 F.3d 6, 21-22 (1st Cir. 2004) (internal quotations and citations omitted). 13 Court has made clear that whether a person may be considered a “handicapped person” under the statute is decided with respect to each individual, requiring that the determination be made on a case-by-case basis.13 Second, a person seeking eligibility must "be presently — not potentially or hypothetically — substantially limited to demonstrate the requisite disability."14 Third, the determination of whether an individual is substantially limited in a major life activity must take into account mitigating measures such as medication taken by the individual as well as any compensating strategies (such as hard-work) utilized by the individual. In other words, the person’s impairments must be determined to substantially limit a major life activity after the mitigating measures have been taken into account.15 Fourth, the limitations of the major life activity (for example, learning) are considered in comparison to an average person (or “most persons”) within the general population.16 For purposes of a student’s seeking Section 504 eligibility, the First Circuit Court of Appeals has instructed that the comparison is to an “average student his age”.17 For a more comprehensive discussion of this issue, see footnotes 24, 25 and 26, below, and accompanying text. Fifth, the impact of the impairment(s) must be “permanent or long term”.18 Sixth, it is insufficient for an individual attempting to establish eligibility merely to submit evidence of a medical diagnosis of an impairment. Instead, Section 504 requires those "claiming the Act's protection . . . to prove a disability by offering evidence that the extent of the limitation [caused by their impairment] in terms of their own experience . . . is substantial."19 With these principles in mind, I turn to the evidence presented in this case. Consideration of the evidence. As noted above, there is no disagreement that Student has impairments sufficient to meet the first prong of the definition of “handicapped person”. Hopkinton agrees that Student’s ADHD satisfies this standard. There was also unrebutted expert testimony and evaluation reports, and I so find, that, additionally, Student has learning disabilities in the areas of executive functioning (organization and planning) and short-term auditory memory. Facts 13 Toyota Motor Mfg., Ky., Inc. v. Williams, 534 U.S. 184, 198 (2002); Sutton v. United Airlines, Inc., 527 U.S. 471, 483 (1999). 14 Sutton v. United Air Lines, Inc., 527 U.S. 471, 482 (1999). 15 Murphy v. United Parcel Service, Inc., 527 U.S. 516, 521 (1999); Albertson's Inc. v. Kirkingburg, 527 U.S. 555, 565-67 (1999). 16 Sutton v. United Air Lines, Inc., 527 U.S. 471, 491 (1999); Toyota Motor, Mfg., KY. Inc. v. Williams, 534 U.S. 184, 200-201 (2002) 17 Bercovitch v. Baldwin School, Inc., 133 F.3d 141, 156 (1st Cir. 1998). 18 Toyota Motor Mfg., Ky., Inc. v. Williams, 534 U.S. 184. 198 (2002). 19 Albertson's, Inc. v. Kirkingburg, 527 U.S. 555, 567 (1999). 14 Section of this Decision (Facts), pars. 39, 41. It is the effect of this combination of impairments on Student’s learning that must be considered.20 There is little, if any, disagreement as to the limitations on Student’s learning as a result of her impairments. However, there is relatively little evidence in this dispute as to the impact of those limitations on her learning when the necessary accommodations are not provided. This is because all of Student’s needed accommodations have been provided during at least the past two school years, and therefore progress reports and grades during that time period do not indicate the impact of Student’s impairments on her learning. Grades and progress reports prior to this time would be dated, and would have been prior to Student’s beginning medication to address her ADHD. For these reasons, the determination of Student’s actual learning limitations, as a result of her impairments, is necessarily grounded on (1) a recent formal evaluation of Student’s impairments, (2) recent anecdotal situations at home or in the community, and (3) what accommodations continue to be necessary in order that Student be successful at school. I find that Parents have provided credible, unrebutted evidence that Student’s impairments limit her learning in the following ways. Student’s retrieval and organizational deficits negatively and fundamentally impact her performance with relatively long projects (for example, a longer reading or writing assignment that would typically be given in the 6th grade) as compared, for example, to a simple story project. Facts, par. 42. Student’s retrieval and organizational deficits negatively and fundamentally impact her performance where relatively open retrieval of information is required or with unstructured tasks as compared, for example, to assignments with an objective format or where there are clear task parameters. Facts, par. 42. A practical implication of Student’s difficulty completing these educational tasks is that Student generally requires one and one-half the amount of time normally needed for a 6th grader to complete these same tasks. Facts, par. 42. In addition, Student’s impairments cause her often to be inefficient and disorganized in her approach. This causes her to work impulsively and carelessly when timed, with the result that she makes many unnecessary errors. Facts, par. 44. Student’s executive functioning impairments result in a level of disorganization that makes her unable to complete multi-task assignments without cuing, even when the task is something that she enjoys in the community such as getting ready for horseback riding. Facts, pars. 21, 43. 20 I note that Parents did not share their evaluations with Hopkinton until relatively recently and, as a result, Hopkinton argues that I should consider only Student’s ADHD. However, on or before March 24, 2003, Hopkinton was aware of Parents’ October 2002 evaluation as well as Parents’ concerns regarding Student’s executive functioning and memory limitations. Exhibit S-3. There is no indication that Hopkinton ever sought to obtain this evaluation from Parents or that it was ever precluded from further evaluating Student to determine, for itself, whether Student has these learning disabilities. 15 Student’s impairments are considered to be life-long. Facts, par. 42. There is no disagreement that Student requires accommodations in order to be successful in learning at school.21 The relevance of this inquiry was made clear by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals: “learning-impaired student may properly be considered to be disabled [under Section 504 and the ADA] if he could not have achieved success without special accommodations”.22 There also is no disagreement that the accommodations needed by Student are those reflected within her most recent Section 504 plan, which are substantially the same as those recommended in Dr. Antalek’s evaluation.23 Essentially the same accommodations have been provided Student during at least the last two school years. Facts, pars. 5, 10, 11, 34. The accommodations reflected within Student’s most recent Section 504 plan and those recommended by Dr. Antalek reflect, at least implicitly, that Student has significant, practical deficits regarding attention, organization, and retrieval and processing of information. It is apparent that these deficits substantially impact her learning in a variety of settings. Finally, I take note of the fact that Hopkinton twice determined Student to have an impairment that substantially limited her ability to learn, making her eligible under Section 504. When Hopkinton determined that Student was no longer eligible, no determination was made that Student’s impairment had somehow improved or that her impairment limited her learning any less than when she was found eligible under Section 504. Instead, Hopkinton determined only that Student did not require accommodations (over and above those provided to all students) most of the time – that is, an analysis of frequency of need for an accommodation. (For reasons explained below, I believe that this method of determining Section 504 eligibility is flawed.) The unrebutted evidence (from Dr. Antalek’s testimony and the two independent evaluations) is that Student’s impairments have essentially remained the same from the time they were first identified in an independent evaluation in October 2002 through Dr. Antalek’s evaluation of Student on May 28, 2005. Facts, pars. 9, 11, 26, 27, 39, 40, 41. On the basis of this evidence, I find that Student’s impairments restrict her ability to perform activities and tasks that are of central importance to her education, with the result that Student’s impairments impose significant limitations on her learning. Without these accommodations, Student cannot be successful in learning at school. I make these findings with respect to Student in comparison to the average student her age and after taking into account the medication she is taking and her compensating strategies (that include working Hopkinton’s closing argument at page 14 (“[P]arents have argued that [Student] continues to need accommodation in order to succeed. Hopkinton Public School agrees.”) In their testimony, Mr. Verra and Dr. Lyons agreed. Facts pars. 25, 37. 22 Wong v. Regents of University of California 01-17432 (9th Cir. 2004). 23 When Student was found not eligible for Section 504, Hopkinton continued to implement these same accommodations for the remainder of the 6th grade year. Hopkinton also proposed to continue many of these accommodations through a more informal building accommodation plan. Mr. Verra testified that the accommodations that Student needs to be successful are reflected in the proposed building accommodation plan, which he believes to be essentially the same as those described in Student’s most recent Section 504 plan. Facts, pars. 34, 35, 36. 21 16 very hard). I further find that the impact of Student’s impairments is, at least, long term and probably permanent. Hopkinton’s basis for determination of ineligibility. Hopkinton argues that the extent to which Student’s impairments limit her learning must be gauged in the context of the particular 6th grade classrooms in which Student’s learning has been taking place. In at least two of Student’s 6th grade classrooms, the teachers routinely provided to all children the accommodations needed by Student, with the exception of the accommodation of sitting in the front of the room and the accommodations for taking the MCAS test. The result has been that at least in these two classrooms, Student has had little need for additional accommodation. Hopkinton’s Section 504 Coordinator (Mr. Verra) conceded the need for individual accommodations in a third classroom – math – but reasoned that the need for accommodations in a single classroom was not sufficient to meet the “substantially limits” eligibility requirement. Facts, pars. 25, 26. In determining that Student’s impairments did not substantially limit her learning, Hopkinton applied a test of how frequently Student required an accommodation over and above what was provided routinely to all of the children in the classroom. As Mr. Verra explained in his testimony, Student did not need a teacher to provide her with an additional accommodation all or even most of the time. This was because accommodations needed by Student were being provided to all children in several of Student’s classes. Hopkinton concluded that Student was not eligible under Section 504. Facts, par. 27. For reasons discussed below, within the relevant case law and federal regulations, I find no support for Hopkinton’s determination of ineligibility based on a consideration of Student’s impairments, as they impact upon her learning only within the particular educational context of her 6th grade classrooms. When seeking to understand the implications of the phrase “substantially limits” within the context of Section 504 and the ADA, the courts have routinely referred to and relied upon the Department of Justice (DOJ) regulations implementing Section 504 and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) regulations implementing the ADA. EEOC regulations define "substantially limits" as "[s]ignificantly restrict[s] as to the condition, manner or duration under which an individual can perform a particular major life activity as compared to the condition, manner, or duration under which the average person in the general population can perform that same major life activity."24 The DOJ regulations do not define the phrase "substantially limits," but the preamble to the regulations provides: "A person is considered an individual with a disability . . . when the individual's important life activities are restricted as to the conditions, manner, or duration under which they can be performed in comparison to most people."25 24 25 29 C.F.R. § 1630.2(j)(1)(ii) (emphasis added). 28 C.F.R. Pt. 35, App. A § 35.104 (1999) (emphasis added). 17 In addition, case law makes clear that the appropriate context for considering the impact of an impairment is not the particular setting in which the individual is seeking an accommodation -- for example, a particular job for which the individual has applied, a particular examination that needs to be taken, a particular educational curriculum or a particular school. Rather, the inquiry must consider the nature and implications of the impairment in a broader and more general context -- for example, the ability to perform “a broad range of jobs in various classes”, or the ability “to learn as a whole” or to learn “generally”, and the inquiry includes a comparison to most people or the average person in the general population.26 For these reasons, I do not agree with Hopkinton’s determination of ineligibility based only on the limited context of Student’s particular classrooms and teachers during her 6th grade year. Student’s impairments must be considered as they exist presently (not hypothetically or in the future) but, at the same time, from a more global perspective – that is, her learning as a whole. Her impairments must also be measured within the context of the general population of children at her age level. From this vantage point, I find that Student’s impairments substantially limit her ability to learn, for the reasons already described. 27 26 E.g., Sutton v. United Air Lines, Inc., 527 U.S. 471, 491 (1999) (inquiry under EEOC regulations is whether individual was “significantly restricted in the ability to perform either a class of jobs or a broad range of jobs in various classes as compared to the average person having comparable training, skills and abilities” rather than whether the individual was substantially limited in the ability to perform a particular job – for example, the job of commercial airline pilot for which the individual applied); Toyota Motor, Mfg., KY. Inc. v. Williams, 534 U.S. 184, 200-201 (2002) (“When addressing the major life activity of performing manual tasks, the central inquiry must be whether the claimant is unable to perform the variety of tasks central to most people's daily lives, not whether the claimant is unable to perform the tasks associated with her specific job.”); Emory v. Astrazeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, 401 F.3d 174 , 179-180 (3rd Cir. 2005) (“essence of the inquiry regards comparing the conditions, manner, or duration under which the average person in the general population can perform the major life activity at issue with those under which an impaired plaintiff must perform”); Ristrom v. Asbestos Workers Local 34, 370 F.3d 763 (8th Cir. 2004) (inquiry is whether the individual “has produced evidence to prove his asserted impairments . . . limit his ability to learn to a considerable or large degree as compared to the average person in the general population”); Wong v. Regents of University of California 01-17432 (9th Cir. 2004) (relevant inquiry is not whether individual could keep up with a particular medical school curriculum, but whether his impairment “substantially limited his ability to learn as a whole, for purposes of daily living, as compared to most people”); Gonzales v. National Bd. of Medical Examiners, 225 F.3d 620 (6th Cir. 2000) (in determining whether substantial life activities of reading and writing are “substantially limited”, inquiry is the condition, manner, or duration under which the major life activity can be performed in comparison to most people, rather than individual’s need for extended time to take the medical licensing examination); Bartlett v. New York State Board of Law Examiners, 226 F.3d 69, 80 (2nd Cir. 2000) (“ultimate question is whether Bartlett's lack of automaticity and slow rate of reading amount to a substantial limitation in comparison to most people" rather than need for an accommodation to take the state bar exam); Bercovitch v. Baldwin School, Inc., 133 F.3d 141, 155-156 (1st Cir. 1998) (relying on ADA regulations that provide that individual must be “[s]ignificantly restricted as to the condition, manner or duration under which [he] can perform a particular major life activity as compared to the condition, manner, or duration under which the average person in the general population can perform that same major life activity”); Soileau v. Guilford of Maine, Inc, 105 F.3d 12, 15-16 (1st Cir. 1997) ("Impairment is to be measured in relation to normalcy, or, in any event, to what the average person does."); Knapp v. Northwestern Univ., 101 F.3d 473, 481 (7th Cir. 1996) (with respect to an impairment that affects the major life activity of learning, "[t]he impairment must limit [learning] generally”); Darian v. Univ. of Massachusetts Boston, 980 F. Supp. 77, 87 (D.Mass. 1997) (Gertner, J.) (holding that nursing student was disabled because impairment "substantially interfere[d] with her ability to fully participate in an education program" not just a nursing program). See also In re: Needham Public Schools, BSEA # 04-3810, 11 MSER 19, 25-26 (2004) (Berman) (discussing federal case law relevant to meaning of phrase “substantially limits”). 27 I similarly note the inappropriateness of determining whether an impairment substantially limits a major life activity on the basis of how frequently an accommodation is needed, which is the approach utilized by the Hopkinton Section 504 coordinator. I am not aware of a single judicial or administrative decision that has determined whether an impairment substantially limits a major life activity on this basis. 18 Student’s academic success. Relying on a Connecticut special education Hearing Officer’s decision, Hopkinton further argues that where a student with a mental or physical impairment achieves at least average grades, positive teacher reports and completed homework assignments, the impairments will not be considered to “substantially limit” her learning.28 Although the Connecticut decision provides a useful analysis, I do not find it relevant to the instant dispute. There is nothing within the Connecticut decision that indicates that the student was receiving accommodations at the time that she was obtaining satisfactory grades and teacher reports, and completing her homework assignments. In contrast, Hopkinton relies upon Student’s success in the classroom during those times when necessary accommodations were being provided to her under her Section 504 plan. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals has further explained: That is not to say that a successful student by definition cannot qualify as "disabled" under the Acts. A blind student is properly considered to be disabled, because of the limitation on the major life activity of seeing, even if she graduates at the top of her class. Nor do we say that a successful student cannot prove "disability" based on a learning impairment. A learning-impaired student may properly be considered to be disabled if he could not have achieved success without special accommodations.29 Hopkinton agrees that Student’s accommodations are necessary for her to be successful in learning at school.30 There is no doubt that Student’s successes at school are, to a significant extent, attributable to the accommodations that she has received pursuant to her Section 504 plan. Therefore, reliance upon those successes is not persuasive that Student is not sufficiently impaired to be eligible under Section 504. Hopkinton also points out that it is willing to provide, voluntarily, essentially all of the accommodations that Student needs through a building accommodation plan. It is apparent that what Hopkinton chooses to provide a student to accommodate her impairments is not relevant to a determination of whether those impairments substantially limit her learning. Conclusion. For these reasons, I conclude that Student is eligible under Section 504 of the federal Rehabilitation Act of 1973. 28 Westport Board of Education, Connecticut State Education Agency , 40 IDELR 85 (2003). Wong v. Regents of University of California 01-17432 (9th Cir. 2004). See also Singh v. George Washington University, 368 F. Supp.2d 58, 66 (D.C. 2005) (prior academic success irrelevant in determining student’s ability to take timed multiple-choice tests); Rush v. National Bd. of Medical Examiners, 268 F. Supp.2d 673 (N.D.Tex. 2003) (notwithstanding history of significant academic success, individual found to have a disability that entitled him to an accommodation under the ADA). 30 See footnotes 22 and 23, above, and accompanying text. 29 19 B. Accommodations under Section 504 At the beginning of the evidentiary Hearing, it appeared that in the event that I decided that Student is eligible under Section 504, I would then need to determine what accommodations, if any, should be provided Student pursuant to Section 504. However, at the end of the evidentiary Hearing, Parents’ attorney indicated that Parents sought the accommodations recommended by their expert, Dr. Antalek, and Hopkinton’s attorney responded that in the event that I were to conclude that Student is eligible under Section 504, Hopkinton would not object to the provision of Dr. Antalek’s recommended accommodations. I anticipate that, in light of this Decision, a Section 504 meeting will occur prior to the beginning of the 2005-2006 school year to determine Student’s accommodations for 7th grade. In the unlikely event that the parties cannot reach agreement, they may return to the BSEA to resolve their dispute. I conclude that, at present, there is no dispute between the parties regarding the accommodations required by Student pursuant to Section 504, and I therefore decline to make further findings or to issue an order regarding this aspect of the case. ORDER Student is eligible pursuant to Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. By the Hearing Officer, William Crane Dated: July 19, 2005 31 31 I commend both parties and their attorneys. Hopkinton teachers and staff demonstrated their commitment to Student’s education, including the provision of accommodations necessary to allow her to succeed. Parents’ commitment to their daughter is self-evident. They also made clear their appreciation for the excellent Hopkinton teachers who have worked with their daughter. Both attorneys are highly skilled, and represented their clients effectively, efficiently and without rancor. This was simply a case where all agreed that they have a disagreement in principle that required resolution by the BSEA. I also note, with appreciation, the helpful assistance provided by BSEA legal intern Sarah Wilhite in researching relevant case law and regulations for this Decision. 20 COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS BUREAU OF SPECIAL EDUCATION APPEALS EFFECT OF BUREAU DECISION AND RIGHTS OF APPEAL EFFECT OF THE DECISION 20 U.S.C. s. 1415(i)(1)(B) requires that a decision of the Bureau of Special Education Appeals be final and subject to no further agency review. Accordingly, the Bureau cannot permit motions to reconsider or to re-open a Bureau decision once it is issued. Bureau decisions are final decisions subject only to judicial review. Except as set forth below, the final decision of the Bureau must be implemented immediately. Pursuant to M.G.L. c. 30A, s. 14(3), appeal of the decision does not operate as a stay. Rather, a party seeking to stay the decision of the Bureau must obtain such stay from the court having jurisdiction over the party's appeal. Under the provisions of 20 U.S.C. s. 1415(j), "unless the State or local education agency and the parents otherwise agree, the child shall remain in the then-current educational placement," during the pendency of any judicial appeal of the Bureau decision, unless the child is seeking initial admission to a public school, in which case "with the consent of the parents, the child shall be placed in the public school program". Therefore, where the Bureau has ordered the public school to place the child in a new placement, and the parents or guardian agree with that order, the public school shall immediately implement the placement ordered by the Bureau. School Committee of Burlington, v. Massachusetts Department of Education, 471 U.S. 359 (1985). Otherwise, a party seeking to change the child's placement during the pendency of judicial proceedings must seek a preliminary injunction ordering such a change in placement from the court having jurisdiction over the appeal. Honig v. Doe, 484 U.S. 305 (1988); Doe v. Brookline, 722 F.2d 910 (1st Cir. 1983). Compliance A party contending that a Bureau of Special Education Appeals decision is not being implemented may file a motion with the Bureau of Special Education Appeals contending that the decision is not being implemented and setting out the areas of non-compliance. The Hearing Officer may convene a hearing at which the scope of the inquiry shall be limited to the facts on the issue of compliance, facts of such a nature as to excuse performance, and facts bearing on a remedy. Upon a finding of non-compliance, the Hearing Officer may fashion appropriate relief, including referral of the matter to the Legal Office of the Department of Education or other office for appropriate enforcement action. 603 CMR 28.08(6)(b). 21 Rights of Appeal Any party aggrieved by a decision of the Bureau of Special Education Appeals may file a complaint in the state superior court of competent jurisdiction or in the District Court of the United States for Massachusetts, for review of the Bureau decision. 20 U.S.C. s. 1415(i)(2). Under Massachusetts General Laws, Chapter 30A, Section 14(1), appeal of a final Bureau decision to state superior court must be filed within thirty (30) days of receipt of the decision. The federal courts have ruled that the time period for filing a judicial appeal of a Bureau decision in federal district court is also thirty (30) days of receipt of the decision, as provided in the Massachusetts Administrative Procedures Act, M.G.L. c.30A. Amann v. Town of Stow, 991 F.2d 929 (1st Cir. 1993); Gertel v. School Committee of Brookline, 783 F. Supp. 701 (D. Mass. 1992). Therefore, an appeal of a Bureau decision to state superior court or to federal district court must be filed within thirty (30) days of receipt of the Bureau decision by the appealing party. Confidentiality In order to preserve the confidentiality of the student involved in these proceedings, when an appeal is taken to superior court or to federal district court, the parties are strongly urged to file the complaint without identifying the true name of the parents or the child, and to move that all exhibits, including the transcript of the hearing before the Bureau of Special Education Appeals, be impounded by the court. See Webster Grove School District v. Pulitzer Publishing Company, 898 F.2d 1371 (8th Cir. 1990). If the appealing party does not seek to impound the documents, the Bureau of Special Education Appeals, through the Attorney General's Office, may move to impound the documents. Record of the Hearing The Bureau of Special Education Appeals will provide an electronic verbatim record of the hearing to any party, free of charge, upon receipt of a written request. Pursuant to federal law, upon receipt of a written request from any party, the Bureau of Special Education Appeals will arrange for and provide a certified written transcription of the entire proceedings by a certified court reporter, free of charge. 22