Walking the Medieval Pilgrimage Road to

advertisement

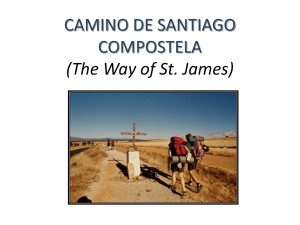

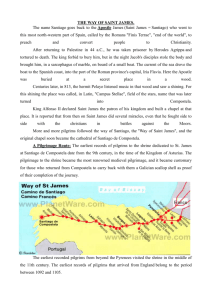

Bilkent University The Department of Archaeology & History of Art Newsletter No. 3 - 2004 Walking the Medieval Pilgrimage Road to Santiago de Compostela Fig. 1 San Juan de Ortega (Spain) Spring semester, 20022003, I took a leave of absence from my teaching duties here at Bilkent. The book I had been working on for many years was at last finished (Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece, and Rome, London and New York: Routledge, 2003), so it was time for a break. I spent the first three months in Athens, working in the great library of the American School of Classical Studies. I was investigating especially the history of excavation in Cilicia and Hatay, with a focus on the importance given in these research projects to the Achaemenid Persian period (ca. 550-330 BC). In late April, I left Athens and Ankara and flew to Paris to begin a completely different activity: hiking the famous late Medieval pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela, in northwest Spain. My older daughter, Caroline, agreed to come with me. Fig. 2 Pilgrimage Routes in France and Spain 20 Together, we took the train to Le Puy-en-Velay, in south central France, one of the four classic starting points in France. From here we walked 750 km to the Spanish border, crossed the Pyrenees, then walked an additional 750 km to Santiago. The trip took us 60 days; we hiked for 58 of those days, resting for two – a tiring schedule I would happily have stretched out over an additional week, if I had had the time. Initiated in the 9th-10th centuries after the discovery of the tomb of James, a disciple of Jesus Christ, in northwest Spain, the pilgrimage to Santiago ranked third in importance, after Jerusalem and Rome, as a religious journey for western European Christians. In the 16th century, with the Bilkent University The Department of Archaeology & History of Art Newsletter No. 3 - 2004 Fig. 3 Spain) Entering Galicia (NW Protestant Reformation and resultant religious wars in France and other regions to the north, the international character of the pilgrimage was much reduced. In the past two decades, interest in walking this trail has revived. The route has been declared a European Cultural Itinerary, and Pope John Paul II, visiting Santiago in 1989, gave an important endorsement. To be an official pilgrim (and receive a Certificate from cathedral authorities in Santiago), you need only have walked the last 100 km or cycled the last 300 km. Thousands have walked or cycled the route during the past twenty years, most for much longer than 100300 km. All are labeled “pilgrims,” and carry a small booklet, or “passport,” that declares a religious motivation (this “passport” is required in Spain if you wish to stay in the many low-cost hostels established by cities and towns for pilgrims). People walk the route for a variety of reasons, however: not only spiritual, but also cultural and physical, the sheer pleasure of hiking. I myself was attracted by this mix. For one, I wanted to do a long hike. In the 1980s, I had hiked in the Himalayas (in Nepal and Kashmir), around Mont Blanc (France, Italy, Switzerland), and in Yosemite Park (California), and loved it. In the 1990s, when I joined the Kinet Höyük excavations, there was no longer the time for such hikes, to my regret. Second, this route promised a great variety of things to see, including Romanesque churches at Conques and Moissac that I teach in my first year course, “Survey of European Art and Architecture.” And last, I looked forward to the spiritual dimensions, an opening up of the soul as I walked through the countryside, villages, and towns, an expression of thanks and joy for the many blessings in my life, including, of course, finishing Ancient Cities. Caroline and I, carrying backpacks of approx. 9 kg (Caroline) and 12 kg (me), walked an average Fig. 4 Soyarza Chapel, near Ostabat (SW France) 21 of 25 km each day. Trail conditions varied, from narrow forest paths to unpaved and even paved roads. In France, there were more hills to climb and descend, although in Spain we hiked up and over three sets of mountains. The French route passes through beautiful countryside, farms, villages, and small towns. The largest is Cahors, a town of 25,000 dating from Roman times and strategically located on a bend in the Lot River. In Spain, in contrast, large cities dot the route, Pamplona, Burgos, Leon, and Santiago itself. As a result, before reaching the historic city centers, one spends much time crossing dull outskirts. We stayed in the hostels established to serve hikers and cyclists. In France, these hostels are often privately owned, although some are sponsored by municipalities and religious groups. Kitchens are available, but we signed up for Bilkent University The Department of Archaeology & History of Art Newsletter No. 3 - 2004 prepared dinners and breakfasts whenever offered. Dinner with 5-15 others was an excellent way to meet other pilgrims. People of many nationalities and a variety of occupations treated France and Spain, the hostels are dormitories, men and women together. This group living can be wearing: the snoring, the early leavers rustling around as they prepare their packs, the Fig. 5 St. James (18th c., Cathedral, Santiago) each other in a friendly, relaxed manner – a model of how human relationships should be. In Spain, municipalities run the majority of hostels. Facilities are simpler, prices much lower (3-5 euros per night, per bed). In both ← Previous article hot water that has run out, the stuffy air from windows shut at night… So from time to time we treated ourselves to a hotel. When we reached Santiago, we performed the rituals that all pilgrims do, shared even by those 22 not particularly religious. We visited the old Romanesque portal, putting our fingers into well-worn holes on the sculpted Tree of Jesse and saluting the sculptor himself, portrayed in stone, by touching our head to his. Then we climbed up behind the main altar and embraced from behind the medieval gold-covered statue of St. James, and descended into the crypt to pay our respects to his remains, kept in a silver casket. Finally, we attended the Mass held for pilgrims every day at noon. The nationalities and places of departure of those pilgrims who have arrived during the previous 24 hours are read out: such as, “from Le Puy, two Americans, one Belgian, two French…” And for us, a special treat, because we arrived on a special day, 24 June, the Feast of St. John the Baptist (patron saint of Quebec): at the end of the Mass, the cathedral’s famous “botafumeiro,” the huge (80 kg) silver incense burner, was hoisted up on a pulley by eight men and swung back and forth, higher and higher, faster and faster. I held my breath – wouldn’t it fly out of control? But eventually down it came, the Mass ended, and then we went out to enjoy two more days of sightseeing, relaxing, talking with friends made on the long journey before we headed back home, to Ankara and to New York. Charles Gates Next article →