Kelsen - The University of Sydney

advertisement

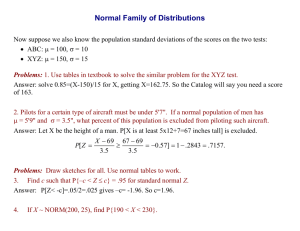

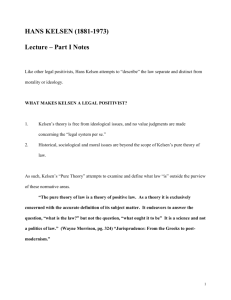

1 JURISPRUDENCE SYDNEY UNIVERSITY BRIEF NOTES FOR STUDENTS – GUIDE TO ISSUES ONLY – WILL NOT REPLACE EXAM PREPARATION Sophie York Not for publication or transfer without permission. The Philosophy of Law: From Kelsen to Human Rights Theory Harris Chapter 6 (Kelsen) p 64 Brian Bix Chapter 4 (Kelsen) p57 McCoubrey & White (Kelsen) p 43 Hans Kelsen (1881-1973) Austrian legal theorist, prolific and influential. Modern legal positivist. Described his theory in German as “reine Rechtslehre” or in English “a pure theory of law”, a ‘science of norms’. Thought that moral judgements, political biases and sociological conclusions should be put aside for the purposes of divining what was pure law. Kelsen wanted to isolate what was unique to legal structures. It was a pure theory because it would describe law without reducing it to psychology, sociology or the like. This distinguished Kelsen’s views from the Scandinavian realists. In describing it as a science of norms Kelsen wanted a description of the structure of law that was free of evaluative terms. He thought 1.Normative claims (how things ought to be or how people ought to act) can only be legitimised only by reference to other normative claims. 2. Such lines of justification come to an end at some point. 2 Kelsen did not have religious faith. He theorised that there was a foundational argument presupposed by law, in a comparable way to the one implied by a religious-based statement. He also looked at actions and worked out what actions were normative actions eg putting slips of paper into a box – voting. Kelsen characterised laws as rules or norms. Laws are always part of a system of norms having relationships of validity which they derive from higher norms. A norm was a valid norm if a higher norm authorised the making of the lower norm and it had been made in accordance with the higher authorising law. The Grundnorm Kelsen recognised that the chains of validity do not regress indefinitely and one will ultimately run out of higher authorising valid norms. What confers validity on the system as a whole is not therefore another positive rule of law but what Kelsen called the grundnorm sometimes translated as ‘basic norm’. Kelsen described the grundnorm as the fundamental assumption made by people in society about what would be treated as law. It is not the constitution, which for Kelsen was simply another positive norm. P58 Bix “It is the understanding that eventually we will come to a point either so foundational, or so early in society’s legal theory that one cannot go further back, and no further justification can be offered”. Asserting the normative validity of a particular legal rule (eg you cannot park here) is to implicitly affirm the validity of the foundational link of the chain. This affirmation of the underlying belief in the system is what Kelsen called the affirming the “Grundnorm”. eg in religion you might say you cannot do x and y because God says, and that is your foundational belief… if you follow the basic norm it is because you believe in what Parliament says and the authority Parliament had for passing the norms/laws. It is apparent that what particular grundnorm applies in a society simply depends upon what fundamental assumptions are made by the members of that society. The identity of the grundnorm is ultimately a matter of sociological fact. (No moral or other judgement or assessment is being made about it). 3 Some people have argued that it follows from Kelsen’s theory that if the assumption should change as a result of a revolution or coup d’état, and people apply the new assumption, then laws made with the new assumption will be valid. Kelsen’s theory appears consistent with maxim “might is right”. Whether or not this controversial assumption flows from Kelsen’s theory has been considered in cases involving radical norm change. See: The Republic of Fiji v Chandrika Prasad (Court of Appeal of Fiji Islands, 1 March 2001) and; On a decision in Australian law about what appears to constitute the grundnorm Trethowan v Attorney General for New South Wales (1931) 44 CLR 394; and [1932] AC 526, in which it was held that the relevant provision of the Constitution Act was a law which deprived the legislature of the requisite power. The Privy Council concluded that the words “manner and form” were amply wide to comprehend a requirement that a Bill must be put to referendum prior to its valid passage. On appeal, the Privy Council upheld the High Court’s decision. Summarising Kelsen: 2 things universally true of law: - coercive - system of norms and all legal norms could be understood in terms of an authorisation to an official to impose sanctions. A does X (wrong act), B imposes Y (sanction) and it applied in both civil and criminal law (see Bix). Concept of the basic norm: 4 questions to be asked: [see Harris] 1.Its nature 2.content 3.function 4.how to choose between competing basic norms Basic norm was valid due to: - system-membership (eg we in our society are part of a system) bindingness (this had to be an attribute of the basic norm) 4 when there is a revolution, OLD LAWS STOP BEING ENFORCED new laws by the rebels are enforced instead therefore, there is a NEW BASIC NORM authorising revolutionary constitution. (Might is Right notion) Critics say: do we really measure legality by effectiveness? (ie the more radical the coup the more lawful/authorised it is?) Kelsen – efficacy or effectiveness = pre-condition of legal validity (desirability, ethics or morality nothing to do with it) See McCoubrey re impact and understanding of grundnorm concept upon sovereign states agreeing to create and abide by ‘International Law’. *** Having studied the features of law – is international law actually “law”? What are its characteristics? At a philosophical level: Aspects which can be seen in a domestic context: the existence of obligation, external or internal, are arguably present: analysis can be the same, that it is obeyed, or should be obeyed because of arguments re attributes of one or some of the others: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Coercion (Bentham, Austin) (Law = Command of sovereign backed up by sanction) Social Contract (Socrates, Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau) Natural Law (Aquinas, Finnis, Fuller, Grotius) Integrity (Associative obligations, Individual Moral Integrity) (Dworkins) No obligation (The Razian analysis) Hallmarks which arguably make it resemble law as a practical matter: Logical, formal body of written, codified law Institutions have been set up to create and enforce it – Legislature, Courts (eg ICJ) Member states affected by it agree to be governed by it Enforcement sometimes is effective BUT: Absence of an international legislature Absence of courts with compulsory adjudication Absence of centrally organised sanctions Problems of jurisdiction The obligations of international law are different in character from those of national laws 5 John Austin (positivist), following Hobbes, Kant and Rousseau denies the existence of genuine international law Argument: All that exists is international customary morality Without a sovereign to enforce it, law does not exist. International law is therefore only law by ‘remote analogy’. Who is the sovereign? The United Nations? And then, even within the UN:(The General Assembly? The Security Council?) The United States? Enforcement? ICJ? Jurisdiction of The International Court of Justice - world court, judicial organ of UN. Dual jurisdiction (NB issues determination btw states, not justice in relation to individuals) Dispute resolution - Decisions on submitted disputes (in accordance with international law) by States; Advisory opinions - legal questions at the request of the organs of the United Nations or authorised agencies . ICC? International Criminal Court (ICC), governed by treaty – ‘Rome Statute’ (1 July 2002) 111 nation-states have ratified as at 2010 Non-UN – is first permanent, treaty based, international criminal court (for perpetrators of most serious crimes of concern to the international community.) ** Some theorists suggest that international law only gives rise to self-imposed obligation This is rather like the ‘social contract model’ Some of the problems which this gives rise to… Philosophers beginning with Hobbes have started out from the assumption of self-interested individuals pursuing their own goals (without a covenant with the state enforced by the sword, the life of man would be? Solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short’)! However, this leads to the following problem: Most efficient way to pursue one’s goals is either force or fraud Therefore left to its own devices society would degenerate into the ‘war of each against all’ The solution Hobbes proposes is that individuals agree voluntarily to restrict their selfinterest in pursuit of the common good. Without some pre-existing framework of rules and institutions, then self-imposed obligations would lack an obligatory character. 6 Further, the notion of tacit agreement fails to deal with the fact that new states are bound by international law which they had no stake in formulating Nuremberg Trials Along with the Tokyo trials, the Nuremberg tribunals are at the cornerstone of modern international law. Stalin proposed summary execution of some of German General Staff Both Churchill and Roosevelt initially supported summary execution of perpetrators From the outset, however, the legality of the trials was subject to question YES Argument Germany was acting in clear violation of a number of international treaties Germany’s actions were in clear violation of international customary law The Nuremberg tribunal was merely the mechanism for enforcing international law NO Argument The charges were ex-post facto (retrospective law? Critics using Fuller’s own paradigm – retroactive law leads to failure of system) The allies were also guilty of war crimes- Hiroshima, Dresden, Katyn…. Rules to suit victors Examples of International Bodies United Nations Council of Europe World Trade Organization Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development NATO European Union the four Geneva Conventions 1949; the two Additional Protocols 1977; the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees 1951; the Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees 1966. What is International Humanitarian Law? / Law of Armed Conflict Found in : Geneva Conventions Hague Conventions (1899, 1907) Other treaties Case Law Customary International Law Geneva Conventions: 1864, 1906, 1929, 1949... 7 First Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field" (first adopted in 1864, last revision in 1949) Second Geneva Convention "for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea" (first adopted in 1906) Third Geneva Convention "relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War" (first adopted in 1929, last revision in 1949) Fourth Geneva Convention "relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War" (first adopted in 1949, based on parts of the 1907 Hague Convention IV) Three additional amendment protocols to the Geneva Convention: Protocol I (1977): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts. As of 12 January 2007 ratified by 167 countries. Protocol II (1977): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts. As of 12 January 2007 by 163 countries. Protocol III (2005): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem. As of June 2007 ratified by 17 countries and signed but not yet ratified by an additional 68 countries. Hague and Geneva: both are branches of jus in bello, international law regarding acceptable practices while engaged in war and armed conflict. Some References: Peter Bailey – The Human Rights Enterprise in Australia and Internationally, 1st Edition, 2009 Sam Blay, Ryszard Piotrowicz, Martin Tsamenyi – Public International Law – An Australian Perspective 2nd Edition Gretchen Kewley - Humanitarian Law in Human Conflicts Stuart Kaye – Freedom of Navigation in Indo-Pacific Region – Papers in Australian Maritime Affairs No 22 *I.C.R.C. Handbook of the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement (1994). *Dieter Fleck (ed) The Handbook of Humanitarian Law in Armed Conflicts (1995). *I.C.R.C Bibliography of International Humanitarian Law Applicable in Armed Conflicts (1987). *Hilaire McCoubrey International Humanitarian Law: The Regulation of Armed Conflicts (1990) *Hilaire McCoubrey International Humanitarian Law: Modern Developments in the Limitation of Warfare (2nd ed, 1998). *Henry Dunant Institute International Dimensions of Humanitarian Law (1988). *H Durham and T McCormack (eds) The Changing Face of Conflict and the Efficacy of International Humanitarian Law (1999). 8 *Karine Lescure International Justice for Former Yugoslavia: The Working of the International Criminal Tribunal of the Hague (1996). *R Provost International Human Rights and Humanitarian Law (2002). N Ronzitti (ed) The Law of Naval Warfare (1988). Useful Websites International Committee of the Red Cross http://www.icrc.org United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees http://www.unhcr.ch United Nations http://www.un.org United Nations Treaty Database http://www.un.org/Depts/Treaty United Nations Law of the Sea http://www.un.org/Depts/los/index.htm International Criminal Court http://www.icc-cpi.int/menus/icc 1. 2. 3. 4. THE UNDHR is sometimes criticised on the following grounds: Systematic Vagueness Conflict of Rights Cultural Relativity Enforceability What is a ‘just war’? jus ad bellum - the right to go to war References: Cicero St Thomas Aquinas Hugo Grotius (1625 work - On the Laws of War and Peace - natural laws, independent of any individual state's legal system, apparent to human reason and should prevail - even during hostilities) the suffering inflicted by the aggressor [on the nation or community of nations] must be lasting, grave, and certain; all other means of putting an end to it must have been shown to be ineffective; there must be serious prospects of success; the use of arms [especially considering power of means/weapons of mass destruction] must not produce evils and disorders graver than the evil to be eliminated. 9 jus in bello - right conduct within war – distinction (combatants), proportionality, military necessity jus post bellum - justice after a war - peace treaties, reconstruction, war crimes trials, war reparations. (Reference: Louis V. Iasiello - former Rear Admiral in the US Navy.Naval War College Review (Summer/Fall 04): Jus Post Bellum: Moral Obligations of the Victors of War) What is the Law of the Sea? In summary: The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), International agreement following UNCLOS III (1973 – 1982) (Replaced 4 x 1958 treaties) The Law of the Sea Convention defines: rights and responsibilities of member states (nations) in: use of the world's oceans guidelines: for businesses, the environment, management of marine natural resources etc Philosophical conceptualisation - from Hugo Grotius. ***