What Is Fiscal Policy

advertisement

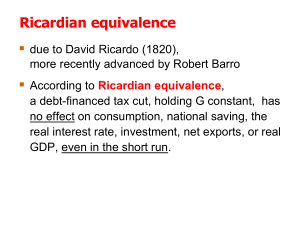

What Is Fiscal Policy Fiscal policy is the economic term which describes the actions of a government in setting the level of public expenditure and how that expenditure is funded. It contrasts with monetary policy, which describes the policies about interest rates setting and supply of money to the economy. Method of Raising Funds Governments spend money on a wide variety of things, from the military and police to services like education and healthcare, as well as transfer payments such as welfare benefits. This expenditure can be funded in a number of different ways: • Taxation of the population • Seignorage, the benefit from printing money • Borrowing money from the population, resulting in a fiscal deficit. Funding of deficits A fiscal deficit is often funded by issuing bonds, like Treasury bills or consols. These pay interest, either for a fixed period or indefinitely. If the interest and capital repayments are too great, a nation may default on its debts, most usually to foreign debtors. Economic effects of fiscal policy Governments often use their fiscal policy to try to influence the economy towards economic objectives such as low inflation and unemployment. According to Keynesian economics, high government spending, funded by a deficit, can be beneficial to the economy by stimulating aggregate demand and decreasing unemployment, during a recession. A corollary of this is that, during a period of inflation, a reduced deficit (or a budget surplus), can reduce inflation by reducing aggregate demand. This is a result of the Phillips curve, which describes the link between inflation and output/unemployment. The nature of fiscal policy has other economic effects, which are emphasised by other schools of economic thought. In particular: • Government borrowing is held to reduce private-sector borrowing and investment because of crowding out. • The linkage between deficits and inflation via the Phillips curve is controversial • Ricardian equivalence suggests that, since any fiscal deficit must ultimately be repaid, government borrowing will not affect the economy. All these factors suggest that the long-run effect of borrowing is much less beneficial than the short-run effect. To stop governments over-borrowing to meet short-term objectives, some nations have adopted fiscal policy rules, like the Golden Rule and the Stability and Growth Pact. Golden Rule The Golden Rule is a fiscal rule adopted by Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown for HM Treasury in the UK to provide a guideline for the operation of fiscal policy. The Golden Rule states that over the economic cycle, the Government will borrow only to invest and not to fund current spending. The justification for the Golden Rule derives from macroeconomic theory. Other things being equal, an increase in government borrowing raises the real interest rate consequently crowding out (reducing) investment because a higher rate of return is required for investment to be profitable. Unless the government uses the borrowed funds to invest in projects with a similar rate of return to private investment, capital accumulation falls, with negative consequences upon economic growth. The Stability and Growth Pact The Stability and Growth Pact is an agreement by European Union member states related to their conduct of fiscal policy, to facilitate and maintain Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union. It is based on Articles 99 and 104 of the European Community Treaty (with the amendments adopted in 1993 in Maastricht), and related decisions. It consists of enforcement policies of mutual surveillance of fiscal positions and of an excessive deficit procedure defined in the treaty. The pact was adopted in 1997 so that fiscal discipline would be maintained and enforced in the EMU. Member states adopting the euro have to meet the strict Maastricht convergence criteria. The actual criteria that member states must respect: An annual budget deficit no higher than 3% of GDP A public debt lower than 60% of GDP or approaching that value Future negotiations are likely to concentrate on the mechanisms of the Excessive Deficit Procedure, which is where the broad aspirations of the Treaty text are realized. Ricardian equivalence Ricardian equivalence, or the Barro-Ricardo equivalence proposition, is an economic theory which suggests that government budget deficits do not affect the total level of demand in an economy. It was proposed by the 19th century economist David Ricardo (April 18, 1772 – September 11, 1823). In simple terms, the theory can be described as follows. Governments may either finance their spending by taxing current taxpayers, or they may borrow money. However, they must eventually repay this borrowing by raising taxes above what they would otherwise have been in future. The choice is therefore between "tax now" and "tax later". Suppose that the government finances some extra spending through deficits - i.e. tax later. Ricardo argued that although taxpayers would have more money now, they would realize that they would have to pay higher tax in future and therefore save the extra money in order to pay the future tax. The extra saving by consumers would exactly offset the extra spending by government, so overall demand would remain unchanged. More recently, economists such as Robert Barro have developed more sophisticated variations on the same idea, particularly using the theory of rational expectations. Ricardian Equivalence suggests that government attempts to influence demand using fiscal policy will prove fruitless. It can be contrasted with alternative theories in Keynesian economics. In Keynesian models, a multiplier effect means that fiscal policy, far from being impotent, has a geared effect on demand, with a one pound increase in deficit spending increasing demand by more than one pound. Assumptions of Ricardian Equivalence Ricardian equivalence states that the level of government deficit does not affect the level of consumption. This is because people know that their taxes will have to rise in future to pay off the deficit, and so they save money now to pay off the future taxes. To work, this needs several conditions, most commonly: A perfect capital market where any household can borrow or save as much as is required. Intergenerational concern. The tax rise required may not occur for centuries, and will be paid off by the great-great-grandchildren of the population around at the time the debt was incurred. Ricardian equivalence only happens when the current generation has some concern for all future generations, even if not perfect concern. Barro phrased this as "any operative intergenerational transfer". These assumptions are widely challenged. The perfect capital market hypothesis is often held up for particular criticism because of the existence of liquidity constraints which invalidate the lifetime income hypothesis which it is based on. The existence of international capital markets also complicates the picture. However, the underlying intuition of the Barro-Ricardo model is that individual action can unravel Government policy, that the economy does not act in a mechanistic manner, and that policies can have unintended consequences. This is a key point of modern macroeconomic policy.