CHAPTER 6 - SOEST - University of Hawaii

advertisement

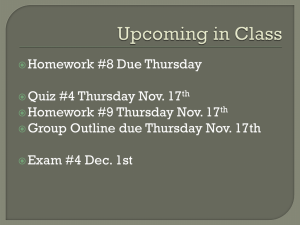

CHAPTER 6 HAWAIIAN FISHERIES The commercial fisheries industry is a very small factor in the economy of the state of Hawaii. Tourism is by far the most important economic driver in the state and presently accounts for more than $10 billion per year in direct income. For comparison, the commercial fish catch currently has an ex-vessel value of $50-$60 million, and the entire industry, including processing and retail, probably accounts for less than 1% of the state gross product. In terms of jobs, there are roughly 3,500 licensed commercial fishermen in Hawaii. However, it is likely that fewer than 500 of those persons work full-time at fishing (Anonymous, 1992). Commercial fishermen are far outnumbered by recreational anglers, who are estimated to number in excess of 250,000 persons (Glazier, 1999). Historically commercial fishing has been identified with first generation immigrants who may have had a tradition of fishing and who found themselves in an economic position unfavorable enough to make them willing to pursue what is acknowledged to be a risky and arduous livelihood (Anonymous, 1979). Quantitative information on the commercial fish catch extends back to 1948. Pelagic fish, particularly tuna and marlin, have dominated the commercial catch both by weight and by value for many years. Several developments have had major impacts on the contribution of the pelagic catch to the industry. First, passage by Congress of the Fishery Management and Conservation Act (FMCA or, as later amended, the Magnuson-Stevens Act) in 1976 established 200-mile fishery conservation zones around all U.S. coastlines. The FMCA, which became effective on March 1, 1977, also established Regional Fishery Management Councils comprised of federal and state officials to manage the stocks of fish within the fishery conservation zones. In the case of the Hawaiian Islands, implementation of the FMCA is the responsibility of the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council (WESPAC).1 As a part of its mandate, WESPAC has prepared fisheries management plans covering bottomfish, coral reef ecosystems, crustaceans, pelagics, and precious corals. 1 WESPAC is also responsible for management of the fishery resources around American Samoa, Guam, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, and U.S. Pacific island possessions. 1 Two aspects of the FCMA are of special importance. First, the FCMA gave the U.S. the authority to exclude foreign fishing boats from its fishery conservation zones.2 Prior to passage of the FCMA, foreign fishing boats could fish to within 12 miles of the U.S. coastline, and almost all of the Hawaiian commercial fish catch was taken within 20 miles of the main islands (Anonymous, 1979). After passage of the FCMA, the U.S. had complete control over the management of fish stocks within 200 miles of its coastline, and at least some Hawaii-based fishing vessels began fishing to the limits of the fishery conservation zone and beyond. The United States allowed Japanese longliners to continue to take tuna and billfish within the fishery conservation zone of the Hawaiian Islands until 1980, and reported catches by that fleet ranged between 1,300 and 5,000 tonnes per year. Until 1993 there was also a Japanese pole-and-line fishery for tuna in the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, but that was the only foreign fishing fleet operating legally within the Hawaii fishery conservation zone after 1980. Since 1993 all commercial fishing within the Hawaii fishery conservation zone has been done by vessels registered in the United States. An important caveat with respect to management has been the fact that highly migratory species such as tuna could be managed by the U.S. only during the time when they were within the U.S. fishery conservation zone. Recognizing this problem, in 1990 Congress amended the FCMA to acknowledge the need for international cooperation in the management of such highly migratory species. The Act now reads as follows: “The United States shall cooperate directly or through appropriate international organizations with those nations involved in fisheries for highly migratory species with a view to ensuring conservation and shall promote the achievement of optimum yield of such species throughout their range, both within and beyond the exclusive economic zone.” A second important development in the history of commercial fishing in Hawaii was the closure of the Hawaiian Tuna Packers (Bumble Bee Brand) cannery in Honolulu in 1984. Prior to that time the skipjack tuna fishery had sold its excess catch to the cannery. With the closure of the cannery, the only market for the skipjack fleet was the fresh fish market. This was a serious 2 The Act does not require the U.S. to exclude foreign fishing boats from fishery conservation zones. In fact, the Act states that it is the policy of Congress “to permit foreign fishing consistent with the provisions of this Act”. In practice, however, the U.S. has frequently chosen to exclude foreign fishing boats in order to preserve the resource for U.S. fishermen. 2 blow to the skipjack fishery, which until that time had been the mainstay of the Hawaiian commercial fishing industry. A third important development was the arrival in 1987 of longline fishing vessels from the U.S. mainland. The ships in question introduced modified gear and techniques targeting bigeye tuna and swordfish (Anonymous, 1992). The number of longline vessels increased rapidly over the next few years and has remained stable at 110-120 since 1990. The result was an almost step-function like increase in commercial landings and the value of the commercial catch during the late 1980s (Fig. 6.1). Figure 6.1. Hawaiian commercial fish catch by weight (A) and by ex-vessel value (B). A fourth important development was the discovery that the swordfish longline fishery was inadvertently catching endangered sea turtles. Between 1994 and 1999 swordfish longliners were estimated to have caught 112 leatherback turtles, of which nine died, and 418 loggerhead 3 turtles, of which 73 died. The result was a court-ordered moratorium on longline fishing techniques that targeted swordfish and an April-May closure of a large area of the Pacific between Hawaii and the equator to tuna longlining.3 The moratorium took effect in 2001. However, in March, 2004 the swordfish longline fishery was reopened and the April-May closure of tuna longlining south of the Hawaiian Islands was lifted, with the caveat that the swordfish fishery will be closed for the remainder of the year if a total of either 16 leatherback turtles or 17 loggerhead turtles are hooked, even if the turtles survive. In addition to concern over the turtle bycatch, there is also a problem with albatross, which are attracted to the same bait intended to catch swordfish (Anonymous, 2004). A final development with, at the moment, somewhat unclear implications for commercial fishing was President Clinton’s December 2000 executive order setting aside 340,000 km2 of ocean around the northwestern Hawaiian Islands as a coral reef ecosystem reserve, the largest protected area ever established in the United States. There is currently an effort underway to designate the reserve a national marine sanctuary under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act. At least some persons believe that commercial fishing should be banned within the reserve to protect the coral reef ecosystem. As things stand, WESPAC will be given an opportunity to prepare draft sanctuary regulations for fishing within the fishery conservation zone to the extent that such regulations are deemed necessary to implement the proposed sanctuary designation. The draft regulations will be guided by the FCMA to the extent that the FCMA standards are consistent and compatible with the goals and objectives of the proposed sanctuary designation. Skipjack tuna fishery The traditional skipjack tuna (aku) fishery around the Hawaiian Islands has been based on chumming with live baitfish, usually the Hawaiian anchovy or nehu. The nehu were typically obtained from either Kaneohe Bay or Pearl Harbor, and the availability of nehu and the ability of the fishermen to keep the bait alive in the bait wells was always a factor limiting the development of this fishery. Fishermen typically spend as much time catching bait as they do harvesting tuna. Fishing trips seldom exceed one day, but a work day is long and arduous. The 3 Longlining for swordfish appears to have a greater impact on sea turtles than longlining for tuna because the hooks that target swordfish are shallower in the water. 4 work begins in the early morning with the fishermen looking for bait. The aku boat, typically a wooden-hulled, sampan-type vessel, then heads out to see, looking for the flocks of birds that are associated with schools of skipjack tuna. Once a school has been located, the chum are used to lure the fish to the surface and induce a feeding frenzy. The fish are caught using bamboo pools and barbless hooks. The catch are iced in the baitwells. Between 1948 and 1980 reported aku landings varied in a random manner between roughly 2,500 and 7,500 tonnes y-1. Catches have been steadily declining since 1980 (Fig. 6.2). Several factors have contributed to the demise of the fishery. First, as noted in the 1985 Fisheries Development Plan (Anonymous, 1985, p. 68), “It is difficult to attract young local men to the fishery because of the long hours, arduous labor, and low pay.” From a peak of 32 aku vessels in 1948, the size of the aku fleet declined to 12 in 1984 and to five in 1992. There are currently two full-time aku boats. Another five fish part-time. As noted, the closure of the tuna cannery in 1984 was a major blow to the skipjack tuna fishery, but the pole-and-line fishery was already in decline by that time. Figure 6.2. Commercial landings of skipjack tuna. 5 Pelagic fisheries In addition to the aku pole-and-line fishery, the Hawaiian pelagic fishery has for many years included troll and handline components. The principal species taken by the troll fishery have included yellowfin and skipjack tuna, blue marlin, wahoo (ono), and mahimahi. Small quantities of bigeye and albacore tuna are also taken by the troll fishery. Most of the catch occurs within about 30 km of the main Hawaiian Islands. Handline fishing may be likened in some respects to flying a kite. The line is attached to a grip that can be held in the hand, and the line is baited with an artificial lure, small fish, or squid. The handline fishery has traditionally been based in Hilo and generally targets tuna, primarily yellowfin (ahi) and secondarily albacore. Some bigeye and skipjack tuna are also caught by handlining. A night handline fishery known as ika-shibi involves the use of lights to attract squid, which are then used as bait to catch ahi. Another variation known as palu ahi involves the release of mashed chum (palu) at the fishing depth of the hook. Figure 6.3 summarizes recent catches from the major species taken by the troll and handline fisheries. All catches have increased since 1980, with wahoo and mahimahi showing the greatest percent increases. At the present time by far the most important pelagic fishery is the longline fishery. In the case of the fishery targeting tuna, the fishing gear consists of a main line up to 100 km long, supported at regular intervals by vertical float lines. As many as 25 branch lines ending in a single, baited hook are attached to the main line between each pair of floats. The depth of the baited hooks effectively determines the species of fish targeted by the gear. One longline set is made per day, and traditionally the gear has been set so that it fished primarily during daylight hours. However, for long main lines deployment and retrieval may take almost 24 hours. The bait typically consists of scad, squid, sardines, anchovies, or saury. The longline fishery targeting swordfish differs in several respects. Much of the fishing occurs north of the Hawaiian Islands, and trips are 1-2 months in length. The main line is typically 50-60 kilometers long and is usually set in the evening and retrieved the following morning. As many as 800-1,000 baited branch lines baited are attached to the main line.4 4 Traditionally the bait has been squid, but recently mackerel-type bait has been mandated to reduce turtle interactions. 6 Interestingly, when the line is set to specifically target swordfish, sharks account for about half the catch and swordfish only one-third. Tuna and mahimahi make up most of the remainder of the catch. Figure 6.3. Commercial landings of wahoo, mahimahi, blue marlin, and yellowfin tuna. Catches of the principal species targeted by the longline fishery are shown in Fig. 6.4. In all cases, the catches were relatively insignificant prior to about 1987, when longliners first began to arrive in significant numbers from the mainland. Swordfish catches declined in the mid 1990s as the swordfishing fleet began to shift its attention toward tuna and then plummeted in 2001 as a result of restrictions resulting from concern over the turtle bycatch (see above). The decline in albacore catches at the same time suggests that significant numbers of albacore were being taken as part of the swordfish bycatch. Virtually all the swordfish catch is exported to the mainland. 7 Figure 6.4. Catches of the principal species targeted by the Hawaii longline fishery. One of the species taken in the bycatch of the tuna longline fishery is the pomfret or monchong. Like the other fish shown in Fig. 6.4, catches of pomfret were utterly insignificant prior to 1987. It is marketed fresh in local restaurants. In recent years catches of pomfret have been in excess of 200 tonnes y-1. Coastal Fisheries The coastal fisheries can be subdivided between pelagic and bottom fish. The bottom fish include several common table fish, including Opakapaka (crimson snapper or Hawaiian pink snapper), Onaga (ruby snapper or long-tailed snapper), Uku (grey snapper), and Kahala (amberjack). Fishing for these species is typically conducted at depths of 50-300 meters. The 8 principal bottom fishing ground is in the main Hawaiian Islands, where in recent years an average of nine vessels have been bringing in a catch of about 270 tonnes worth almost $2 million per year. The secondary bottom fishing grounds are in the northwest Hawaiian Island chain, the Hoomalu Zone and the Mau Zone (Fig. 6.5). Fishing in the Hoomalu and Mau zones is conducted solely by commercial fishermen and requires federal licensing. The Hoomalu Zone is a limited entry zone. In recent years commercial catches from these two areas combined have averaged 160 tonnes with a value of roughly $1.1 million per year. Fogure 6.5. Exclusive economic zones (fishery conservation zones) in the Pacific, including the Hoomalu and Mau bottom fishing zones in the northwest Hawaiian Islands. 9 Most bottom fishing around the Hawaiian Islands is carried out by vertical hook-and-line gear. Small fish that migrate into relatively shallow depths are occasionally trapped. Uku have sometimes been caught with special longline rigs. Figure 6.6. Commercial catches of four important bottom fish. Of the bottom fish, opakapaka has historically been the most important in terms of landed weight and value. It was one of the most common fish served in Hawaiian restaurants prior to World War II. However, during the last two decades, catches of opakapaka have been steadily declining. Based on analysis of catch per unit effort data, the NMFS has concluded that both Opakapaka and Onaga are recruitment overfished, and Uku are not far behind. Kahala catches have likewise been declining, but perhaps for reasons unrelated to overfishing. Kahala have the dubious distinction of being one of the few Hawaiian fish to be repeatedly implicated in cases of ciguateric fish poisoning, and consumption of individuals weighing more than about 9 kg is 10 generally considered inadvisable. Overall catches of bottom fish peaked in 1988, when there was a bonanza harvest of Uku. Since that time, catches have been steadily declining. Of the coastal pelagic catch, Akule (big-eyed scad) and Opelu (mackerel scad) are by far the most important. Both are small members of the jack family (Carangidae). They are caught with either nets or hand lines from the shore to a distance of about 5 km from the coastline. The market for Akule and Opelu includes human consumption (fresh, dried, smoked, and sometimes raw) and bait for tuna. Commercial catches of both Akule and Opelu have been relatively stable in recent years (Fig. 6.7), and at least for the time being, the stocks appear to be in good shape. Figure 6.7. Commercial catches of Akule and Opelu. 11 Lobster Fishery The Hawaiian lobster fishery is a more-or-less classic case of boom and bust. There are two principal species involved in the fishery, the spiny lobster and the slipper lobster. Research cruises conducted in 1976 documented the existence of stocks of both species in the northwest Hawaiian Islands, and commercial trapping began in 1977. The traps used in the fishery are dome-shaped molded polyethylene with a mesh size of 45 by 45 mm. Each trap has two entrance cones on opposite sides. There are also vent panels to facilitate the escape of lobsters below the minimum size limit. The traps are typically baited with chopped mackerel and fished in strings of several hundred traps. The history of the commercial lobster catch is shown in Fig. 6.8. During most of the history of the fishery catches have been dominated by spiny lobsters. For the first few years catches were relatively low, but they began to increase rapidly during the mid 1980s as more vessels entered the fishery and markets were developed. After only a few years catches were on the decline. The stocks were unable to withstand the fishing pressure. The fishery was completely shut down in 1993, and there was an emergency closure after the fishery started up again in 1994. In 1995 a single vessel was allowed to catch lobsters with an experimental permit and a very restricted quota. The fishery was opened with a small quota in 1996 and a somewhat larger quota in 1997. However, by this time more than overfishing was at issue. Evidence was accumulating to suggest that the lobsters were an important component of the diet of Hawaiian Monk Seals, an endangered species. In 1997 a NMFS report noted that monk seal populations at French Frigate Shoals had declined by 55% since 1989 and that pup survival had dropped from 90% to 10%. In 1999 the Marine Mammal Commission sent a letter to the NMFS recommending a closure of lobster fishing at all major monk seal breeding atolls. In 2000 WESPAC, following a recommendation by the NMFS, closed the lobster fishery at the three primary northwest Hawaiian Island banks (Necker, Maro, and Gardner) through 2001 and at all other banks through 2002. For all intents and purposes, the lobster fishery is now shut down. 12 Figure 6.8. History of commercial lobster catches. Economic Value The economic value of the most important components of the Hawaii commercial fish catch are summarized in Table 7.1 for the year 2003. In that year the ex-vessel value of the entire commercial catch was about $52.5 million. Bigeye tuna accounted for almost half the value of the catch, and tuna collectively accounted for more than 70% of the ex-vessel value. Bigeye tuna were worth more than three times as much per kilogram as skipjack tuna, but by far the most valuable species in the creel were Onaga and Opakapaka, which are prime table fish. 13 Table 7.1. Economic value of principal species in the Hawaiian fishery in 2003 Species Caught (tonnes) Sold (tonnes) Bigeye tuna 3809 3745 $6.88 $25,779,265 Yellowfin tuna 1551 1551 $5.56 $8,632,843 Mahimahi 595 595 $4.90 $2,913,731 Wahoo 451 445 $4.28 $1,902,953 Albacore 618 608 $2.56 $1,561,017 Skipjack tuna 719 604 $2.21 $1,331,504 Striped marlin 623 621 $1.85 $1,155,267 Blue marlin 502 432 $1.90 $823,172 Pomfret 210 208 $3.73 $776,855 Swordfish 154 150 $4.81 $721,440 Onaga 59 59 $12.24 $721,436 Opakapaka 63 62 $11.53 $711,396 Akule 196 148 $3.44 $508,316 Opelu 146 111 $4.26 $473,127 14 Price per kilogram Value References Anonymous, 1979. Hawaii Fisheries Development Plan (report prepared for Division of Aquatic Resources, DLNR, State of Hawaii), State of Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, Honolulu. Anonymous, 1985. Hawaii Fisheries Plan 1985 (report prepared for Division of Aquatic Resources, DLNR, State of Hawaii), State of Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources, Honolulu. Anonymous, 1992. Hawaii Fisheries Plan: 1990-1995 (report prepared for Division of Aquatic Resources, DLNR, State of Hawaii), LMR Fisheries Research, San Diego. Anonymous, 2004. Draft environmental impact statement: Seabird interaction mitigation methods. NOAA Fisheries Pacific Islands Regional Office. http://swr.nmfs.noaa.gov/pir/draft/deis.htm. Glazier, E. W., 1999. Non-Commercial Fisheries in the Central and Western Pacific: A Summary Review of the Literature. Pelagic Fisheries Research Program, University of Hawaii Joint Institute of Marine and Atmospheric Research, Honolulu. 15