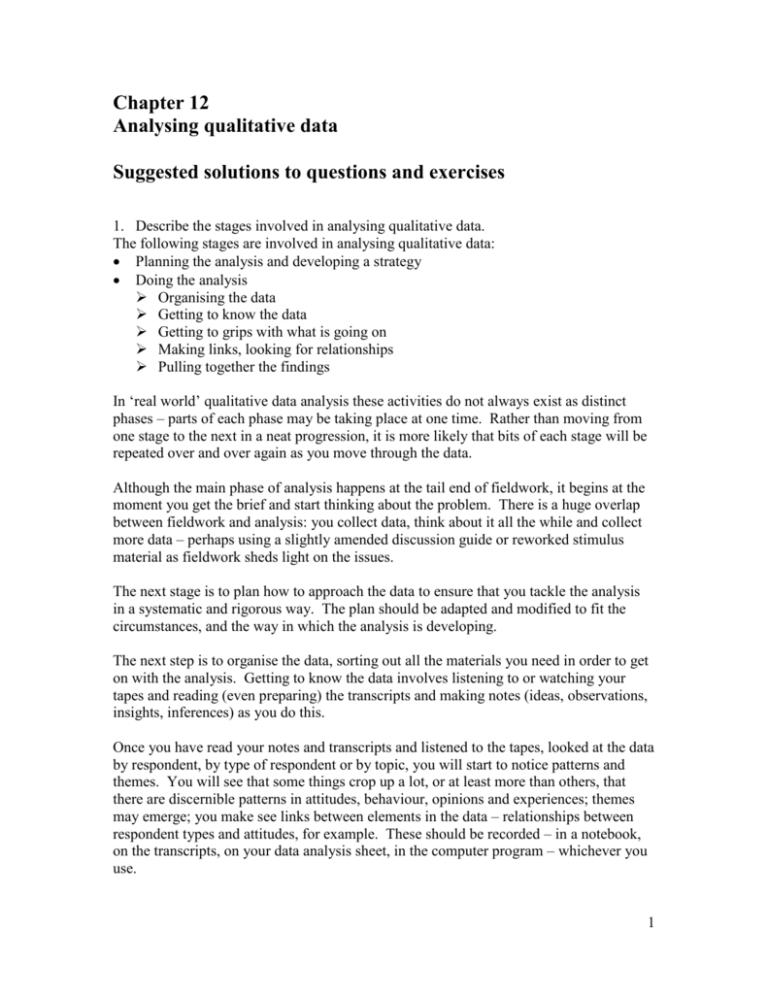

Analysing qualitative data

advertisement

Chapter 12 Analysing qualitative data Suggested solutions to questions and exercises 1. Describe the stages involved in analysing qualitative data. The following stages are involved in analysing qualitative data: Planning the analysis and developing a strategy Doing the analysis Organising the data Getting to know the data Getting to grips with what is going on Making links, looking for relationships Pulling together the findings In ‘real world’ qualitative data analysis these activities do not always exist as distinct phases – parts of each phase may be taking place at one time. Rather than moving from one stage to the next in a neat progression, it is more likely that bits of each stage will be repeated over and over again as you move through the data. Although the main phase of analysis happens at the tail end of fieldwork, it begins at the moment you get the brief and start thinking about the problem. There is a huge overlap between fieldwork and analysis: you collect data, think about it all the while and collect more data – perhaps using a slightly amended discussion guide or reworked stimulus material as fieldwork sheds light on the issues. The next stage is to plan how to approach the data to ensure that you tackle the analysis in a systematic and rigorous way. The plan should be adapted and modified to fit the circumstances, and the way in which the analysis is developing. The next step is to organise the data, sorting out all the materials you need in order to get on with the analysis. Getting to know the data involves listening to or watching your tapes and reading (even preparing) the transcripts and making notes (ideas, observations, insights, inferences) as you do this. Once you have read your notes and transcripts and listened to the tapes, looked at the data by respondent, by type of respondent or by topic, you will start to notice patterns and themes. You will see that some things crop up a lot, or at least more than others, that there are discernible patterns in attitudes, behaviour, opinions and experiences; themes may emerge; you make see links between elements in the data – relationships between respondent types and attitudes, for example. These should be recorded – in a notebook, on the transcripts, on your data analysis sheet, in the computer program – whichever you use. 1 At this stage a ‘story’ should be emerging and it is likely that you will have some ideas or explanations about what is going on. The next step is to question these ideas, insights and explanations in the data, test them out to make sure that they stand up. It is important to look for alternative explanations, evidence to support the ideas and interpretations, to verify them, as well as evidence that might not support them. You may need to repeat several steps in the process. Working through the data in this thorough and systematic way should ensure that you will reach a point where suddenly it all seems to fit together and make sense – producing an argument or story that addresses the research objectives. 2. What is coding and why is it useful in analysis? To understand fully what is going on, you need to dissect the data, pull them apart and scrutinise them bit by bit. This involves working through the data, identifying themes and patterns and labelling them or placing them under headings or brief descriptions summarising what they mean. This process is known as categorising or coding the data. This coding process is not just a mechanical one of naming things and assigning them to categories, it is also a creative and analytic process involving dissecting and ordering the data in a meaningful way – a way that helps you think about and understand the research problem. Coding is a useful ‘data handling’ tool – by bringing similar bits of data together and by reducing them to summary codes you make the mass of data more manageable and easier to get to grips with, enabling you to see what is going on relatively quickly and easily. The process of developing codes and searching for examples, instances and occurrences of material that relate to the code ensures that you take a rigorous and systematic approach. Codes are also a useful ‘data thinking’ tool. The codes you develop – and the way you lay them out – allows you to see fairly quickly and easily what similarities, differences, patterns, themes, relationships and so on, exist in the data. They should lead you to question the data and what you see in them. The coding process can help you develop the bigger picture by bringing together material related to your ideas and hunches, thus enabling you to put a conceptual order on the data (moving from specific instances to general statements) and to make links and generate findings. The topics or question areas in the discussion or interview guide can be used as general codes or headings in the early stages of the analysis; as you work through the analysis process it is likely that codes (ideas) will emerge from the data. The coding process can also be tackled in a number of ways, and different researchers have different approaches, and may use different technologies – pen and paper or computer. A relatively easy way of doing it if transcripts are available in a word processing package is to create a new document for each heading, topic or code. As you work through the transcript cut out sections of text that relate to the code and paste them into the document you have created to represent that code. In this way you can build up a 2 store of relevant material related to that particular code or topic. It is important to label the source of each bit (respondent details, group, place in transcript) that you cut so that you know the context from which it came, and can refer back to it if necessary. It may be that one bit of data or text fits under more than one heading or code. You could, alternatively, go through the transcript and label bits of text in situ, before gathering the same or similarly labelled bits in one place or under one heading. Usually it is necessary to make several – at least two – coding ‘passes’ through the data. At first pass, the codes you devise may be fairly general. Keep the number to a minimum. As you work through the data a second time you can divide these big, general codes into more specific ones. Alternatively, you can code the other way round – coding everything that occurs to you as you pass through the data the first time and use the second or third pass to structure or revise these more detailed codes. There is no right or wrong way. 3. Why are tables, diagrams and maps useful in analysis. Give examples of their use. Using diagrams, tables, flow charts and maps to sort and present data can help you think and can help to uncover or elucidate patterns and relationships. Some people can think and/or express ideas better in pictures and diagrams than they can in words. Reducing data to fit a diagram or table can focus the thinking on the relationships that exist in the data. The most suitable format will depend largely on what it is you are trying to understand. A perceptual map may be useful in showing how different brands lie in relation to each other and key brand attributes; a flow chart can be a useful way of summarising the decision-making process in buying a car; a table can be useful in showing the responses of different sub-groups in the sample to a key question. 4. Describe the advantages and disadvantages of computer-aided qualitative data analysis. Computer-aided qualitative data analysis makes the mechanical aspects of data analysis – search and retrieval of text, cutting, pasting and coding – easier and more efficient. Some programs have mapping capabilities and some have functions which help in building theory – linking concepts and categories – which can speed the analysis process and make it more thorough and systematic. It allows an audit trail through the process, which is helpful for reviewing the analysis and interpretation of the data. Computer-aided analysis is particularly useful for large-scale qualitative projects. The main drawbacks are that the process is time-consuming – at least in the initial set up phase (and for newcomers – the learning curve for some programs can be steep) and it relies on full transcripts of the data being available. It is therefore not suitable for small projects involving, say, less than six groups or when deadlines are tight. 5. Prepare a checklist that you might use to assess the quality of a piece of data analysis. The following list of questions may be useful in checking the quality of a piece of data analysis: How plausible are the findings? Do they make sense? 3 4 Are they intuitive or counter-intuitive? Surprising or what you might expect? How much evidence is there to support them? How credible and plausible is this evidence? How does it fit with what you know of the issue/market/brand? How does it fit with evidence gathered elsewhere From other research in this area? From theory? Have alternative explanations or interpretations been presented? Do these other explanations fit the data better? Has the researcher been systematic and rigorous in looking for evidence and taking into account all views and perspectives? Are contradictions, oddities or outliers accounted for or explained? Has the researcher introduced any bias? Has he or she given more weight to what the more articulate in the sample have said at the expense of others? Is he or she seeing in the data what he or she wants to see? Has the researcher over-interpreted things? Gone too far beyond the data? Has anything been missed or overlooked?