Session 10.1a

advertisement

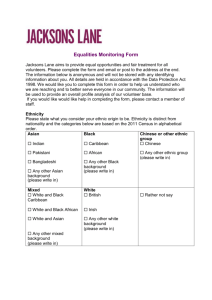

Session 10 John Hutchinson and Anthony Smith ed., Ethnicity, Oxford Readers, 1996, pp. 314, 32-51 and 85-98, 275-347 pp. 3-14, 32-51 and 85-98 I. Introduction (pp. 3-14) Main focus: political impact of ethnicity, and the impact of political conflicts on ethnic community and identity. Common ethnicity is a major focus of identification by individuals, supporting social integration and individual adaptation. Although ethnicity is often associated with conflict and political struggle, there is no necessary connection between ethnicity and conflict. Sources of conflict: struggle for scarce resources, economic inequalities superimposed on ranked ethnic groups (esp. during rapid industrialization), cultural (linguistic and religious) differences, distribution of political rewards in polyethnic states, ethnic movements of secession and irredentism. a. Ethnicity and ethnic identity: A relatively new term used to refer to others who belong to some group unlike one’s own. Ethnic identity/origin: individual level of identification with and belonging to a culturally defined collectivity. Ethnocentrism: disdain of the stranger or a sense of uniqueness/centrality of one own group as opposed to others. b. The concept of ethnie: A named human population with myths of common ancestry, shared historical memories, one or more elements of common culture (religion, customs, language), a link with homeland, and a sense of solidarity among at least some of its members. c. Approaches to ethnicity: Primordialists believe that the drive for an efficient state interacts with the other great drive for personal identity, which is based on primordial ties (religion, blood, race, language). Instrumentalists believe that ethnicity is a social, political or cultural resource for different interest and status groups; individuals can forge their own personal or group identities. Other approaches include: transactional, social psychological, and ethno-symbolic. d. Ethnicity in history: varied in importance throughout history, but present in all regions. e. Ethnicity in the modern world: In the modern rational state integration was expected; there was no room for ethnic autonomy. This did not happen. Ethnicity persists in the forms of: ethnic hybridization, multi-culturalism in pluralist states, diaspora communities and vicarious nationalism, ethnic divisions in post-colonial states, racism, etc. f. Transcending ethnicity: Two general options: Ethnicity fades and becomes a residual category when no other arguments work. No room for ethnic identities in advanced industrialism, nationalism, or globalization. Ethnicity grows due to advances in electronic communications and information technology, which provides ethnic groups with dense cultural networks in a post-industrial society. II. Theories of Ethnicity (pp. 32-104) Summary: The authors in this section duke it out over primordialism vs. intrumentalism. Greetz, the father primoridialist, says that ethnicity was, is and always will be. Eller/Coughan say that Geertz is stoopid and that ethnicity is not a given at all. Brass says “Primordial Schmimordial. Blame the elites, blame the leaders, blame the powerful” (hell, why not blame Canada?). Hechter tries to put the last nail in the primordialists’ coffin with his rational choice spiel. And finally, Weber, who is too 116103120 Page 1 of 3 German for me to understand, seems to be keeping everyone happy by sort of agreeing with both camps. A. Max Weber: The Origins of Ethnic Groups (pp. 35-40) Defines ethnic group as: human groups that entertain a subjective in their common descent because of similarities of physical and/or customs, or because of memories of colonization/migration. May or may not be objectively true. Ethnic membership does not constitute a group; it only facilitates group formation in the political sphere (objectivity leads to an instrumentalist interpretation). Yet at the same time, even after the end of the political purposes of group formation, a specific and powerful sense of ethnic identity can arise and persist. Determined by factors: conduct of everyday life, shared political memories, language, etc. Common customs derived largely from adaptation to natural conditions and imitation of neighbours (subjectivity leads to constructionist primordialism). A drive to political action is one of the major potentialities inherent in the notions of tribe and people. Can easily develop into the moral duty of all members of the tribe/people to military cooperation even if there is no corresponding political association. B. Clifford Greetz: Primordial Ties (pp. 40-45) New state citizens have to interdependent and competing motives: The personal desire to be recognized as a responsible agent within the state. Primordial identity and public recognition of that identity socially assert the self/group as “someone in the world.” ii. The practical desire to build an efficient, dynamic modern state that can raise standard of living, provide political stability, ensure social justice, and assert an international presence. The tension between these two desires is always present in the evolution of the modern state, but is especially severe in new states. In new states, people want the benefits that a modern state can bring, but fear loss of personal definition, absorption into a culturally undifferentiated mass, or domination by another group that controls the state. In modernizing states, civil politics are weak and bureaucratic capacity is low, this makes it easy for primordial groups to become the basis of autonomous political units. However, this is problematic in that ethnic groups cannot replace the state; they do not involve viable alternatives to the state. Primordial identity is based on: assumed blood ties, race, language region, religion, and custom. i. C. Jack Eller and Reed Coughlan: The Poverty of Primordialism (pp. 45-51) The authors set out to attack primordial understanding of ethnicity, as offered by Greetz). They identify three primordialist points (in italics below) and debunk each point: i. Ethnicity is a priori (underived, natural, have no social source). Ethnicity, however, is not selfperpetuating, but requires on-going creative effort and investment. Also, new ethnic groups were created under colonial rule, constructed in order to provide a political base for a group or introduce ethnic disputes. Supported by ‘compulsory ethnicity’ and ethnic mobilization. Ineffable, (coercive and un-analyzable). But ethnicity can be analyzed in terms of the circumstances that it comes out of. For example, when a group faces exclusion or comes under attack, ethnic feelings are generated. Ethnicity is elicited through experiences. Affective (based on strong emotions and sentimental attachments). By labelling ethnicity in this way, the primordialists mystify the emotions and desocialize the phenomena of ethnicity (therefore, ethnicity is explained biologically, not anthropologically). Although the emotional experience is genuine, it does not exist outside the sphere of insights that seek to account for the genesis of the emotions. Affective ties do not simply exist, but are the outcome of a relationship that can be discussed and analyzed (if not fully, at least partially). ii. iii. D. Paul R. Bass: Ethnic Groups and Ethnic Identity Formation (pp. 85-90) 116103120 Page 2 of 3 Three ways of defining ethnic groups: objective attributes (problem: difficult to define boundaries), subjective feelings (problem: whence ethnic self-consciousness in the first place?), or behaviour patterns (most appropriate, if acknowledged that these objective markers can shift and change). Ethnicity: is a sense of ethnic identity consisting of a subjective, symbolic or emblematic use by a group of any cultural aspect to create internal cohesion and differentiate themselves from other groups. Similar to class for social organization and identification purposes. Contingent and changeable (and therefore may not always be articulated). Can be used in political arenas to secure economic benefits, rights, status, or opportunities. Two stage process: i. Development of communities from ethnic categories. Some groups never make this transition (e.g., Cornish in the UK), others make the transition only in modern times (e.g., Naga in India), and others make it repeatedly over history (e.g., Jews, Han Chinese, major European nationalities). ii. Transformation of an ethnic community into a nationality. Occurs when ethnic groups articulate and acquire - through political action and mobilization - social, economic, and political rights for the group as a whole. Ethnicities display particular dialects, religious practices, styles of dress, and symbols. However, the transformation of ethnic categories into ethnic communities and nationalities is not predetermined by the group’s cultural heritage, language development, or religious belief distinctions. Ethnic communities are transformed by particular elites in modernizing and post-industrial societies that are undergoing dramatic social change. It does not occur when elites find it to their advantage to cooperate with external authorities and adopt the language/culture of the dominant ethnic group in order to maintain/enhance their own power. It does occur where there is conflict between indigenous and external elites and authorities, or between indigenous elites themselves. Four possible sources of elite conflict: i. Between local aristocracy attempting to maintain its privileges against an alien conqueror; ii. Between competing religious elites from different ethnic groups; iii. Between religious elites and the native aristocracy within an ethnic group; and iv. Between native religious elites and an alien aristocracy. E. Michael Hechter: Ethnicity and Rational Choice Theory (pp. 90-98) Previous methods for understanding ethnicity are normative (primordial) or structural (instrumental). The former is relatively static and cannot fully account for changes in behaviour. The latter does not account for role of individual preferences in group-formation. Rational choice offers the best method to explain and predict ethnic behaviour, linking structural constraints on one hand (macro-level) and preferences that motivate individual behaviour on the other (micro-level). Rational choice: individual behaviour is a function of the interaction between structural constraints and the sovereign preferences of individuals. Course of action ultimately chosen is rational and can be predicted with individual preferences are known, temporally stable, and transitive. Preferences will tend to choices that result in more wealth, power and honour. Weakness of rational choice is an inability to account for preference-formation (internal states and environmental constraints help individuals to determine their actions). Argues that preferences are transmitted through learning process and modeling, so that adaptive preferences are selected over maladaptive preferences. Persistence of most urban ethnic and racial minorities is often due to limitations of opportunities from outside group boundaries (i.e., forces that channel group members into distinctive positions in a cultural division of labour. 116103120 Page 3 of 3