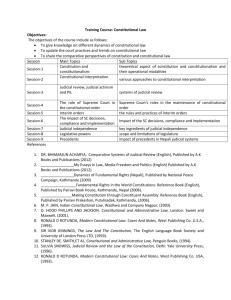

Constitutional Interpretation and the Notion of

advertisement