CURSE HEAVEN FOR LITTLE GIRLS

advertisement

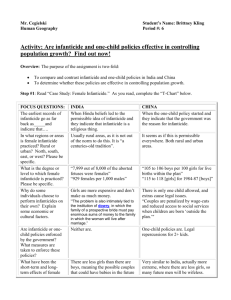

1 Curse Heaven for Little Girls from Time, January 4, 1988 1. Despite pain and exhaustion, a triumphant smile brightened Prem’s face. The 30-yearold mother had just given birth to her sixth child, which now nestled next to her in a small house on the outskirts of New Delhi. “I have had a son,” she whispered. “Finally,” said one of her relatives. Prem had already borne five daughters, yet with each pregnancy she had hoped for a boy. Now, visibly anemic and frail, she had at last earned the respect of her husband and family. “It is G-d’s grace,” said Prem’s motherin-law as she greeted guests who streamed into the house to congratulate the new parents. “He has finally listened to our prayers.” 2. Today, as in the past, the birth of a son is an occasion for celebration in many parts of Asia, while the arrival of a baby girl is often met with silence. Despite brisk economic and technological development, parts of Asia remain shackled by a patriarchal tradition, burdensome dowry systems, and social stigmas that combine to make girls less valued than boys. As a result, women can be deserted, divorced, or even beaten by their husbands if they fail to produce a male heir. “The pressure to have a son is tremendous on a woman, even among the educated,” says Madhu Kishwar, a founding member of Manushi (Womanhood), a New Delhi-based women’s organization. This bias against girls is as persistent in the Confucian societies of China and South Korea as it is in Islamic Pakistan and Malaysia and predominantly Hindu India. 3. It is one thing not to want a child because it is a girl and another to kill it because of its sex. Female infanticide – the killing of newborn girls – was once widespread in Asia. That is no longer the case. Government efforts to curb the practice have largely been successful except in some remote areas of China and India. The elimination of unwanted daughters continues, however, through the abortion of female fetuses. Prenatal sex-detection methods are widely used in Bombay, Seoul, and other big Asian cities. When prospective parents are told their child will be a girl, an abortion often follows. 4. The causes of female infanticide and feticide are primarily economic. In India a daughter is often described as a “bird of passage” or a “guest in her parents’ house.” Once she marries, a woman is expected to live with her husband’s family, performing household chores and caring for her in-laws. Not only do her parents lose her services, ____________________________________________________________________________ Curse Heaven for Little Girls 2 but they are usually expected to bear the full cost of the wedding as well as provide a dowry of cash and other gifts. A son, on the other hand, brings wealth – and another worker – into the family when he weds, and he perpetuates the family name and business. It is little wonder that mothers-to-be in India, South Korea, and other parts of Asia still pray for a male child. 5. In China peasants continue to rely on male children to till the family plot, haul water, feed the livestock and take care of the elderly, while daughters join their husbands’ families at marriage. After the Communist Revolution in 1949, female infanticide was officially banned, and its occurrence dropped sharply. But beginning in 1979, when Beijing introduced a one-child policy to control the nation’s burgeoning population, some rural Chinese resurrected the practice. 6. According to reports coming out of China in the early 1980’s, parents fed their newborn girls poison or strangled or drowned them in the hope that they could legally conceive again and have a male child. In the northeastern port city of Tianjin, a father bit off part of the nose of his eight-month-old daughter, so he could take advantage of a loophole permitting a couple to have a second child if the first is deformed. 7. The drive to have sons rather than daughters soon became apparent in a lopsided ratio of female and male newborns. According to demographers, for every 100 girls born in China in 1981 there were 108 boys, two more than the worldwide norm. Publication of these statistics sparked an international outcry, and for several years Chinese sex-ratio data were unavailable to Western researchers. 8. To combat what Chinese authorities describe as a “feudal vestige,” Beijing mounted a vigorous campaign against the killing of female newborns. The one-child policy was relaxed to allow families to have a second child after a four-to-seven year wait, provided there are “real difficulties.” Though designed for parents whose offspring are mentally or physically handicapped, this exemption is frequently invoked when the first child is a girl. Infanticide is considered a serious offense, and parents who attempt it are subjected not only to censure and scorn but also to imprisonment. In 1985 the story of Guo Shiqing, a carpenter from Kaifeng in Henan province who tried to kill his baby girl by sticking pins in her head, stomach, and buttocks, was widely featured in the Chinese press. He was eventually jailed. Says an aide to U.S. Congressman Jim Moody of Wisconsin, chairman of the Congressional Coalition on Population and Development, whose members and staff visited China in 1986: “We came away with ____________________________________________________________________________ Curse Heaven for Little Girls 3 the very firm sense that the Chinese are moving as toughly as they can to deal with the problem.” 9. The introduction of modern medical technology may thwart such efforts. Most major city hospitals offer amniocentesis and ultrasonography, procedures developed to detect birth defects in fetuses. The test can also determine, with varying degrees of accuracy, the gender of the unborn child. 10. To safeguard against female feticide, Chinese medical authorities in 1986 asked doctors who administer amniocentesis and ultrasonography to vow that they would not tell parents the sex of their unborn baby. However, compliance is difficult to monitor, and some parents still use guanx, or connections, to obtain the information. 11. In India the British colonial government banned the killing of female newborns in 1879. Today the Indian penal code prohibits it. As in China, infanticide occurs only in the most isolated villages. In urban areas, however, the use of amniocentesis, ultrasonography, and chorionic villi biopsy – another prenatal test used to spot genetic defects and determine gender – has led to the frequent abortion of female fetuses. In Maharashtra, a western state whose capital, Bombay, is India’s second largest city, the number of so-called sex-detection clinics performing amniocentesis has risen from ten in 1982 to more than 500 today. Virtually all prospective mothers who take the test, which can cost as little as 70 rupees ($5.38), are interested primarily in the gender of their unborn child, and clients come from all across the social spectrum. 12. Debate in India over the practice has been sharp, particularly between physicians and women’s groups. In 1986 feminists succeeded in getting posters advocating sexdetection procedures removed from Bombay’s buses and trains. That same year, Sharad Dighe, an M.P. and a member of the ruling Congress Party, introduced a bill in the Lok Sabha that would forbid abortions stemming from tests conducted solely to discern the sex of the fetus. No action has yet been taken on the proposal. Gender detection, says Dighe, is “a misuse of science and technology, social oppression of women, and an abuse of human rights.” 13. Many doctors and even some feminists disagree. “It isn’t right to impose an unwanted pregnancy on anyone,” says Ditta Pai, a physician and owner of the Pearl Center, a birth-control and abortion clinic in Bombay. “Until newly married couples are made to understand that they have to look after both the husband’s and the wife’s parents, male preference will remain." Concurs New Delhi feminist Kishwar: “People cannot be ____________________________________________________________________________ Curse Heaven for Little Girls 4 beaten into becoming more humane. Banning amniocentesis would only drive it underground, making it more expensive and unsafe, and making women’s lives harder.” 14. Until the overall status of women improves, attempts to stop the practice of killing females will probably have only limited success. There are signs, however, that change is beginning to take root. After years of campaigning by feminists, for example, South Korea in 1986 revised its family law to permit women to inherit property from their fathers and to become the legal heads of households. Until then only males enjoyed such rights, making the birth of a son necessary for carrying on the family name and wealth. 15. India now has a Department of Women and Child Development under the Ministry of Human Resources Development, which has been instrumental in introducing legislation to eradicate the dowry system as well as suttee, a ritual requiring a widow to immolate herself on her husband’s funeral pyre. The department has also initiated programs to persuade parents to educate their female children and train them for economic selfsufficiency. But the process of undoing centuries of cultural prejudice and patriarchal tradition is likely to take a while longer. ____________________________________________________________________________ Curse Heaven for Little Girls