fiv_acvim_2004

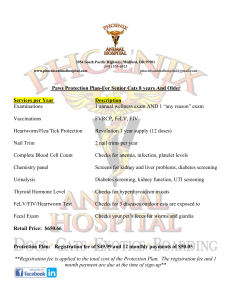

advertisement

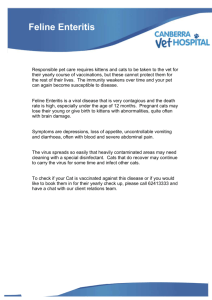

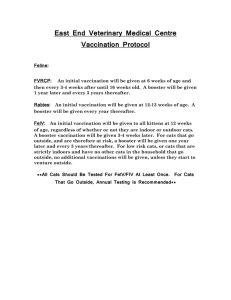

FIV: PREVENTION AND TREATMENT Julie Levy, DVM, PhD, DACVIM Gainesville, FL En PROC. 22nd ACVIM 18 MINNEAPOLIS, MN 2004 INTRODUCTION Feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) is a lymphotrophic lentivirus that, like HIV in humans, causes an acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) in domestic cats. FIV is related morphologically and biochemically to HIV but is antigenically distinct. Both viruses also share a similar pattern of pathogenesis, characterized by a long period of clinical latency during which immune function gradually deteriorates. Eventually, AIDS develops and is accompanied by opportunistic infections, systemic diseases, and malignancies. It is the close relationship between HIV and FIV that has kindled interest in the use of FIV as an animal model for the study of lentiviral immunopathogenesis. PATHOGENESIS Within the first few weeks of FIV infection, both CD4+ (helper T cells) and CD8+ (cytotoxic-suppressor T cells) cells decline. The initial lymphopenia is followed by a robust immune response, which is characterized by the production of FIV antibodies and a rebound in CD8+ cells above preinfection levels. This results in a persistent inversion of the CD4+:CD8+ ratio. Over time, both CD4+ and CD8+ cells gradually decline. In HIV, distinctive clinical stages can be defined based on absolute CD4+ cell count. A CD4+ cell count of ¡Ü200/µl is an AIDS-defining condition in HIV infection. It is more difficult to assignn clinical stages of disease to cats, because FIV appears to be less pathogenic than HIV. Although chronic inflammatory conditions and opportunistic infections are more common in cats with low CD4+ cells, other cats appear to remain healthy. It is generally recognized that cell-mediated immunity is more profoundly affected than humoral immunity. Chronic inflammatory conditions, neoplasia, and infections with intracellular organisms are more common than infections controlled by antibodies. FIV-infected cats appear to respond adequately to vaccination and frequently develop a polyclonal hypergammaglobulinemia characteristic of nonspecific stimulation of humoral immunity. VIRAL TRANSMISSION Although the existence of FIV was first reported in 1987, there are extensive data indicating that cats have carried the virus for a much longer time. FIV has a worldwide distribution in domestic cats, with infection rates approaching one third of the cats in some populations. Strains of viruses related to FIV are also found to infect at least 27 species of wild felidae. In the wild, it appears that a majority of lions are infected, but few clinical signs are apparent. The greater diversity of viral nucleic acid sequences and the decreased pathogenicity of wild cat strains compared with those that affect domestic cats suggest that nondomestic felids have been living with lentiviruses for a longer time and that the domestic cat strains may have emerged more recently from ancient nondomestic cat strains. This is reminiscent of the situation with HIV, which recently made a jump from a related minimally pathogenic virus in monkeys to humans, in whom the virus is much more virulent. Epidemiologic studies of domestic cats have long suggested that most cases of FIV infection are acquired by horizontaltransmission among adult cats. Worldwide, adult male cats living outdoors consistently compose the majority FIV-infected cats,and the risk is highest for sexually intact males. The fighting and biting behaviour of this group of cats is believed to be the main cause of transmission. Infectious virus is found in the saliva of FIV-positive cats, and the virus has been successfully transmitted via experimental bite wounds. Interestingly, sexual transmission, the most common mode of transmission of HIV, appears to be unusual in FIV, even though the semen of infected cats frequently contains infectious virus. In an interesting mathematical model of FIV transmission within colonies of free-roaming cats, it was suggested that FIV had little impact on the total population size and health. A low rate of transmission, the long asymptomatic stage of infection, and death from other causes combined to minimize the effect of the virus on feral cats. Such colonies existed at the carrying capacity of the habitat, regardless of whether FIV infection existed in the group. Vertical transmission, which is common in HIV, appears to be infrequent with FIV in nature. Certain strains of virus appear to be more likely to cross the placenta. Similar to HIV, FIV can be passed to kittens through the placenta, during the birth process, or via the milk. In contrast to the relative ease with which kittens can be experimentally infected via their mothers, in nature, FIVpositive queens rarely infect their offspring. The practical aspect of transmission research arises when clients present kittens for routine testing or when one of the cats in a household is found to be infected with FIV. Although kittens that nurse chronically infected queens are unlikely to become infected, they readily absorb colostral antibodies against FIV. Testing such kittens will result in a false-positive result, because diagnostic tests detect antibodies, not antigen. Most such kittens are truly uninfected, and colostral antibody titers decline over a period of several months. Therefore, a diagnosis of FIV infection should not be made on the basis of an antibody test before the age of 6 months. Because transmission by casual contact, such as sharing litter boxes and food dishes is uncommon, it is relatively safe to keep an FIV-positive pet in a household with other cats if the cats do not fight. However, in one study of a household with a large number of cats, 9 of 26 cats were FIV+ at the beginning of the study, and an additional 6 cats became infected over the next 10 years without evidence of fighting. DIAGNOSIS OF FIV INFECTION The American Association of Feline Practitioners recommends testing all cats for FIV. However, test sales figures indicate that a majority of cats are never tested. The mainstay of clinical screening for FIV infection is detection of circulating antibodies against FIV. Because FIV produces a persistent infection from which few cats recover, detection of FIV-specific antibodies in blood has been considered to be a reliable indicator of infection. Patient-side immunochromatic lateral flow antibody tests are commonly used for screening cats, and Western blot (WB) or IFA antibody tests are recommended for confirmation of infection. Diagnostic testing for FIV is discussed in more detail in Session 198. CLINICAL DISEASE SYNDROMES The course of clinical disease following infection with FIV is dependent on a number of factors, including the age and health of the cat at the time of infection, the dose and route of virus inoculation, the strain of the virus, and the immunologic background of the cat. Experimental infections of cats with different backgrounds have helped to differentiate primary viral effects from those that develop only in the presence of disease cofactors. For instance, there are marked differences in the development of disease syndromes in laboratory-reared specific pathogen-free (SPF) cats compared with random-source cats previously exposed to common feline pathogens such as upper respiratory infections and parasites. In one report of cats followed for 4 years after experimental FIV infection, both SPF and random-source cats experienced immunodeficiency marked by progressive inversion of the CD4+:CD8+ cell ratio and decreased mitogen responses. The random-source cats went on to acquire an AIDS-like syndrome characterized by stomatitis, recurrent respiratory disease, diarrhea, and weight loss. In contrast, several SPF cats developed Bcell lymphoma or neurologic disease, which are believed to represent direct viral effects, but not AIDS. This suggests that various infectious cofactors have a profound influence on the clinical course of cats infected with FIV. During natural FIV infection, most cats experience a prolonged asymptomatic period of several years following seroconversion. The most common disease syndromes diagnosed in the FIV-positive patients are stomatitis, neoplasia (especially lymphoma and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma), ocular inflammation (uveitis and chorioretinitis), anemia and leukopenia, opportunistic infections, and renal insufficiency. Both central and peripheral neurologic disease complicates the course of HIV infection of humans, and the same is true of FIV. The dementia of human AIDS is often characterized by a slight decline in cognitive ability or behaviour, changes that may be too subtle to recognize in cats. In some cats, however, obvious central and peripheral neurologic disease occurs and may take the form of seizures, striking behaviour changes, anisocoria, or paresis. Sensitive electrodiagnostic tests such as nerve conduction velocity and brain stem auditory evoked potentials may detect abnormalities in clinically normal FIV-infected cats. Neurologic abnormalities tend to respond favorably to treatment with zidovudine (AZT); in many cases, there is marked improvement within the first days of therapy. Chronic ulceroproliferative stomatitis is the most common disease syndrome induced in cats with long- standing FIV infection. Interestingly, this syndrome occurs only in cats that are also exposed to other infectious agents in addition to FIV, and does not readily develop in SPF cats. Concurrent calicivirus infection is often identified in the oral cavity of cats with FIVassociated stomatitis and may be one of the infectious cofactors capable of inducing stomatitis in combination with FIV. Recently, Bartonella henselae has also been implicated in stomatitis. Histologically, the mucosa is invaded by plasma cells and lymphocytes, accompanied by variable degrees of neutrophilic and eosinophilic inflammation. The cause of the syndrome is uncertain, although the histologic findings suggest an immune response to chronic antigenic stimulation or immune dysregulation. In addition, the circulating lymphocytes of cats with stomatitis have higher than normal expression of inflammatory cytokines, further implicating immune activation in the pathogenesis of this condition. The most effective treatment is extraction of all teeth, paying careful attention to removal of all of the roots of the teeth. In almost all cases of stomatitis in FIVpositive cats, long-term resolution of inflammation is achieved, and cats return to eating a normal diet. PREVENTION OF FIV INFECTION Test and removal programs conducted over the past 3 decades were very effective for eliminating FeLV infection from breeding catteries and preventing the adoption of FeLV-infected strays. At the same time, surgical neutering for population control became widely accepted, which decreased the production of FeLVinfected kittens, the primary source of new infections. In the 1980s, several vaccines against FeLV were introduced, which further strengthened control of FeLV. Consequently, the prevalence of FeLV, as well as its associated conditions such as lymphosarcoma, has steadily decreased during the past 20 years. With the success of FeLV control as a model, can we expect similar methods to work for FIV? In many respects, the answer is yes. Routine patient-side antibody tests are convenient, affordable, and highly reliable, although no test is perfect. In general, FIV is even less infectious than FeLV. In contrast to FeLV, kittens rarely acquire FIV from their infected mothers. Because FIV is primarily spread among male cats that fight and bite, endemic infections in purebred catteries are uncommon. Cats that reside peacefully together within households may not spread FIV among themselves. Thus, test and removal programs would be expected to be very successful at creating FIV-free populations. However, FIV testing is still not as widespread as it could be. Test sales in the US indicate that less than 10% of cats are ever tested for FIV. FIV is easily avoided by preventing cats from encountering other cats of unknown status. An interesting philosophical chasm separates the US from the UK in this regard. In the US, veterinarians and animal welfare workers encourage cat owners to confine their cats to prevent hazards of outdoor life, such as trauma and infections. In the UK, such confinement if often viewed as unnatural and inhumane, possibly contributing to some behavioral and health problems. Developing effective vaccines against FIV has proven to be a much bigger challenge compared to FeLV. Many approaches have been taken toward the development of an effective vaccine against FIV, but the same hurdles facing HIV prevention also apply to the feline virus. Both viruses have error-prone reverse transcriptase enzymes, which enhance the mutation rate of replicating virus and increases the opportunity for escape from immune surveillance. The viruses may also take advantage of specific antibody formation, using antibodies to enhance pathogenicity or to enter cells via immune complexes. Strategies explored to date include passive transfer of antibodies and immune cells, inactivated whole viruses, fixed infected cells, viral subunits, naked DNA, mucosal vaccination, gene-deficient viral mutants, and various adjuvants. To date, no approach has been completely successful in preventing infection after challenge, and in some cases immunization paradoxically enhanced viral replication and disease expression. Many promising prototype vaccines were only protective against the homologous strain from which the vaccine was derived; vaccines were less effective when cats were challenged with more distantly related strains. This is problematic, because cats in both North America and Europe may be exposed to a variety of strains (primarily A, B, and C). Adding to the difficulty in developing vaccines with broad protection is the difficulty in determining whether cats are truly free of infection following challenge. Recently, latent infectious FIV was isolated from necropsy tissues of cats that had tested negative by PCR for circulating virus for more than a year past vaccination and challenge. In another study, some cats experimentally exposed to FIV were negative by antibody testing, virus culture, and PCR. Further studies revealed that these cats had potent antiviral activity mediated by CD8+ T cells. When blood samples from these cats were cultured after the CD8+ cells were removed, infectious FIV was recovered. Clinically, cats in both of these studies had been diagnosed as being free of FIV prior to more extensive testing. This brings into question the results of vaccine challenge studies that evaluate infection status by conventional means. In July of 2002, Fort Dodge Animal Health released Fel-O-Vax FIV®, the first vaccine licensed for the prevention of FIV. Fel-O-Vax FIV® is a dual-subtype vaccine containing inactivated subtype A (Petaluma) and subtype D (Shizuoka) FIV combined with an adjuvant. Both cell-free and cell-associated virus are present in the vaccine. The combination of 2 genetically distinct subtypes is proposed to induce broadspectrum virus-neutralizing antibodies, although the full range of protection is still unknown. Fel-O-Vax is licensed for use in kittens 8 weeks and older. The primary inoculation series includes 3 doses administered 2 to 3 weeks apart. Annual boosters are recommended thereafter, although the maximum duration of immunity is unknown. The vaccine was challenged with a different type A strain of FIV (unspecified) 375 days after completion of the primary series. Challenge virus was administered by intramuscular injection to mimic a bite wound. Viral status was determined by culture and PCR every 2 weeks from 6 to 16 weeks post challenge. Cats with positive results for either test at 3 of the 6 time points were considered persistently infected. Results demonstrated that 17 of 19 unvaccinated controls (90%) became infected vs. 4 of 25 (16%) vaccinated cats, resulting in a preventable fraction of 82%. This represents substantial protection against the challenge strain of FIV, but it remains unknown how protective the vaccine will prove to be against other strains, particularly those that do not belong in the A and D strain families. Because Fel-O-Vax contains whole virus, cats respond to immunization by producing antibodies that are indistinguishable from those produced during natural infection. Thus, vaccinated cats will test "false-positive" in currently licensed antibody-based FIV diagnostic tests, including ELISA, immunochromatography, Western blot, and IFA. Kittens born to vaccinated cats will also test false-positive due to their absorption of colostral antibodies from the queen. Test interference is discussed in more detail in Session 198. A paradoxical transient increase in susceptibility to FIV infection has been documented in cats following immunization with either FVRCP or FIV vaccines. This may be due to the activation of lymphocytes stimulated by vaccination. Activated and replicating lymphocytes are the preferred target for FIV. Although this may not be clinically important for most cats, cats that reside with FIVinfected cats might benefit from separation from the infected cats for several weeks following routine vaccinations. TREATMENT OF FIV-INFECTED CATS Although cats may eventually succumb to diseases related to FIV infection, it is possible for many cats to enjoy an extended period of good health. Because many problems arise secondarily to the immunopathologic effects of infection, it is frequently rewarding to treat these related conditions. Several studies have reported that infected cats are likely to respond as well as uninfected cats when treated for lymphosarcoma, cryptococcosis, stomatitis, and anemia, among other conditions. In HIV infection, it is well documented that clinical outcome is improved when viral plasma burden is reduced. Current highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) often reduces viral burden to undetectable levels, although true cures are not observed. The result is that HIV patients are surviving longer with improved quality of life. HAART involves cocktails of drugs taken throughout the day. Side effects are common. Antiviral therapy is also effective in FIV-infected cats, although the drugs available to cats are limited and few controlled studies have been performed to support their use. AZT is the most thoroughly studied anti-FIV drug in cats. AZT reduces plasma virus load and improves CD4+ cell count. Recently, the nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor stampidine (25100 mg/kg PO BID) was reported to reduce viral burden in chronically infected cats treated in a short-term study. Other antiretroviral drugs have proved to be too toxic or ineffective in cats. Immunomodulators are the most widely used medications in FIV. Immunomodulators are suggested to benefit retrovirus-infected cats by restoring compromised immune function, thereby allowing the patient to control viral burden and recover from associated clinical syndromes. Unfortunately, neither immunomodulators nor antiviral drugs have received thorough evaluation in large long-term controlled studies in naturally infected cats. REFERENCES 1. Levy JK, Richards J, et al. Feline Retrovirus Testing and Management. Compendium of Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian 2001; 23: 652-657,692.