Peshkopia, Ridvan, D. Stephen Voss and Kujtim Bytyqi. 2013.

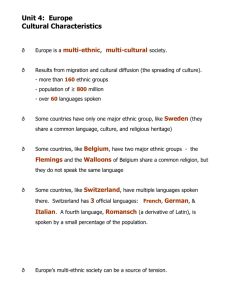

advertisement

Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 One Ethnic Group or Three: Ethnic Boundaries, Prejudices and Cultural Capital in the Independent Montenegro RIDVAN PESHKOPIA1 Universum College Kosovo D. STEPHEN VOSS University of Kentucky KUJTIM BYTYQI Universum College Kosovo UNIVERSUM COLLEGE WORKING PAPER SERIES 007/2013 PRISHTINA KOSOVO 2013 1 Contact: Ridvan Peshkopia, Universum College Kosovo. Address: Imzot Nik Prelaj St., Beni Dona Tower, Ulpiana Prishtinë, Kosovë. Tel.: +381 (0) 38 355 315; Mob.: +377 (0) 44763474; E-mail: ridvanpeshkopia@yahoo.com; ridvan.peshkopia@universum-ks.org 1 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 One Ethnic Group or Three: Ethnic Boundaries, Cultural Capital and Prejudice and in the Independent Montenegro Introduction The eruption of ethnic conflicts in the postsocialist Eastern Europe and its sub-region, the Balkans, has been able to inform us two major features. First, the imposition of the theoretically supranational communist regimes from 1917 and throughout the second half of the 1940 only froze an immature process of ethnic consolidation in several countries, and that process continued slowly beneath the communist iron jacket. Second, the simultaneous exposure of current ethnic groups to traditional values, domestic political dynamics and international developments―such as the growing impact of international organizations and globalization―makes the process of ethnic formation and consolidation more complex. Ethnic groups live today in a much interactive social environment and in some cases, it is almost impossible to find people who have not met certain out-group members of the same society. Such an interaction is expected to impact people’s perceptions for out-group members, and shape their attitudes accordingly. The complexity of contemporary interethnic relations increases as the growing frequency and intensity of intergroup contacts affect individuals, domestic structures and countries. Individual contacts affect group perceptions and, in turn, the latter influence the former. Jesse and Williams (2011) suggest a multi-level analysis in order to understand ethnic conflict. Since much of the process of nation-creation and consolidation might cradle the future ethnic conflict (Van Evera 1995), we employ such a multi-level analysis to analyze the state of 2 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 ethnicity among the Slavic and Albanian speaking populations in the newly independent Montenegro. The country emerged as independent in 2006, after 87 year of existence within Yugoslavia and more or less peaceful relations with former Yugoslavia powerhouse, Serbia. We consider several multi-level personal and aggregate variables, including social status as related to education, employment, economic performance and cultural capital, as well as some structural variables such as ethnicity, religious pertinence, people's perceptions for the out-group members, and the role of the EU membership perspective for Montenegro on how people from different ethnic groups feel toward out-group members. Our empirical analysis on Montenegro considers the temperature feelings for out-group members of citizens of Montenegro who identify themselves as ethnic Albanians, Bosniaks, Montenegrins and ethnic Serbs. Historically, the division line between those who self-identify as ethnic Montenegrins with those who claim to be Bosniaks and ethnic Serbs has been blurry, and only by the second half of the 1990s, the ethnic identity debate surfaced in Montenegro, arguably, mostly as a reflection of country’s political orientation (Bieber, 20003; Casperen, 2003).1 Therefore, now, the detachment after a lifelong contact is happening. Moreover, this detachment is not happening because of ethnic prejudices but because elite power calculations (Bieber, 2003; Casperen 2003; Huszka 2003). Therefore, by having been considered the same nation in Yugoslavia, the contacts between ethnic Montenegrins and Serbs in Montenegro were not a matter of choice but the state of society. Now that separation, as recorded by different accounts, has brought political frictions between both groups, prejudices between them are expected to further divide those groups.2 However, since there is no ethnic Montenegrin who have not met a Bosniak and Serb, the psychological nature of Bosniak, Montenegrin and Serb 3 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 ethnicity as related to each other and Albanians and the Roma can be analyzed only comparatively. We conduct our empirical analysis both in the light of Van Evera's (1995) conditions for ethnic conflict and the role that lifelong peaceful contacts have played in peaceful existence among different ethnic groups in Montenegro. If we take into account the number of factors that define ethnicity (language, religion, historical memories and myths) we expect citizens of Montenegro from different ethnic groups to feel sympathetic toward those out-group members with whom they share most of such characteristics. We find that the more variables are added in the regression analysis, the more the difference between Montenegrins and Serbs on the one hand and, separately, Bosniaks/Muslims and Albanians on the other become visible. We test our arguments with public opinion survey data that we collected in June and December 2010 in Montenegro. Ethnicity, Nation, the Individual and Society in the Contemporary Literature Since the effect that we are trying to explain, namely, perceptions of the out-group members as a measurement of ethnic affinities has been largely employed in social psychology, and because much of our concern rests with ethnic feelings/conflict, knowledge advanced thus far both in the literature of ethnic conflict and the social psychology of intergroup relations would help to establish the conceptual framework of our research, and set the stage for our hypothesis. Ethnicity, ethnic conflict and cohabitation For Gilley's (2004: 1158) concept of ethnicity as a part of personal identity that is defined by one or more markers like race, religion, shared history, region, social symbols or language. Powell 4 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 (1982: 43) adds tribes, nationality, and caste, elements that universalize the meaning of ethnicity. In some more specific terms for the European continent in general and particularly the Balkans, Byman (2002: 5) defines an ethnic group as gathering "people bound together by a belief on common kinship and group distinctiveness, often reinforced by religion, language, and history." Such bounds generate a sense of collective identity and perception of in-group members, those people who share such an identity, and out-group members, people who do not belong to the same collective identity (Esman 2004: 27-28; Jovitt 2002: 28; Weber 1968). From there, individualities are lost and they are replaced by collectivities who treat the groups either as uniformly friendly or uniformly hostile (Chirot 2002: 12). When individualities are lost, violence is more likely to emerge (Jowitt 2002: 29). Yet, ethnicity does not become nationalism unless members of the ethnic group appropriate a political program and carry territorial claims where to implement that program (Hearn 2006; Smith 2001; Barrington 1997). Since most of the world territory is already claimed under someone else's sovereignty, it is easily conceivable that the establishment of a new sovereignty would clash with the existing political order. From this perspective, nationalisms would sooner or later lead to ethnic conflict unless some accommodations are made to both the nationalist demands and/or to the group (Van Evera 1995). However, as Jowitt (2002: 27) notes, since ethnicity allows free exit and entry, it is simply a mode of identification, not a categorical identity. Therefore, not every ethnic conflict is set for all times, and the literature point to the perceptual factors of ethnic conflict. Van Evera (1995) provides a list of perceptive factors that might cause ethnic conflict, including the divergence among different ethnic groups of the way they perceive their history and current conduct; and the state of the economic conditions which, when deteriorate make public more 5 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 receptive to scapegoats. Religion, another ethnic characteristic that fall between culture and psychology, has become more often than not a complementary element to ethnicity (Jesse and Williams 2011: 93-140), and is some cases has also determined the ethnic boundaries (Suberu 1995). Intergroup contact theory and ethnic conflict: a literature review For more almost seven decades now, contributors to intergroup contact theory have developed an enormous conceptual and empirical research to test the hypothesis that contacts between competing and/or hostile groups reduce prejudices and debunk stereotypes (Allport 1954; Hewstone and Brown 1986; Pettigrew 1998; Brewer 2001; Brown and Hewstone 2005; Pettigrew and Tropp 2006). The fundamental promise of intergroup contact theory is that more contacts between individuals belonging to antagonistic social groups (defined by culture, language, beliefs, skin color, nationality, etc.) tend to undermine the negative stereotypes and reduce their mutual antipathies, thus improving intergroup relations by making people more willing to deal with each other as equals. Living in isolation, groups tend to develop intergroup bias, a systematic tendency to evaluate one’s own membership group (the in-group) or its members more favorably than a non-membership group (the out-group) or its members (Hewstone, Rubin, and Willis 2002). In a nutshell, more contact means less ethnic or cultural conflict, other things being equal (Miller 2002; Brewer and Gaertner 2001; Pettigrew and Tropp 2000; Pettigrew 1998a,b, 1971; Hamburger 1994; Amir 1976; Zajonc 1968; Works 1961; Allport 1954). Contact theory has attracted enormous empirical work in social settings characterized by deeply divided societies in the US and other developed countries (Nesdale 2006; Levin, Laar, 6 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 and Sidanius 2003; Cook 1984; Tajfel ed. 1982; Hamilton and Bishop 1976; Allport 1954) drew mainly from research conducted in the United States.3 Recently, intergroup contact theory has been employed to explore effects of intergroup contacts in regions with violent ethnic conflicts. The work performed on the Northern Ireland conflict (Hewstone et al. 2006; Hewstone et al. 2004; Tam et al. 2008; Tausch et al. 2007) has brought strong support for the hypotheses of the contact theory, and so has Sentama’s (2009) work on the post-conflict Rwanda. However, to our knowledge, the theory has not been tested in the Balkans, and the special place that the region occupies in the studies of ethnic conflict begs for empirical work in that direction. Critics of contact theory come from political science. Ideologies and the social norms that they produce assign stereotyped identities to members of other groups, and the nature of these social norms rather than interpersonal contacts make the difference between peaceful and conflictual relations (Jowit 2002; O’Leary 2002; McGarry and O’Leary 1995). This approach builds on a rational assumption and is supported by the widely known fact that most of the twentieth century’s ethnic killings have been performed by states under strong rational motivations rather than irrational crowd hysteria (Chirot 2002: 6). The elite-led breakups of former Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia serve as strong supports of this argument (Roskin 2002; Zimmerman 1996). Our common knowledge tells that contending groups tend to live adjacent to each other and that contact between neighbors tend to breed conflict. Forbes (2004) explains this paradox with the lopsided individual-level view of social psychologists, and suggests a model that would take into account fears of and resistance to assimilations that groups exhibit against perceived or real threats from other groups.4 Moreover, critics of the contact theory point to—and its contributors are aware of—the endogenous relationship between contact and prejudice; people 7 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 tend to contact out-groups toward whom they nurture positive feelings and shun contacts with out-groups toward whom they carry negative perceptions and stereotypes (Pettigrew and Tropp 2006; Forbes 2004; Voss, 1998; Wilson 1996; Herek and Capitanio 1996). Empirical work tries to resolve this issue either by using cross-sectional data and analyzing which path is stronger—in the studies of Van Dick et al. (2004), Pettigrew (1997), Powers and Ellison (1995), Butler and Wilson (1978) the path from contact to reduced prejudices is stronger. Alternatively, scholars might conduct longitudinal studies as the best way to resolve that problem (Pettigrew 1998)—in the case of Eller and Abrams (2003, 2004), Levin, van Laar, and Sidanius (2003), and Sherif (1966) longitudinal analysis show that optimal contact reduces prejudices over time (Pettigrew and Tropp 2006). Our capability is to establish any causal relations is reduced even more in cases when members from different ethnic groups live so intermingled that it is impossible to find people who have not met out-group members. Our following efforts focus on somehow bridging such gap by using comparatively analyzing the results of the regression analysis. One Ethnic Group or Three: Assessing Ethnic Boundaries in Montenegro Our efforts to explain ethnic boundaries in Montenegro confront us with some methodological challenges, especially related to one of our key variable, intergroup contact. It is easily perceptible that the specific historical context suggests a minimal variance of contacts between ethnic Montenegrins and Serbs as a key independent variable, but we expect to find more variance in the case of contacts of ethnic Montenegrins and Serbs with Albanians, Bosniaks and the Roma. Therefore, the only way to draw inferences is to consider also the effects of intergroup contacts with those groups. If the contact hypothesis holds, we should expect that, due to the lifetime close contacts between the ethnic Montenegrins and Serbs, the political frictions of the 8 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 late 1990s and the 2000s should have left no deep scars in their mutual feelings, and each of them is expected to like the other better than they like the other ethnic groups. Finally, both Montenegrins and Serbs will tend to like better those out-group members whom they have met somehow. We also control for the role of other social factors on group members’ attitudes toward out-group members. We expect age to play a role since people of different ages experienced different political systems and states of ethnic conflict. By the same token, years of education also reflect people exposure to interethnic dynamics in the country as well as the role of education in such relations. Economic factors have long been argued as determinants of ethnic conflict and almost everyone who has written on the subject credits the stagnant economy of the 1980s for the eruption of the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s (Jesse and Williams 2011; Chirot 2002; Zimmermann 1996; Djilas 1995; Diamond and Plattner 1994; Gagnon 1994). We expect variables that measure household financial performance during the last year as well as the employment status of respondents to play a role in their perception of out-group members. Meanwhile, some political scientists tend to place ethnic conflict on existential anxieties caused by fears of assimilation and perception of group extinction (Mulaj 2008; Forbes 2006; Oberschall 2002; Kaufman 2001). Fear can be gagged either as fear from the irredentist activity of an ethnic minority within the country or from a neighboring country dominated by the same ethnic group with some minorities in the given country. It is expected that such fear will drive hostile perceptions against the out-group members from that particular minority group. Religion is expected to play a role in people perception of out-group members, thus its implementation in any empirical analysis of the psychology of the ethnic conflict would help to gage more accurately the determinants of people’s feelings for out-group members (Jesse and 9 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 Williams 2011; Sells 2003; Glenny 1996; Kaplan 1996). Arguably, nationalistic mobilization needs religious legitimating (Velikonja 2003). Specifically, the introduction of religion in any explanatory model of the psychology of ethnic conflict/peace will help to understand that element of ethnic boundaries. Finally, the cultural capital; here we briefly elaborate migration as a form of cultural capital that, among other features, might have the potential to make people who experience it appropriate habits from the societies where they have worked and lived. We build on Bourdieu's ( Bourdieu and Passeron 1979) concept of cultural capital as a competence that becomes a capital when as it facilitates appropriating a society’s cultural heritage. Such a competence cannot be separated from the person who holds its, thus its formation combines personal talent and efforts with social norms one instilled by the social environment (see also Lareau and Weininger 2003). Therefore, foreign migration and exposure to foreign cultures might make migrants appropriate their habits. Such an appropriation of norms includes also the acceptance of others, especially in the case of the Balkan migration, which happens to be oriented toward the EU and the US, hence exposed not only to foreign cultures but also to the multiculturalism of their countries of destination. We expect higher feeling temperature toward out-group members from those who report to have had migrated before. Methodology and data We test models through regression analysis of both personal and aggregate data. We employ as a dependent variable the feeling temperature of Albanians, Bosniaks, Montenegrins and Serbs toward each other and toward the Roma in the range between 0 and 100. Since this variable could take any value between these margins, we employ linear regression analysis. 10 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 We employ a range of independent variables that operationalize the response of whether or not someone has met an out-group member (Albanian, Bosniak, Montenegrin, Roma and Serb), age, class, household economic performance during the last year, gender, religion, education, the fact that someone might have migrated abroad, whether or not they prioritize policies such as increasing employment and Montenegro’s membership in the European Union (EU), as well as their perception of out-group members as a threat to Montenegro’s sovereignty. Similar to other Balkan countries, the underdeveloped state of social research in Montenegro makes gathering data harder. Montenegro is a small country of only 650,000 inhabitants who gained independence only in 2006. Because its size, late independence, communist legacy, uncertain transition, the country lacks established survey institutes and private polling organizations of the size and variety found in Western Europe and North America; nor do external organizations of that sort regularly employ people with the linguistic and cultural background to operate in Montenegro. The Albanian minority in Montenegro lives too much of an extent geographically and culturally isolated to a degree than found in even the most segregated industrialized societies, but interactions among Bosniaks ethnic Montenegrins and Serbs is far more intense. In order to find the proper variance, we conducted surveys in three parts of the country: in the northeast we surveyed in the towns of Rozaj and Bijelopolje inhabited by a Bosniak majority; in the capital city, Podgorica, we sampled a metropolitan population with intensive contacts among the main ethnic groups, Montenegrins and Serbs; and in the southwestern city of Bar and Ulcinje, with the former being a mixture of all ethnic groups living in Montenegro and the latter the hub of the Albanian minority in Montenegro. Throughout this line running through the capital city of Podgorica we are confident that the geographic distribution of our survey sample covers the 11 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 potentially best sample frame. Indeed, as the sample itself shows, due to the high internal mobility and the small size of the country, we have been able to interview people from all Montenegrin regions who have happened to be on the survey sites. Conventional sampling methods are inappropriate for our specific research question. Our lack of appropriate tools to conduct telephone or email surveys, and the impossibility to implement door-to-door sampling methods―partly because residential patterns are complicated by the close proximity of single-family and multi-family dwellings, and partly because in most communities either the norms, the family structure, or suspicion of the state rules out approaching people in their homes―risked to turn conventional methods in producers of strong and systematic biases in the sample. For these reasons, we are representing here findings from the Three-Region Survey of Montenegro Citizens’ Perceptions of Out-groups within the SevenCountry Survey of Balkan Perceptions of Ethnic, Racial and Social Divisions using trained interviewers. The survey combines a stratified design for selecting communities with nonprobability methods for identifying individual respondents that were tailored to suit the living patterns found in each community. The stratification approach maximizes sample variation across the main explanatory variables: ethnicity of respondent, socioeconomic class, age, gender, religion affiliation, education, migration experiences, political preferences, and likelihood to have contacted someone from other ethnic groups living in the country. The non-probability sampling within each community, on the other hand, attempts to approach the ideal of randomization, thus seeking a representative population on possible intervening variables. The survey went into the field in the June of 2010 in Ulcinje, an Albanian populationdominated small touristic town near the Albanian border where the ethnic Albanian population lives almost isolated from the rest of the country. In December 2010, teams of our interviewers 12 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 conducted surveys in Rozaje and Bijelopolje near the Kosovo border, in the capital city of Podgorica located in the center-south, and in the coastal city of Bar. In December, we also returned to Ulcinje in order to increase the size of the sample from that area. Table 1 includes the survey sites in Montenegro. Country Table 1. Survey sites in Montenegro Alternate Name Name MONTENEGRO Podgorica, Capital city MONTENEGRO Town of Rozaj MONTENEGRO Town of Bijelopolje MONTENEGRO Town of Ulcinje MONTENEGRO City of Bar Majority Montenegrin Bosniak Bosniak Ulqin Albanian Montenegrin/Serb Although the specific approach of the Seven-Country Survey of Balkan Perceptions of Ethnic, Racial and Social Divisions to selecting respondents varied from community to community, according to the social patterns encountered in each place, certain traits of the interviewing remained constant. Every questionnaire was delivered in a face-to-face interview, with questions posed in the respondent’s primary language by an interviewer of the same ethnic background. In the case discussed by this paper, the questionnaires were conducted in Albanian. The research teams dispatched to each community consisted entirely of university students trained by the authors, either in a University of New York Tirana (UNYT) research methods course or in an abbreviated ‘survey methodology certificate’ program designed specifically for recruits to this survey. Both sets of students received an introduction to systematic interviewing and to the concept of scientific sampling. They practiced filling out questionnaire forms efficiently, to prevent respondents from dropping off during the interview. They were instructed on how to avoid the negative effects of selection bias: by dressing professionally to elicit good 13 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 responses, by approaching potential respondents in a fashion that would encourage their cooperation, and by practicing the phonetics needed to ask individual questions. Members of the research team spread out within each city and town to ensure maximum geographic dispersion. Typically interviewers traveled to a public place and, after taking up their posts, identified potential respondents using what in the American context is casually called “man on the street” interviewing―and among scholars referred to (even more derisively) as convenience sampling. The standard dismissal of this research design is so widespread, and the concern with potential selection bias when considering this method so severe, that it is worth explaining why we view the approach as the superior option given our research goals. Despite skepticism for such methods when applied in the Western context, the research environment in the Balkans strongly favors conducting surveys in public spaces, and not simply due to the inefficacy of rival approaches. Rather, much of Balkan social life takes place in “the bazaar”—from village squares to town fountains to city parks or gardens, from highly trafficked downtown sidewalks to smaller shops or cafes—so a potential respondent will view a stranger’s approach in public places as acceptable if not natural. In many of the communities selected for our survey, the common practice is for families to promenade at dusk, unwinding after a busy day in anticipation of their nightly meal. Much of the population will be out and about during prime time. Far from resisting taking a survey during such times of relaxation, potential respondents typically enjoyed the diversion represented by a discussion of public affairs with young students from the nearby university. A public approach also obviates the anxiety that respondents might feel when approached by an educated stranger at their homes. Ironically, approaching respondents in their homes posed quite a different research burden when the interview subjects trusted the members of our student team. Some other times, interviewers 14 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 could not conduct interviews efficiently because the expectations of Balkan hospitality required that respondents invite the student inside, offer them refreshment, and otherwise extend the conversation beyond sustainable limits. Simply put, awareness of the rhythms of Balkan life cautions a researcher against trying to transplant Western survey mechanisms to the region. While participation in this public sphere is so widespread that “man on the street” interviewing does not bring the sort of selection bias that it would in other industrialized countries, indeed arguably represents an “appropriate technology” given Balkan community life, that does not mean we can dismiss other forms of bias that typically will emerge from a sample of convenience. Specifically, we had to train interviewers against selecting for the most cooperative potential respondents and toward selecting a more representative sample. Interviewers dispatched to public areas would establish a rubric, typically to approach the third person encountered after each attempt to conduct an interview. Yet in some small and sparsely populated villages, they had to interview every person they encountered. Interviewing took place not only around twilight (roughly 6 pm – 9 pm in the summer and 2 pm – 6 pm in winter), when most citizens are engaging in public life out of doors, but also in the morning (roughly 9 am – 12 pm) because those hours allow access to the one population that would be most poorly represented in the evening: Women with large families whose household duties might bind them to the home.5 The overall design of the Three-Region Survey of Montenegro Citizens’ Perceptions of Out-groups within the Seven-Country Survey of Balkan Perceptions on Ethnic, Racial and Social Divisions is thus a non-probability sample that permits no straightforward analytical derivation of sampling error. At root, confidence in the results cannot be reduced to a simple number, and must derive from the combination of scientific principles and sensitivity to research context that 15 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 informed the overall design. However, such a method is is as close to a stratified representative sample as we can imagine one collecting from these countries, certainly without the sort of exorbitant expenditure that few research questions could justify. Moreover, such an approach allows us to expand the study of important substantive topics to places often missed because of their imperviousness to more comfortable and familiar research methods. Specifically, it gives us the valuable theoretical leverage provided by the Balkans for understanding the political psychology of ethnic and social divisions in the Balkans and finding out how they would interplay in order to overcome such rifts (see also Peshkopia 2010; Peshkopia and Voss 2010). Analysis Table 2 compiles descriptive statistics of the dependent variable, namely the feeling temperature of Montenegro's four main ethnic groups for each other and two other minor ethnic groups who live in Montenegro: Croats and the Roma. We probed people's feeling temperature toward the Macedonians and Greeks in order to inquire whether some cultural similarities and differences outside the Montenegrin context, but within the Balkan political context, might count for people's feeling temperatures toward them. We also gagged temperature feelings for the Americans, as we expect deep sentiments toward them in the region.6 We also asked people about their feeling temperature toward homosexuals. However, some of these variables are not parts of our models. Our four ethnic groups can be grouped according to two patterns: First, the ethnolinguistic pattern where on the one side rest three groups who speak almost the same Slavic language (Bosniaks, Montenegrins and Serbs); and on the other the Albanians who speak their own, non-Slavic language. Second, the religious pattern where on the one side rest the 16 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 Table 2. Feeling Temperatures for the Out-group Members Among the Ethnic Albanians, Bosniaks, Montenegrins and Serbs Living in Montenegro Feeling Temperatures Albanians Bosniak/Muslims Montenegrins Feeling temperatures for Albanians Observations: 209 Mean: 91.38 S.D.: 19.42 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 177 Mean: 59.29 S.D.: 33.85 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 177 Mean: 53.32 S.D.: 31.96 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 173 Mean: 35.88 S.D.: 30.95 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 177 Mean: 14.53 S.D.: 23.91 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 178 Mean: 28.89 S.D.: 28.61 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 183 Mean: 46.94 S.D.: 33.08 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 167 Mean: 25.49 S.D.: 30.69 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 183 Mean: 20.56 S.D.: 28.11 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 165 Mean: 14.80 S.D.: 29.20 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 48 Mean: 54.79 S.D.: 40.48 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 46 Mean: 52.39 S.D.: 46.82 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 47 Mean: 97.45 S.D.: 14.81 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 48 Mean: 62.50 S.D.: 40.92 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 46 Mean: 38.91 S.D.: 44.63 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 47 Mean: 67.23 S.D.: 39.33 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 46 Mean: 92.39 S.D.: 23.49 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 46 Mean: 41.96 S.D.: 40.31 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 48 Mean: 59.38 S.D.: 41.43 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 46 Mean: 1.52 S.D.: 7.88 Min.: 0 Max.: 50 Observations: 155 Mean: 59.74 S.D.: 38.11 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 151 Mean: 52.32 S.D.: 38.64 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 151 Mean: 76.69 S.D.: 32.67 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 151 Mean: 59.11 S.D.: 37.39 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 151 Mean: 49.64 S.D.: 36.20 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 152 Mean: 66.45 S.D.: 32.86 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 157 Mean: 93.25 S.D.: 20.42 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 152 Mean: 48.78 S.D.: 37.82 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 155 Mean: 81.94 S.D.: 29.57 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 149 Mean: 15.17 S.D.: 31.66 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Feeling temperatures for Americans Feeling of temperatures for Bosniak/Muslims Feeling temperatures for Croats Feeling temperatures for Greeks Feeling temperatures for Macedonians Feeling temperatures for Montenegrins Feeling temperatures for the Roma Feeling temperatures for Serbs Feeling temperatures for Homosexuals Serbs Observations: 53 Mean: 36.23 S.D.: 37.89 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 54 Mean: 38.52 S.D.: 39.78 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 54 Mean: 58.15 S.D.: 35.45 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 57 Mean: 55.96 S.D.: 38.31 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 58 Mean: 53.62 S.D.: 41.07 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 55 Mean: 68.91 S.D.: 33.09 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 58 Mean: 90.52 S.D.: 23.80 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 55 Mean: 33.27 S.D.: 37.81 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 59 Mean: 95.68 S.D.: 14.03 Min.: 50 Max.: 100 Observations: 48 Mean: 12.92 S.D.: 31.75 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 predominantly Muslim Albanians and the Bosniaks; and on the other the Christian Orthodox Montenegrins and Serbs. A glance at the data shows that feeling temperatures across these 17 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 groups does not follow any of those patterns and variations emerge both within each pattern and across patterns. For instance, one might think that Albanians would like their fellow Muslim Bosniaks better due to religious affinity (53.32), but surprisingly we discover that Serbs beat them in those feelings (58.15). In turn, Montenegrins seem to like Albanians more than Bosniaks do (59.74 versus 54.79), a fact that undercuts both the ethnolinguistic and the religious patterns. However, Albanians seem to nurture lower regard for the Macedonians (28.89), another southern Slavic population than what members of the other three groups feel for Macedonians: Bosniaks (67.23), Montenegrins (66.45), and Serbs (68.91). By the same token, Albanians feel less warm toward Croats (35.88) than members of the other three groups feel toward the latter: Bosniaks (62.50), Montenegrins (37.39), and Serbs (38.31). This is a clear signal that there is a tendency to set apart Albanians from the other Slavic speaking groups, but the latter are far from having a harmonious relationship among them. At the only instance where both ethnolinguistic and religious pertinence overlap, the case of Montenegrins and Serbs, feeling temperatures show mutual high regards (81.94 and 90.52). Moreover, interesting interpretations could come with feeling temperatures toward Greeks of the Albanians (14.53), Bosniaks (38.91), Montenegrins (49.64), and Serbs (53.62). Usually Greece has no role in Montenegrin politics and society, and yet people, especially Albanians, seem to nurture deep negative feelings toward them. The fact that Serbs rest on the other opposition, might instruct us that, rather than personal perceptions, Albanians' and Serbs' feelings toward the Greeks are affected by politics of their mother countries, namely Albania and Serbia, as well as the regional extension of Albanian-Serb rivalries and the Greek alignment with the latter over the international status of Kosovo.7 18 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 Serbs of Montenegro tend to be more friendly toward the Albanians of Montenegro even when the latter do not respond similarly to those feelings (36.23 versus 20.56); while they share feelings at comparable levels with the Bosniaks (58.15 versus 59.38). But Serbs of Montenegro do not look extremely hostile against Croats as well (55.96), even though the memories of the Croat and Bosnian wars have affected the Serbs of Montenegro as well. On the other hand, they don't seem extremely friendly with Greeks (53.62), even though the latter have been their unwavering allies throughout all the post-Yugoslav turmoil. Going to the core of our argument, our data suggest that the political divisions of the late 1990s and the 2000s have not managed to dramatically separate Montenegrins and Serbs. However, due to the fact that almost every Montenegrin in our sample responded to have met a Serb and vice versa, it is impossible to detect the effect of contacts on feeling temperatures between these groups. Table 3 comprises three predictive models of temperature feelings of ethnic Albanians, Bosniaks/Muslims and ethnic Serbs toward ethnic Montenegrins. The dependent variable, respondents’ feeling temperature toward ethnic Montenegrins, and two independent variables, people policy preferences toward the EU and employment are opinion variables while the rest of the variables can be considered to be aggregate variables even though we gathered them by asking people of their values. Ethnic Montenegrins are dropped from the sample. The limited space allows for the detailed interpretation of only the most relevant variables. Results from Model 1A support our findings in other research conducted on such topic; feeling temperature for out-group members from rival ethnic groups tends to increase with age (represented by a coefficient value of -0.21), and a decrease in household incomes tends to curb feeling temperature toward out-group members (a coefficient value of 12.95). Both these values carry statistical confidence. The coefficient of our key variable (whether or not someone has met 19 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 TABLE 3 - Explaining the feeling temperature of ethnic Albanians, Bosniaks/Muslims and ethnic Serbs toward ethnic Montenegrins Linear Regression MODEL 1A Predictive Model MODEL 1B Predictive Model Serb 10.43 (10.597) 7.1 (11.087) -33.242 Bosniak/Muslim Albanian Year born Years of education Gender/Male Trend in household incomes EU as policy priority Employment as a policy priority -0.21 (0.240) 0.18 (1.688) -0.29 (8.331) 12.95 (5.616) 3.48 (2.637) 5.42 (3.240) (10.012) -0.21 (0.157) 0.623 (0.792) -7.69 (4.130) 1.94 (2.882) 3.14 (1.491) 6.19 (1.779) * ** MODEL 1C Predictive Model *** * *** -0.28 (14.208) -17.38 (29.680) -37.78 (14.208) -0.09 (0.171) 0.38 (-0.842) -8.78 (-4.290) 1.97 (-2.954) 2.74 (1.550) ** * *** Employed in private sector 1.24 (8.944) 10.14 (9.542) -1.99 (9.546) -1.73 Employed in public sector Self-employed Unemployed (9.494) Met a Montenegrin 1.12 23.73 (18.380) (13.630) * 5.09 (16.795) Bosniak/Muslim met a Monetnegrin 43.2 (27.608) Albanian met a Monenegrin 19.99 (21.769) Muslim religion 32.03 (22.384) Catholic religion 45.39 * (24.130) Eastern Orthodox religion 58.87 (25.414) Ever migrated Constant Observations Adjusted-R2 -16.31 * 2.81 3.95 (8.745) (4.890) (4.804) 437.3 434.71 189.88 (471.056) (309.335) (335.827) 50 0.135 239 0.333 236 0.314 NOTE: All models use the post-stratification weights provided with the survey data. Standard errors reported in parentheses: *** p < .01 ** p < .05 * p < .1 20 ** Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 an ethnic Montenegrin) goes in the predicted direction but it lacks statistical significance. Coefficients of other variables go in the predicted directions: education and aspiration to join the EU make someone to feel warmer toward out-group members, while being male conditions lower temperature feelings toward out-group members. It should be noted that the coefficients of these variables lack statistical significance and we remain cautious to draw conclusions from them at this stage. What puzzles us, however, is the direction of the coefficient of the prioritization of employment policy variable; we expected that people who prioritize employment are usually unemployed and the latter usually generates bitter feelings against outgroup members, especially when they are from country’s dominant ethnicity. However, the lack of statistical significance of that variable shows that such findings might well be an accident, and that responses on that question are so spread so it is not possible to confidently notice any impact of this variable on the dependent variable. What surprises us at this point is the high impact that migration has on lower feeling temperatures toward ethnic Montenegrins (-16.31 with a p < 0.1 statistical significance). The introduction of ethnicity in Model 1B seems to bring more clarity. Being an ethnic Albanian in Montenegro strongly signifies lower feeling temperature for ethnic Montenegrins (33.242) while being an ethnic Serb might predicts warmer feelings toward Montenegrins (10.42). Now that much of the effect on people’s feeling temperature on ethnic Montenegrins have been taken over by ethnicity, results that conform existing arguments as well as out theoretical claims surface: first, past meetings with an ethnic Montenegrin predict warmer feeling temperature toward them (coefficient value of 23.73 and p < 0.1) and EU membership as a common project causes people to feel warmer toward out-group members (coefficient value of 3.14 and p < 0.01). 21 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 While Model 1C seems to be weaker than the previous two models, it remains very instructive for our purpose. We introduce here two groups of variables: employment and religion. Variables in both these groups seem to have taken some of the weight of other variables. Thus, for instance, the Eastern Orthodox variable receives a coefficient of 58.87 (indeed, the higher coefficient of any variable of this group of models) with a p < 0.05. Knowing that only ethnic Montenegrins and Serbs practice Eastern Orthodoxy in Montenegro, we can infer strong feelings of oneness from ethnic Serbs toward ethnic Montenegrins. As a result, the coefficient value -0.28 of the variable Serb with a p > 0.1 can be considered as random noise. Model 1C brings about some more developments. First, it asserts that Balkan ethnic prejudices might be men’s business as the coefficient value of the Gender drops to -8.78 for a p < 0.05. Second, EU membership aspirations continues to predict warmer feelings toward the outgroup members as the respective variable takes a coefficient value of 2.74 for a p < 0.1. Models 2A, 2B, and 2C (Table 4) explain the weight of the selected variables on people’s feeling temperature toward ethnic Serbs in Montenegro, with Serbs dropped from the sample. From the ethnicity variable, being an ethnic Albanian shows a strong negative impact on feeling temperature (-39.25 and p < 0.001), while being an ethnic Montenegrin tends to affect feeling temperature positively (16.1) and being a Bosniak/Muslim tends to affect it negatively (-20.44), but none of them carries any statistical significance. Model 2B introduces two sets of new variables: employment category and religion affiliation. Variables such as Serb, Bosniak/Muslim and Albanian experience slim coefficient values but both their directions and statistical significance remain the same. Now the variable Trends in Household Incomes (coefficient value of -5.1 and p < 0.1) shows a growing nervousness of other ethnic groups against Serbs in the conditions of economic decline. 22 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 TABLE 4 - Explaining the feeling temperature of ethnic Albanians, Bosniaks/Muslims and ethnic Montenegrins toward ethnic Serbs Linear Regression Montenegrin Bosniak/Muslim Albanian Year born Years of education Gender/Male Trend in household incomes Perception of Serbia as a threat Perception of Serb minority as threat EU as policy priority Employment as a policy priority MODEL 2A Predictive Model 16.1 (11.676) -20.44 (12.573) -39.25 (11.510) 0.08 (0.154) 0.17 (0.797) -3.72 (4.112) -5.54 (2.759) -7.79 (5.220) -13.23 (5.882) 3.14 (1.491) 6.19 (1.779) MODEL 2B Predictive Model MODEL 2C Predictive Model 16.08 (10.820) -13.62 (11.475) -35.9 15.81 (10.836) -55.64 (35.282) -39.79 *** (10.385) 0.08 (0.170) -0.76 (0.797) -5.17 (0.797) -5.1 (2.776) -7.48 (5.039) -0.48 (0.521) -1.99 (1.477) *** *** * 0.42 (9.275) -1.06 (9.655) -11.48 (9.551) -3.94 Employed in public sector Self-employed Unemployed *** (9.656) 21.78 (7.730) Met a Serb An Albanian met a Serb Muslim religion Catholic religion 32.03 14.6 (21.017) * (24.130) Adjusted-R2 58.87 2.81 -0.08 (9.288) -1.43 (9.670) -11.81 (9.560) -3.48 (22.384) 45.39 Eastern Orthodox religion Observations * (9.667) 16.25 (7.730) 43.05 (34.059) 3.53 (19.104) A Bosniak/Muslim met a Serb Constant ** *** Employed in private sector Ever migrated (21.365) 0.09 (0.171) -0.68 (0.800) -4.75 (4.120) -5.56 (2.814) -7.64 (5.046) -0.46 (0.521) -2.13 (1.481) 37.11 (22.834) ** 29.21 (21.649) (21.666) 8.02 8.73 (4.890) (4.675) (4.713) 434.71 -108.59 -113.61 (309.335) (333.397) (333.943) 256 249 249 0.487 0.524 0.524 23 * Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 NOTE: All models use the post-stratification weights provided with the survey data. Standard errors reported in parentheses: *** p < .01 ** p < .05 * p < .1 Moreover, the variable Unemployed shows a negative impact of unemployment on feeling temperature against Serbs for a p < 0.01, thus showing that people are inclined to blame Serbs, the most powerful minority, for their economic woes. Being a Catholic (they are only among the Albanians) represents greater sympathy for Serbs while, as predicted, affiliation with Eastern Orthodoxy strongly impact positive feelings toward Serbs. Table 5 displays four explanatory models of temperature feelings of ethnic Albanians, Montenegrins and Serbs toward Bosniaks/Muslims. Striking in these models is the persisting strong negative perception of the Albanian Muslims toward Bosniaks/Muslims, which at the model 3D produces a coefficient value -79.35 (p < 0.01), especially emphasized by pullout of the Montenegrin variable. Overall, models 3C and 3D show the dominance of psychological factors in feeling temperatures toward out-group members. Those who perceive Bosniaks/Muslims as threat to Montenegro sovereignty tend to bear negative feelings for them (-30.01 and p < 0.1). Contact hypothesis receives substantial support: being an Albanian who has met a Bosniak/Muslim affects the dependent variable with a coefficient value 60.07 (p < 0.01); being a Montenegrin produces a coefficient 26.47 (p < 0.05); while the effect of the Serb*Bosniak/Muslim produces a statistically insignificant coefficient value. Not surprisingly, those who report to be Eastern Orthodox do not seem to consistently report positive feelings toward Bosniaks/Muslims while the effects of being Catholics and Muslims (most of them Albanians) seem to produce only weakly statistically significant coefficient values (44.03 and 39.27 respectively with p < 0.1 for both them). The latter values seem to reflect some solidarity 24 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 between a religious minority (Albanian Catholics) toward an ethnic minority (Bosniaks/Muslims). By and large, models 3C and 3C display the primacy of psychological TABLE 5 - Explaining the feeling temperature of ethnic Albanians, Montenegrins and Serbs toward Bosniaks/Muslims MODEL 3A Linear Regression MODEL 3C MODEL 3D Predictive Model Predictive Model Serbian -6.59 (11.695) -6.01 (12.570) -8.09 (27.128) -34.56 (24.317) Montenegrin 14.92 (11.078) -9.57 18.75 (11.502) -9.42 26.47 (11.983) -52.88 (11.002) 0.03 (0.147) 0.32 (0.790) -2.81 (3.980) 0.47 (2.752) (11.328) 0.16 (0.161) 0.73 (0.845) -2.62 (4.463) -1.81 (2.929) (25.736) -0.03 (0.182) 0.68 (0.869) -3.64 (4.475) -3.21 (2.922) -0.05 (1.458) -38.49 (15.625) -1.97 (1.552) Albanian Year born Years of education Gender/Male Trend in household incomes Predictive Model MODEL 3B Predictive Model Perception Bosniak minority as threat EU as policy priority Employment as a policy priority 2.37 -0.51 (1.703) (1.885) Employed in private sector Employed in public sector Self-employed Unemployed Met Bosniak/Musliman 7.89 (6.335) 1.99 (7.089) Serb met Bosniak/Muslim Albanian met Bosniak/Muslim ** -30.1 (17.604) -0.89 (1.533) ** -79.35 * 5.25 (10.192) -4.17 (10.424) 2.49 (10.456) 7.55 (10.836) -21.94 (21.541) 15.79 (25.589) 33.6 (10.836) -48.41 (24.511) 42.26 (28.052) 60.07 (23.435) (26.199) 26.47 (11.983) * (21.929) Catholic religion 44.03 (23.877) Eastern Orthodox religion Ever migrated -30.1 (17.604) -0.89 (1.533) 5.25 (10.192) -4.17 (10.424) 2.49 (10.456) 7.55 39.27 39.27 * ** ** ** * (21.929) * 44.03 (23.877) 11.95 11.95 (22.610) (22.610) -3.41 -0.98 1.69 1.69 (5.217) (5.609) (5.510) (5.510) 25 *** (23.726) -0.03 (0.182) 0.68 (0.869) -3.64 (4.475) -3.21 (2.922) Montenegrin met Bosniak/Muslim Muslim religion (dropped) * Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 Constant Observations Adjusted-R2 -19.1 -242.33 118.61 145.08 (288.725) (316.390) (355.571) (356.210) 321 247 241 241 0.105 0.153 0.21 0.21 NOTE: All models use the post-stratification weights provided with the survey data. Standard errors reported in parentheses: *** p < .01 ** p < .05 * p < .1 factors over other socio-economic factors in ethnic conflict/peace. Also, differently from models 1A and 2C, the cultural capital that migration experience arguably produces seems to be not enough consistent as to offer a statistically significant coefficient value. This outcome makes us think about various migration experiences of different ethnic groups as well as different capabilities to convert them into cultural capital, a question that would beg further investigation in the future. Table 6 offers two explanatory models on the feelings of Bosniaks/Muslims, ethnic Montenegrins and Serbs toward ethnic Albanians living in Montenegro. Those models offer a more balanced impact of economic and psychological factors as it is demonstrated by the negative impact that the deterioration of household incomes on people’s feelings toward ethnic Albanians (coefficient value -10.26 and p < 0.05 in Model 4A and coefficient value -12.98 and p < 0.01 in Model 4B); and the perception of Albania as a threat to Montenegro’s sovereignty (coefficient value -43.1 and p < 0.01). The lack of statistical significance for the coefficient values of the variables that would help testing contact theory warns us of deeply asymmetrical patterns of prejudice reduction resulting from intergroup contacts. By the same token, those models also show a lack of consistency in evidence that migration experiences can produce cultural capital of the kind that frees its carriers from ethnic prejudices. Table 7 displays two explanatory models of the temperature feelings of ethnic Albanians, Bosniak/Muslims, ethnic Montenegrins and ethnic Serbs toward the Roma people. Model 5A offers strong support for the contact hypothesis, and the fact it we loses statistical significance when we add a series of interaction variables should not discourage us since much of that effect 26 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 now rests hidden under the multicollinear relationship between the single variables and their composites. Other than that, both models are generally weak and lowly instructive except for fact TABLE 6 - Explaining the feeling temperature of ethnic Montenegrins, Serbs and Bosniaks/Muslims toward Albanians Linear Regression Serbian Montenegrin Bosniak/Muslim Year born Years of education Gender/Male Trend in household incomes Perception of Albania as a threat EU as policy priority Employment as a policy priority MODEL 4A Predictive Model MODEL 4B Predictive Model -18.61 -18.45 (13.363) (21.069) -1.83 (12.281) 4.47 (13.169) 0.05 (0.199) -0.35 (1.176) 5.29 (5.724) -10.26 (4.144) -41.76 (5.220) 2.27 (2.124) 5.05 (2.602) 4.09 (12.139) -24.18 (27.901) 0.01 (0.226) 0.27 (1.226) 4.82 (5.969) -12.98 (4.435) -43.1 (13.278) 3.1 (2.127) ** * Employed in private sector 0.91 (10.358) Employed in public sector -12.76 (11.145) -14.45 (11.316) -7.09 Self-employed Unemployed Met Albanian (11.009) -8.3 (13.889) 13.8 3.85 (8.607) Bosniak/Muslim met Albanian Serb met Albanian 10.71 (18.601) Muslim religion 34.71 (36.788) Catholic religion 38.95 (44.834) Eastern Orthodox religion 7.75 (36.910) Ever migrated Constant Observations Adjusted-R2 -8.19 -7.55 (7.541) (7.398) -53.51 43.98 (392.440) (447.089) 196 0.154 192 0.185 27 *** *** Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 NOTE: All models use the post-stratification weights provided with the survey data. Standard errors reported in parentheses: *** p < .01 ** p < .05 * p < .1 that the negative impact of being a Serb on feeling temperature toward the Roma (-24.18) carries statistical significance (p < 0.1), and that, again, decline in household incomes is reflected in hostile behavior against the out-group members, in this case the Roma (a coefficient value -4.82 and p < 0.1) even though the Roma have no any visible role in the economic life of the country and seem to threat nobody’s job. Moreover, there is inconsistency among all ethnic and religious communities regarding their feelings toward the Roma, thus reinforcing evidence of the widespread racial prejudices in the Balkans (Marushiakova and Popov 2000). Conclusions While our models answered some of our questions, they could not answer definitively most of them, and also opened further questions. Although none of the models could be used separately as an explanation of all feeling temperatures of different ethnic groups toward each other, combining them in a more detailed comparative analysis can offer instructive insights on the state of ethnicity and nationalism in Montenegro. First, it is clear that, ethnic frictions notwithstanding, Bosniaks/Muslims, ethnic Montenegrins and Serbs feel toward each other much closer than they feel toward Albanians. In turn, also Albanians feel toward Bosniaks/Muslims, ethnic Montenegrins and Serbs similarly. The fact that Bosniaks/Muslims share the same religion with most of the Albanians seem to not impact much the latter's perceptions of the former, and Catholics, most of them Albanians, do feel roughly the same as Muslims toward both Bosniaks/Muslims and ethnic Montenegrins and 28 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 Serbs. Obviously, indifferent of religious impact on ethnicity as they are, Albanians seem to perceive alike Montenegro's other Slavic speaking ethnic groups. TABLE 7 - Explaining the feeling temperature of ethnic Albanians, Bosniak/Muslims, Montenegrins, and Serbs toward Roma Linear Regression Montenegrin Bosniak/Muslim Albanian Serb Year born Years of education Gender/Male Trend in household incomes Perception of minorities as threat EU as policy priority Employment as a policy priority MODEL 5A Predictive Model MODEL 5B Predictive Model -8.98 (13.132) -8.66 (14.237) -28.21 (12.986) -24.18 (13.740) -0.22 (0.160) 0.69 (0.833) 1.69 (4.291) -4.82 (2.919) 15.9 (26.156) 15.67 (26.489) 0.61 (25.315) 12.92 (26.770) -0.25 (0.188) 0.84 (0.900) 1.52 (4.616) -5.07 (3.092) * * -3.67 (2.799) 1.44 (1.550) -2.4 (2.929) 1.33 (1.560) 3.01 (1.952) Employed in private sector 11.87 (9.817) 7.14 (10.390) 9.77 (10.116) 11.54 Employed in public sector Self-employed Unemployed Met Roma 12.66 (4.655) (10.361) 53.88 (28.322) *** Bosniak/Muslim met Roma -32.14 (31.536) -40.89 (29.224) -54.84 (31.225) -34.17 (29.902) Albanian met Roma Serb met Roma Montenegrin met Roma Muslim religion 23.79 (25.007) Catholic religion 35.71 29 * Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 (26.860) Eastern Orthodox religion 24.99 (25.821) Ever migrated Constant Observations Adjusted-R2 -5.88 -1.34 (5.329) (5.308) 457.78 477.62 (313.703) (371.376) 302 0.121 294 0.108 NOTE: All models use the post-stratification weights provided with the survey data. Standard errors reported in parentheses: *** p < .01 ** p < .05 * p < .1 While, in general, the data analysis suggests support for the contact hypothesis, inconsistencies acrossethnic groups plague solid conclusions. Elsewhere it has been argued that some other Balkan experiences showed prejudice reduction beyond Allport conditions (Peshkopia, Voss and Bytyqi 2010). This research shows that contact effects in reducing prejudices tend to differ across ethnic groups even when they live in the same institutional setting. The inconclusive findings on the role of economics, employment in ethnic hostilities suggest further research. However, data analysis suggests that such factors remain secondary to psychological factors as their impact dwindles or disappear altogether when the latter are introduced in the analysis. By the same token, while the role of the EU as a common project that would serve to reduce prejudices―and often it does―the introduction of psychological factors takes away that effect. And finally, our findings only partially justified the cultural capital argument. While there is evidence that would support such a thesis, the uneven migratory experiences and the already argued various heritages across different ethnic groups as tools of acquiring cultural capital suggest that additional research framed within cultural theory, migration hypotheses, and relying on deep qualitative analysis would further clarify such a role. 30 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 References Allport, G.W. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Barrington, L.W. 1997. "Nation and Nationalism": The Misuse of Key Concepts in Political Science. PS: Political Science and Politics 30, 712-717. Bieber, F. (2011). The First Results of the Montenegrin Elections, I Mean Census, are In. At http://fbieber.wordpress.com/blog/ [Accessed October 9, 2011]. Bieber, F. (2003). Montenegrin politics since the disintegration of Yugoslavia. In Montenegro in Transition: Problems of Identity and Statehood, ed. F. Bieber, 11-42. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgelleschaft. Bourdieu, P., and J.C. Passeron. 1979. The Inheritors: French Students and their Relations to Culture. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Brewer, M. B. 2001. Ingroup identification and intergroup conflict: When does ingroup love become outgroup hate? In Social Identity, Intergroup Conflict, and Conflict Reduction, ed. R Ashmore, L Jussim, D Wilder, 17-41. New York: Oxford University Press. Brown, R. and M. Hewstone. 2005. An integrative theory of intergroup contact. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 37, 255-343. Byman, D.L. 2002. Keeping the Peace, Lasting Solutions to Ethnic Conflict. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. Casperen, N. 2003. Elite interests and Serbian-Montenegrin conflict. Southeast European Politics 2-3, 104-121. 31 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 Chirot. D. 2002. Introduction. In Ethnopolitical Warfare: Causes, Consequences, and Possible Solutions, ed. Daniel Chirot and Martin E.P. Seligman, pp 3-26. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. Cook, S. W. (1984). Cooperative interaction in multiethnic contexts. In Groups in contact: The psychology of desegregation, N. Miller and M. B. Brewer, pp. 155-185. Orlando, FL: Academic Press. Diamond, L, & Plattner, M. F. 1994. Introduction. In Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Democracy, eds. Larry Diamond and Marc F. Plattner, ix-xxx. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press. Djilas, Aleksa. 1995. Fear Thy Neighbor: The Breakup of Yugoslavia. In Nationalism and Nationalities in the New Europe, ed. C. Kupchan, 85-106. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. Esman, M.J. 2004. An Introduction to Ethnic Conflict. Cambridge: Polity. Forbes, D. H. 2004. Ethnic Conflict and the Contact Hypothesis. In The Psychology of Ethnic and Cultural Conflict, ed. Yueh-Ting Lee, Clark McCauley, Fathali Moghaddam, and Stephen Worchell, 69-88. Westpoint, CT: Greenwood Publishing Group. Gagnon, Jr., V.P. 1994. Serbia’s Road to War. In Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Democracy, eds. Larry Diamond and Marc F. Plattner, 117-131. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press. Gilley, B. 2004. Against the Concept of Ethnic Conflict. Third World Quarterly 25, 11551166. 32 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 Glenny, M. 1996. The Fall of Yugoslavia: The Third Balkan War. New York: Penguin Books. Hamilton, D. L., & Bishop, G. D. (1976). Attitudinal and behavioral effects of initial integration of White suburban neighborhood. Journal of Social Issues, 32, 47-67. Hearn, J. 2006. Rethinking Nationalism: A Critical Introduction. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Hewstone, M., and R. Brown. 1986. Contact is not enough: An intergroup perspective on the “contact hypothesis.” In Contact and Conflict in Intergroup Encounters, eds. M. Hewstone and R. Brown, 1-44. Cambridge, MA: Basil Blackwell. Huszka, B. (2003). The Dispute Over the Independence of Montenegro. In Montenegro in Transition: Problems of Identity and Statehood, ed. Florian Bieber, 43-62. Baden-Baden: Nomos Verlagsgelleschaft. Jesse, N.G., & Williams, K.P. 2011. Ethnic Conflict: A Systematic Approach to Cases of Conflict. Washington, D.C.: CQ Press. Judah, T. 1997. The Serbs. New Haven: Connecticut: Yale University Press. Kaplan, R. 1996. Balkan Ghosts: A Journey Through History. New York: Vintage Books. Kaufman, Stuart J. 2001. Modern Hatreds: The Symbolic Politics of Ethnic War. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. Lareau, A., and Weininger, E. B. 2003. Cultural Capital in Educational Research: A Critical Assessment. Theory and Society 32(5-6): 567-606. Marushiakova, E., and V. Popov. 2000. Myth as Process. In Scholarship and the Gypsy Struggle. Commitment in Romani Studies, ed. T. Acton, 81-93. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press. 33 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 Mendes, W. B., Blascovich, J., Lickel, B., & Hunter, S. (2002). Challenge and threat during social interaction with White and Black men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 939-952. Oberschall, A. 2002. From Ethnic Cooperation to Violence and War in Yugoslavia. In Ethnopolitical Warfare: Causes, Consequences, and Possible Solutions, ed. Daniel Chirot and Martin E.P. Seligman, 119-150. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. Peshkopia, R. 2010. The Role of Ethnic Divisions in People’s Attitudes toward the Death Penalty: the Case of the Albanians. Paper presented in the 68th Midwest Political Science Association Annual Conference. Chicago, Il., April 22-25. Peshkopia, R. and D.S. Voss. 2010. Attitudes toward the Death Penalty in Ethnically Divided Societies: Albania, Macedonia, and Montenegro. Paper presented in the 68th Midwest Political Science Association Annual Conference. Chicago, Il., April 22-25. Pettigrew, T. F. (1998). Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology 49, 65-85. Pettigrew, T. F, and L. R. Tropp. 2006. A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90, 751-783. Powell, G.B. 1982. Contemporary Democracies: Participation, Stability and Violence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Sells, M. 2003. Crosses of Blood: Sacred Space, Religion, and Violence in Bosnia-Hercegovina. Sociology of Religion 64(3): 309-331. Smith, A. 2001. Nationalism: Theory, Ideology, History. Cambridge: Polity. 34 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 Suberu, R.T. 1995. The Travails of Federalism in Nigeria. In Nationalism, Ethnic Conflict, and Democracy, ed. Larry Diamond and Marc F. Plattner. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University Press. Van Evera, S. 1995. Hypotheses on Nationalism and the Causes of War. In Nationalism and Nationalities in the New Europe, ed. C. Kupchan, 136-157. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. Velikonja, M. 2003. In Hoc Signo Vinces: Religious Symbolism in the Balkan Wars 1991-1995. International Journal of Politics, Culture and Society 17(1): 25-39. Weber, M. 1968. Economy and Society. New York: Bedminster Press. Zimmermann, W. 1996. Origins of a Catastrophe: Yugoslavia and Its Destroyers. Crown. 1 This is not the only case in the former Yugoslavia. As Sells (2003: 310-311) points out in the case of BosniaHercegovina, the features that define nationality and ethnicity did not differ for Bosniaks, Croats and Serbs. 2 The following table borrowed from Florian Bieber (2011) summarizes the percentages of ethnic groups in the Montenegro population over a period of ten years. Table 0. The Percentages of Ethnic Groups in the Population of Montenegro, 1991-2011 Ethnicity Montenegrins 1991 61.84 2003 43.16 2011 44.98 Serbs 9.29 31.99 28.73 7.79 8.65 Bosniaks Muslims 14.6 3.97 3.31 Albanians 6.64 5.03 4.91 Yugoslavs 4.2 0.3 0.19 Croats 1.02 1.1 0.97 As the Table shows, the 1991 census makes no difference between Montenegrins and Serbs, considering all them to be Montenegrins. The rifts emerged during the second half of the 1990s, and ever since have shaped the power struggle in the country. By the same token, the 1991 census did not mention the Bosniak identity and lumped all the Slavic speaking Muslims into the category of Muslims. However, the 2003 census unveiled that the Bosniak identity was more preferable to most of the members of that category, although it is very difficult to find any other reference except from self-declaration that would make the difference between Bosniaks and Muslims, thus consider them as the Bosniak/Muslim category. Other authors (e,g,, Jesse and Williams 2011: 141) have identify Bosnian Muslims as Bosniaks as well. 3 See also the special issues of Journal of Social Issues edited by Zick, Pettigrew, and Wagner (2008: 223-430), and South Africa (see the special issue of Journal of Social Studies edited by Finchilescu and Tredoux (2010: 223-351). 35 Peshkopia: Intergroup Contact Theory and Albanians’ Feeling Temperature toward Greeks Working Paper 006/2013 For an application of the intergroup contact theory to explain heterosexuals’ attitudes toward homosexuals see Herek and Capitanio (1996); for an application of the theory in cases of contacts between healthy and diseased people, see Link and Cullen (1986) and Harper and Wacker (1985). 4 Brown and Hewstone (2005) point out that the reduction of prejudice broadly generated from the contact would include also the group level analysis. 5 Morning times are best for catching household women, who have time to spare while shopping for groceries. Women interviewed during the day also need not answer the questions under the scrutiny of their husbands. 6 In order to gage people's attitude toward a group totally outside of the Balkan context, we asked them of their feeling temperature toward the Argentineans. We used this variable mainly to detect whether respondents were paying attention to the questionnaire and the interviewing process. Their responses brings us to the conclusion that they were reasonably attentive and responsive. Table 2-1 summarizes those responses: Table 2-1. Feeling Temperatures for the Argentineans Among the Ethnic Albanians, Bosniaks, Montenegrins and Serbs Living in Montenegro Feeling Temperatures Albanians Bosniak/Muslims Montenegrins Feeling temperatures for Argentineans Observations: 143 Mean: 19.90 S.D.: 30.81 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 46 Mean: 36.30 S.D.: 46.01 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Observations: 150 Mean: 45.13 S.D.: 38.26 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 7 Serbs Observations: 52 Mean: 30.77 S.D.: 40.29 Min.: 0 Max.: 100 Greece has asserted that it will never recognize the independence of Kosovo unless Serbia recognizes it, while Albania is a strong advocate of Kosovo's independence. 36