Corpora in TS

advertisement

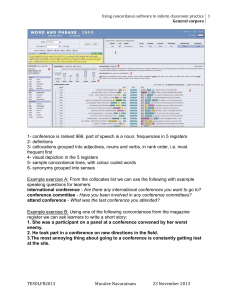

Corpora in TS Corpus linguistics A corpus is a large, more or less principled, possibly annotated, collection of natural texts on computer. It is usually put together for a particular purpose and according to specific design criteria in order to ensure that it is representative of a given area. Notes 'large' may mean anything from 1m. to 200m. words 'principled': based on a principle, e.g. general vs. specialised (in terms of genre, register, subject matter etc.), written vs. spoken, synchronic vs. diachronic (historical), dialect or variant (BrE vs. AmE) 'texts' may be written or spoken (transcribed) or both What are corpora good for? Looking at actual use: how people actually speak, write, translate (performance) Description rather than prescription Natural language rather than formal representations of language Escaping for reliance on native speaker intuition (which may be biased) Variation of language features in relation to other (non-) linguistic features (genre, age, gender) Assessing (relative) frequency Lexicography Terminology – extracting from a representative corpus of authentic texts Use tells us about meaning, e.g. big vs. large vs. great Ensuring all variants of a term are covered Demonstrating their linguistic behaviour and lexical patterns (e.g. collocations from KWIC concordances (key words in context), inc. changes (diachronic) Showing (changes in) frequency of terms Sociolinguistics Intuition on registers, situations etc. unreliable or unavailable e.g. how do doctors speak to patients? Teaching Assessing relative frequency of patterns (and thus order of teaching) e.g. Present Simple vs. Present Continuous Search for translation 'universals' such as explicitation, simplification, levelling etc. Limitations Corpora are always incomplete Selection procedures may bias the sample – what constitutes a 'representative' sample hard to define (e.g. Slovene press – which papers, in what proportions, which parts of the paper etc.) Text fragments may paint a different picture from whole texts Some texts may be unavailable for copyright or other reasons Spoken language much harder to deal with Some features not susceptible to investigation, being hard to detect e.g. ellipsis Nothing can be inferred from non-occurrence in a corpus Frequency and grammaticality are not the same thing (less/fewer people, he might of done it) Occurrence in a corpus may not make an item standard/acceptable Corpora provide facts, but not all facts are significant or interesting A corpus is only a tool, not an end in itself (though it may involve a great deal of work) Types of corpora for translation research Parallel corpora (bilingual) - Original SL texts in language A and their translations in language B - Only as reliable as the translators (e.g. Evroterm) – particularly problematic translations from Slo to Eng - Tell us how translators actually tackle translation problems in practice - Search for translation norms Multilingual corpora - Sets of two or more monolingual corpora using similar design criteria - Study linguistic features/items in home environment (not translations) - Offer insights into behaviour of 'equivalent' items and structures in different languages: help develop teaching materials - Cannot provide answers to theoretical questions in TS - NB: based on the assumption that there is a natural way of saying anything in any language and all we have to do is find it in languages A and B. But: "there are some things that cannot be said naturally in some languages" (Headland 1981 cited in Baker 1995: 233) e.g. Dober tek or Gospa Maja in English, Good afternoon in Slovene - Rather than comparing language A and B, or ST and TT, makes more sense in TS research to compare regular text production with texts produced by translation. > Comparable corpora - Two separate collections of texts in the same language (A): o original texts in language A (monolingual corpus) o translations into language A from a given SL (or SLs) - Both should cover a similar domain, variety of language and time span, and be of comparable length - Helps us identify patterns specific to translated texts or with significantly higher or lower frequency than in original texts (my impressions:…) o e.g. namely over-represented in Slo-Eng translations (from namreč) o e.g. on the one hand … on the other over-represented in Slo-Eng translations o e.g. therefore over-represented in Slo-Eng translations (because of zato) o e.g. organising words like although, nevertheless, furthermore, moreover under-represented in Slo-Eng translations o e.g. phrasal verbs under-represnted in Slo-Eng translations - o Baker's e.g. They claimed/said (that) they would – probably that used more in translations than in original texts Also to support or refute hypotheses about the process of translation Corpus analysis software such as WordSmith can be used to identify a range of textual features that would be laborious or extremely difficult to identify manually: Type/token ratio (see notes on quantitative analysis) Lexical density (ditto) Average word and sentence length Frequency lists - provides statistical evidence for stylistic features such as key words Concordance – a concordancer lists all occurrences of a word and a number of preceding and following words – very helpful when looking for collocations Quantitative analysis Possible lines of research using comparable corpora: 1. Type-token ratio (TTR) To a computer, a sequence of letters with an orthographic space on either side is a word or token. We can say there are x tokens of a particular word, e.g. say, in a given corpus. The word-form say is a type, so we can say there are x tokens of the type say in a corpus of y million words. Corpora can be compared in these terms e.g. Krishnamurthy (1992) overall type-token ration for BBC World Service broadcasts approx. 174 for The Times newspaper approx. 60 (i.e. each type occurs on average 174 times rather than 60). Thus the former more lexically restricted than the latter – explainable by spoken-written difference?) Comparing translations with non-translations we may find a higher type-token ratio and thus evidence of lexical simplification. type-token ratio n. In the study of texts, the ratio of the number of different words, called types, to the total number of words, called tokens. For example, in a particular text, the number of different words may be 1,000 and the total number of words 5,000, because common words such as the may occur several times, and in this case the type-token ratio would be 1/5 or 0.2. Used for investigating e.g. child language acquisition 2. Lexical density Lexical words have 'content' – nouns, adjectives and verbs Grammatical words organise language – prepositions, determiners, pronouns Lexical density = percentage of lexical vs. grammatical words in a corpus Lexical density of written English higher than spoken: the former is edited, redrafted, repetition and redundancy cut; the latter has more contextual clues, has to be interpreted in real time. Lexical words belong to open sets therefore less predictable 'Difficult' texts have higher lexical density and information load. Is lexical density of translations lower than originals?