Ethnic Banking: Turkish Immigrants In Berlin

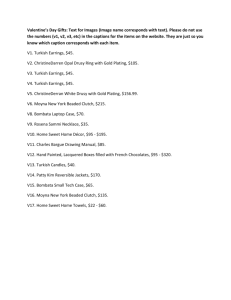

advertisement