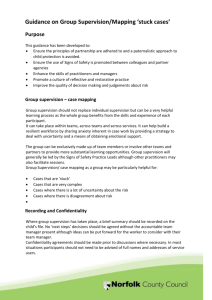

Leading practice a resource guide for child protection leaders

advertisement