vertigo - developinganaesthesia

advertisement

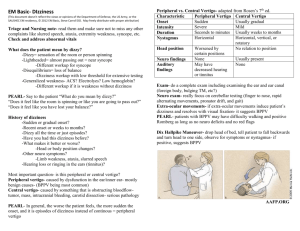

VERTIGO “Relativity”, M.C Escher, Lithograph 1953 Albert Einstein’s theories of relativity showed that the physical world as it appears to us is not always what it seems, it depends on your vantage point. Time for example is not a constant entity, it depends on your speed of travel and at the speed of light it stands still! Patients’ complaints of “dizziness” rarely imply true vertigo. Like the passage of time in relation to velocity patients will interpret “dizziness” in relation to their own frame of reference and understanding of what this means. It is important therefore to establish precisely what a patient means when they complain of the symptom of dizziness. VERTIGO Introduction Vertigo is a false perception of motion. Patients will frequently complain of “dizziness”, however, this is a virtually meaningless lay term, (similar to “hot and cold flushes”). It may mean true vertigo or it may refer to “presyncopal” symptoms. In the elderly non English speaker especially it may simply mean, “I feel unwell.” It is important therefore to establish exactly what the patient means by “dizziness”. In true vertigo there is a perception that the environment or patient is spinning around. Vertigo is generally divided into peripheral or central causes. A major initial decision that needs to be made in ED presentations will be whether or not cerebral imaging is required. Traditionally clinical rules-of-thumb have been used to distinguish central from peripheral lesions. The frequent assumption is then made that a peripheral cause is “benign” and doesn’t require imaging. However it is essential to appreciate the following: ● These clinical rules are not definitively reliable, (many cases of central vertigo are labeled “peripheral” vertigo on purely clinical grounds - which later prove not to be the case - with suboptimal outcomes resulting). ● Not all causes of peripheral vertigo are necessarily benign! The decision to proceed with imaging should be made not only on the basis of the clinical findings, but also on the basis of a patient’s individual risk profile for vascular disease. CT scan is often used as the imaging modality for vertigo because of its ready availability. This however is at best a “screening” investigation. If symptoms persist, or are severe enough or the patient’s risk profile high enough, then CT angiogram will be a better investigation, and MRI/MRA will be the best investigation of all. Treatment is directed at the symptoms as well as the underlying cause. Pathophysiology The sense of spatial orientation: The sense of spatial orientation depends on: ● Visual input. ● Labyrinthine input. ● Proprioceptive input. This information is then centrally processed in the cerebellum, brainstem, basal ganglia and ultimately the cerebral cortex (temporal and parietal regions) A patient’s sense of spatial orientation may therefore be affected by a lesion in any of these regions. However only a vestibular (labyrinthine) lesion will result in true vertigo. The mechanism of nystagmus: The mechanism of peripheral nystagmus involves a slow and a quick phase. The slow phase (vestibulo-ocular reflex) is a relatively slow drift toward the side with the (ablative) lesion. The quick phase is a cortex controlled quick corrective movement back in the opposite direction. Therefore nystagmus has a quick phase away from the affected side. The direction of a nystagmus is named for the direction of the quick component. In peripheral vertigo the patient may feel that either they are moving or that the environment is moving. They may feel that the environment is spinning in the direction of the fast component or that their body is spinning in the direction of the slow component. Vestibular nystagmus occurs in the plane of the affected semicircular canal and can be either horizontal or torsional-vertical. Strictly vertical nystagmus is rarely the result of vestibular involvement and usually means a brainstem lesion. Causes of Vertigo: These are traditionally divided into peripheral and central causes. Peripheral Vertigo (no CNS signs discernable) No associated deafness or tinnitus: ● Benign positional vertigo. ● Vestibular neuronitis. Associated deafness or tinnitus: ● Labyrinthitis, (viral or more seriously but rarely bacterial) ● Ototoxic drugs (aspirin, aminoglycosides, frusemide quinine) ● Meniere’s disease. ● Acoustic neuroma ● Internal auditory small artery disease. (See also Appendix 1 below for notes on peripheral causes) Central Vertigo: (usually - but not always - with associated CNS, brainstem or cerebellar signs) ● Vascular: Posterior fossa, i.e. brain stem or cerebellar lesions ♥ Ischemia, (e.g. cerebellar or lateral medullary syndrome or variations thereof) ♥ Hemorrhagic lesions ♥ Migraine variants. Less commonly: ● Central space occupying lesions ● Demyelination lesions. ● CNS infection (encephalitis, abscess or meningitis) Clinical assessment It is important from the outset to carefully establish what the patient means by their complaint of vertigo or “dizziness” The main differential in this regard will usually be from orthostatic hypotension - a completely different problem to vertigo!, (see separate guidelines on orthostatic hypotension) Vertigo is also strongly associated with: ● Nausea/ retching, ● Vomiting. ● Pallor and sweating. As general rules of thumb clinical assessment can help distinguish a peripheral cause of vertigo from a central cause according to the following table: Peripheral Central Symptoms are intense often with nausea and vomiting Symptoms are less well defined Very position dependent Not positionaly related No associated CNS signs (apart from the 8th cranial nerve - hearing loss or tinnitus) May be associated with other CNS signs, brainstem or cerebellar, (but also may not): ● Ataxia or other cerebellar signs ● Visual loss ● Brainstem symptoms: ● ♥ Diplopia ♥ Dysarthria ♥ Dysphagia Long tract signs, weakness or hemisensory Fatigable unidirectional nystagmus Non fatigable multidirectional nystagmus Nystagmus is inhibited by ocular fixation Nystagmus is not inhibited by ocular fixation Conscious state not affected Confusion / altered conscious state The above signs however do not always reliably differentiate central from peripheral causes, and it is important to also take into consideration a patient’s risk profile for CVS disease, as vertebrobasilar insufficiency is an important condition that should not be missed. Note that in elderly patients, non English speaking patients, cognitively impaired patients, and/or very distressed patients accurate clinical neurological examination may be very difficult if not impossible. Important risk factors for central vascular disease will include the usual risk factors for CVS disease in general such as: ● Age ● Hypertension ● Smoking ● Diabetes ● Hypercholesterolemia ● AF/ A. flutter ● PVD ● Known carotid / cardiac disease, (CAGS/coronary stents). In addition the persistent inability of a patient to walk is an important clue that the problem may relate to a central lesion. See also appendix 1 below for clinical features of peripheral conditions causing vertigo. Once a diagnosis of peripheral vertigo is made it is important to try to further distinguish between the two commonest causes, BPPV and vestibular neuronitis as the treatments for these are different. A positive Dix-Hallpike test will help confirms the diagnosis of BPPV. Investigations These will be guided according to the index of suspicion for any given condition. The following will need to be considered: Blood tests: ● FBE ● U&Es / glucose ECG: ● For the documentation of cardiac disease including arrhythmias such as AF or atrial flutter. Imaging In younger patients with clear features of peripheral vertigo routine imaging is not generally necessary. If central vertigo is suspected, then imaging is required. CT scan is not the best investigation but is readily available and is a useful examination to exclude the important condition of a posterior fossa hemorrhage. If no hemorrhage is seen, consideration should be given to a follow up contrast angiogram study in those at high risk of vertebrobasilar insufficiency. MRA/MRI is the ideal investigation for vertigo of both peripheral and central causes. Note that in elderly patients, non English speaking patients, cognitively impaired patients, and/or very distressed patients accurate neurological examination may be very difficult if not impossible. A lower threshold for imaging should be maintained for elderly patients or those with risk factors for cerebrovascular disease. These patients have a higher risk for a central cause of vertigo, even when no other symptoms manifest. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis it is best to admit these patients and arrange for a CT scan/ MRI to rule out a central lesion, (such as lateral medullary infarction or variants thereof) CT Scan Brain: This is not the ideal modality for the investigation of peripheral or central vertigo, yet is often undertaken simply because of its ready availability. Its predominate utility is the ruling out of a posterior fossa hemorrhage and is useful for this indication, as well as being a very important cause to rule out. CT Angiogram: This is a better imaging modality than plain CT scan, in cases of vascular ischemic disease. It should be considered as a follow-up to CT with has excluded a hemorrhage, in patients who are at high risk for vertebrobasilar disease. It delineates the carotid and vertebral vessels and provides a probable diagnosis where high grade stenosis exists. MRA/MRI: This is the best imaging modality for patients being investigated for vertigo. It should be done for patients who are suspected of having vertebrobasilar insufficiency in the form of TIAs or completed stroke. It will provide valuable information of the state of the carotid and vertebral circulations. It will also provide information about areas of established infarction (and hence give a definitive diagnosis) which CT cannot provide. It is the best imaging investigation for middle and inner ear pathology as well as for acoustic neuromas. Management There are 4 important considerations when planning the management and disposition of the patient who presents to the Emergency Department with “vertigo”. ● Control of the patient’s symptoms ● Deciding on the need for imaging, and what type of imaging ● Treatment of the underlying cause of the vertigo, (where possible). ● The disposition of the patient Symptomatic treatment Treatment of symptoms include: 1. IV fluids: ● 2. 3. If there has been prolonged nausea and vomiting and/or an ongoing inability to tolerate oral fluids. Antiemetics: ● Prochlorperazine ● Ondansetron/ granisetron Diazepam: This can be an additional option for those with severe symptoms ● Diazepam 5 to 10 mg orally, 3 times daily. 2 ● 4. Small titrated IV doses may be considered for very severe symptoms, in those who cannot tolerate anything orally. Promethazine ● This is also an alternative option to help alleviate severe symptoms See latest Therapeutic Guidelines for full prescribing details. Note that the long-term daily symptomatic treatment of chronic dizziness or vertigo with the above drugs is not recommended due to the risk of tardive dyskinesia, drug-induced parkinsonism and dependence. 2 Treatment of the underlying cause Where possible specific treatment is directed to the underlying cause. Antiplatelet agents are given in cases of ischemic vertebrobasilar insufficiency Cases of benign peripheral vertigo can often be helped with mechanical maneuvers. Cases of vestibular neuronitis should receive corticosteroids. Disposition This will obviously depend on the cause of the vertigo as well as the severity of the symptoms. All cases of central or suspected central vertigo should admitted for ongoing assessment Younger patients with benign causes of peripheral vertigo may be able to be treated as outpatients. If symptoms are severe in peripheral causes of vertigo and/ or there are significant comorbidities admission to hospital will be necessary. If there is associated acute hearing loss, this may not be simple “peripheral vertigo” and these cases should be discussed with ENT, before discharge, (see also Acute Hearing Loss guidelines). Appendix 1 Features of peripheral conditions leading to vertigo Benign positional vertigo: 1. Repeated attacks of vertigo, which are strongly precipitated by changes in posture, (cf neuronitis which is more severe and constant, though still somewhat aggravated by movement). 2. No hearing loss or tinnitus. 3. Common and usually in the elderly. 4. Attacks are short lived, lasting seconds to minutes only. They usually subside over several weeks, (cf neuronitis which lasts days to weeks) 5. Hallpike’s test helps to confirm the diagnosis. See also separate guidelines. Vestibular neuronitis: 1. Acute onset of peripheral vertigo with severe associated symptoms. 2. Vertigo comes on spontaneously and persists at rest. There may be some aggravation with movement but this is not as strong as that seen in BPPV. 2. Tinnitus may occur though there is no hearing loss. 3. Lasts days to weeks. 4. Presumed viral origin. Labyrinthitis: This is a less common and more severe condition than vestibular neuronitis. 1. Acute onset of peripheral vertigo with severe associated symptoms. 2. There is hearing loss. 3. Possible viral origin, rarely a bacterial infection. 4. May be secondary to a traumatic perilymph fistula. Meniere’s disease: 1. Uncommon, usually in the elderly over 50 years of age. 2. Recurrent attacks of severe vertigo, lasting 30 minutes up to 12 hours. There may be periods of weeks to years between attacks. 3. There is a progressive background of tinnitus and deafness. 4. The intensity of attacks generally diminishes and finally ceases as the deafness progresses. Acoustic neuroma: 1. This is a rare neurofibroma of the 8th cranial nerve. 2. Commonest age group is 35-45 years of age. 3. There is a progressive deafness, sometimes with a mild tinnitus and vertigo. 4. The lesion may progress to cause pressure on adjacent structures within the cerebello-pontine angle to produce: ● 7th cranial nerve lesion. ● 5th cranial nerve lesion: ♥ Weakness of mastication ♥ Loss of corneal reflex. ♥ Facial sensory loss. ● 6th cranial nerve lesion. ● Ipselateral cerebellar signs. References 1. Strupp M et al. Methylprednisolone, Valacyclovir, or the Combination for Vestibular Neuritis. N Engl J Med July 2004; 351:354-61. 2. Neurology Therapeutic Guidelines, 4th ed, 2011. Dr J Hayes Reviewed 6 September 2012