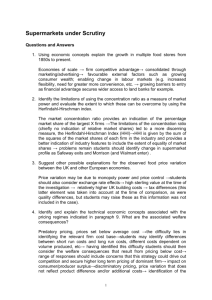

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN MARKETS IN DEVELOPING

advertisement