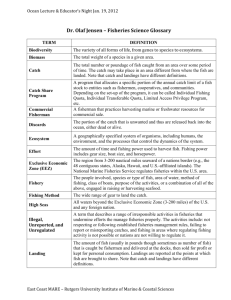

The Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act

advertisement