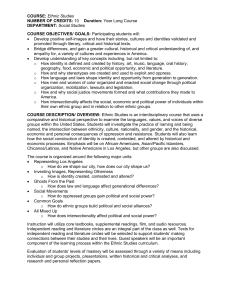

Saui Newman, “Does modernization breed ethnic political conflict

advertisement

Session 10 Saui Newman, “Does modernization breed ethnic political conflict?, World Politics, April 1991, pp. 451-78 In this article the author attempts to explain ethnic conflict by conflictual modernization approach and test its utility by examining ethnic political conflict in Western Europe and North America since the late 1960s. This approach can do more than identify the variables that give rise to ethnic political movements and can be used to explain and analyze the ideologies and organizations of ethnic political movements. Ethnicity; from “Primordial” obligation to modern identification Marx’s or Durkheims melting pot modernization approach (e.g. as modernization proceeds, ethnic identification will disappear) was empirically denied by ethnic political conflicts not only in the developing world but also in the industrialized world (e.g. Quebec, Scotland, Wales and Belgium) Walker Connor argued that the process of economic modernization does not undermine ethnic divisions but invigorates them by bringing together previously isolated ethnic groups that suddenly find themselves compete for the same economic niches. Ethnicity became seen as an identity that could be constantly created and re-created to suit particular political goals. But how? Explaining the ethnic “Revival”; building on the conflictual modernization approach Anthony Smith applies Connor’s approach in accounting for ethnic political activity, arguing that potential bureaucrats who were dissatisfied with modern state setting returned to their ethnic group to lead ethnic political movements. This theory, however, has three flaws; i) too much left unexplained, such as definition of ethnicity, ii) failure to solidify the connection between modernization and ethnic identities, and iii) lack of explanations why the elites could mobilize mass support. Reworking the conflictual modernization paradigm By the 1980s the popular theories (the modernization approach/the conflictual modernization approach) failed in explaining ethnic political conflicts. Joseph Rotheshild’s conflictual modernization approach includes ethnic groups and the state as actors with economic and political resources at their disposal. He claims that the sufficient condition for ethnic political movements are dependent on the economic, political, and ideological resources available to ethnic groups. Edward Tiryakian and Ronald Rogowski’s conflictual modernization approach depends on “rational choice theory” to predict when ethnic identities will result in political conflict. Depending on the balance of resources available to the various ethnic groups within the states, individuals from each type of ethnic group within a state react to ethnic group dominance---whether by assimilation, isolation, apathy, resistance, or minority nationalism. some internal inconsistency. Despite its contributions, Togowski’s theory holds Rational choices made by ethnic elites are not necessarily national choices for mass supporters. A new approach; the psychological dynamic Donald Horowits’s new approach emphasizes on “ethnic dynamic”, a psychological dynamic that underlies the relationship between the causes of conflict, the development of an ethnic agenda, and the consequent permutations that these conflicts undergo. Ethnic identity is unique in that one can maneuver out of one’s ethnic identity, while class mobility is 1 possible. In ranked ethnic systems, where mobile opportunities are restricted by group identity, ethnic conflict will most likely take the form of a social revolution with emphasis of class divisions rather than ethnicity. Unranked ethnic systems, where parallel ethnic groups coexist and each group is internally stratified, have the potential for erupting into ethnic conflict. Here evaluations of other ethnic groups, such as advanced or backward, (advanced by the colonialism) became conceptualization of ethnic difference penetrating into governmental policy. This psychological dynamic feeds ethnic conflict at all strategies and can determine the direction of ethnic conflict and ethnic political movements. The limitation of this theory is i) rejection of economic explanations for the rise of ethnic conflict, ii) failure in explaining in conflict in ranked systems (South Africa) and in developed world. Re-creating “Primordial ” identities The manner in which modernization politicizes ethnic identifications should be more focused, as in religious political movement and recreation of religious identity. Juan Linz examines the recreation of ethnic identities and ethnic agendas, arguing that traditional ethnic nationalists movements generally advocate primordial conceptions of nationalism rooted in common ancestry and the use of common ethnic instruments such as language. Over time, however, the processes ethnic intermarriage and migration make these primordial sentiments increasingly anachronistic. As a result, ethnic nationalist turn to a territorial conception of ethnicity in their drive for regional autonomy that would be inclusive of those who do not fit the primordial qualification of ethnicity. These movements have no unique ethnic character when compared with other autonomy movements, which again turns to primordial elements to reinforce its distinctiveness. Residents who are not members of the majority ethnic group are forced to assimilate or challenge the ideology of the leadership of the ethnic movements. Expanding modernization approach: the re-creation process The author argues in the case of ethnic political movement in Quebec and other cases by exploring re-creation process of ethnic identities. Social, economic and political modernization can account for more than the necessary condition for the rise of ethnic conflict. Conclusion By emphasizing the ideological component of ethnicity, this new approach addresses the reasons for mass participation in ethnic movement, brings an ethnic component to the study of ethnic politics, and expands the purview of the conflictual modernization approach. 2