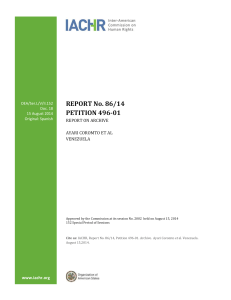

Garífuna Community of “Triunfo de la Cruz” and its Members

advertisement