Benzodiazepines (not including sedative/hypnotics*)

advertisement

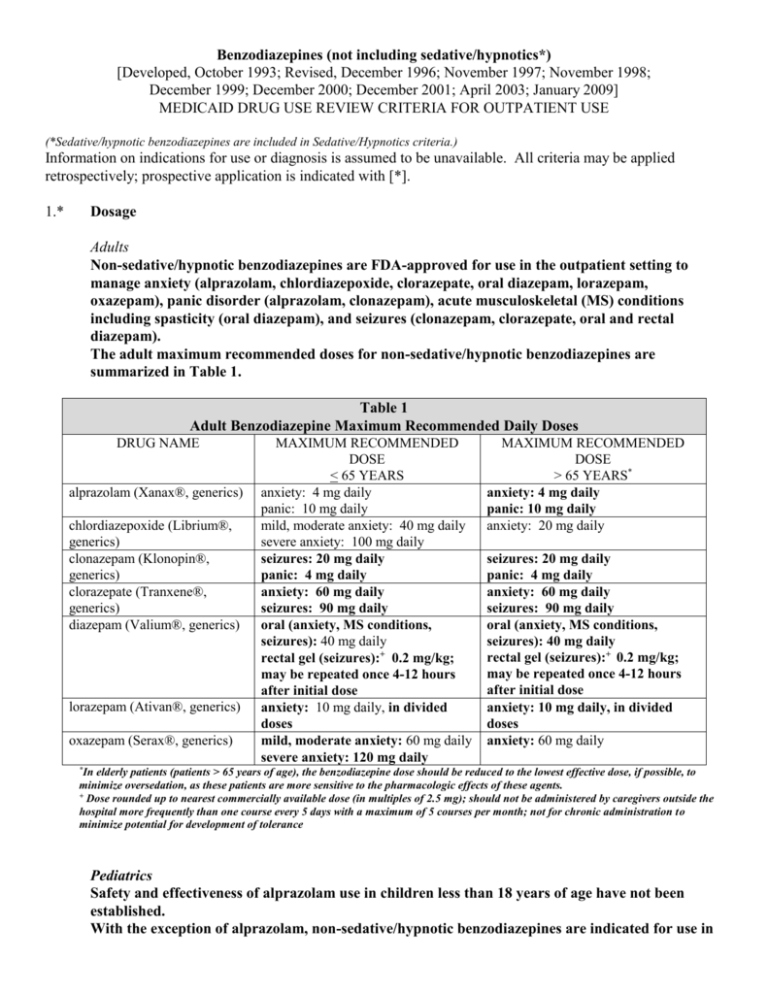

Benzodiazepines (not including sedative/hypnotics*) [Developed, October 1993; Revised, December 1996; November 1997; November 1998; December 1999; December 2000; December 2001; April 2003; January 2009] MEDICAID DRUG USE REVIEW CRITERIA FOR OUTPATIENT USE (*Sedative/hypnotic benzodiazepines are included in Sedative/Hypnotics criteria.) Information on indications for use or diagnosis is assumed to be unavailable. All criteria may be applied retrospectively; prospective application is indicated with [*]. 1.* Dosage Adults Non-sedative/hypnotic benzodiazepines are FDA-approved for use in the outpatient setting to manage anxiety (alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clorazepate, oral diazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam), panic disorder (alprazolam, clonazepam), acute musculoskeletal (MS) conditions including spasticity (oral diazepam), and seizures (clonazepam, clorazepate, oral and rectal diazepam). The adult maximum recommended doses for non-sedative/hypnotic benzodiazepines are summarized in Table 1. Table 1 Adult Benzodiazepine Maximum Recommended Daily Doses DRUG NAME alprazolam (Xanax®, generics) chlordiazepoxide (Librium®, generics) clonazepam (Klonopin®, generics) clorazepate (Tranxene®, generics) diazepam (Valium®, generics) lorazepam (Ativan®, generics) oxazepam (Serax®, generics) MAXIMUM RECOMMENDED DOSE < 65 YEARS anxiety: 4 mg daily panic: 10 mg daily mild, moderate anxiety: 40 mg daily severe anxiety: 100 mg daily seizures: 20 mg daily panic: 4 mg daily anxiety: 60 mg daily seizures: 90 mg daily oral (anxiety, MS conditions, seizures): 40 mg daily rectal gel (seizures):+ 0.2 mg/kg; may be repeated once 4-12 hours after initial dose anxiety: 10 mg daily, in divided doses mild, moderate anxiety: 60 mg daily severe anxiety: 120 mg daily MAXIMUM RECOMMENDED DOSE > 65 YEARS* anxiety: 4 mg daily panic: 10 mg daily anxiety: 20 mg daily seizures: 20 mg daily panic: 4 mg daily anxiety: 60 mg daily seizures: 90 mg daily oral (anxiety, MS conditions, seizures): 40 mg daily rectal gel (seizures):+ 0.2 mg/kg; may be repeated once 4-12 hours after initial dose anxiety: 10 mg daily, in divided doses anxiety: 60 mg daily *In elderly patients (patients > 65 years of age), the benzodiazepine dose should be reduced to the lowest effective dose, if possible, to minimize oversedation, as these patients are more sensitive to the pharmacologic effects of these agents. + Dose rounded up to nearest commercially available dose (in multiples of 2.5 mg); should not be administered by caregivers outside the hospital more frequently than one course every 5 days with a maximum of 5 courses per month; not for chronic administration to minimize potential for development of tolerance Pediatrics Safety and effectiveness of alprazolam use in children less than 18 years of age have not been established. With the exception of alprazolam, non-sedative/hypnotic benzodiazepines are indicated for use in pediatric patients to provide sedation, or manage anxiety or seizures. Pediatric dosages and age limitations for benzodiazepines are summarized in Table 2. Table 2 Pediatric Benzodiazepine Maximum Recommended Dosages DRUG NAME chlordiazepoxide clonazepam clorazepate diazepam lorazepam oxazepam MAXIMUM RECOMMENDED DOSE anxiety: > 6 years of age: 30 mg daily in divided doses, or 0.5 mg/kg daily in divided doses seizures: < 10 years of age or < 30 kg: 0.2 mg/kg daily in divided doses > 10 years of age or > 30 kg: 20 mg daily in divided doses seizures: 9-12 years: 60 mg daily in divided doses > 12 years of age: 90 mg daily in divided doses oral (sedation, MS conditions, seizures): > 6 months of age: 0.8 mg/kg/day in divided doses; alternately, for seizures, 30 mg daily in divided doses rectal gel (seizures):+ 2-5 years of age: 0.5 mg/kg/dose 6-11 years of age: 0.3 mg/kg/dose > 12 years of age: 0.2 mg/kg/dose anxiety, sedation: > 12 years of age: 10 mg daily in divided doses (maximum, 2 mg/dose4) anxiety: 6-12 years of age: dose not established; 1 mg/kg/day has been adequate5 > 12 years of age: 30-90 mg daily6-8 +Dose rounded up to nearest commercially available dose (in multiples of 2.5 mg); should not be administered by caregivers outside the hospital more frequently than one course every 5 days with a maximum of 5 courses per month; not for chronic administration to minimize potential for development of tolerance 2. Duration of Therapy Anxiety disorders are considered chronic disorders with low spontaneous remission rates and high rates of relapse. Pharmacotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) in adults includes antidepressants, benzodiazepines, buspirone, hydroxyzine and pregabalin. Treatment duration for GAD ranges from 3 months to 12 months to accomplish treatment goals of symptom remission and improvement in quality of life. Although antidepressants are now considered drugs of choice for managing GAD, benzodiazepines are used frequently for short-term management of anxiety, as an adjunct to initiating antidepressant therapy, or improvement in sleep disturbances associated with GAD and/or antidepressant therapy. Benzodiazepines provide symptom improvement more rapidly than antidepressants and are more effective in managing somatic complaints rather than psychic symptoms. Although longer-term use is considered relatively safe and effective for benzodiazepines, the potential for abuse, dependence and withdrawal does exist. In pediatric patients, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are agents of choice to manage childhood anxiety disorders, with benzodiazepines prescribed as alternatives either alone or concurrently with accepted antidepressant therapy. Panic disorder (PD) is a chronic, recurring condition requiring drug therapy suitable for prolonged use. The acute treatment phase for PD lasts approximately 12 weeks, and most patients require an additional 12to 18 months of therapy to optimize treatment response and prevent relapse. SSRIs are the agents of choice to manage PD, although benzodiazepines are frequently prescribed as well, usually in combination with antidepressant therapy. While benzodiazepines are effective in the short-term treatment of panic disorder due to rapid onset of action, long-term treatment may be less desirable due to the potential for dependence. Unlike anxiety disorder patients, patients with panic disorder are less successful at discontinuing benzodiazepine therapy. Additionally, there is a high prevalence of comorbid depression and/or bipolar disorder in patients with panic disorder. Benzodiazepines are less effective than other available agents when panic disorder coexists with other mood disorders. Therefore, patients with panic disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities may benefit from short-term therapy with a benzodiazepine, with chronic management incorporating mood stabilizing or antidepressant agents that are also effective in panic disorder. Alprazolam has been studied more than other available benzodiazepines for the treatment of panic disorder, although clonazepam, lorazepam, and diazepam have also been evaluated. Most studies evaluating benzodiazepine use in panic disorder have been short-term studies (< 8 weeks in duration). A few longterm panic disorder studies evaluating alprazolam have demonstrated sustained reductions in panic attack frequency when alprazolam has been administered for 6 to 8 months. Benzodiazepines should be tapered when discontinued, as patients may experience a withdrawal syndrome if therapy is discontinued abruptly. Benzodiazepine elimination half-life and seizure history for the patient also influence the taper duration. Patients receiving benzodiazepines in lower doses for shorter times periods (less than six months) may be effectively tapered over two to eight weeks, while patients receiving benzodiazepines with a short elimination half-life, in higher doses, and/or for a longer duration (six months or longer) may require a slow taper over two to four months. Benzodiazepines are prescribed on a short-term basis to manage anxiety disorders. Patient profiles documenting benzodiazepine use for anxiety lasting greater than four months will be reviewed. While concerns for benzodiazepine tolerance and withdrawal exist, patients may benefit from long-term use of benzodiazepines in panic disorder to minimize symptom recurrence. Additionally, significant problems with benzodiazepine dose escalation have not surfaced with chronic use for panic disorder. The use of benzodiazepines as an anti-epileptic is not limited in duration. 3.* Duplicative Therapy The combined use of two or more benzodiazepines is not supported in the literature and therefore is not recommended. The concurrent use of two or more benzodiazepines will be reviewed. 4.* Drug-Drug Interactions Patient profiles will be assessed to identify those drug regimens which may result in clinically significant drug-drug interactions. The following drug-drug interactions are considered clinically relevant for benzodiazepines. Only those drug-drug interactions identified as clinical significance level 1 or those considered life-threatening which have not yet been classified will be reviewed: a. Select CNS Depressants [clinical significance level – major (DrugReax); buprenorphine, opioid analgesics: 1 (DIF)] Concurrent administration of benzodiazepines with opioid analgesics, buprenorphine, chloral hydrate, barbiturates, or centrally acting skeletal muscle relaxants may result in potentiation of respiratory depression. Patients requiring concurrent therapy with benzodiazepines and CNS depressants should be monitored for respiratory depression; dosages should be modified as necessary. Concurrent administration of benzodiazepines with buprenorphine may also increase the risk of cardiovascular collapse. Concurrent administration of benzodiazepines with buprenorphine is not recommended and will be reviewed. b. Benzodiazepines (oxidized) and Protease Inhibitors [e.g., indinavir (Crixivan®), ritonavir (Norvir®)] [clinical significance level – alprazolam and indinavir: contraindicated (DrugReax); other benzodiazepines and protease inhibitors: moderate (DrugReax); 1 (DIF)] Concurrent administration of benzodiazepines that undergo oxidative metabolism with protease inhibitors may result in enhanced benzodiazepine pharmacologic effects and/or risk of toxicity. Patients may experience significant sedation and potentially respiratory depression when this drug combination is utilized. Protease inhibitors inhibit hepatic metabolism of those benzodiazepines subject to oxidative metabolism including alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, clorazepate, and diazepam. When concurrent administration of protease inhibitors and benzodiazepines is necessary, a benzodiazepine metabolized by glucuronidation (e.g., oxazepam) may be considered. Adjuvant administration of protease inhibitors and benzodiazepines that undergo oxidative metabolism is not recommended and will be reviewed. c. Benzodiazepines (oxidized) and Azole Antifungals [clinical significance level –alprazolam and itraconazole: contraindicated (DrugReax); other benzodiazepines and itraconazole: major (DrugReax); 2 (DIF); 3 (Hansten & Horn)] The combined use of azole antifungals and benzodiazepines which undergo oxidative metabolism, such as alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, and diazepam may result in elevated serum benzodiazepine levels and enhanced or prolonged CNS depression. It is presumed that itraconazole, fluconazole, and ketoconazole inhibit metabolism of oxidized benzodiazepines at the cytochrome P450 3A4 isozyme site. Concurrent use of azole antifungals and benzodiazepines that undergo oxidative metabolism is not recommended and will be reviewed. When adjunctive azole antifungal and benzodiazepine treatment is necessary, a lower benzodiazepine dose or a benzodiazepine metabolized by glucuronidation (e.g., oxazepam) may be considered. d. Benzodiazepines (oxidized) and Macrolide Antibiotics [e.g., clarithromycin (Biaxin®), erythromycin, telithromycin (Ketek®)] [clinical significance level – moderate (DrugReax); 2 (DIF); 3 (Hansten & Horn)] The combined use of certain macrolide antibiotics and benzodiazepines which undergo oxidative metabolism, such as alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, and diazepam may result in elevated serum benzodiazepine levels and enhanced or prolonged CNS depression. It is presumed that clarithromycin and erythromycin inhibit metabolism of oxidized benzodiazepines at the cytochrome P450 3A4 isozyme site. Concurrent use of these macrolide antibiotics and benzodiazepines that undergo oxidative metabolism is not recommended and will be reviewed. When adjunctive macrolide and benzodiazepine treatment is necessary, a lower benzodiazepine dose or a benzodiazepine metabolized by glucuronidation (e.g., oxazepam) may be considered. Alternately, azithromycin does not significantly interfere with CYP3A4 metabolism and may be a suitable alternative in patients prescribed benzodiazepines requiring macrolide antibiotics. e. Alprazolam and Delavirdine (Rescriptor®), Efavirenz (Sustiva®) [clinical significance level – contraindicated (DrugReax); 2 (DIF)] Combined administration of alprazolam and non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTs) such as delavirdine and efavirenz may result in inhibition of alprazolam metabolism and the potential for serious and/or life-threatening events, including prolonged sedation and respiratory depression. NNRTs inhibit the cytochrome P450 3A4 isoenzyme and compete with alprazolam for metabolism by this enzyme, which results in increased serum alprazolam concentrations. Combined administration of alprazolam and NNRTs is not recommended and will be reviewed. REFERENCES 1. Klasco RK (Ed): DRUGDEX® System (electronic version). Thomson Micromedex, Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. Available at : http://www.thomsonhc.com. Accessed January 26th, 2009. 2. AHFS drug information 2008 [book online]. Jackson, WY: Teton Data Systems, Version 5.9.0, 2009. Based on: McEvoy GK, editor. AHFS drug information 2008. Bethesda (MD): American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; 2008. Stat!Ref Electronic Medical Library. 3. Drug facts and comparisons. Facts and Comparisons 4.0 [database online]. St. Louis, MO: Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.; 2009. Available at: http://online.factsandcomparisons.com. Accessed January 26th, 2009. 4. Custer JW, Rau RE, eds. Harriet Lane handbook. 18th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2009. 5. Deberdt R. Oxazepam in the treatment of anxiety in children and the elderly. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1978;274:104-10. 6. Witek MW, Rojas V, Alonso C, Minami H, Silva RR. Review of benzodiazepine use in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Q. 2005;76(3):283-96. 7. Kersun LS, Shemesh E. Depression and anxiety in children at the end of life. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2007;54:691-708. 8. Cummings MR, Miller BD. Pharmacologic management of behavioral instability in medically ill pediatric patients. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16:516-22. 9. Drug interaction facts. Facts and Comparisons 4.0 [database online]. St. Louis, MO: Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.; 2009. Available at: http://online.factsandcomparisons.com. Accessed January 27th, 2009. 10. Hansten PD, Horn JR, eds. Hansten and Horn’s drug interactions analysis and management. St. Louis, MO: Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc.; 2009. 11. Klasco RK (Ed): Drug-Reax® System (electronic version). Thomson Micromedex, Greenwood Village, Colorado, USA. Available at: http://www.thomsonhc.com.libproxy.uthscsa.edu. Accessed January 27th, 2009. 12. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Drugs@FDA. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/. Accessed January 27th, 2009. 13. Kirkwood CK, Melton ST. Anxiety disorders I. Generalized anxiety, panic, and social anxiety disorders. In: DiPiro JT, Talbert RL, Yee GC, Matzke GR, Wells BG, Posey LM, eds. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach. 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008:1161-78. 14. Work Group on Panic Disorder. American Psychiatric Association Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, second edition. Available at: http://www.psychiatryonline.com/pracGuide/pracguideChapToc_9.aspx. Accessed January 27th, 2009. 15. Schweizer E, Rickels K, Weiss S, Zavodnick S. Maintenance drug treatment of panic disorder. I. Results of a prospective, placebo-controlled, comparison of alprazolam and imipramine. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:51-60. 16. Kasper S, Resinger E. Panic disorder: the place of benzodiazepines and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2001;11:307-21. 17. Katon WJ. Panic disorder. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(22):2360-7. 18. Schneier FN. Social anxiety disorder. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(10):1029-36. 19. Hoffman EJ, Mathew SJ. Anxiety disorders: a comprehensive review of pharmacotherapies. Mt. Sanai J Med. 2008;75:248-62. 20. Botts S, Bettinger T, Greenlee B. Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder. In: Chisholm-Burns MA, Wells BG, Schwinghammer TL, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy: principles and practice. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008:605-619. 21. Connolly SD, Bernstein GA, and the Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(2):267-83. Prepared by: Drug Information Service, The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, and the College of Pharmacy, The University of Texas at Austin.