Karen Hearn

advertisement

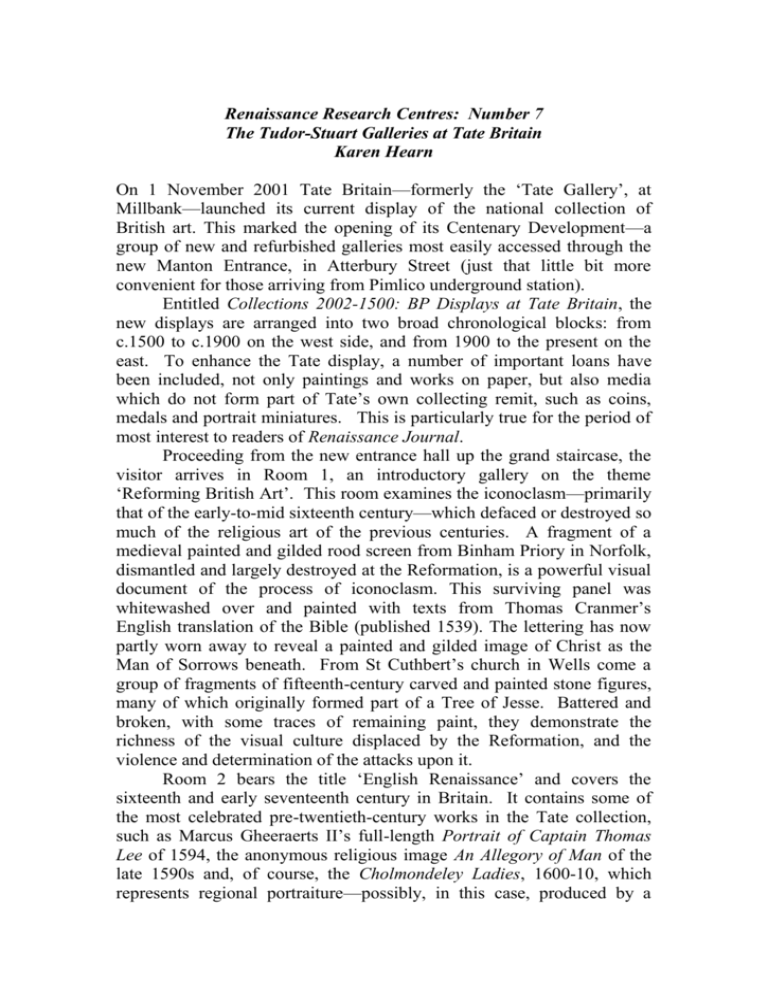

Renaissance Research Centres: Number 7 The Tudor-Stuart Galleries at Tate Britain Karen Hearn On 1 November 2001 Tate Britain—formerly the ‘Tate Gallery’, at Millbank—launched its current display of the national collection of British art. This marked the opening of its Centenary Development—a group of new and refurbished galleries most easily accessed through the new Manton Entrance, in Atterbury Street (just that little bit more convenient for those arriving from Pimlico underground station). Entitled Collections 2002-1500: BP Displays at Tate Britain, the new displays are arranged into two broad chronological blocks: from c.1500 to c.1900 on the west side, and from 1900 to the present on the east. To enhance the Tate display, a number of important loans have been included, not only paintings and works on paper, but also media which do not form part of Tate’s own collecting remit, such as coins, medals and portrait miniatures. This is particularly true for the period of most interest to readers of Renaissance Journal. Proceeding from the new entrance hall up the grand staircase, the visitor arrives in Room 1, an introductory gallery on the theme ‘Reforming British Art’. This room examines the iconoclasm—primarily that of the early-to-mid sixteenth century—which defaced or destroyed so much of the religious art of the previous centuries. A fragment of a medieval painted and gilded rood screen from Binham Priory in Norfolk, dismantled and largely destroyed at the Reformation, is a powerful visual document of the process of iconoclasm. This surviving panel was whitewashed over and painted with texts from Thomas Cranmer’s English translation of the Bible (published 1539). The lettering has now partly worn away to reveal a painted and gilded image of Christ as the Man of Sorrows beneath. From St Cuthbert’s church in Wells come a group of fragments of fifteenth-century carved and painted stone figures, many of which originally formed part of a Tree of Jesse. Battered and broken, with some traces of remaining paint, they demonstrate the richness of the visual culture displaced by the Reformation, and the violence and determination of the attacks upon it. Room 2 bears the title ‘English Renaissance’ and covers the sixteenth and early seventeenth century in Britain. It contains some of the most celebrated pre-twentieth-century works in the Tate collection, such as Marcus Gheeraerts II’s full-length Portrait of Captain Thomas Lee of 1594, the anonymous religious image An Allegory of Man of the late 1590s and, of course, the Cholmondeley Ladies, 1600-10, which represents regional portraiture—possibly, in this case, produced by a Chester artist—in a visual presentation fashionable in court circles at least twenty years earlier. The display begins with a carved alabaster panel of The Trinity, dating from the second half of the fifteenth century, lent by the Victoria and Albert Museum. Religious works in this medium were once numerous and appear regularly in contemporary inventories. The Trinity is contrasted with a rare English terracotta bust of Sir Gilbert Talbot of Grafton, c.1511-17, again lent by the V & A, and thought to come from the studio of Pietro Torrigiano, the Italian sculptor who came to London to produce the monument to Henry VII and his queen (1512-18) in Westminster Abbey. Most of the earliest surviving English portraits on panel are of royal subjects. Few turn out to be contemporary with the sitters, and many are slightly later copies. The small portrait of Henry VII lent by the Society of Antiquaries is, however, thought to date from c.1500. In it, the king wears a jewelled collar emblematic of his status, and grasps a Lancastrian red rose. It is wholly different in scale and ambition from Hans Holbein II’s portrait of Sir Henry Guildford, lent by her Majesty the Queen. This was painted in 1527, soon after Holbein’s initial arrival in England and the year in which Guildford, as Comptroller of the Household, oversaw the celebrations of peace with France, for which Holbein was employed on the decorations. Holbein’s English career is also represented by the Lady with a Squirrel and a Starling, 1526-8, generously lent by the National Gallery. Although Holbein’s influence can be seen in John Bettes’s portrait of an Unknown Man (1545), there was, after Holbein’s death in 1543, an apparent retreat from a desire for naturalism in portraiture. This display illustrates this trajectory, with Tate works such as the anonymous portrait of A Young Lady aged 21, 1569, George Gower’s Sir Thomas Kytson of 1573, and the ‘Phoenix’ portrait of Elizabeth I, c.1575, attributed to the miniaturist Nicholas Hilliard. Hilliard’s work as a portrait miniaturist— his primary arena—is seen in a separate display, along with that of his pupil and subsequent rival Isaac Oliver, in a near-adjoining gallery (Room 5) dedicated to the Portrait Miniature. This presents a full spectrum of portraits on a small scale, beginning with Holbein’s image of Mrs Jane Small (c.1540), almost all lent by the V & A. Room 2 emphasises the international nature of sixteenth-century English visual culture with the Antwerp-trained exile Hans Eworth’s painting of A Turk on Horseback, 1549 (private collection) probably intended to represent Suleyman the Magnificent. Also on display in this room is a hand-coloured copy of volume III of Georg Braun and Frans Hogenberg’s printed assembly of urban views and maps of the world, Civitates Orbis Terrarum, which was created from within a Protestant, humanist network of exiles from the Spanish Netherlands, many of whom spent time in England. A group of medals on loan from the British Museum begins in 1480 with a bronze representation of the Englishman John Kendal, fashioned in Italy. Four fine silver medals made in England in 1562 by the Netherlander Steven van Herwijk demonstrate the Elizabethan market for such skills. A silver medal of the Queen herself, of c.1574, bears a phoenix on the verso—a personal emblem of Elizabeth’s, also seen upon the pendant in Hilliard’s portrait of her on the adjoining wall. Hilliard’s work as a medallist for Elizabeth’s successor is also represented, by the 1604 silver James I: Peace with Spain. The richness of the visual culture of the period reached its apogee in the last years of Elizabeth’s reign and the first years of James I’s, exemplified here in the Tate’s elaborate full-length allegorical portrait of a lady dated 1615, splendidly dressed, standing in the open air beside a fruiting peach tree and raising her mantle to shield her person from the sun. Both the name of the artist and her identity are now unknown—the traditional name ‘Elizabeth Tanfield’ is possible, but unproven. With the end of the second decade of the seventeenth century came a new wave of Netherlands-trained painters introducing a more observed naturalism, and working for the most elite members of court. These are represented by Cornelius Johnson’s Susanna Temple, later Lady Lister, 1620, a head-and-shoulders in the now-fashionable feigned oval format, and Daniel Mytens’s dramatic full-length of James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, later 3rd Marquis and 1st Duke of Hamilton, signed and dated 1623. Collections 2002-1500 will remain on view with minor modifications until late 2002 when, as part of the Tate programme of refreshing its displays, a further group of works will be hung, to present other angles on the story of British visual art.