Documented Essay

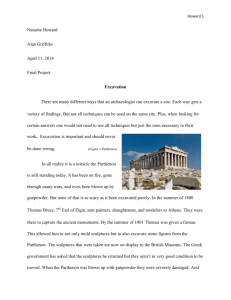

advertisement

Therese Hanshaw Humanities2211 Ms. Karen Frank April 14, 2007 Parthenon vs. Colosseum Two ancient structures, the Greek Parthenon and Roman Colosseum, symbolized changing views in the civilizations in which they were built. It was evident by the architecture of each building that these attitudes opposed one another. Each used different mediums, and their shapes varied greatly. The compositions diverged as well, as one was built in opulent decoration while the other maintained a more conservative style. To begin, each structure’s intended function determined the building materials. The Athenian leader Pericles inspired the Parthenon construction in the early 440’s B.C. He intended it to represent Athens’ power and glory after its defeat of Persia. He selected Phidias, who is considered the greatest sculptor of ancient times, to supervise the project, and Phidias, in turn, delegated the construction to architects Ictinus and Callicratres (Nardo, Parthenon of Ancient Greece 32). The builders decided to use Pentelic marble for most of the building, since the marble was of high quality and available nearby. In the uppermost section, iron beams enclosed in marble helped brace heavy statues (Bruno 196). Other materials included bronze, ivory and gold, especially in the statues found inside. In contrast, the Colosseum was constructed in a conservative style. In A.D. 72, Emperor Vespasian decided to build a stone amphitheater as a statement against the former ruler, Nero (Nardo, Roman Colosseum 30). Nero had been “flamboyant and flashy” (Nardo, Roman Colosseum 29). Vespasian wanted a structure that embodied the complete opposite, more in keeping with the basic Roman style. The amphitheater consisted mostly of concrete, stone, and wood. The foundation was made from volcanic ash mixed with lime, which was then added to coarse sand and gravel (Nardo, Roman Colosseum 38). Underground chambers above the foundation were covered with a wooden floor, carpeted in sand (Hopkins and Beard 134). Accordingly, each structure’s shape was different. The Parthenon contained various shapes within its rectangular silhouette, including alternating rectangles along its Doric frieze, while a triangular cover completed the design. Inside was a main central room called a cella, and an opisthodome or rear chamber. Each end had eight columns and each side consisted of seventeen. This was more than the usual six-by-thirteen arrangement but still followed the two-to-one ratio common at the time. Conversely, the Roman Colosseum was oval-shaped, adding to the design of the Theater of Marcellus, after which it was modeled (Nardo, Roman Colosseum 31). The Colosseum employed many arches and barrel vaults to support ascending seats (Nardo, Roman Colosseum 33). The oval bowl measured 620 by 513 feet wide and over 156 feet high (Nardo, Roman Colosseum 51). Finally, the composition of the Greek Parthenon and the Roman Colosseum varied greatly. The Parthenon was constructed on an existing platform from an older unfinished Parthenon, but the new one measured more than 24 feet wider and over eight feet longer (Bruno 172). The Parthenon modeled the basic Doric Style, marked by certain column shapes and decorative features. The Parthenon employed fluted columns laid directly on the temple floor. The columns consisted of drums, or rounded stones, stacked tightly on top of one another. Later, Doric capitals topped the columns, which made each column’s height about five and a half times its diameter, typical of this style. Above the capitals was the entablature, which included the epistyle, a beam that supported the upper sections of the structure. Also part of the entablature was the Doric frieze, a sculpted band that ran horizontally, broken up by alternating triglyphs and metopes. The triglyphs, rectangular blocks of three vertical bars, were placed directly above each column and again above each junction of epistyle blocks, establishing fourteen metopes on each end and thirty two on each side, another mark of the Doric style (Nardo, Parthenon of Ancient Greece 45). Sculptures in relief adorned the metopes. The sculptures represented scenes of Athens’ triumph over various enemies, such as the Olympian gods, the Amazons and the Trojans. Over the entablature was the final section, the cornice, which also consisted of several parts. The bottom piece was called the geison. This stone beam lay on the Doric frieze, and on the underside were rectangular decorations called mutules (Nardo, Parthenon of Ancient Greece 48). On the ends of the Parthenon, the cornice had the raking sima. The raking sima constituted the sections forming the pediment, which housed sculpted figures. These figures sometimes carried bronze swords, and many were painted bright colors. They often represented myths of Athena. The last piece of the Parthenon was the Ionic frieze, which ran behind and parallel to the Doric frieze. It was a continuous band of sculpted reliefs. Contrary to the Parthenon, the Colosseum was built on a concrete foundation that originated as Nero’s drained lake. Since the amphitheater was freestanding with underground corridors and chambers, the weight had to be born mostly by the walls. An inner ring of concrete twenty feet thick spread outward from the foundation to support the outer walls (Nardo, Roman Colosseum 38). These walls were made up of limestone pillars, arches, and vaults. All together the Colosseum held four levels, mostly filled with seating and exits leading out to barrel- vaulted corridors. These, in turn, intersected with longer curving corridors and stairways. There were eighty entrances to the Colosseum (Hopkins and Beard 128). Except for the three styles of columns found between the arches, the outer façade was fairly plain supporting the conservative style in which the structure was intended. The Colosseum’s bottom level applied Doric half-columns, the second level contained Ionic, and the third incorporated Corinthian. The fourth level had no arches. Instead, it featured rectangular half-columns with Corinthian capitals. Originally, the Colosseum had a velarium, or canopy made of canvas strips to cover the open ceiling. Along with the seating, this feature no longer exists. To conclude, the Greek Parthenon was constructed to honor a powerful city-state as well as the goddess Athena. The structure represented this power through the use of the finest materials, a grand shape and detailed composition. However, the Colosseum was erected at a time when Rome hoped to rebound from a lavish and wasteful ruler, Nero. To epitomize this new conservative mood, the Colosseum employed basic materials, an oval shape and undecorated arrangement. Both edifices, though very different, were realized through hard work and dedication. Works Cited Bruno, Vincent J., ed. The Parthenon. New York: Norton, 1974. Hopkins, Keith, and Mary Beard. The Colosseum. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2005. Nardo, Don. The Parthenon of Ancient Greece. San Diego: Lucent, 1999. ---. The Roman Colosseum. San Diego: Lucent, 1998. Word Count: 988