Hoplistoscelis heidemanni

advertisement

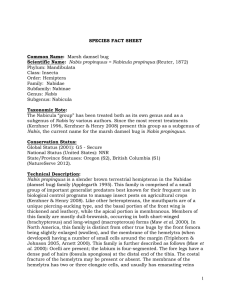

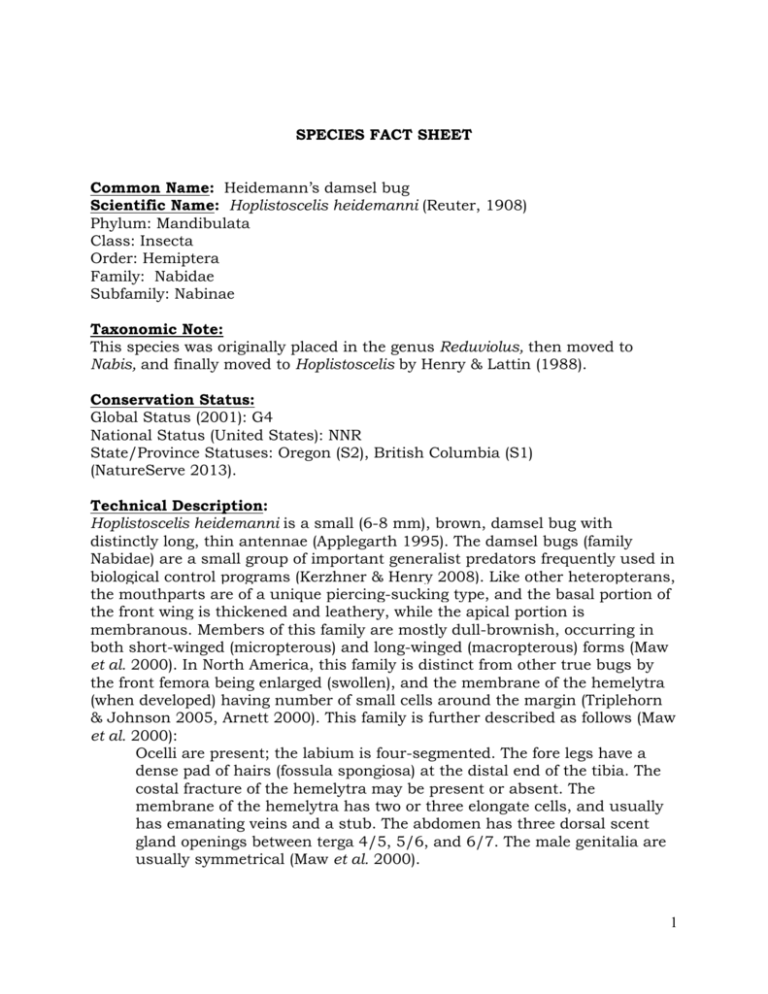

SPECIES FACT SHEET Common Name: Heidemann’s damsel bug Scientific Name: Hoplistoscelis heidemanni (Reuter, 1908) Phylum: Mandibulata Class: Insecta Order: Hemiptera Family: Nabidae Subfamily: Nabinae Taxonomic Note: This species was originally placed in the genus Reduviolus, then moved to Nabis, and finally moved to Hoplistoscelis by Henry & Lattin (1988). Conservation Status: Global Status (2001): G4 National Status (United States): NNR State/Province Statuses: Oregon (S2), British Columbia (S1) (NatureServe 2013). Technical Description: Hoplistoscelis heidemanni is a small (6-8 mm), brown, damsel bug with distinctly long, thin antennae (Applegarth 1995). The damsel bugs (family Nabidae) are a small group of important generalist predators frequently used in biological control programs (Kerzhner & Henry 2008). Like other heteropterans, the mouthparts are of a unique piercing-sucking type, and the basal portion of the front wing is thickened and leathery, while the apical portion is membranous. Members of this family are mostly dull-brownish, occurring in both short-winged (micropterous) and long-winged (macropterous) forms (Maw et al. 2000). In North America, this family is distinct from other true bugs by the front femora being enlarged (swollen), and the membrane of the hemelytra (when developed) having number of small cells around the margin (Triplehorn & Johnson 2005, Arnett 2000). This family is further described as follows (Maw et al. 2000): Ocelli are present; the labium is four-segmented. The fore legs have a dense pad of hairs (fossula spongiosa) at the distal end of the tibia. The costal fracture of the hemelytra may be present or absent. The membrane of the hemelytra has two or three elongate cells, and usually has emanating veins and a stub. The abdomen has three dorsal scent gland openings between terga 4/5, 5/6, and 6/7. The male genitalia are usually symmetrical (Maw et al. 2000). 1 The Nabidae family contains two subfamilies, 11 genera, and 39 species in North American (Kerzhner & Henry 2008, Henry 2009). The Hoplistoscelis genus belongs to the Nabinae subfamily. The following characters distinguish the Hoplistoscelis genus from other closely related genera in the subfamily: head behind the eyes parallel-sided or nearly so (as opposed to obliquely narrowed behind the eyes); body mostly grey or brownish in color (as opposed to shiny black with yellow appendages) (Harris 1928). Adults of this genus are usually wingless or have small rounded pads instead of functional wings. They are about 6-8 mm long, and their bodies are generally wider than the other damsel bug genera (Slater & Baranowski 1978, Elvin & Sloderback 1984, Applegarth 1995). A total of five species of Hoplistoscelis occur in North America north of Mexico: H. confusa, H. heidemanni, H. hubbelli, H. pallescens, and H. sericans (Kerzhner & Henry 2008). With the exception of H. confusa in the southwestern United States (e.g., Arizona, where both species have been documented), none of these species are known to overlap with H. heidemanni in range. In Oregon and Washington, Hoplistoscelis heidemanni is the only member of this genus known to occur. Morphologically, Hoplistoscelis heidmanni is distinguished from other members of the genus by the following characters: front and mid femora armed beneath with minute short, rather blunt, blackish teeth (as opposed to unarmed or with minute spine like setae, never short teeth); tibiae annulate throughout their entire length (as opposed to not annulate, or if so, only at the base and apex) (Harris 1928). A full description of the species is as follows (Harris 1928): Oblong or oblong-ovate, fuscous to fusco-testaceous, opaque, pubescent, also thickly pilose. Head about as broad as long, with two posteriorly converging fuscous lines above. Eyes large, the length of one equal to width of vertex. Ocelli placed closer to eyes than to each other. Antennae long, testaceous, segment I at base and II before the apex with fuscous rings; segment I equal to width of head through eyes. Rostrom with segments II and III subequal, each slightly longer than antennal segment I. Pronotum with a distinct median longitudinal line and more or less distinct pattern on anterior lobe, and five obscure lines on posterior lobe fuscous. Scutellum with a calloused white spot on each side. Hemelytra with moderately long, semierect pubescence, somewhat irregularly spotted with brownish fuscous, the veins lighter and often tending toward crimson. Legs clothed with prominent erect or semierect hairs, fusco-maculate, the tibiae distinctly annulate. Front and mid femora armed beneath with distinct short grain-like teeth, the former about 3.5 times as long as thick. Hind tibia with its longer hairs about twice as long as the diameter of the tibia and standing out almost perpendicularly. Abdomen above densely clothed with prostrate, silvery, downy pubescence; with a distinct naked patch at the base of each 2 tergite in the median line, also each tergite on either side with a transverse naked patch. Connexivum testaceous sometimes obscurely marked with crimson, the segments each with a basal fuscous patch. Venter with a broad stripe on each side and a narrow median one fuscous, each segment with a conscious naked patch on either side next to the connexivum. Male narrow, rather elongate, the clasper slender with a long blade. Brachypterous form: pronotum as broad as long, the anterior lobe rather strongly arched. Hemelytra extending onto the base of third dorsal segment, broadly rounded or almost truncate at apex; membrane very small, without veins. Length 7.2-8.7 mm, width 1.561.92 mm (at abdomen, 2.7-3.6 mm). Macropterous form (female): pronotum distinctly broader than long. Scutellum much larger than in brachyperous form. Hemelytra extending scarcely to tip of abdomen, obliquely narrowed from a point opposite middle of commissure; membrane with veins fuscous, broad and prominent. Length 8.88 mm; width 2.28 mm (at abdomen 3.5 mm). Harris (1928) describes this as a distinct, easily recognizable species. See Attachment 4 in the Appendix for a photograph of the brachypterous adult female. A photograph of the macropterous adult is available on BugGuide.net (http://bugguide.net/node/view/296746#631950, accessed March 2013). Immature: Immature nabids have a long, slender, 4 segmented labium arising from the anterior part of the head (Elvin & Sloderback 1984). They also have long, slender antennae, apical tarsal claws, and usually 3-4 pairs of scent glands present on the abdomen. The labium is not located in a rostral groove in the gular region (Elvin & Sloderback 1984). The nymphal instar of a particular immature nabid can be determined by assessing the amount of wing pad development (see Elvin & Sloderback 1984 for details). Some immatures of Hoplistoscelis show little or no wing pad development; however, they can be distinguished from immatures of the other genera by their distinctive body shape (pear-shaped as opposed to elongate-oval) (Elvin & Sloderback 1984). There are no keys available for identifying the nymphs to species, but note that H. heidemanni is the only member of this genus known to occur in the Pacific Northwest. See Attachment 4 in the Appendix for an illustration of a representative nymph of this genus. Life History: Nabid bugs are aggressive generalist predators, feeding on wide variety of small arthropods including caterpillars, aphids, and plant bugs (Marshall 2006, Triplehorn & Johnson 2005). Nabid nymphs are active shortly after hatching and begin feeding immediately, often on prey considerably larger than themselves (Lattin 1989). 3 The phenology of this species is poorly known. According to Applegarth (1995), specimens have been found [presumably in Oregon] in early spring and late summer, although both of the recently recovered Oregon specimens were collected in August (OSAC 2013). This species has been collected in June & October in California (BugGuide 2013, OSAC 2013), July and October in Idaho, and July in Arizona (OSAC 2013). Nabids tend to overwinter as adults (Applegarth 1995, Lattin 1989). Adults of Hoplistoscelis sericans have been found overwintering in harvested corn fields in Florida; in this study, 10 adults were found between the layered husks around shelled cobs, and two adults were collected under the corn leaf sheath (Plagens & Whitcomb 1986). Dispersal behavior in H. heidmanni has not been examined. The macropterous (fully-winged, flight capable) form of some adult nabids are known to move considerable distances (Lattin 1989), probably in response to instable habitats or food sources. Many aspects of this species biology are unknown, including dietary preferences, mating behavior, oviposition site selection, number of eggs laid, development time, life span, number of generations per year, dispersal behavior, and overwintering behavior and habitat. Range, Distribution, and Abundance: This species is known only from Western North America. In Canada, it is documented from British Columbia (Anarchist Mountain and Haynes Ecological Reserve-Osoyoos) (Scudder 1996, Maw et al. 2000). In the United States, it is documented from Idaho (Latah County), California (Monterey County), Oregon, Arizona (Yavapai County), and Utah (Henry & Lattin 1988, Applegarth 1995, OSAC 2013, USNM 2013, Kerzhner & Henry 2008). In Oregon, known records are from Benton County (Corvallis) and Curry County (Humbug Mountain) (Applegarth 1995, OSAC 2013). BLM/Forest Service lands: This species is Suspected on Siuslaw National Forest and BLM land in the Coos Bay District, based on proximity to a known record. The Eugene and Salem BLM Districts also suspect the species. Abundance: Abundance estimates of this species have not been conducted. Known collections in Oregon are both of single individuals (OSAC 2013). Habitat Associations: Applegarth (1995) describes the habitat for Hoplistoscelis heidemanni as forest riparian areas and skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus) swales. The habitat at the Humbug Mountain site was described as a stream bank (Applegarth 4 1995). The habitat at the Corvallis site is unknown. In Idaho, this species has been collected from “yellow pine”, and in Arizona, from Ceanothus, a genus of shrubs in the family Rhamnaceae (OSAC 2013). In Eastern North America, the related H. sericans has been found under bark of a dead tree (BugGuide 2013). The related H. pallescens has been found visiting flowers, under leaf litter in a flower bed, on the top surface of leaves, and preying on adult flies (BugGuide 2013). Both H. pallescens and H. sericans have been found at lights (BugGuide 2013). Threats: Threats to this species have not been evaluated. Habitat loss or alterations are probably primary threats, but specific issues are difficult to assess given the limited information on this species’ distribution and habitat requirements in Oregon. Conservation Considerations: Inventory: This species is known from very few collections in Oregon, perhaps due to limited sampling effort. Further surveys are needed for this species in Oregon, and will be critical in evaluating its current status and habitat use in the region. Initial surveys are recommended on BLM and Forest Service land in the vicinity of the known Humbug Mountain site where this species was last collected 1965. In British Columbia, this species is also considered a priority for inventory and descriptive research, due to being very rare or endangered at both the provincial and national levels (Scudder 1996). Management: Protect all known and potential sites from practices that would adversely affect this species or its habitat. Research: Many aspects of this species’ biology are in need of study including food preferences, mating behavior, oviposition site selection, number of eggs laid, development time, life span, number of generations per year, and overwintering behavior. Prepared by: Sarah Foltz Jordan, Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation Date: 8 April 2013 Edited by: Sarina Jepsen, Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation Date: 10 April 2013 Final edits by: Rob Huff, Conservation Planning Coordinator, FS/BLM Date: 22 April 2013 5 ATTACHMENTS: (1) References (2) List of pertinent or knowledgeable contacts (3) Maps of known records in Oregon (4) Photograph of this species & illustration of relative (5) Survey protocol for this species ATTACHMENT 1: References. Applegarth, J.S. 1995. Invertebrates of special status or special concern in the Eugene district. U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management. 126 pp. Arnett, R.H., Jr. 2000. American Insects, A Handbook of the Insects of America North of Mexico, 2nd edition, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL. 1003 pp. BugGuide 2013. “Hoplistoscelis heidemanni.” Available at: http://bugguide.net/node/view/296746/bgimage (Accessed 11 March 2013). Elvin, M.K. and P.E. Sloderbeck 1984. A key to the nymphs of selected species of Nabidae (Hemiptera) in the southeastern USA. Fla. Entomol. 67: 269-273. Harris, H.M. 1928. A monographic study of the Hemipterous family Nabidae as it occurs in North America. Entomologica Americana 9: 1-97. Henry, T.J. 2009. Biodiversity of Heteroptera. Chapter 10. Pp. 223–263 In: Foottit, R.G.; Adler, P.H. (eds) 2009: Insect Biodiversity: Science and Society. Wiley-Backwell, Oxford, U.K. 656 pp. Henry, T.J. and J. Brambila. 2003. First report of the neotropical damsel bug Alloeorhynchus trimacula (Stein) in the United States, with new records for two other nabid species in Florida (Heteroptera: Nabidae: Prostemmatinae). Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 105: 801-808. Henry, T.J. and J.D. Lattin. 1988. Family Nabidae Costa. 1853. The damsel bugs, pp. 508-520. In Henry. T. J. and R. C. Froeschner. eds. Catalog of the Heteroptera, or true bugs, of Canada and the continental United States. E.J. Brill, Leiden and New York. 958 pp. Kerzhner, I.M. & T.J. Henry. 2008. Three new species, notes and new records of poorly known species, and an updated checklist for the North American Nabidae. Proceedings of the Entomological Society of Washington 110(4): 988– 1011. Lattin, J.D. 1989. Bionomics of Nabidae. Annual Review of Entomology 34: 383–400. 6 Maw, H.E.L., Foottit, R.G., Hamilton, K.G.A. and G.G.F. Scudder. 2000. Checklist of the Hemiptera of Canada and Alaska. NRC Research Press. Ottawa, Ontario. 220 pp. NatureServe. 2013. “Hoplistoscelis heidemanni.” NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Feb. 2009. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Data last updated: October 2012. Available at: www.natureserve.org/explorer (Accessed 11 March 2013). Oregon State University Arthropod Collection (OSAC). 2013. Specimen data gathered by Ashley Clayton, contractor for the Xerces Society. Plagens, M.J. and W.H. Whitcomb. 1986. Corn residue as an overwintering site for spiders and predaceous insects in Florida. The Florida Entomologist 69(4): 665-671. Reuter, O.M. 1908. Bemerkungen über Nabiden nebst Beschreibung neuer Arten. Mém. Soc. Entomol. Belg. Vol. 15 pp. 87-130. Scudder, G.G.E. 1994. An annotated systematic list of the potentially rare and endangered freshwater and terrestrial invertebrates in British Columbia. Entomological Society of British Columbia, Occasional Paper 2: 1-92. Scudder, G.G.E. 1996. Terrestrial and freshwater invertebrates of British Columbia: priorities for inventory and descriptive research. Res. Br., B.C. Min. For., and Wildl. Br., B.C. Min. Environ., Lands and Parks. Victoria, B.C. Work. Pap. 09/1996. Triplehorn, C. and N. Johnson. 2005. Introduction to the Study of Insects. Thomson Brooks/Cole, Belmont, CA. 864pp. United States National Museum (USNM). 2013. Statement by Thomas Henry regarding USNM collection holdings of Hoplistoscelis heidemanni. Available at: http://bugguide.net/node/view/296746/bgimage (Accessed 11 March 2013). ATTACHMENT 2: List of pertinent or knowledgeable contacts Thomas Henry, Research Entomologist, Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington DC. John D. Lattin, Professor Emeritus, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon. Michael Schwartz, Research Affiliate, Insect Biosystematics, Canadian National Collection of Insects. 7 ATTACHMENT 3: Maps of known records in Oregon Known records of Hoplistoscelis heidemanni in Oregon, relative to BLM and Forest Service lands. 8 Known record of Hoplistoscelis heidemanni at Humbug Mountain, relative to BLM and Forest Service lands. 9 ATTACHMENT 4: Photograph of this species & illustration of relative Hoplistoscelis heidemanni brachypterous (short-winged) adult female, as indicated by the fully developed ovipositor (not apparent in photo) (Marshall 2013, pers. comm.). Photograph by Ashley Clayton for The Xerces Society, used with permission. A photograph of the macropterous adult is available on BugGuide.net (http://bugguide.net/node/view/296746#631950, accessed March 2013). 10 First through fourth nymphal instars of the related Hoplistocelis sericans. Illustration from Elvin & Sloderbeck (1984). Note the wide (pear-shaped) body. ATTACHMENT 5: Survey Protocol for this species Survey Protocol: Hoplistoscelis heidemanni Where: This species is known from very few collections in Oregon, probably due (at least in part) to limited sampling effort. Further surveys are needed for this species in Oregon, and will be critical in evaluating its current status and habitat use in the region. Initial surveys are recommended on BLM and Forest Service land in the vicinity of the known Humbug Mountain site where this species was last collected 1965. Oregon surveys for this species should target forest riparian areas and skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanus) swales (Applegarth 1995). The habitat at the Humbug Mountain site was described as a stream bank (Applegarth 1995). The habitat at the Corvallis site is unknown. In Idaho, this species has been collected from “yellow pine”, and in Arizona, from Ceanothus, a genus of shrubs in the family Rhamnaceae (OSAC 2013). 11 In Eastern North America, the related H. sericans has been found under bark of a dead tree (BugGuide 2013). The related H. pallescens has been found visiting flowers, under leaf litter in a flower bed, on the top surface of leaves, and preying on adult flies (BugGuide 2013). Both H. pallescens and H. sericans have been found at lights (BugGuide 2013). When: Surveys for this species are recommended in summer, although the phenology of this species is poorly known. According to Applegarth (1995), specimens have been found in early spring and late summer, although both of the recently recovered Oregon specimens were collected in August (OSAC 2013). This species has been collected in June and October in California (BugGuide 2013, OSAC 2013), July and October in Idaho, and July in Arizona (OSAC 2013). Nabids tend to overwinter as adults (Applegarth 1995). How: Since this species is known from very few collections in a variety of habitats, survey methodologies are difficult to develop. Visual searches and sweepnetting in known habitat (forest riparian areas and skunk cabbage swales) are probably the most appropriate survey method to employ at this time. It is unclear if this species has been collected from skunk cabbage, or simply in skunk cabbage habitat, but in case of the former, visual searches should target skunk cabbage leaves, including leaf surfaces and spaces between the leaf sheaths. Surveyors may also wish to target yellow pine (or other Pinus species) and Ceanothus shrubs, since H. heidemanni has been collected from these plants outside of Oregon (OSAC 2013). Given the scarcity of habitat information for this species, surveyors may also wish to target microhabitats where other members of this genus have been collected, including leaf surfaces, leaf sheaths, flowers, leaf litter and under bark (OSAC 2013, BugGuide 2013, Plagens & Whitcomb 1986). Both H. pallescens and H. sericans are known to come to visible light (e.g., porch lights) (BugGuide 2013). It is unclear if Hoplistoscelis species are attracted to ultraviolet (UV) light, but Blinn (1995) reports the use of UV light traps to collect another member of this family (Phorticus collaris). After capture, voucher specimens should be placed immediately into a kill jar until they can be pinned. A field catch can also be temporarily or permanently stored in 75% ethyl alcohol but the alcohol will cause some colors to fade (Triplehorn & Johnson 2005). Adult specimens should be pinned through the scutellum (Triplehorn & Johnson 2005). Juveniles are best preserved in vials containing 75% ethyl alcohol. Collection labels should include the following information: date, collector, detailed locality (including geographical coordinates, mileage from named location, elevation, etc.), and detailed habitat/host plant. Complete determination labels include the species name, sex (if known), determiner name, and date determined. 12 Field identification is possible by those familiar with heteropteran taxonomy, and can be accomplished by non-experts who have examined and become familiar with museum specimens. This species is identified using characteristics provided in the Species Fact Sheet. Confirmation of field identifications should be done by taxonomic experts with experience identifying nabids. 13