Asa proof of Latin America`s intentions, the first combined

advertisement

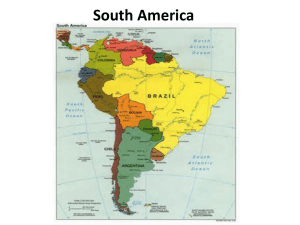

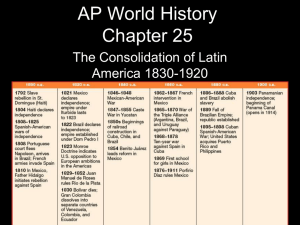

Latin America-Africa Cooperation: Brazil as a Case Study Gladys Lechini 1 Historically, relations between Latin America and Africa have gone through periods of rapprochement and also through mute stages. These ups and downs were and still are closely related to domestic situations and to international and regional ones. These relations come from the XVI Century, with the slave trade. During this shameful period, Latin America and the Caribbean received the Africans, together with their culture and their values, which became part of the heritage and the profile of the different nations in the region. Since the Latin American countries’ independence, during the XIX Century, the two regions were connected through the European countries, and their relations had a very low profile. This situation began to change in the XX century, this time, with the independence of African states. Their inclusion in the post second world war international system had a strong impact in multilateral regimes and in UN, where the Latin American states backed up the incorporation of the new African partners, beginning a new type of relationship. During the 60’s and seventies, the countries of the “Third World” participated actively in international fora, to defend their interests through concerted actions: G 77, the Non Aligned Movement and the UN General Assembly were the privileged meeting places. Nevertheless, during the 80’s a new period of silence covered the relations. The bilateral synergy was weakened by the serious problems concerning the external debt which affected development and democratic stability in the South. 1 Professor of International Relations at the National University of Rosario. Researcher at the National Council for Scientific and Technological Research, Argentina (CONICET) Academic Advisor CLACSO’s South-South Program. Director Institute for South-South Relations (IRESS) 1 In the 1990s, the end of the Cold War brought the end of bipolarity and diminished the alternatives for Latin America and Africa to solve their problems and improve their international insertion. Furthermore, the expansion of globalisation, the implementation of neoliberal policies, and the severe economic problems faced by developing countries dissolved any solidarity. South-South cooperation was not in the priorities of the foreign policy agendas of the countries in both regions. Neither it was included in the speeches of leaders, nor it was at the decision making level or in academic analysis. The effects of globalisation made it clear that there were new winners and losers, but also that very few winners belonged to Southern countries. This awareness, along with the disappointment regarding the possibility that a new global system based on the socalled IFIs (International Financial Institutions) and the WTO (World Trade Organisation) might contribute to establishing a fairer international order, led the governments of the Global South to rethink the idea of horizontal cooperation, but this time adopting a more selective approach in terms of players and issues, and learning from past experiences. “South-South Cooperation” shows that it is possible to create cooperative awareness from the South, which may enable countries to jointly tackle their common dilemmas in the international arena. In front of situations seen as unfair, cooperation among peers, among those enduring the same dependency situations, would help them underpin their negotiating capacity vis-à-vis the North, through cooperative efforts aimed at solving issues on trade, development, and the new international economic order. Africa and Latin America: between similarities and diversities Before dealing with the cases under study, I will briefly comment on some similarities between the two regions as well as on some characteristic of the horizontal relation. 2 Despite the mutual lack of knowledge of the other and the absence of communications for various periods, it is interesting to note that the two regions have remarkable similarities. Both have suffered from colonialism, both have fought strongly for their independence, both have dependent and asymmetric relations with the industrialized countries (the North) and dependent economic structures, both have undergone the economic hardships caused by SAPs albeit at different time frames. What makes the difference is the fact that democracy has been recovered almost twenty five years ago in Latin America, though in Africa many countries are still struggling with restoring democratic governance. Connected to this it can be pointed that the Latin American region can show in this new Century elected governments with inclinations to the left in what has been called “the new populism”. The pattern of relations between Latin American and African states shows that Latin American countries had been main initiators. However, South Africa has reacted to this pattern by approaching Latin American countries, in different periods, with the same object: to improve its international insertion through the diversification of political, economic and strategic relations. On the other hand, Africa’s relationship with Latin America has been characterized by various models that reflect the continent’s diversity. These models have included the Cuban Model, Brazilian Model, Argentinean Model, and Venezuelan Model. This change in the norms elicited various responses. Argentina accommodated to South Africa’s approach. Brazil, in contrast, preferred interacting with different countries. Cuba’s approach privileged the ideological dimension and technical cooperation. Venezuela, the new player, is learning how to move towards Africa within de various aspects of South-South cooperation 3 Argentina and South Africa An analysis of the evolution of Argentine-African relationships since the independence of these states reveals that Sub-Saharan Africa holds a low profile in Argentine foreign priorities, given the scarce links established and the lack of continuity by the successive Argentine governments. A combination of typical factors related to Argentina’s political instability, to its ensuing foreign policy stance, along with changes in the international scenario and the special situation of African countries have conditioned Argentina’s weak and erratic ties with those countries. Argentina’s foreign policy vis-à-vis the African states in general and South Africa in particular may be described as an impulse-driven policy, which have varied in intensity with the years, governments, and projects of international insertion2. The impulses are external and usually discontinuous actions which have accounted for the rapprochement with the African states for brief periods. These actions have set up a pattern of relations which, regardless of its ups and downs, may be defined as erratic and jerky. The impulses may in fact be measured through a set of indicators such as opening embassies, sending and receiving diplomatic or trade missions, signing agreements, through the sudden changes in the balance of trade with a given country, and so forth. It should be noted that foreign policy may be driven by impulses, i.e., by external actions directed to another international player, in this case a state, which occur throughout time. It is the continuity and contiguity of these impulses what would define it as a policy based on a design approach. The accumulation of impulses in a given context would entitle to speak of policy building. Otherwise, a set of isolated impulses 2 The opinions expressed in this paper are the outcome of my research at CONICET and have been discussed in greater depth in Lechini, Gladys “Argentina y África en el espejo de Brasil. ¿Política por impulsos o construcción de una política exterior” CLACSO, Buenos Aires, 2006. 4 usually bears no effects or consequences and gets lost in the thematic schizophrenia of our foreign offices. This jerky impulse-driven policy also shows a particular decision-making process. Owing to the low priority held by African states in the policies implemented by both civilian and military Argentine governments, the decisions made by impulse were regarded as “routine” procedure at Palacio San Martin (Ministry of Foreign Affairs). Moreover, many of the bilateral or multilateral initiatives (within the frame of the NonAligned countries or the UN) often relied on the good will and imagination of the argentine officials, who managed to have leeway in advancing actions or missions within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ monolithic and hierarchical structure. Hence, the different bureaucratic bodies (“the Departments”) did not usually take a concerted action due to the lack of strategies or policies crafted on the basis of rational criteria and long term opportunities. Within this scenario, and because African states were not among Argentina’s external priorities, the gaps created in the marginal leeway available served to channel good ideas. However, these were isolated efforts because of the Ministry officials’ turnover hindering the follow-up and continuity of “low-profile” actions and because of the political and economic instability of the potential partners across the Atlantic. The above mentioned impulse could advance in the decision-making process thanks to the insistence of officials at different levels and could made its way up the decision-making pyramid insofar as the action should not be “costly” in political or economic terms. Within this rationale framework, numerous valuable reports and recommendations made by officials accredited to African states or Buenos Aires were lost in the intricacies of Palacio San Martín. It might therefore be concluded that these impulses reflect the different rapprochement 5 initiatives with African states. Their intensity depended on the content-objective and also determined their positioning in the decision-making pyramid. If the content of the impulse agreed with the government’s policy, its intensity would grow and the decision would be taken at the highest levels. If the impulse or the interest was minor, the decision would be taken at the middle tier of the bureaucratic hierarchy. The relation between the intensity of the impulse and the decision-making levels depended on where the issue in question was placed in the overall picture. Hence most decisions would fall within the dynamics of routine. The most remarkable exception was the breaking-off and resumption of diplomatic relations with South Africa, which shows that such decisions fell within the overall policy design and were therefore taken at the highest level. The aim, however, was not exclusively South Africa per se, but to reach other targets regarding issues seen as relevant in the strategies deployed at the time. An analysis of the evolution in Argentine-South African relations identifies 4 stages: a) A two-fold policy and equivocal relations from 1960-1983, when relations with the then racist South Africa were developed by mutual impulses, with military-strategic and commercial objectives3 b) A period of policy definition for a racist South Africa, with the breaking-off of diplomatic relations by Alfonsín’s government on 22nd May 1986, concurrently with a new design for the relations with the other African states. c) The resumption of diplomatic relations with South Africa on 8th August 1991, during Menem’s office, who visited the country in February 1995. This impulse is accounted for by the president’s personality and interests rather than by the existence of a policy design. Lechini, Gladys, “Las relaciones Argentina-Sudáfrica desde el Proceso hasta Menem” Ediciones CERIR, Rosario, 1995 3 6 d) This stage started in 2005 with the agreement to set up a Binational Commission, which finally materialised in February 2007 on the occasion of Foreign Secretary Jorge Taiana’s visit to South Africa4. Argentina’s diplomatic relations with South Africa show some particularities which make them different from other African states. Up to Alfonsin’s government, mutual impulses generated a certain density of relations. The breaking-off diplomatic relations provoked a watershed with the subsequent absence of political relations and impulses. But bilateral trade continued in separate avenues and was not strongly influenced. The breaking-off diplomatic relations was not an impulse as it was part of the foreign policy’s general strategy of Argentina at that time. The objective was to recover, in the international scenario, the credibility lost with the military governments and to defend the Human Rights cause. The quick re-establishment of diplomatic relations decided by Menem turned that policy into an impulse. Even though during his administration a higher density of bilateral relations took place, South Africa was not included among Argentina’s priorities. That is why the external actions were transformed into a new impulse, aiming at very specific objectives and loosing a good opportunity to build common South-South political agendas. This impulse, with its peak during Menem’s visit to South Africa in 1995, is much more connected with the way the president built his own image, under the assumption that his image was the final representation of his country, which deserved a place among the most important nations in the world. During the 90s, the pattern of relationship developed as follows: the goal of the South African rapprochement was to learn from the Argentine experience in the privatization 4 Foreign Secretary Jorge Taiana led the multisectoral trade mission to Pretoria comprising 43 Argentine companies from a range of industries (biotechnology, agricultural machinery, electric machinery, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, foods, teaching services, T&T, and auto parts). 7 process and the economic reform, and the Argentine one was to attract South African investments in mining and to increase exports selling agricultural commodities. With the coming of Fernando de la Rua to the presidency in Argentina (1999) and despite the set of proposals of the Alianza that took him to power, substantial changes were not observed either in the foreign policy or in the relations with the states of the African continent and South Africa The political and economic internal crisis that culminated with the president’s resignation obliged all government’s agencies to manage the crisis, both in its domestic dimension as well as in its international implications (Lechini, 2001). With president Eduardo Duhalde (2002-2003), certain internal stability could be attained. However, after having declared the default, the negotiation of the foreign debt centered almost all the energies of the external actions, showing a reactive and inertial foreign policy. According to Miranda (2003;69), the caretaker government’s foreign policy was largely tied down by the Argentine situation, it was a “scenario-driven” foreign policy. Notwithstanding this, Foreign Affairs Secretary Carlos Ruckauf sought to innovate and spoke of conducting a foreign policy of “polygamy with the different continents”. This odd diplomatic expression attempting to identify MERCOSUR, Europe, Asia, and Africa as the targets of the national government’s foreign policy was used, above all, to be distinguished from the “carnal relations” with the US, fostered by Menem. Since President Néstor Kirchner took office (2003), the idea of South-South cooperation may be spotted in his discourse on foreign policy. After more than a decade of foreign policy based on neoliberal principles, where the economy prevailed over politics and values, multilateral sectors have called for South-South cooperation, conceived as a space to seek new ways for promoting development and autonomy. 8 In this sense, a number of initiatives such as the South America – Arab Countries Summit (held in Brasilia in May 2005), the Africa-Latin America Summit (held in Abuja on 30th November 2006), and the relaunching of the Zone for Peace and Cooperation in the South Atlantic (ZPCSA) in Luanda, in June 2007, have been adequate international political forums to show Argentina’s intentions regarding SouthSouth issues. Likewise, with regard to multilateral trade within the WTO, Argentina followed its MERCOSUR partner, Brazil, in promoting common positions and joint negotiations among G20 and NAMA-11 countries. The discourse emphasis on South-South cooperation was also reflected in the relationships with South Africa. In fact, on the occasion of his visit during a multilateral mission in 2007, Foreign Secretary Jorge Taiana stated that “Argentina and South Africa have started to build a new strategic relationship which will surely become a South-South cooperation model” (…) “to Argentina’s foreign policy and administration, this is a very significant visit since Argentine-South African relations are a top priority for Argentina’s foreign policy and for South-South cooperation and relationships. We share the same principles and values. We share the principle of multilateralism as a way of solving problems in the international community”5. However, regarding bilateral relations, the South-South option is still focused from a commercialist/pragmatic perspective. Although Latin America’s regional economic conditions favour an increase in South-South cooperation, it seems that the President and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs are having difficulty developing policies beyond the Atlantic. The missions sent and received show a more commercial than political content, which proves there is still a lot to do in this sense, as evidenced in the “Taiana described the trade and political mission to South Africa as successful”. Press Release No 056, 28th February 2007. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, International Trade, and Worship website: http://www.mrecic.gov.ar/portal/prensa/prensa.php?buscar=02/2007 5 9 unsuccessful meeting between Kirchner and Mbeki when the latter did not visit Argentina during his Latin American tour in 2005. However, a Binational Commission began to take shape as a result of a preliminary meeting held in Pretoria in 2006 and the subsequent visit of Minister Jorge Taiana, in February 2007, to attend the first meeting of the Binational Commission. The following one is to be held in Buenos Aires in December 2008. BRAZIL’S AFRICAN POLICY Brazil’s relations with African states are different from those of Argentina’s, because Brazil constructed an African Policy in the framework of a global strategy of Brazil’s integration into the world. Although in the 60s both countries began to design strategies for the new African states, with Argentina even taking the lead, throughout the years their approaches showed different features. Brazil designed and implemented a set of political and diplomatic actions aiming at building a “critical mass” of commonalities and Argentina created a spasmodic-like relation. Though Brazil’s African Policy was characterized by Brazilian academics as a diffuse process, it turns to be coherent in comparison with Argentina’s impulses. Impulses in Brazil were “cumulative” and made possible the existence of certain density of relations between Brazil and Africa, in what can be considered an “incremental policy”. Unlike Argentina, impulses were generated at the upper levels of the decision making process. Thus, Brazil’s Foreign Policy shows much more continuities than Argentina’s, even with the changes of regimes (democratic and military regimes occurred in both countries). In this context, Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Itamaraty) was able to maintain a great level of independence, still with different governments, in comparison with Argentina. With all possible nuances, there is a certain continuity in the designs and implementation of Brazil’s Foreign Policy connected with the internal development 10 project (National development through imports substitution). As African states had a place in Brazil’s foreign design, political actions resulted in the construction of an African policy. That explains the higher density of diplomatic and, later, commercial relations. The rapprochement had a political nature -in the context of South-South relations- and a pragmatic commercial nature, due to the interest in diversifying trading partners. It was justified with principles -the development of SouthSouth solidarity- and belonged to a global strategy: to have an international presence through the diversification of external relations and the building of alliances with the new states in the South. This way Brazil would have a say in global issues. Perhaps these new relations can also be explained due to the impossibility, at that stage, to have better ones with Latin American states and particularly with Argentina, owing to the hypothesis of conflict between both countries’ military governments. Even though Brazilian officials resorted to a “cultural speech” or a “cultural diplomacy” reminding Brazil’s African heritage -it is the country with the biggest African population out of Africa- new actions were necessary in order to convince the African states of Brasilia’s intentions. Embassies were opened and high level missions were sent. Technical and academic cooperation was developed and research centers were opened. The seventies were called the “golden period” of Brazilian-African relations. The relation with South Africa showed varied edges. As in the case of Argentina, the African states always claimed for the breaking-off relations with the racist government. Nonetheless, Brazil did not need to appeal to such a drastic action to show its commitment towards African states and South Africa’s people. This could be explained by the fact that Brazil had generated such a density of relations that a shadow of a doubt was not left regarding Brazilian intentions. The evolution of Brazil’s policy towards South Africa, in the most general framework 11 of Brazilian-African relations, also showed oscillations. Nevertehless, a lower profile was being defined according to the improvement of Brazilian’s relations with African states and the deterioration of South Africa´s domestic situation. Therefore, South Africa´s domestic policy became a participant variable in the development of Brasilia’s relations with Pretoria. As in the Argentine case, the strongest impulse stemmed from South Africa with the “outward policy”, holding strategic and commercial objectives. In the bilateral relation Brasilia gave tepid answers to South African impulses -till the middle of the seventies- which were understood by the academics as ambiguities (Vilalva, Gala: 2001:55), hesitancies (Penna, 2001), oscillations, contradictions (Saraiva, 1996) or ambivalences. Thus, the policy towards South Africa presented oscillations as a consequence of the difference between principles and specific interests as a feasible adaptation of the clear and continuous objectives of the national development. With the oscillations Brazil tried to separate the approach to Black Africa from the traditional friendship with South Africa. Vilalva and Gala (2001:40) illustrate this with the image of “duas portas de abertura para a Africa: a porta negra e a porta branca”, being the idea clearly unfolded in the divergent opinions between Delfim Neto, theTreasury Minister and Gibson Barboza, the Foreign Minister. With the return to democracy in Brazil, Sarney’s government passed the so-called Sarney Decree of 1985 which gathered new prohibitions with previous ones, banning cultural and sports exchanges and oil, arms and military equipment exports. This decision, as well as the breaking off diplomatic relations that would be implemented by Argentina the following year, were the answer of both Latin American governments now democratic- to the aggravation of the repression of South African White government, not only within the country but also in the Southern African region. 12 Brazilian policy towards SA after 1994 During the 90s the Brazilian-African “honeymoon” showed its limits. The Foreign Policy suffered some changes, particularly because of the end of the import substitution model and the new neoliberal orthodoxy implemented by Brasilia. And even though diversification of external relations continued to be the objective in order to increase power in the international system, the scenario moved from Africa to Latin America and MERCOSUR. Furthermore, economic domestic problems, in Brazil and in the African states, contributed to the decline in the transatlantic relationship and the cooperative dreams vanished due to “afropesimism”. At that time, the “grand strategy” turned into a “selective policy”, fostering relations with those countries in conditions to reply to Brazil’s new requirements. The SouthSouth cooperation of the 70s turned into “strategic partnership”. Within this framework, diplomatic and political relations with the new South Africa became increasingly relevant. From having no policies towards Pretoria – particularly after the Sarney Decree- Brazil moved forward to consider South Africa as a Strategic Partner -in varied issue areas and particularly in the multilateral arena. The level of the exchanged visits gives an account of the relevance granted to the bilateral relation 6. President Cardoso’s visit to South Africa (1996) and the subsequent signing of eight bilateral agreements showed the increasing importance of these new ties. The strategy had two legs. The political dimension referred to the possibility of developing cooperative efforts in multilateral negotiations. The economic dimension aimed to foster the existing 6 On May, 1995, Foreign Minister Lampreia traveled to South Africa and he also accompanied the President on November 25-28 of the following year. Also crossed the Atlantic: Vice-President Marco Maciel (1999) and again Foreign Minister Lampreia (March 1-3, 2000). While from the South African counterparts traveled to Brasilia Foreign Affairs Minister Alfred Nzo (1995); Deputy Minister Aziz Pahad (1996); Vice-President Thabo Mbeki and Industry and Trade Minister Alec Erwin (1997); President Nelson Mandela (July 21- 22, 1998) and President Mbeki (December 12-15, 2000). 13 commercial potentialities7. Comparing the preparatory works, the mission’s development and its subsequent results with the visit of president Menem to South Africa the previous year, both government’s intentions towards South Africa appeared obvious: a high political-diplomatic profile and an outline of commercial diplomacy in the case of Brazil, and in the case of Argentina, a presidential strong urge to be in the limelight. Anyway, Brazil’s bilateral relations with South Africa did not end with the visit of Cardoso. Moreover, they were deepened to conclude on December 13, 2000, during Mbeki’s state visit to Brazil, with the signing of the South Africa and Brazil Joint Commission Agreement8, which was put into practice with the subsequent bilateral meetings in Brasilia (2002) and Pretoria (2003). In this context, it is interesting to highlight that Cardoso and Lampreia laid the foundations of a relation to which the new President Lula da Silva (2003) and his Foreign Minister Celso Amorim would continue deepening and expanding . The change of government promoted the deepening of relations with Africa and especially with South Africa, not only at the level of discourse but with specific actions. In all statements the re-launching of Brazil’s African policy was emphasized. President Lula and his foreign minister have gone to Africa in eight opportunities. South Africa still occupies the most important place, as a “spearhead” to develop a more solid relation with the other states of Africa. This was proved in his first trip in 2003, when he chose Pretoria for a visit. The identification and establishment of synergies and the 7 Brazil is South Africa's biggest trading partner in Latin America. Major South African exports to Brazil include precious and semi-precious stones and metal, anthracite and coal, iron and steel, miscellaneous chemical products, organic chemicals, aluminum, nickel, synthetic fibers, machinery and mechanical appliances, paper and paperboard. Brazilian exports to South Africa have steadily increased. Major Brazilian exports consist of vehicles and components, aircraft, machinery, mineral fuels, electrical machinery, animal and vegetable fats and oils, meat, ores, slag and ashes, organic chemicals and tobacco. 8 The first step in order to establish a Joint Commission between the two countries was taken during President Mbeki’s visit to Brazil on September, 1997, when it was suggested the establishment of an "institutional mechanism" to deepen South African-Brazilian relations. 14 managerial and political strategic convergence between both countries were pointed out9. In 2006, on February, during Lula’s fourth tour to Africa he went to South Africa again10. Being the Brazilian president who traveled more to South Africa and Africa, during his seventh trip he stopped in South Africa to participate at the IBSA Summit (India Brazil and South Africa) in october 2007. But Lula’s active presence in Africa is only one sign of Brazil’s African policy. Since the beginning of his administration he has received more than a dozen of heads of African states11 and African top level officials. During his administration more than 160 bilateral agreements with the African states were signed12 . On the other hand, Brazil’s trade with Africa have increased dramatically during the “Lula years”, from US$ 5 billions in 2002 to 20 billions in 200713. Brazil’s present foreign trade with Africa represents 7% of its trade with the whole world. What it is also interesting to note is that giving priority to the relations with South Africa, Brazil combines its bilateral diplomacy with its multilateral one, as will be seen with the cases of MERCOSUR-SACU and IBSA. Commercial Multilateralism Together with the intensification of bilateral relations with the now democratic South Africa, the negotiations for the signing of a Free Trade Agreement between MERCOSUR and SADC - though finally it was signed between MERCOSUR and SACU - started during Cardoso’s administration. 9 The cooperation comprises specific areas such as agricultural processing, industrial technology, biodiversity, biotechnology, energy, clean technologies, information and communication technologies, material research, space science and astronomy. 10 In November of the same year he attended the Heads of State Summit Africa -South America, in Abuja. 11 In 2004 Lula Da Silva met Mohammed VI, from Morocco and Joaquim Chissano.from Mozambique. In 2005 Brasilia was visited by the presidents of Algeria, South Africa, Congo, Gambia, Nigeria and Cabo Verde, in 2007 by the president of Senegal and by Libya’s Prime Minister and in 2008 by the President of Equatorial Guinea. 12 Between 1960-2002, 172 agreements were signed. 13 SECEX, Development, Industry and Foreign Trade Ministry, Brazil. 15 From the South African point of view, the association across the South Atlantic was part of its foreign agenda, and its interest was proved with actions like the visit of president Mandela to Ushuaia, during MERCOSUR Summit on July 24, 1998. Furthermore, on the occasion of a new MERCOSUR Summit on December 14, 2000, in Florianopolis, Brazil, the Project for an Agreement for the creation of a Free Trade Area between MERCOSUR and South Africa was signed, with the presence of the new South African president Thabo Mbeki. As a proof of Latin America’s intentions, the first combined commercial mission of businessmen of Mercosur’s four partners was sent to South Africa to promote products abroad14. At the same time, this mission constituted a challenge and a “test case” for the process of regional integration, as the combined commercial promotion offers a window of opportunities that would fulfill a Mercosur’s foundation aim: to integrate in order to compete in the world15. However and despite the strong initial step, the following negotiations have been slow, due to the difficulties to agree which sectors would benefit from reductions. By selecting South Africa, the Brazilian government went a step further from the traditional strategies adopted in its quest for a new African policy and a strengthening of the foreign relations established by Mercosur. Such choice suggests the inclusion of South Africa in a trilateral strategy (known as South-South-South diplomatic encounter) which includes India as well. Several international meetings attended by representatives from the three countries at the highest level lead to the creation of IBSA, in Brasilia on June 6, 2003, with the presence of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Brazil, Celso 14 Representatives of 35 Brazilian enterprises, 24 Argentinean and 15 Uruguayan traveled to South Africa, while there was a minimal participation of Paraguay, with the presence of its chargé d’ affaires. Mercosur’s delegation totalized 74 companies, 10 institutions and 91 people. 15 It should be highlighted that Argentine exports to South Africa consist mainly on food and agricultural products which are generally commercialized by multinational companies that decide where and how to sell according to their analysis of global markets. But, in Brazilian exports industrialized products prevail, with an important participation of enterprises such as Embraer (airplanes) and Daymler Benz (automobile industry). 16 Amorim, of South Africa, Nkosazana Dlamini Zuma and of India, Jaswanth Sinha. Since then, the Heads of State of the three countries have met in Brasilia (2006), Pretoria (2007) and New Delhi (2008)16. Final reflections In this new century, the model that implies the automatic and exclusive alignment with the central countries is beginning to show its flaws. The debate of a new development model for the countries of the South should not be postponed, despite domestic problems. The model imposed in the 1990s brought about, at least in Latin America, a marked inclination in the academic works on international relations. This tendency marginalized options in relation to, for example, African issues, which were labelled idle, not pertinent, weak or of no avail. Two factors contributed to consolidating such trend: a) the association between knowledge and power; i.e., “let us produce knowledge for the ruling power spaces”; b) the conditioning of the financial facilities that support these works. With this particular orientation, the doors to new ways of thinking about Latin America’s international insertion were closed. Therefore, this is not a work with the pretention of closing a chapter which may have proven the weaknesses of Argentina’s foreign policy towards Africa and South Africa or the brightness of Brazilia’s international insertion. On the contrary, a cluster of different issues should be addressed and fresh perspectives for the development of various new research lines of “variable geometry” should be envisioned; the international scenarios where the regionalization and globalization processes occur should be more profitably used. A Strategic Cooperation developing cooperative partnerships should be built by our 16 For more on IBSA see Lechini, Gladys Middle Powers: IBSA and the new South-South Cooperation, in NACLA Report on the Americas, New York, Vol 40, Nr 5, September-October 2007, pages 28-32. 17 governments, supported and shored up by the interweaving of interests in civil society. This cooperation built on policies resulting from shared values, ideas, and principles should produce a spillover effect on other areas such as trade and investment, defence and security, and on civil society institutions. Bibliography - Ket, Dot (2006) South-South Strategic Alternatives to the Global Economic System and Power Regime (Amsterdam: Transnational Institute). - Lander, Edgardo (comp.) (2000) La colonialidad del saber: eurocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Perspectivas latinoamericanas (Buenos Aires: Ediciones CLACSO) - Lechini, Gladys (comp.) (2008a) Los estudios afroamericanos y africanos en América Latina. Herencia, presencia y visiones del otro (Córdoba: Ediciones CLACSO/CEA). - Lechini, Gladys (ed.) (2008b) Globalization and the Washington Consensus (Buenos Aires: Ediciones CLACSO). - Lechini, Gladys (2006) Argentina y África en el espejo de Brasil. ¿Política por impulsos o construcción de una política exterior (Buenos Aires: Ediciones CLACSO). - Lechini, Gladys (2001) África desde Menem a De La Rúa: continuidad de la política por impulsos. In CERIR (ed.), La política exterior argentina 1998-2001. El cambio de gobierno ¿Impacto o irrelevancia? (Rosario: Ediciones CERIR), Vol. III. - Lechini, Gladys (1995) Las relaciones Argentina-Sudáfrica desde el Proceso hasta Menem” (Rosario: Ediciones CERIR). - Miranda, Roberto (2003) Política exterior argentina. Idas y venidas entre 1999 y 2003 (Rosario: Ediciones PIA). - Penna, Pio. (2001) Africa do Sul e Brasil: diplomacia e comércio (1918-2000). In Revista Brasileira de Política Internacional, a.44, nº 1. Brasilia: Instituto Brasileiro de 18 Relacões Internacionais, p. 69-93. - Programa de Naciones Unidas para el Desarrollo (2004) Forging the Global South, Día de Naciones Unidas para la Cooperación Sur-Sur, 19 de diciembre. Disponible en el sitio web: http://tcdc.undp.org/doc/Forging%20a%20Global%20South.pdf - Sombra Saraiva, José Flavio (1996) O lugar da Africa. A dimensão atlantica da politica externa brasileira (de 1946 a nossos dias) (Brasilia: Ed. UNB). - Vilalva, Mário, Gala, Irene Vida (2001) Relações Brasil Africa do sul: quatro décadas rumo à afirmação de um parcería democrática (Brasilia: Cena Internacional), a. 3, nº 2. - Worsley, Peter (1972) El Tercer Mundo una nueva fuerza vital en los asuntos internacionales (Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno Editores). 19