LANGUAGE AND VIOLENCE IN MALAWIAN POLITICAL DISCOURSE

advertisement

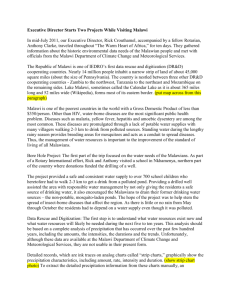

LANGUAGE AND VIOLENCE IN MALAWIAN POLITICAL DISCOURSE: A CONTEMPORARY HISTORICAL AND ETHICAL PERSPECTIVE Edrinnie Kyambazinthu & Fulata Moyo, University of Malawi, Chancellor College, Box 280, Zomba A paper presented at the International Conference on Historical & Social Science Research in Malawi: Problems and Prospects, 26-29 June 2000 at the Great Hall, Chancellor College, Zomba, Malawi. 1 Introduction This paper aims at tracing and discussing the culture of violence in Malawi through political discourse of Malawian politicians. The period under review starts from the referendum period (1994) to date and the contention is that even under the new political dispensation the violence has not been abated. The paper will analyse samples of natural speeches uttered by the various political players during this period even though focusing mainly on the ruling United Democratic Front of Malawi during 1999 election campaign when the opposition party was not given a platform to answer back. The language used by the President, district governors the regional governors through various media will be analysed to illustrate how political discourse can lead to violence. The paper premises that language changes manifest social changes and that the reverse is also true. The debatable concept that language influences thought and that if language is manipulated, so are the processes of thought (Thorne 1997)1 also holds true here. Politicians through what they believe, use language to encourage voters and their supporters to identify with their world view. All situations which are threatening or involve power play between individuals are of interest. Also the role played by partisan media houses in propagating violent propaganda will also be addressed. The paper is divided into three sections. Section one contextualises the study within the ethico-moral responsibilities and obligations of public speakers, section two reviews some of the literature on the subject and section three presents data on linguistic strategies used in politically-based violent language. 2 Contextual Background: Malawi and the Culture of Love and Tolerance The Weekly News, (9-12 July 1999:6) reported that the Censorship Board says it has noted with concern the proliferation of indecent, obscene, offensive and harmful publications, music, songs language and other public performances within the Malawian society. In a press release sent to media houses Chief Censoring Officer, Geofrey Kanyinji says as custodians of public morality, the Board wishes to condemn such acts in the strongest terms and appeals to everyone to refrain from promoting obscenity, indecency, hatred and violence among morally upright and peace-loving Malawians. The Censorship Board also appeals particularly to all entertainers, artists, cartoonists, drama groups, song writers and singers, bands, electronic, print media and indeed all Malawians to promote a culture of peace, tolerance, love reconciliation and forgiveness. Hate songs, violent songs, hate speeches, hate talk, hate articles in papers, hate interviews on radio or television do not promote peace and love and therefore should not be condoned or promoted by any peace loving Malawian, adds the release. 1 S, Thorne, Mastering Advanced English Language.(London, MacMillan, 1999). 2 Malawi as a God fearing nation should not be subjected deliberately by entertainers, artists, broadcasters, print media and song writers to songs interviews, articles or images which promote hate, tribalism, ridicule, violence, vengeance and sadism, it adds. At this sensitive time of our beloved mother Malawi, we urge artists to sing songs of love and reconciliation, peace and forgiveness, drama groups depict plays whose heroes are people engaged in peace and reconciliation, reporters and media to condemn violence and interview on how Malawi can forge ahead in peace and reconciliation, development and prosperity, eradicate disease, ignorance and poverty. Do not glorify trouble makers, violence or foul mouthed speakers. Ignore such people or condemn their actions. Unbalanced interviews also promote hatred, the Chief Censoring Officer says. He also advises entertainers, artists’ drama groups, song writers and singers, print and electronic media, to promote peace, tolerance, love, reconciliation and forgiveness, and to condemn the evils of hate, tribalism, regionalism and vengeance. Let’s build Malawi on a culture of peace, love tolerance and forgiveness the release says. 2.1 Tolerance Vs Intolerance: Moral and Ethical Issues In the above press release, the Censorship Board echoes the general understanding of Malawians that they are supposed to be God fearing in their day to day living especially as they interact with others 2. This understanding of Malawians as God fearing has over a period of time implied so many things. For example, some people especially a majority of Christians believe that Malawi is a Christian country. This belief is basically rooted in the fact that over 70 percent of the Malawian population claim to be Christian. This is a population that is affiliated to one church or another. The belief that Malawi is a Christian country was so much propagated by the former head of state Dr Hastings Kamuzu Banda who was himself a Church Elder of the Church of Scotland, the parent church to Church of Central Africa, Presbyterian (CCAP), Blantyre Synod. This belief has also to do with the historic missionaries’ impact in the education system, political history, health and other areas of Malawian life. Yet, it would be an oversight to call Malawi a Christian country despite the big percentage of Christians. To call a country Christian would imply that it is a Theocracy where whoever is a human head is standing in place of God who is the real Head and the country itself is run on God’s law as enshrined in the Christian who upholds the Christian country. Yet this does mean that Malawi should not strive for a culture of love, tolerance, forgiveness and reconciliation. Whether Christian or not, Malawi as a nation consists of so many people of different backgrounds, beliefs and attitudes and it is with love and tolerance that such a diversity can hope to work together for the common good. As any human society, Malawian societies face a conflict between ethics and politics which is made inevitable by the double focus of moral life between the individual’s life and his/her social life. According to Niebuhr (1987)3 “from the perspective of society the highest moral ideal is justice. From the perspective of the individual the highest ideal is unselfishness”. These two moral 2 The Malawi Vision 2020 Mission statement alludes to the same fact Richard H, Niebuhr, “ The conflict between individual and social morality”, R Gill, A Textbook of Christian Ethics, Edinburgh, T&T. Clark Lt., 1985, p 251 3 3 perspectives should not be looked at as mutually exclusive of each other. Though not easily harmonized, they need to be inclusive of each other if, for example, Malawian societies are not work towards a common good. Every Malawian should strive “to act justly and to love mercy and to walk humbly with each other (sic)” as Prophet Micah would appropriately put it (Micah 6:8) Although the Malawian constitution guarantees freedom of expression or speech, legal and ethical responsibilities must also be borne in mind by politicians. From a communication point of view, ethical issues centre on value judgements concerning degree of rightness and wrongness and wrongness and badness in human conduct. Society expects certain standards from our politicians along similar parameters. That is, public speakers are responsible to their listeners for what they say in terms of truth and accuracy of information given. It is therefore unethical to utter lies or statements which cannot be substantiated. Whilst it is acceptable to hold or advocate for a particular position or stance, facts are to be presented for the audience to analyse and make decisions. Legal responsibilities include refraining from any communication that may be defined as clear and present danger such as inciting people to riot, refraining from using obscene language and language that defames the character of another person by making statements that convey an unjust, unfavourable impression without solid evidence4. Malawi is a country that is divided into three regions: northern, central and southern regions which need to work together if at all it is to be indeed the government of the people, by the people and for the people as Abraham Lincoln would define democracy. Unfortunately this working together for the common good has not been a reality among the different regions which also entail different political parties. There has been so much intolerance expressed in so many segregative attitudes like hurtful language by Malawian politicians who through what they believe, use language to encourage voters and their supporters to identify with their world view. In turn this influence creates a sense of belonging that has no sympathy for the other. 3 Literature Review: Language, Power and the Culture of Violence Conceptually we are using the word political-based violence in general terms as stated by Brekle (1989)5 to mean actions carried out between rulers and also between individuals, with the intention of injuring the other party by means of physical violence or psychological pressure or aggression. According to Brekle (1989:81)6, someone wages war on others by means of words. Someone also seeks adversely to affect the conditions of other people’s lives, to obtain power over them, to rob them of human dignity or, in the extreme case, of their physical existence, using among other means words, statements and texts. Wodak (1989)7 states that language only gains power in the hands of the powerful per se. Specific language symbolizes the group or person in power. Fights about the status or discrimination of a person symbolize power struggles. 4 R. F. Verderber, The Challenge of effective speaking, Califonia, (Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1985) H. E. Brekle, H. E. War with words. In R Wodak (ed.), Language, Power and Ideology: Studies in political discourse.(Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 1989)pp 85-86 6 H. E. Brekle, War with words. 1989 7 R. Wodak, The Power of political jargon-“a Club -2” discussions. In R. Wodak Language power and ideology. 1989 pp137-163 5 4 Apart from the Censorship Board’s press release, some authors in Malawi have noted the effects of speech acts. Chimombo (1999:215) notes the disturbing rise in hate speech leading to violence as evidence that speech can, and often does provoke action not just in Malawi but also in established democracies. Kamwendo (1999 & 2000) has documented the inflammatory language used by the MCP led government and the actions of the opposition parties that have led to violence in Malawi and the lessons to be learnt from such actions in order for Malawi to sustain the young democracy. Since hate language has been used by both young and established democracies, the paper wants to emphasise on the ethical and moral responsibilities and obligations our leader as public speakers have. It has been noted by Kamwendo (19998 & 20009) that the 30 years of dictatorship in Malawi were characterized by hate language against those who opposed the Malawi Congress Party (MCP). Our contention is that Malawi has through the so called democratic or open society period experienced both physical and psychological violence perpetrated by both camps. This is testimony that the culture of intolerance in Malawi is growing and that no real transformation has taken place to uproot this evil. Violence in the form of physical fights between warring parties and the burning of each other’s vehicles or houses because of intolerance and the desire for power has been reported. Words have played a crucial role in this violence to convey the desired effect on the intended audience. The use of abusive language during the referendum period and now testify to this as can be seen in Table 1. G H Kamwendo, “Inflammatory political language: A threat to peace and democracy in Malawi”. Unpublished paper read at the 21st Southern African Universities Social Science Conference (SAUSSC), Malawi, 29 November-3 December 1999 9 G H Kamwendo, Uses and abuses of language durig election campagn. In M> Ott, K. M. Phiri and N. Patel, Malawi’s second democratic elections. Processes, problems and Prospects.(Blantyre, CLAIM, 200), pp 186-203 8 5 Table 1: Sample abusive & intimidating language used during the referendum and the multiparty democracy era Malawi Congress Party Era United Democratic Front Party Era Vernacular Word Used English Vernacular Word used English *Bongololo *Anyani Millipede Monkeys Meat for crocodiles Confusionists Baboons Fools Dogs Curios or mentally retarded person To urinate into the Bishop’s mouths Thugs or rebels Get killed Openga Mafia Ninja Mad person Crooks/killer Trouble shooter Insane Tattered curtains Brutal party Useless wind instruments Warlords Party of doom *Ankhweri *Zitsiru *Agalu *Ziboliboli (sena language) *Kukozera ma Bishop mkamwa *Zigawenga Tikonza Makatani oyoyoka Chipani cha nkhanza Zitolilo Wina alira Wina amwa termic Kuntunda Owinawina Enemies of democracy Criminals Most powerful ruler Obvious winner *Source: Kamwendo (199910) Before going any further it is imperative to point out that initially we had planned to use MBC as our main source fro data collection but we discovered that despite the general understanding that there is now transparency in Malawi, some ‘privileged’ information is not ready accessible. Why we were not allowed to have access to presidential speeches from MBC, can only be deducted from the popular understanding that exits within Malawi. So we had to use other means like Article 19 Final Report11, the oral speeches we listened to backed up by newspapers articles in pro-UDF papers, The Nation, and the pro-MCP- The Daily Times and Press Releases. The recent Kachere Series publication of Malawi’s Second Democratic Elections especially the article by Gregory H. Kamwendo on “Uses and Abuses of language During Election Campaign” was very helpful. We just hope that as our democracy matures, there will be real transparency. 10 G H Kamwendo, Inflammatory political language, 1999 At the crossroads: Freedom of expression in Malawi. The final report of the 1999 article 19 Malawi Election Media Monitoring Project, International Centre against Censorship, March 2000 11 6 4 Violent Language: Linguistic Strategies Used In analyzing the linguistic means used to denote violence in the interest of power, speech acts by the authorities in power (statement, question, command, promise, threat etc) are important because they enforce their interests. Of important to this paper is the intention of the utterance and its goal. According to Brekle (1989)12 some speech acts are associated with special supporting conventions that enforce one’s power and serve his/her interests such as insult and slander, condemnation, etc. The use of words-put together into appropriate texts and propagated through the media is regarded as a powerful means of exerting influence in order to advance the politicians’ goals. It is generally recognized that the feeling evoked, be they feelings of fear or timidity, the will to win or the impulse to destroy, depend on the words used. And these feelings are of course evoked by particular groups in positions of power who are interested in the emergence or continuance of a particular state war. The whole idea of abusive language during the referendum period and now testify of this. One would say that Malawians are tolerant in that we have not yet seen full fledged war despite this but that does not mean that violence does not exist in Malawi. Moreover who knows what will happen next if this language violence continues? As already noted Malawi is not unique in the use of violent language or propaganda. According to Brekle (1989), the methods and ingredients of British propaganda against German can be reduced to eight basic features: stereotypes, negative name calling, selection and suppression of facts often with palliative terms, reports of cruelty, slogans, one sided reporting, unmistakably negative characterization of the enemy, and the so called bandwagon effect. These basic features can be integratively used as a framework for analyzing some of the features noted in Malawi politicians’ speeches. Stereotyping and Names with Negative Cannotations President Muluzi has constantly rerred to the MCP as chipani chankhanza (brutal party), party of doom, or a dying party. In other words MCP will never change and Malawians should never forget what this party stood for in the past 30 years or so. The perpetual imagine of terror, brutality and destruction, lies and despotism become apparent when UDF factionaries use words such as these. Apart from stereotyping, the ruling UDF party have used names with negative connotations. The president has also referred to the MCP as decadent or dilapidated party when he referred to it as makatani oyoyoka reminiscent of a house that is old with useless thread bare curtains. Mr Kachimbwinda, the then central region governor of the UDF party lashed at Tembo and called him a Mafia whilst he Mr Kachimbwinda was a Jinja who would deal with crooks like John Ungapake Tembo. The use of personal names like this should be noted as provocative at its best and demeaning to say the least. Mr Kachimbwinda’s speech was fiery and cruel to a person who had no platform to answer back on the radio. The imagery of a Ninja evokes fear amongst evil doers. Whilst the language was creative in terms of evil vs goodness, moral vs immoral, it also provoked images of violence of the underworld (Mafia). Tembo was also referred to as a warlord by the Weekly Times of 2-4 February 1999. 12 H E Brekle, War with words, 1989. p81-90 7 The print media also played a crucial role in this war of words. The Mirror of 17 December 1998 reported that People in the Northern Region who out of blind emotion (felt) that Chihana was the Messiah to free them from the shackles of poverty and degradation, have now realized that the man is to totally incapable of any meaningful thing and in their mass they (the people) are moving to the ruling United Democratic Front (UDF) which for the first term in government has shown its seriousness in developing the region (Article 19 Report, 2000:62). This, in light of how people voted cannot be substantiated (see Patel 2000a13 & b)14. Selection and suppression of facts The selection and suppression of facts entails the presentation of half truths which might end up being on truth at all. Yet genuine democracy requires that there be trust amidst the people. Real trust can only be built on truth not on falsehood. The selection of those facts which work against certain people in this case, the opposition tends to mar the image of the opposition. It would be in the spirit of transparency if the bad image of the opposition presented was based on the truth but as it were the art of selecting and suppressing facts is systematically done so as to present the opposite image. For example, ARTICLE 19 Report (2000:48) reports that the ruling UDF government embarked on a campaign of disinformation. The Voter Action Plan o the UDF when the Electoral Commission wanted to break up the electoral alliance between AFORD and MCP reported on the non-existent Northern Region Solidarity Movement press release which “vehemently rejected (sic) the dubious electoral alliance and questioned (sic) Chakufwa’s mental sanity and called the readers’ attention to the fact that MCP is just bent on using and exploiting Gwanda and through him the entire Northern Region” (Weekly Time, 10 February 1999). Chihana is said to have pawned his party (wapinyolisa chipani), he is a man who is power hungry and would stoop so low as to sellout the MCP and betray the northerners who had entrusted him with the party. This misinformation does not only tarnish the image of the reported, it questions and insults Chihana’s intelligence, sanity, merit and authority. It also brings doubt on the people who would otherwise be supporters of the party concerned. Moreover it waters seeds of regionalism and intolerance. It is unfortunate that a small poverty-stricken country like Malawi can have parties that are distinguished or regional boundaries, but to deliberately foster such a division is very undemocratic and unacceptable. What does freedom of association mean if AFORD has to do with people from the north therefore a northern party, MCP centre therefore a central party and UDF south and therefore a southern party? This is an attitude which deliberately appeals to the emotions so as to discourage a rational and critical mindI belong to such a party, therefore, I will support everything about that party? This attitude works against the reality of a pluralistic society. Two other damaging but unsubstantiated claims by the government was that ZANU-PF women were going to smuggle arms into Malawi to help MCP and John Tembo seize political power under the pretext that Malawi is in danger of becoming an Islam Nation (Weekly News, 27 January 1999) and also that the opposition was planning to kill Muluzi (The Mirror 2000). Both issues gained wide coverage through the national radio and Television Malawi (TVM). The President even commented on the coup plot without investigating the truth of the matter. When the falsity of the story was discovered moral and legal responsibility of the people in power and the journalist who wrote the story was put in question. The idea of planting fear in Malawians was based on N Patel, The 1999 elections. Challenges and reforms. In Ott et al. Malawi’s second democratic elections 2000a. pp22-52 14 N Patel, Media in the Democratic and electoral process. In Ott et al Malawi’s second democratic elections, 2000b.pp158-185 13 8 the fact that MCP had allegedly always wanted to invade the country using the Malawi Young Pioneers, something one would still call hearsay in the absence of tangible evidence. The Weekly News of 2-4 February 1999 stated that Tembo had sent Ntaba and Mputahelo to see Dhlakama to work out a strategy (sic) on destabilizing Malawi which would involve deploying Malawi Young Pioneer cadres from their Mozambique hideout to unleash a reign of terror through armed robbery and outright terrorist attacks on government installations and civilians. Rhetorical evocations According to Edelman (1977:13)15 political facts are especially vivid and memorable when the terms used that denote them depict a personified threat: an enemy, deviant, criminal, or wastrel. It is through metaphor, metonymy and syntax that linguistic references evoke mythic cognitive structures in people’s minds. Edenlman (1977:110, argues that public language takes many political forms. Exhortation to patriotism and to support for the leader and his/her regime are an obvious from. Other forms include: (1) terms classifying people (individually or in group) according to the level of their merit, competence or authority. These forms justify status levels, but purport to be based on personal qualities: intelligence, skills, moral traits or health. (2) terms that implicitly define an in-group whose interests conflict with those of other groups e.g. issues of loyalty, references to the reliability or hostile stance of individuals. Such terms permeate the everyday language of the political parties. Their employment by any group, together with the provocative behaviour they encourage, also elicits their counter use. Indeed, as argued by Eldelman (1977:115) in tense times, political leaders make statements that shock thinking people: threats to employ terrorism and kill the opposition/ruling leaders and rhetoric exalting violence. Such language typically consists of short incomplete sentences and confounds reasons and conclusions to produce categorical statements. It also repeats idiomatic phrases frequently, and relies upon sympathetic circularity among adherents of the movement to induce support for the social structure the politicians favour. Sornig (1989 cites Bork 1970:9) state that words can, in fact, be used as instruments of power and deception, but it is never to words themselves that should be dubbed evil and poisonous. The responsibility for any damage that might be done by using certain means of expression still lies with the users, those who, not being able to alter reality, try interpretative strategies to change its reception and recognition by their interlocutors”. The imagery of the opposition as enemies of democracy, deviants, criminals, warlords and good for nothing people is clear from the misinformation that was transmitted by the politicians during the 1999 election campaign. It would not be far fetched to believe that some people in the electorate believe these provocative speeches. Use of Pro-UDF slogan UDF boma (UDF! Government), Bakili! Kuntunda (Literary means: most highest in the land!). Implying that Bakili is better than anyone else and there is no one else to equal him, owina wina (obvious winner), opanda nkhanza (not cruel. Here Muluzi is compared to Dr H. Kamuzu Banda who was notorious for 15 Edelman, M. 1977. Political language: words that succeed and policies that fail. New York: Academic Press 9 imprisonment without trial), oyenda mmaliro (Somebody who attends funerals or a compassionate person unlike the former president Dr Banda who didn’t attend funerals), wachitukuko (a propagator of development). This is also selection and suppression of information with palliative terms. This is typical of politicians. As argued by Holly (1989:115)16, Politicians are not reputed to be personifications of credibility. The image of the politician who doesn’t instill confidence has a long tradition. Aristotle’s tyrant seizes power by defaming the nobles and stays in power merely by playing the part of a good king. Macchiavelli’s ‘principle’, the prototype of the modern bad politicians, has no scruples about being hypocritical. There were times when the word politic and its related words in European languages seemed to be synonymous with feigning or dissembling. Partisan reporting One-sided reporting done by the pro-government Malawi Broadcasting Corporation (MBC) covered only the UDF campaigns. None of the opposition parties were aired. The allowed for a lot of misinformation about the opposition party through the radio and some pro-UDF newspapers which were set up specifically to decampaign the opposition (see Article 19 Final Report 2000:96)17. Using unmistakably negative characterization of the enemy and the so-called bandwagon effect, for example, vote for UDF or no development in your area, the government was able, owing to the agreement of press and the government, to exert great influence on the people. In the Malawian context, Dr Bakili Muluzi during the campaign period referred to leaders of the opposition as zitoliro (noisy flutes that carried empty words and therefore should not be taken seriously). This metaphor was used to deny freedom and dignity to other political parties who were already suffering from lack of funds and internal bickering. The same metaphors enforced conformity to the UDF norms and encouraged ill-treatment of the distressed parties. During his second swearing-in ceremony, the president warned the opposition and challenged them that if they dared to start war in Malawi then he was prepared for them as he had enough weaponry to destroy them. They should just dare and they will see. He derided them by saying wina alira (winner takes all and the loser has to cry) or if someone is not happy today then something is wrong with him. The division within MCP is fighting… to detail the general elections and take over power by hook as the party loses support on a daily basis to the UDF, currently riding on an enviable wave of part popularity.” Article 19 Final Report (2000:96-97) states that thirteen out of 24 issues of This is Malawi were expressly party-political- all favouring the UDF and antagonistic to the opposition parties, especially the MCP. The titles related to the unsubstantiated story of the MYP- MCP-Renamo Plan to overthrow the UDF government, the story of the split in the MCP over the MCP-AFORD Alliance. Titles such as “The Dying MCP Resorts to Lies” outlined the work of the MCP paid lobbyist (Martin Minis) in London. The title “Hell Hath No Fury Like a Scorned Woman” was a derisive article about John Tembo’s position in the Alliance and the division within the MCP. Werner Holly, ‘Credibility and political language’ In R. Wodak, (ed.) Language, power and ideology 1989, pp115 17 At the Crossroads, freedom of expression in Malawi, 2000, pp96 16 10 Admittedly, “it was not clear how a magazine that goes out of its way to publicise the fact that Malawi is politically unstable and that a coup plot is being planned when there is no evidence provided actually benefits tourism and foreign investment or improves the country’s image abroad. Such party political reporting does an injustice to the nation as a whole” (Article 19, 2000:97) President Muluzi on inauguration day stated in Chichewa that: Ngati alipo wina sakukondwera ndi siku laleroli ndizake zimenezo. (If others are not happy with this day then they have a problem). I will not allow anybody, because they have lost an election to start civil strife in this country. I have heard that some have threatened to go into the bush! Ayesesere awone, ndiwaphulisa! Honestly, just let them try it. I will blow them up, try it and see. Muzaona ndege sopanda mapiko zikubwera. You will see aeroplanes without engines come against you. We want peace in Malawi. In March, 2000, the Centre for Advanced Research on Education and Rights (CARER) issues a press release denouncing the practice of women dancing at political rallies. In this press released, Vera Chirwa argued that women-dancing does not respect the dignity of women and if not checked would lead to the creation of another dictatorship. Responding to this, President Muluzi who during the 1993-94 campaign denounced the dancing women for Kamuzu as an oppression that his party if voted into power would forthrightly get rid of it, denounced Vera Chirwa as someone who has herself political ambitions. He argued that if women do not dance at political rallies where else does someone like him identify those to have ministerial positions? The president’s remarks were not only unfortunate, they were also very gender insensitive. It was as if women have to dance in order to be recognized and to deserve promotion. The president depicted the women of Malawi as sex objects behind the façade of cultural practices of Malawi while the male counterparts do not have to prove anything in order to be recognized. This was difficult to comprehend for some women especially in this day and age of human rights for both female and male: does our president still think that we have no rights to some job opportunities like our male colleagues? What was particularly disturbing were the unchecked violent interjections from the UDF women at the rally who kept on castigating and deriding Mrs Chirwa as a prisoner (mkaidi) and urging Muluzi to send her back to where she belongs (prison). Mrs Chirwa did not deserve such psychological torture for expressing her views. Besides, lack of consensus is not always negative opposition! Despite calls from the Censorship Board hate language has continued. On Monday, 19 June, 2000, President Muluzi addressing the people at Makanjira in Mangochi, said in Chichewa again, “Wina alira lero. Ndithu wina amwa mankhwala a makhoswe (someone is going to take termic or commit suicide), tsiku lake ndi lero (today is the day). Otsutsa boma ndi openga (members of the opposition are mad people)… akuti Mau Mau, chani …asiyeni adzaone ndege za nkhondo zopanda ma injeni. (They are talking about Mau Mau, what is Mau Mau, just watch them, they will see war planes without engines if they are not careful) siine wosewere naye iyayai, (they cannot play around with me) sindili ndekha ( I am not alone, I have friends who can assist me). Ironically, after this emotional speech and after fanning people’s emotions with these remarks, in typical style, Muluzi continued his speech by talking about the need for peace and working together as Malawians in developing our country. Here Muluzi contradicted himself18. His opening remarks showed a spirit of intolerance and hate. It was said with emotion thus 18 The president also contradicts himself when he says that all MPs must belong to UDF if the people want development in their areas but at the same time he moans that the opposition is too weak!! 11 sparking the emotions of all those who support him and his party. It sounded very hypocritical when he went on to talk about working together for the common good. He even went ahead and selected a candidate for MCP for the August convention in the name of John Tembo because he is the only one who makes worthwhile comments in the MCP camp. Even his advice evokes a lot of suspicion and smacks of the spirit of divide and rule and the return to one party state with a weak opposition. When did John Tembo, the Mafia become a Ninja (after the footsteps of Maurice Kachimbwinda?). During the 1993-94 campaign, JZU Tembo was referred to as a very cruel uncle, the most influential of the Threefold political family. Has he suddenly become a saint and democratic politician? Has the president forgotten about the terror that the name JZU used to cause during the MCP-led government? This opportunistic change of mind by our leader brings so much doubt in our minds as his subjects. 5 Concluding Remarks This paper aimed at tracing the culture of violence in Malawi through political language during the post colonial era. The paper has shown that violence can be traced from the Banda era and especially during the referendum period but that even during the new democratic era hate language has continued to be a political weapon. Various strategies used by politicians to perpetrate violence have been outlined. It is unfortunate that the opposition was not given an opportunity to reply which makes this paper rather one sided. Malawians are getting accustomed to the view that Malawian opposition leaders are untrustworthy, criminals, warlords, incompetent etc, while untrustworthy politicians within the ruling party are given trust through political discourse, propaganda and slogans. The paper has attempted to emphasise that wrong values, beliefs and perceptions are being transmitted about issues which sometimes do not exist whilst chronic socio-economic and political problems are trivialized through political discourse. The responsibilities and obligations of the politicians as having a moral duty to uphold democracy and stick to issues is apparent when the hate language is misguided and aimed at nonissues instead of concentrating on good governance, issues of rule of law, economic development and developing ideology that they can sell to the electorate. Unless the politicians see their moral and ethical responsibilities, Malawi runs the danger of continuing developing violence and intolerance to the extent of anarchy. It will be important for the political parties to guard their language and that development does not come from a war of words but sticking to the real business of governing the country and concrete reform programmes. 12 REFERENCES Chimombo, M. 1999. Language and politics. Applied Linguistics. Vol 19 215-232. Edelman, M. Political language: words that succeed and policies that fail. New York: Academic Press, 1977. Gill, Robin, A textbook of Christian ethics. Edinburgh, T & T Clarke Ltd. 1985. Kamwendo, G.H.. 1999. Inflammatory political language: A threat to democracy in Malawi. Paper presented at the 21st Southern African Universities social sciences conference (SAUSSC). Malawi, 29 November – 3 December. Martin Ott, Kings M. Phiri and Nandini Patel (eds.), Malawi’s Seconds Democratic Elections: Problems and Prospects, Blantyre: CLAIM, 2000. Niebuhr, R.H., “The Conflict between individual and social morality”, Robin Gill’s A Textbook of Christian Ethics, Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark Ltd., 1985, p. 251 - 268 Thorne, S. Mastering Advanced English Language. London, MacMillan, 1997. Wodak, Ruth (ed.), Language, power and ideology: Studies in political discourse, Amsterdam, John Benjamins, 1989. 13