Chapter 10: Motivation and Coaching Skills

advertisement

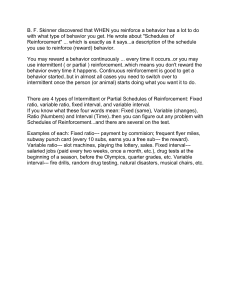

Chapter 10: Motivation and Coaching Skills KnowledgeBank, p. 294 Behavior Modification and Motivational Skills Behavior modification, a well-known system of motivation, is an attempt to change behavior by manipulating rewards and punishment. Behavior modification stems directly from reinforcement theory. Since many readers are already familiar with reinforcement theory and behavior modification (often shortened to “behavior mod”), we will limit our discussion to a brief summary of the basics of behavior modification, and focus instead on its leadership applications. An underlying principle of behavior modification is the law of effect: Behavior that leads to a positive consequence for the individual tends to be repeated. In contrast, behavior that leads to a negative consequence tends not to be repeated. Leaders typically emphasize linking behavior with positive consequences, such as expressing enthusiasm for a job well done. Behavior Modification Strategies The techniques of behavior modification apply to both learning and motivation; they can be divided into four strategies. Positive reinforcement, which rewards the right response, increases the probability that the behavior will be repeated. The phrase increases the probability means that positive reinforcement improves learning and motivation but is not 100 percent effective. The phrase the right response is also noteworthy. When positive reinforcement is used properly, a reward is contingent upon the person doing something right. If the company achieves a high-quality award, the company president might recognize the accomplishment by giving a bonus to all. Authorizing a bonus for no particular reason might be pleasant, but it is not positive reinforcement. Avoidance motivation (or negative reinforcement) is rewarding people by taking away an uncomfortable consequence of their behavior. It is the withdrawal or avoidance of a disliked consequence. A leader offers avoidance motivation when he or she says, “We have performed so well that the wage freeze will now be lifted.” Removal of the undesirable consequence of a wage freeze was contingent upon performance above expectation. Be careful not to confuse negative reinforcement with punishment. Negative reinforcement is the opposite of punishment: It involves rewarding someone by removing a punishment or an uncomfortable situation. Punishment is the presentation of an undesirable consequence, or the removal of a desirable consequence, because of unacceptable behavior. A leader or manager can punish a group member by demoting him or her for an ethical violation such as lying to a customer. Or the group member can be punished by losing the opportunity to attend an executive development program. Extinction is decreasing the frequency of undesirable behavior by removing the desirable consequence of such behavior. Company leaders might use extinction by ceasing to pay employees for making frivolous cost-saving suggestions. Extinction is sometimes used to eliminate annoying behavior. Assume that a group member persists in telling ethnic jokes. The leader and the rest of the group can agree to ignore the jokes and thus extinguish the joke telling. A guiding principle for motivating workers through behavior modification is that you get what you reinforce. If the leader or manager wants workers to perform in certain ways, such as answering customer inquiries over the Internet within twenty-four hours, that particular behavior must be reinforced. Reinforcing other behaviors, such as handling many inquiries, will not lead to the performance improvement sought. In a behavior modification program in a bank, supervisors gave feedback and recognition in front of coworkers to tellers who performed certain customer service behaviors. These included using the customer’s name, providing a statement balance, and making eye contact. Customer satisfaction as measured by a survey increased after these customer service behaviors were reinforced.[1] Rules for the Use of Behavior Modification Behavior modification in organizations, often called OB Mod, frequently takes the form of a companywide program administered by the human resources department. Our focus here is on leaders’ day-by-day application of behavior mod, with an emphasis on positive reinforcement. The coaching role of a leader exemplifies the application of positive reinforcement. Although using rewards and punishments to motivate people seems straightforward, behavior modification requires a systematic approach. The rules presented here are specified from the standpoint of a leader or manager trying to motivate an individual or a group.[2] Rule 1: Target the desired behavior. An effective program of behavior modification begins with specifying the desired behavior—that which will be rewarded. The target or critical behaviors chosen are those that have a significant impact on performance, such as asking to take an order, conducting performance appraisals on time, or troubleshooting a customer problem. According to Fred Luthans, the critical behaviors are the 5 to 10 percent of behaviors that may account for as much as 70 or 80 percent of the performance in the area in question.[3] Rule 2: Choose an appropriate reward or punishment. An appropriate reward or punishment is one that is (1) effective in motivating a given group member or group and (2) feasible from the company standpoint. If one reward does not work, try another. Feasible rewards include money, recognition, challenging new assignments, and status symbols such as a private work area. Stock options are widely used to motivate executives, and sometimes workers at all levels. Companies such as Starbucks Corporation, Cisco Systems, First Tennessee Bank, and General Mills offer stock options for all employees. The expectation is that each recipient of a stock option will work hard to improve company performance so that the stock price will rise and he or she will benefit personally. Most of the rewards mentioned so far are extrinsic. However, intrinsic rewards can also be part of behavior modification. A person who performs well might be offered the opportunity to engage in more work that is exciting or fun, such as being a company representative at a trade show. When positive motivators do not work, it may be necessary to use negative motivators (punishment). It is generally best to use the mildest form of punishment that will motivate the person or group. For example, if a group member reads a newspaper during the day, the person might simply be told to put away the newspaper. Motivation enters the picture because the time not spent on reading the newspaper can now be invested in company work. If the mildest form of punishment does not work, a more severe negative motivator is selected. Written documentation placed in the person’s personnel file is a more severe punishment than a mere mention of the problem. Rule 3: Supply ample feedback. Behavior modification cannot work without frequent feedback to individuals and groups. Feedback can take the form of simply telling people when they have done something right or wrong. Brief paper or electronic messages are another form of feedback. Be aware, however, that many employees resent seeing a message with negative feedback flashed across their video display terminals. Rule 4: Do not give everyone the same-sized reward. Average performance is encouraged when all forms of accomplishment receive the same reward. Say one group member makes substantial progress in providing input for a strategic plan. He or she should receive more recognition (or other reward) than a group member who makes only a minor contribution to solving the problem. Rule 5: Find some constructive behavior to reinforce. This rule stems from behavior shaping, rewarding any response in the right direction and then rewarding only the closest approximation. Using this approach, the desired behavior is finally attained. Behavior shaping is useful to the manager because the technique recognizes that you have to begin somewhere in teaching a worker a new skill or motivating a worker to make a big change. For example, if you were attempting to motivate a group member to make exciting computer graphics (such as PowerPoint), you would congratulate the first step forward from preparing a mundane overhead transparency. You would then become more selective about what type of presentation received a reward. Rule 6: Schedule rewards intermittently. Rewards for good performance should not be given on every occasion. Intermittent rewards sustain desired behavior longer, and also slow the process of behavior fading away when it is not rewarded. If a person is rewarded for every instance of good performance, he or she is likely to keep up the level of performance until the reward comes, then slack off. Another problem is that a reward that is given continuously may lose its impact. A practical value of intermittent reinforcement is that it saves time. Few leaders have enough time to dispense rewards for every good deed forthcoming from team members. Rule 7: Ensure that rewards and punishments follow the behavior closely in time. For maximum effectiveness, people should be rewarded shortly after doing something right, and punished shortly after doing something wrong. A built-in feedback system, such as a computer program working or not working, capitalizes on this principle. Many effective leaders get in touch with people quickly to congratulate them on an outstanding accomplishment. Rule 8: Change the reward periodically. Rewards do not retain their effectiveness indefinitely. Team members lose interest in striving for a reward they have received many times in the past. This is particularly true of a repetitive statement such as “Nice job” or “Congratulations.” Plaques for outstanding performance also lose their motivational appeal after a group receives many of them. It is helpful for the leader or manager to formulate a list of feasible rewards and try different ones from time to time. Rule 9: Make the rewards visible and the punishments known. Another important characteristic of an effective reward is the extent to which it is visible, or noticeable to other employees. When other workers notice the reward, its impact multiplies because other people observe what kind of behavior is rewarded.[4] Assume that you are told about a coworker having received an exciting assignment because of high performance. You might strive to accomplish the same level of performance. Most people are aware that public punishments are poor human relations. Yet when coworkers become aware of what behaviors are punished, they receive an important message. A good example took place in a security systems office when a new member of the team distributed a series of sexually offensive jokes by email to coworkers. The man was immediately put on probation, and coworkers received a message about what constitutes unacceptable behavior. Research indicates that behavior modification leads to important outcomes such as productivity improvement. For example, an experiment was conducted in the operations division of a company that processes and mails credit card bills for several hundred financial institutions, ecommerce customers included. The four groups in the study were those receiving (1) routine pay for performance, (2) monetary incentives based on behavior mod, (3) social recognition, such as public compliments, and (4) performance feedback. Monetary rewards based on the principles of behavior modification outperformed routine pay for performance, with a performance increase of 37 percent versus 11 percent. Monetary incentives also had stronger effects on performance than social recognition and performance feedback.[5] Evidence like this is reassuring to the leader or manager who intends to apply behavior modification in the workplace. [1] Fred Luthans and Alexander D. Stajkovic, “Reinforce for Performance: The Need to Go Beyond Pay and Even Rewards,” Academy of Management Executive, May 1999, pp. 49, 56. [2] An update on some of the behavior modification rules is presented in Luthans and Stajkovic, “Reinforce for Performance,” pp. 49-57. [3] Fred Luthans, Organizational Behavior, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1992), p. 237. [4] Steven Kerr, Ultimate Rewards: What Really Motivates People to Achieve, (Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing, 1997). [5] Alexander D. Stajkovic and Fred Luthans, “Differential Effects of Incentive Motivators on Work Performance,” The Academy of Management Journal, June 2001, pp. 580-590.