2. revegetation - Main Roads Western Australia

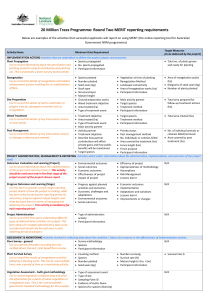

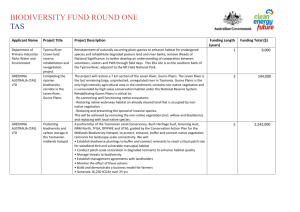

advertisement